The carbon cycle as Earth’s thermostat

In an ingenious cycle, carbon is exchanged between atmosphere and oceans, plants, and rocks. However, this cycle becomes unbalanced if we, humans, continue to release extra carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere. In this overview article about the carbon cycle, you can find out how Earth generally keeps itself in balance and how we, humans, have upset this balance over the past two hundred years.

FSE Science Newsroom | Text Charlotte Vlek | Images Leoni von Ristok

Life on Earth is impossible without carbon. It is an essential building block for plants and animals, for humans and mosquitoes. When carbon ends up in the atmosphere in the form of CO2, it acts as a greenhouse gas, and we cannot do without that either: without greenhouse gases, Earth would be a cold ball of ice. However, if the atmosphere were to have extremely high levels of CO2, it could get as hot as it is on Venus, which is approximately 400 degrees Celsius. It is, therefore, a good thing that carbon circulates in an ingenious exchange between atmosphere, oceans, plants, and rocks: the carbon cycle.

Rocks and water, plants, and atmosphere

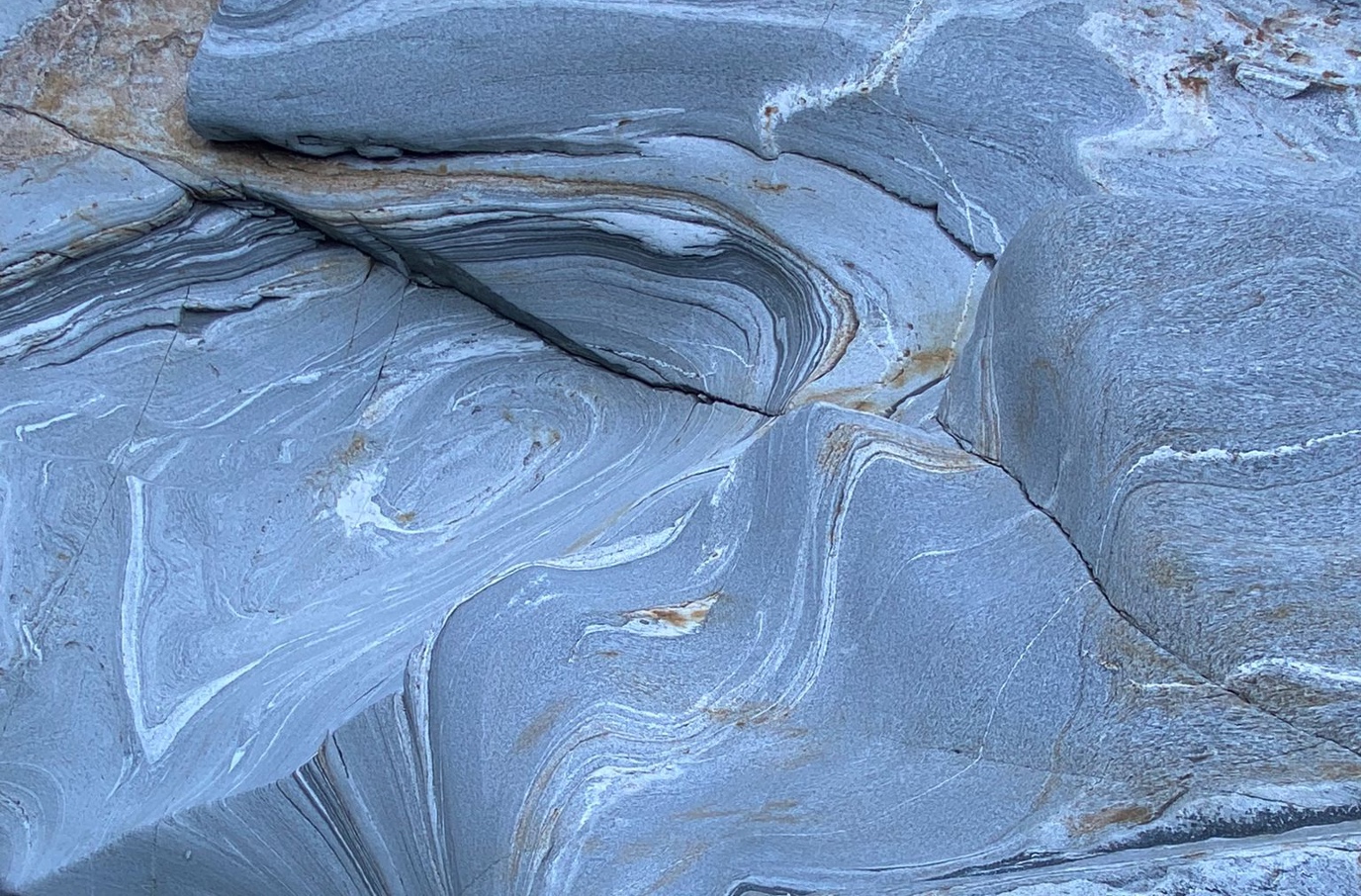

There is a fast and a slow carbon cycle. In the slow cycle, limestone is slowly worn away by rain, after which the dissolved carbon flows along with the water towards the sea. There, organisms such as phytoplankton absorb the carbon, and when these organisms die, they sink to the bottom of the sea where their remains once again form limestone. Carbon that has disappeared into the depths of the sea in this way sometimes comes up again through volcanic eruptions, after which the rain carries it along again.

In the fast carbon cycle, trees and plants absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, and after they die, the carbon ends up in the soil or back in the atmosphere. This resembles a type of ‘breathing’ that moves with the seasons: slightly lower CO2 concentrations in spring and summer (in the Northern hemisphere) and higher CO2 concentrations in autumn and winter. Furthermore, land and oceans also exchange CO2 with the atmosphere, keeping each other in balance.

Through measurements of the atmosphere, Harro Meijer is mapping the carbon cycle: what are the sources of CO2 and how much of it is absorbed by plants or oceans? He is studying this by looking at various forms of the carbon atom in the CO2.

Earth’s thermostat

