Why innovate, and for whom?

We are being told that innovation and (green) growth are crucial to our economy, as well as to our prosperity. Just last week, the Sveriges Riksbank handed out the Nobel Prize for Economy to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt for their research on economic growth and innovation. In contrast, UG professor Klaus Hubacek envisions a world in which every human can flourish within the limits of this planet. He argues that economic growth is not the right benchmark, and we should seriously consider which innovations are desirable and for whom.

FSE Science Newsroom | Charlotte Vlek

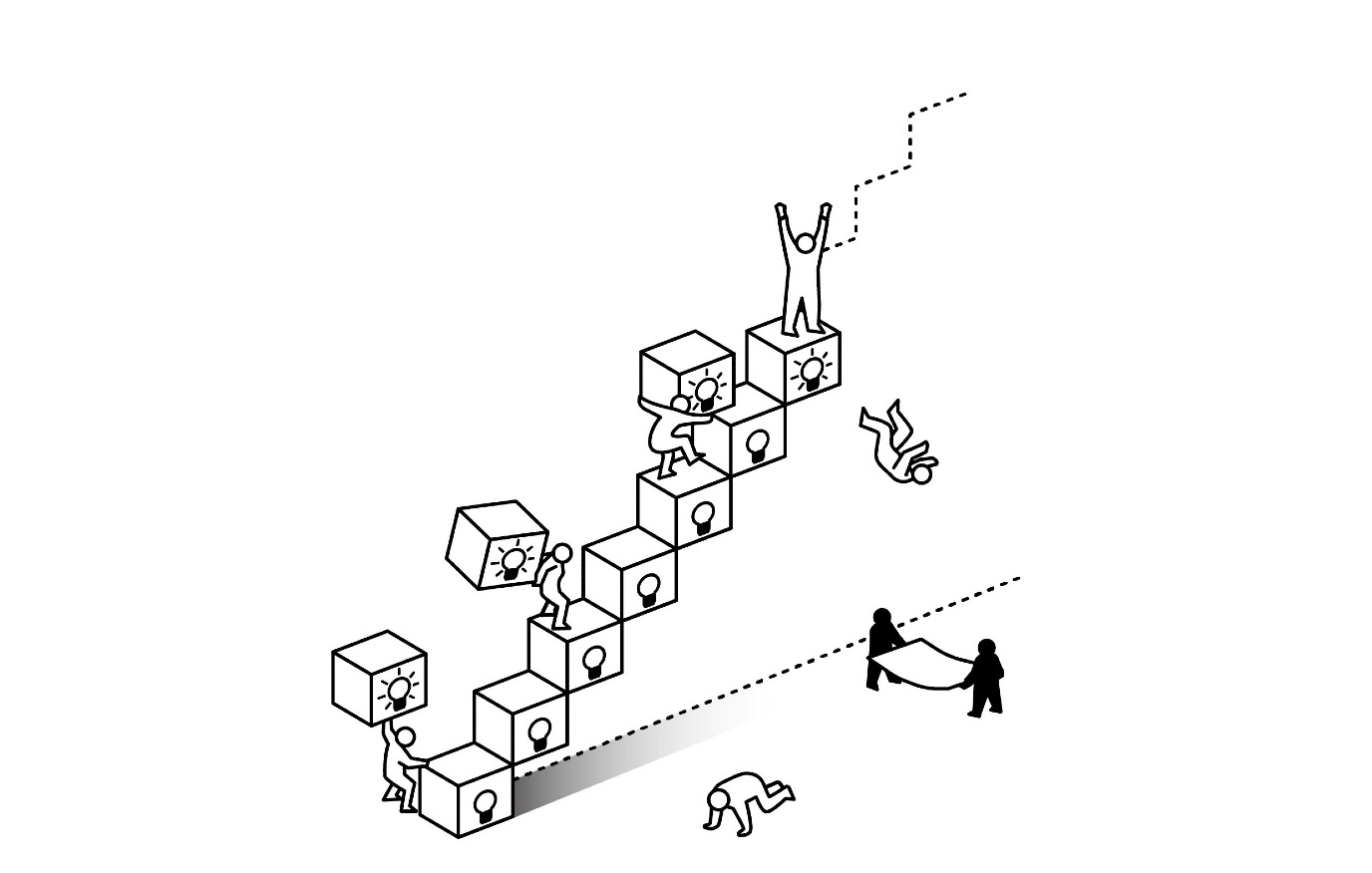

This raises fundamental questions about who will ultimately bear the burdens of creative destruction and who will reap its rewards

Creative destruction, that is the technical term for new innovations outcompeting older ones in a market economy. Think of the Walkman, the Discman, and the mp3-player, where the older technology largely disappeared as a new one emerged. According to Nobel Prize winners Mokyr, Aghion, and Howitt, the combination of innovation upon innovation and creative destruction leads to economic growth.

