Stormy planets and an unexpected atmosphere

Once upon a time, it was quite special to find a new planet outside our own solar system. Nowadays, we know of over 6,000 of these exoplanets and sometimes we even know what kinds of climates these exoplanets have. Planetary scientist Quentin Changeat studies the atmosphere of hot Jupiter-like planets, while his colleague Tim Lichtenberg is excited to have found an atmosphere around a planet that, according to scientific consensus, was not supposed to have one.

FSE Science Newsroom |Text Charlotte Vlek | Visual editing Leoni von Ristok

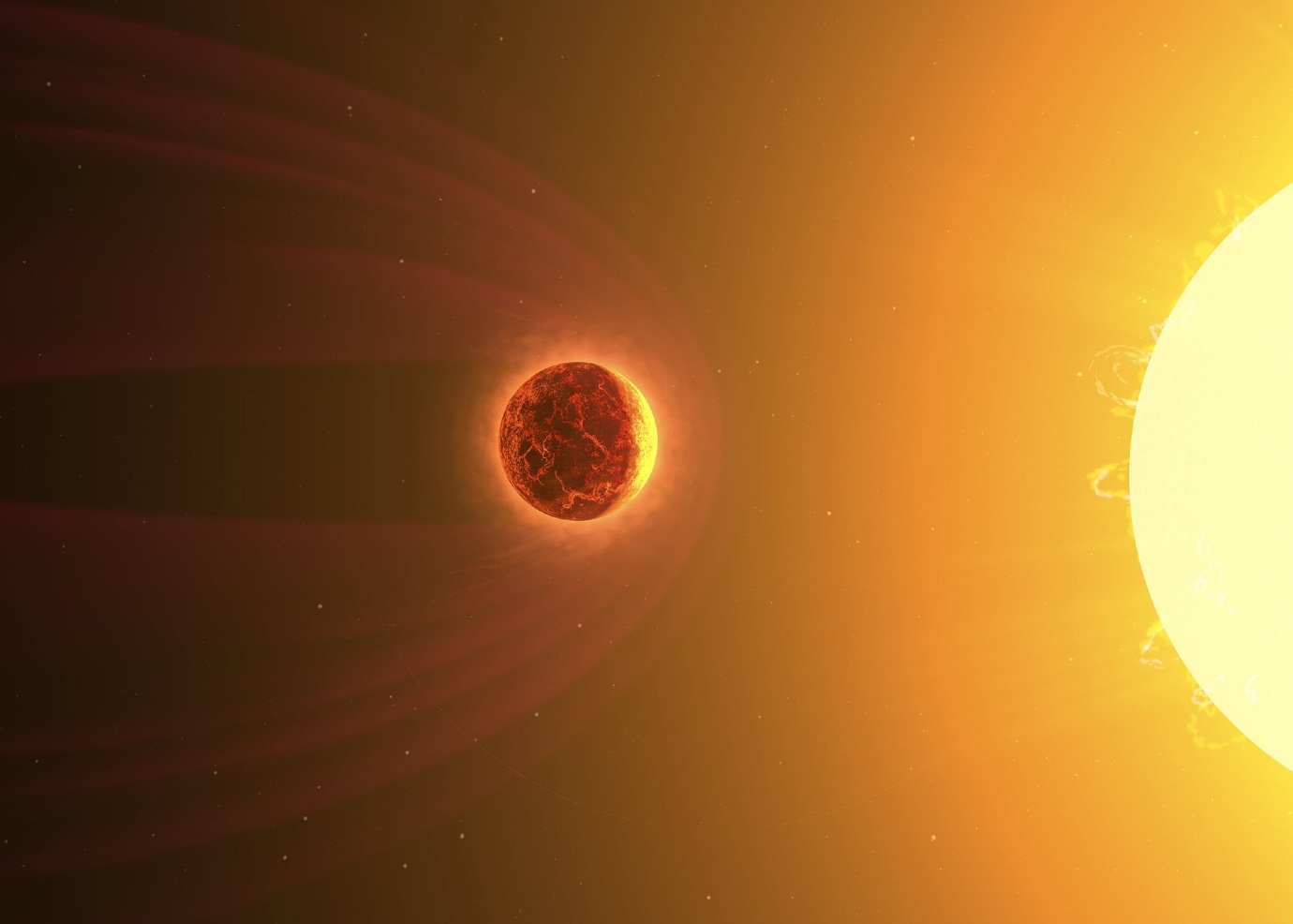

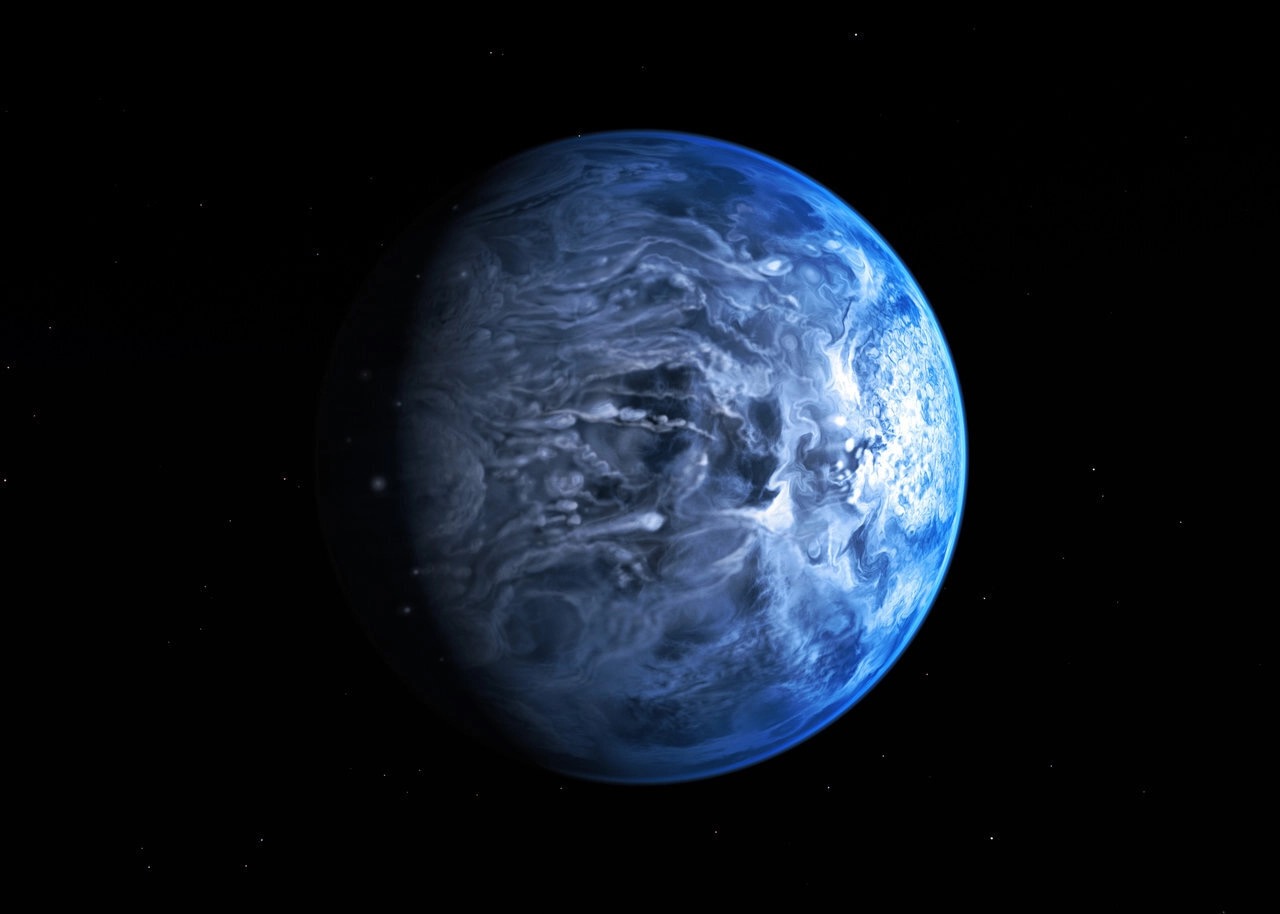

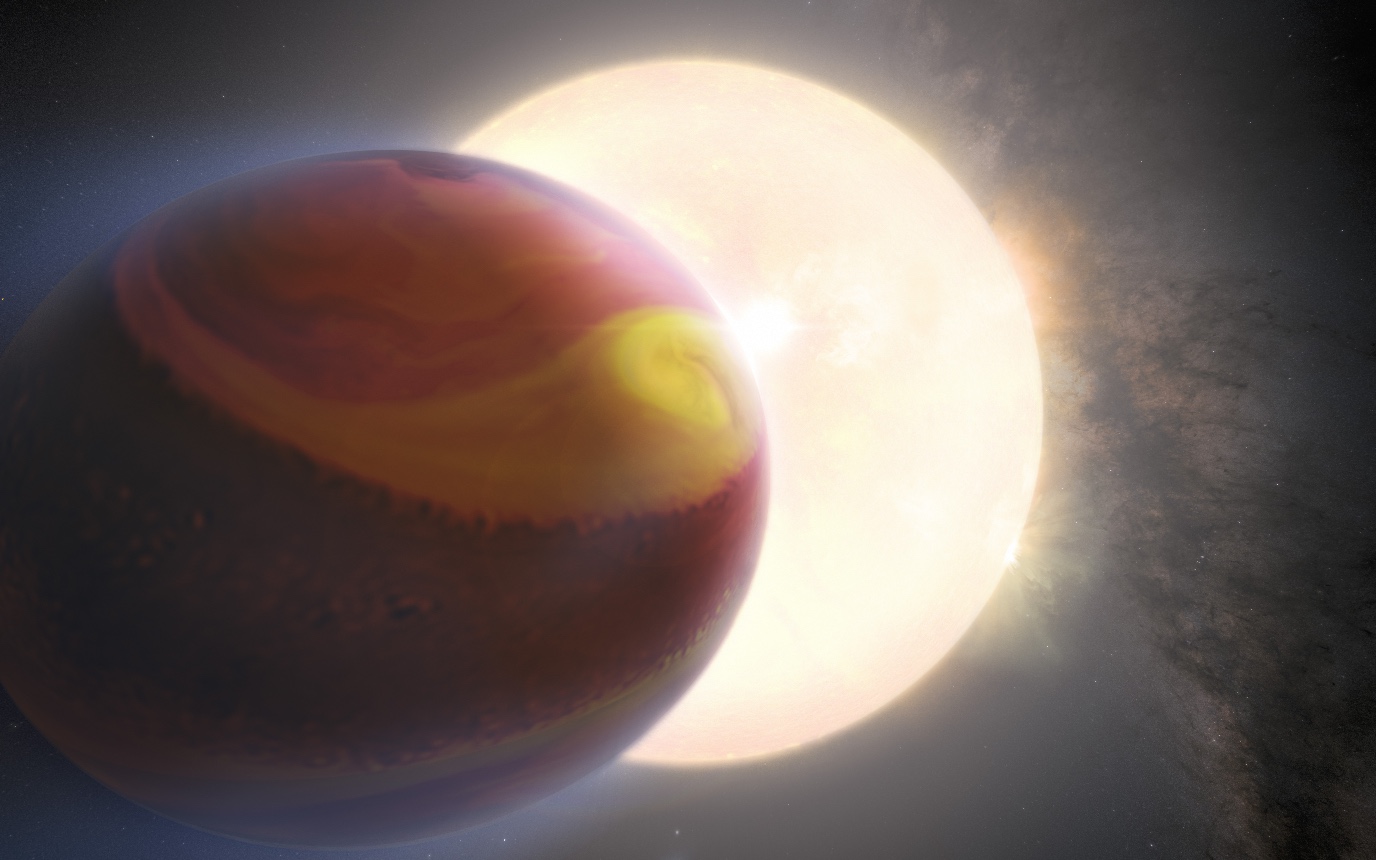

There are planets where it’s raining glass, or liquid iron. There are planets where it’s always day on one side, or where a year lasts only a few hours. Take WASP-121b, a giant planet that is made up of gases and that orbits its star very closely: one trip around the star lasts only 30 hours. It’s superhot, about 2500 degrees Celsius on the sunny side, while the other side still reaches about 1500 degrees.

Together with a team of international colleagues, Changeat studied the climate of WASP-121b and developed new methods to perform calculations on such extreme climate patterns. ‘They revealed that there must be heavy storms on this planet,’ Changeat reports. Earlier, he investigated the composition of 25 Jupiter-like gas giants and he is currently working out the plans for a new research programme that will analyse the atmospheres of another 1,000 exoplanets.

‘I mostly study large, hot planets,’ Changeat explains, ‘because these give us the clearest signals.’ You can ‘see’ an exoplanet by noticing that the planet blocks the light from a star when it passes in front of it–as seen from Earth. And a larger planet takes away more light than a smaller planet. Furthermore, Changeat and his colleagues can infer the composition of the atmosphere from the colours that are filtered through: every molecule has its own ‘fingerprint’ in the light spectrum.

