What makes for healthy soil?

Healthy soil does not need chemical fertilizers, is more resilient against pests and diseases, and can take up more water and carbon. But what exactly constitutes healthy soil, and how do we bring it back once it has deteriorated? This is what Professor of Microbiology Joana Falcao Salles and postdoc Barbara Prack McCormick are studying.

FSE Science Newsroom | Text Charlotte Vlek | Images Leoni von Ristok

This is the first in a three-part series about sustainable agriculture research at the Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Groningen. Today’s topic is healthy soil; in the next two articles, you can read more about how plants adapt to a changing environment and how we can help animals that suffer from our intensive use of land.

Plants and soil can feed each other in an ingenious collaboration: a plant captures energy from sunlight and carbon dioxide (CO2) and shares a substantial part of that energy with the soil through its roots. ‘It’s a bit like the roots of the plant are sweating,’ Prack McCormick explains. The official term for this ‘sweat’ is exudates, and through these exudates bacteria and fungi are attracted, which in turn help the plant. For instance, bacteria can produce hormones that promote plant growth or fix nitrogen in the soil. And when bacteria and fungi are eaten by larger soil life such as nematodes (tiny worms), their remains form nutrients for the plant.

We humans are messing it up

‘But we humans are messing it up!’ Falcao Salles explains. All kinds of beneficial functions that healthy soil can serve – not just nutrients for plants, but also regulating pests and diseases and building a good soil structure – are organized in artificial ways in regular agriculture. Chemical fertilizers make it redundant for plants to produce exudates and for bacteria to fix nitrogen, so they stop doing it. Pesticides disrupt the regulating functions of larger soil life, and tillage grinds worms and fungi to pieces. Consequently, we lose all kinds of useful functions, because healthy soil can hold much more rainwater and store more carbon.

Listening to soil

Science LinX, the Science Centre of the Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, tagged along on a visit of the researchers to a farm in Drenthe. With the use of soil microphones, they listened to the creatures living below ground. The difference between different types of grassland was clear to those present at the farm: herb-rich grassland with high grass, grazed by cows, exhibited much more sounds than the short, machine mown grass elswhere.

Learn more about listening to soil in the podcast Groninger Grond (in Dutch).

How can soil be restored?

So, it is time to give the soil a chance to recover. ‘Suppose you’ve got a field,’ Falcao Salles describes. ‘Perhaps it’s been used in the past for intensive agriculture, with fertilizer, pesticides, and tillage. What is needed to restore the soil?’ There are already some solid principles from agroecology and regenerative agriculture, and Falcao Salles and Prack McCormick measure their effect on the soil, working with farmers who are putting these principles into practice.

