Why only a small number of planets are suitable for life

An international team of astronomers, including Dr. Rob Spaargaren from the University of Groningen, has demonstrated why only a small number of planets have the chemical requirements for life - and why the Earth is so fortunate. Their findings may have consequences for the search for life elsewhere in the universe.

FSE Science Newsroom | Text ETH Zürich

For life to develop on a planet, certain chemical elements are needed in sufficient quantities. Phosphorus and nitrogen are essential. Phosphorus is vital for the formation of DNA and RNA, which store and transmit genetic information, and for the energy balance of cells. Nitrogen is an essential component of proteins, which are needed for the formation, structure, and function of cells. Without these two elements, no life can develop out of lifeless matter.

A study led by Craig Walton, postdoc at the Centre for Origin and Prevalence of Life at ETH Zurich, and ETH professor Maria Schönbächler has now shown that there must be sufficient phosphorus and nitrogen present when a planet’s core is formed. ‘During the formation of a planet’s core, there needs to be exactly the right amount of oxygen present so that phosphorus and nitrogen can remain on the surface of the planet,’ explains Walton. This was exactly the case with the Earth around 4.6 billion years ago – a stroke of chemical good fortune. This finding may affect how scientists search for life elsewhere in the universe.

A form of cosmic roulette

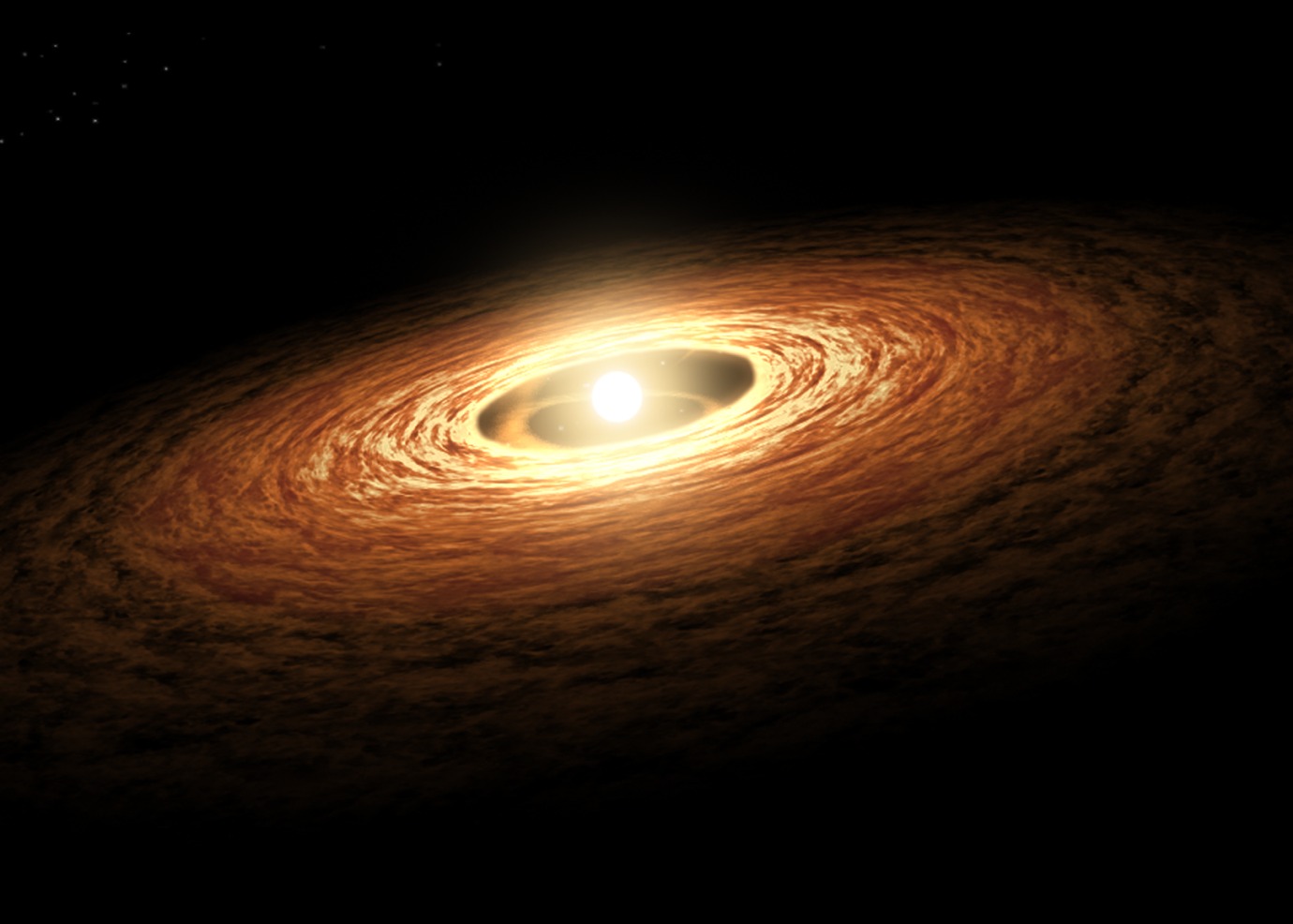

When planets form, they initially develop out of molten rock. A sorting process occurs during this time: heavy metals such as iron sink down and form the core, while lighter metals form the mantle and, later, the crust.

If there is too little oxygen present during the formation of the core, phosphorus will fuse with heavy metals such as iron and move to the core. This element is then no longer available for the development of life. On the other hand, too much oxygen present during core formation leads to phosphorus remaining in the mantle and nitrogen being more likely to escape into the atmosphere, ultimately being lost.

Chemical Goldilocks zone

Walton and his co-authors demonstrated through numerous modellings that only in an exceptionally narrow range of medium-level oxygen conditions – known as a chemical Goldilocks zone – will both phosphorus and nitrogen remain in the mantle in sufficient quantities. The Earth is precisely within this range.

The new findings could change how scientists look for life elsewhere in the universe. Until now, the focus has been predominantly on whether a planet possessed water. According to Walton and Schönbächler, this falls some way short.

The amount of oxygen available during a planet's formation can mean that many planets are chemically unsuitable for life from the very beginning, even if water is present and they otherwise appear to have the right conditions for life.

The search for similar solar systems

These chemical prerequisites for life can be measured indirectly by astronomers by observing other solar systems using large telescopes. The amount of oxygen present in a solar system for the formation of planets depends on the chemical composition of the host star. The star’s chemical structure shapes the entire planetary system around it, as planets are primarily composed of the same material as their host star.

Solar systems that differ significantly from our own in terms of their chemical composition are therefore not good places to look for life elsewhere in the universe. ‘This makes searching for life on other planets a lot more specific. We should look for solar systems with stars that resemble our own Sun,’ says Walton.

Reference: Walton CR, Rogers LK, Bonsor A, Spaargaren R, Shorttle O, Schönbächler M: The chemical habitability of Earth and rocky planets prescribed by core formation, Nature Astronomy, 9 February 2026

Read more:

In the search for extraterrestrial life, we generally look at planets that are more or less similar to Earth. Astrophysicists Inga Kamp and Floris van der Tak explain how the international LIFE-mission will search for life in new ways, and that planets that appear similar, might actually be composed of entirely different molecules.

More news

-

09 February 2026

Can we make the earth spin in the opposite direction?

-

29 January 2026

Microplastic research - media hype or real danger?