Are we looking at exoplanets to find extra-terrestrial life?

‘There have been multiple claims of finding life on exoplanets, but they are all very controversial,’ Lichtenberg reports. When reading about exoplanets in the news, you might think that it is all about the search for extra-terrestrial life. But that is not what motivates Changeat and Lichtenberg. Both are looking at exoplanets mainly to better understand Earth and our own solar system.

Changeat: ‘There are so many questions about our own solar system. Why is Mars so dry? Why do we have such a large planet like Jupiter? Why is our Moon so large? Scientists have developed theories to answer these questions, but they all turn out to have their limitations when looking at exoplanets.’

‘My main motivation is that I want to find out how life could have arisen at Earth,’ Lichtenberg explains. To that end, he also makes simulations that calculate how planets form and how they develop their climate. Informed by all this knowledge about exoplanets, this in turn teaches us something about how Earth may have formed. Lichtenberg: ‘And about the circumstances in which life could have developed on this planet.’

An unexpected atmosphere

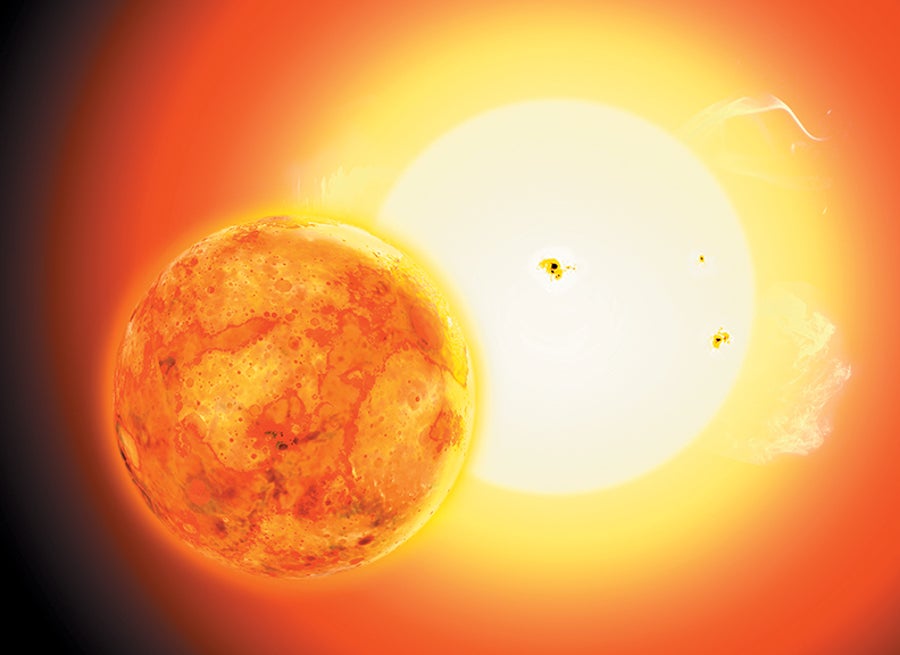

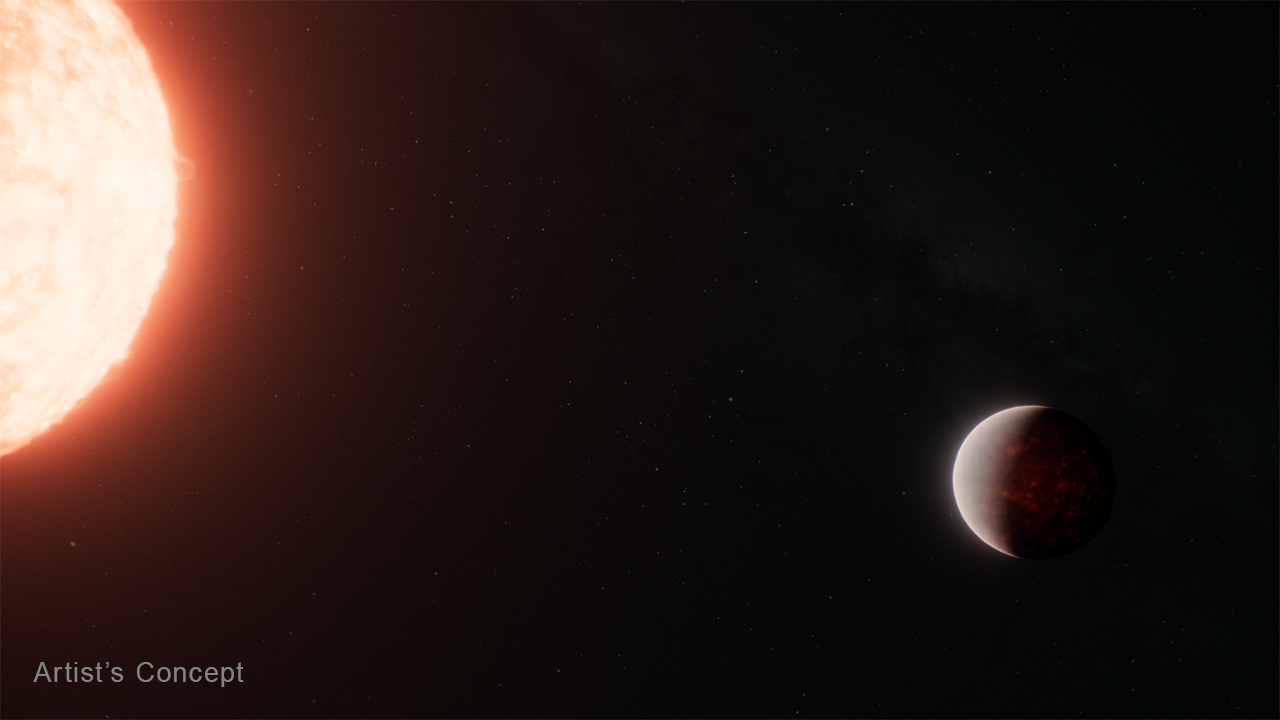

Lichtenberg is interested in rocky planets of a size comparable to the size of Earth. Lichtenberg: ‘Planets of a similar size are often orbiting a relatively small star–at least those that we are able to detect at present. The orbits of these known exoplanets are usually extremely close to their star. Typically, we would expect that if there were an atmosphere, it would have been blown away. Nonetheless, Lichtenberg and his colleagues discovered that the exoplanet TOI-561 b must have an atmosphere, even though it is mostly a hot lava ball that completes its orbit in just 11 hours.

About Earth-like planets and Sun-like stars

Earth is a rather small, rocky planet. It is much easier to detect other planets of this size when they orbit a relatively small star–much smaller than our own Sun. Because if you want to detect a small planet near a large star, it is a bit like finding a tiny moth near a floodlight: the moth takes away so little light from the enormous light source behind it, that you would hardly notice.