As Hubacek notes, however, ‘the benefits of such creative destruction tend to accrue to those with capital, skills, and purchasing power. This raises fundamental questions about who will ultimately bear the burdens of creative destruction and who will reap its rewards. The costs – such as environmental degradation, job displacement, and social disruption – often fall to vulnerable communities.’

Although a continuous train of new innovations may lead to economic growth, such growth does not necessarily result in favourable circumstances for those involved, be they people or ecosystems. ‘Environmental constraints even tend to fall disproportionally on the poorest, thereby compounding existing inequalities,’ observes Hubacek.

Mokyr has argued that social issues and damage to the environment may spark new waves of technological innovation and set a potentially self-correcting process in motion. According to Hubacek, however, this does not work out in practice: ‘New innovations frequently elicit rebound effects: efficiency improvements or new technologies often induce higher consumption, increasing resource use and generating additional environmental harm.’ For instance, all the wind and solar power that is now being generated has barely been able to keep pace with the ever-increasing global demand.

And what about green growth?

We need to ask deeper questions about the nature and purpose of innovation

Could green growth be a better option? Although green growth also revolves around technological progress, it aims to reduce the negative environmental impact of innovations. As Hubacek notes, however, ‘empirical evidence remains sobering. Global carbon emissions have continued to rise, and other environmental indicators are also not very hopeful – from biodiversity loss to material footprint. Only relatively few high-income economies are showing signs that economic growth and some environmental impact no longer go hand in hand. That would be an example of green growth. But this often comes with a degree of consumption that cannot serve as a role model for developing countries.’

Innovation as an aim in itself is not sufficient, Hubacek concludes. ‘We need to ask deeper questions about the nature and purpose of innovation. If technological change alone cannot guarantee equitable or ecologically viable outcomes, how can we steer it toward higher social returns and lower environmental costs? What institutional, political, and cultural barriers limit the adoption of truly transformative technologies that make the world a better place?’

How humans can flourish within ecological limits

Alternative economic paradigms – such as post-growth, degrowth, and wellbeing economics – offer valuable insights. Hubacek: ‘These approaches challenge the presumption that growth, even innovation-driven growth, is the primary measure of progress. Instead, they emphasize sufficiency and redistribution, such that all humans can flourish within ecological limits. The integration of such perspectives prompts us to ask not only what technologies we need, but how much technological expansion is desirable, and for whom.’

Read more:

Klaus Hubacek analyses the effects of various green solutions to reduce CO2 emissions — such as planting more trees, sharing cars, or working less — to find out whether they realize their intended outcome. Spoiler: almost everything has a downside, yes, even planting trees in some cases.

How much land, water, and other resources does our lifestyle require? And how can we adapt this lifestyle to stay within the limits of what the Earth can give?

The European Green Deal will bring the emission of greenhouse gases in the European Union down, but at the same time causes more than a twofold increase in emissions outside its borders.

Action to protect the planet against the impact of climate change will fall short unless we reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the global food system, which now make up a third of all man-made greenhouse gas emissions. These results are described in a paper by an international group of scientists led by the Universities of Groningen and Birmingham, which was published in Nature Food on 15 June.

Governments could help millions of people and save a lot of money with targeted energy subsidies. Different kinds of households around the world suffer in various ways from the exorbitant energy prices and need different kinds of support, states Klaus Hubacek from the University of Groningen in a new study that was published {today} in Nature Energy.

Thirty-eight Chinese cities have reduced their emissions of planet-warming carbon dioxide (CO2) despite growing economies and populations for at least five years. A further 21 cities have cut CO2 emissions as their economies or populations have ‘declined’ over the same period - defined as passively emission declined cities. This is revealed by new research from the Universities of Birmingham (UK), Groningen (Netherlands), and Tsinghua University (China).

If the UN Sustainable Development Goal to lift over one billion people out of poverty were to be reached in 2030, the impact on global carbon emissions would be minimal. That sounds good; however, the main reason for this is the huge inequality in the carbon footprint of rich and poor nations. This conclusion was drawn by scientists from the Energy and Sustainability Research Institute of the University of Groningen (the Netherlands), together with colleagues from China and the US.

More news

-

29 January 2026

Microplastic research - media hype or real danger?

-

27 January 2026

ERC Proof of Concept grant for Maria Loi