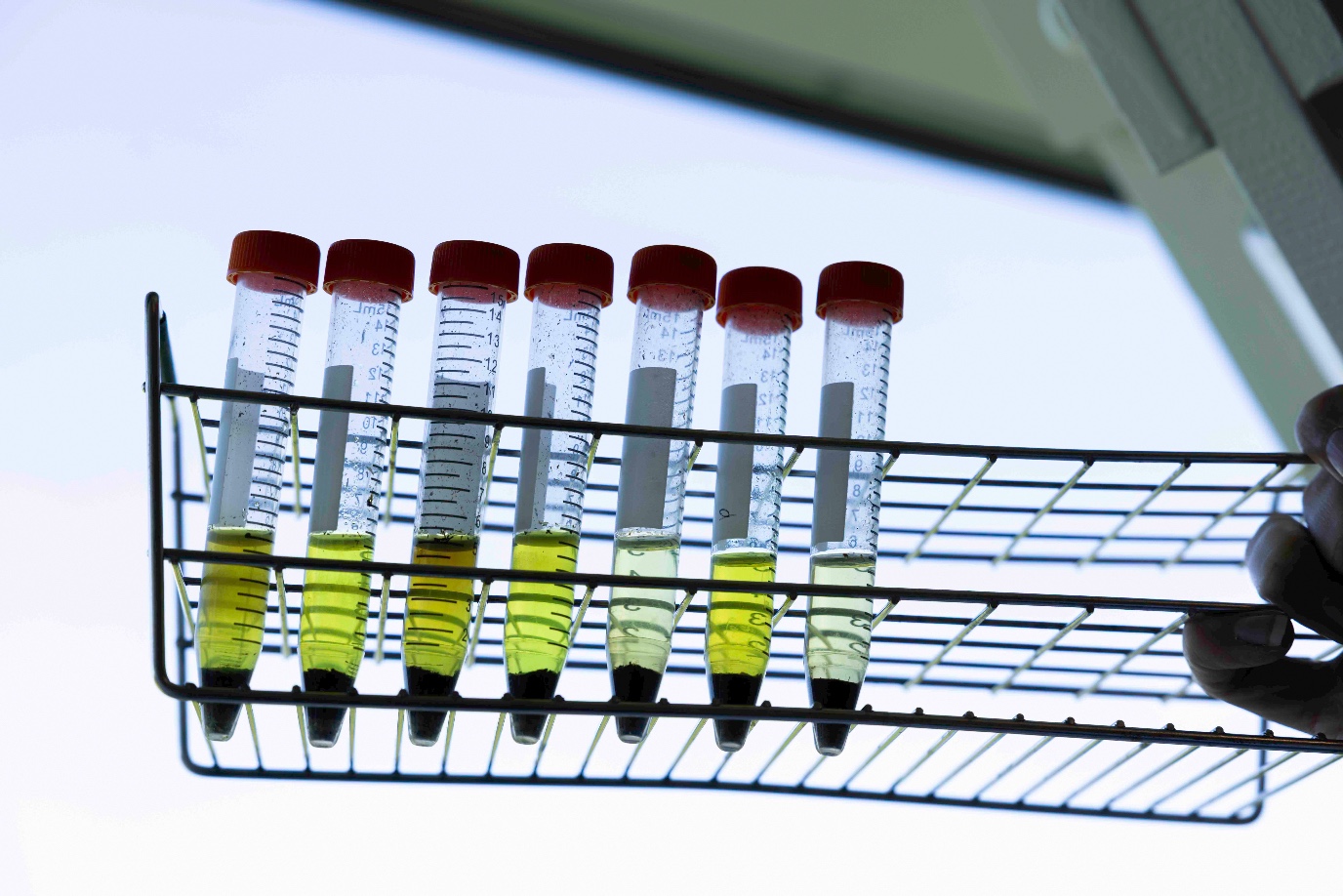

Prack McCormick: ‘We collect soil samples, take them back to the lab with some ice packs, and look at the composition.’ She measures the compaction of the soil, the amount of carbon it has stored, which micro-organisms are there, and which enzymes these micro-organisms produce that enable the nutrient cycle, resulting in nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulphur.

Compaction sometimes never recovers

Prack McCormick has conducted her analyses at various locations, ranging from grass fields to former arable land that has been converted into more biodiverse fields. In some cases, this transition happened ten years ago, and in others, twenty or thirty years ago. This enables the researcher to see how land recovers through time: ‘We see that enzymes that facilitate nutrient cycling recover rather quickly. The ability to store carbon takes much longer, and the compaction of arable land sometimes doesn’t recover at all.’

Indicators of healthy soil

Both Falcao Salles and Prack McCormick are looking for indicators that can give a somewhat quick answer to the question: is this healthy soil? Falcao Salles: ‘But there are so many micro-organisms, sometimes up to 50,000 species in a handful of soil.’ With the help of AI, she hopes to gain insight into which micro-organisms are truly essential. She focuses on three measurements: the nutrients in the soil, the enzymes that produce these nutrients, and the microbes. ‘So, we measure the current state of the soil, its functions, and the mechanisms behind it. And we try to find connections between these three.’

Recovery takes time

The next step is not only to measure how healthy the soil is, but also to find out which principles from agroecology and regenerative agriculture are best for soil restoration. ‘Perhaps this way we can help speed up the recovery process,’ Falcao Salles concludes. Recovering soil takes time. The two researchers saw at a farm in Drenthe that it can take about ten years. Falcao Salles: ‘At first, it seems to go quite well right after the transition, but that’s because the soil still has all these artificial nutrients. Then a decline follows, after which the soil gradually recovers itself.’

One thing the Dutch government could already stimulate, according to Falcao Salles, is not leaving fields uncovered in winter. ‘A field that is completely empty after harvesting has nothing to feed the microbes in the soil. It also goes through more extreme temperature fluctuations and can easily erode with heavy rain. But it’s relatively easy to leave the remains of plants, or better yet, to plant some green manure: plants that add useful nutrients to the soil for the next crop.’

Farmers only grow a limited number of crops these days, which has significant consequences for the animals that live there. Raymond Klaassen researches what adjustments farmers could make to improve the conditions for the species most affected by modern agriculture, such as the skylark.

Kira Tiedge investigates the chemical substances that plants use to communicate with their environment, to select robust varieties that can better withstand challenging circumstances such as diseases or drought.

More news

-

29 January 2026

Microplastic research - media hype or real danger?

-

27 January 2026

ERC Proof of Concept grant for Maria Loi