In contrast, a small planet near a small star is perceivable and that is why we mostly know about Earth-like planets near M-dwarf stars. Lichtenberg: ‘We’d like to find an Earth-like planet near a Sun-like star, but we don’t really have the tools to do it right now. Perhaps next year, when the PLATO mission starts. But even then, you would only be able to detect the planet and measure its size, without being able to obtain more details about its climate.’

Theoretical models designed by Lichtenberg show that the atmosphere of such planets can continue to exist due to a fine balance in which gases from the inside of the planet feed the atmosphere, while elsewhere the atmosphere is being sucked into the hot lava surface of the planet. ‘You could compare the effect to a coke can from which gas escapes when you open it, but reversed,’ Lichtenberg explains. ‘Instead of gas escaping, like with a coke can, the gas is being sucked into the magma, which shields the gas from escaping into space.’ With this finding, Lichtenberg and colleagues show how the climate of a planet is not only related to its atmosphere, but also to a planet’s interior.

Today, there was also a press release about the atmosphere around exoplanet TOI-561 b, decribed by Tim Lichtenberg and colleagues. And last week, visiting professor Laura Kreidberg of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg gave the yearly Blaauw lecture, this year with the theme of exoplanets. She is working with the James Webb Space Telescope on the observation of rocky planets.

Read more:

In the search for extraterrestrial life, we generally look at planets that are more or less similar to Earth. Astrophysicists Inga Kamp and Floris van der Tak explain how the international LIFE-mission will search for life in new ways, and that planets that appear similar, might actually be composed of entirely different molecules.

More news

-

29 January 2026

Microplastic research - media hype or real danger?

-

27 January 2026

ERC Proof of Concept grant for Maria Loi