The circulation of carbon leads to a balance in which the atmospheric CO2 concentration is roughly constant. This is how Earth regulates its own temperature, like a thermostat. However, sometimes the thermostat goes haywire: when Earth warms up a few degrees, it causes effects that warm it up even more. For example, peat fires on the Siberian tundra that were exposed due to the melting of the permafrost. Large quantities of carbon that were stored in these peatlands ended up as CO2 in the atmosphere, leading to Earth warming up even more.

Not all of the thermostat’s effects are self-reinforcing though. Ocean researchers Richard Bintanja and Rob Middag are studying the effects of melting glaciers and melting sea ice, thinking that this may lead to more phytoplankton in the polar seas and, consequently, more absorption of carbon into the sea water. This could then cool down the Earth to some extent.

The destructive effects of human emissions

By burning fossil fuels, we release extra carbon into the atmosphere in the form of CO2, carbon that would otherwise have stayed deep underground for a very long time. And due to our intensive use of land, for example for agriculture, there is less space for trees that could absorb that CO2 from the atmosphere and store it in their wood and in the soil.

Although the annual human CO2 emissions are relatively small compared to the entire cycle, they accumulate over the years, leading to destructive effects on the planet. In the final part of our series about the carbon cycle, ecological economist Klaus Hubacek explains what we can do to reduce our emissions—and also which green intentions are in fact a bit pointless.

Read more:

Klaus Hubacek analyses the effects of various green solutions to reduce CO2 emissions — such as planting more trees, sharing cars, or working less — to find out whether they realize their intended outcome. Spoiler: almost everything has a downside, yes, even planting trees in some cases.

‘Fortunately, seawater absorbs carbon dioxide (CO₂). If it didn’t, things would have been over and done with already,’ according to climate and ocean researchers Richard Bintanja and Rob Middag. But what actually happens to the ocean's carbon absorption as the climate changes?

In the year 2000, Harro Meijer, Professor of Isotope Physics at the University of Groningen, set up the Lutjewad Measurement Station near Hornhuizen. There, researchers from Groningen are mapping where CO2 in the atmosphere originates and where it ends up.

More news

-

10 February 2026

Why only a small number of planets are suitable for life

-

09 February 2026

Can we make the earth spin in the opposite direction?