The long search for new physics

In the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) near Geneva, Switzerland, millions of protons can collide every second at almost the speed of light. These collisions allow particle physicists to study the fundamental building blocks of matter, called quarks and leptons. Assistant professors Kristof De Bruyn and Ann-Kathrin Perrevoort from the University of Groningen use these collisions to discover unexplained phenomena that would point to new physics.

For over fifty years, physicists have used the Standard Model of particle physics to describe the building blocks of matter, and have even successfully predicted the existence of previously undiscovered particles, such as the Higgs boson. It does so very accurately, but despite its success, most physicists agree that the Standard Model does not tell the full story.

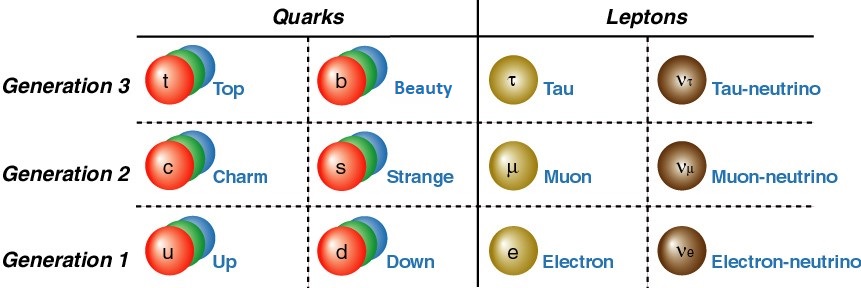

For instance, quarks (elementary particles) are grouped into two categories, called ‘up-type’ and ‘down-type’, each consisting of three ‘generations’. The down-type quarks are called down, strange, and beauty. Down is the lightest, beauty the heaviest. ‘However, we do not know why there are three generations, and not more than three or less than three,’ says Perrevoort. The same goes for the leptons, a group of twelve elementary particles that includes electrons and neutrinos. These also divide into two types and three generations. ‘We cannot yet explain these numbers.’

Speed of light

This is just one question that suggests our knowledge of matter is incomplete. That is why Perrevoort, De Bruyn, and most other particle physicists are convinced there must be physics beyond the Standard Model. To test the limits of the Standard Model, physicists design experiments that explore all kinds of effects as predicted — or forbidden — by the model.

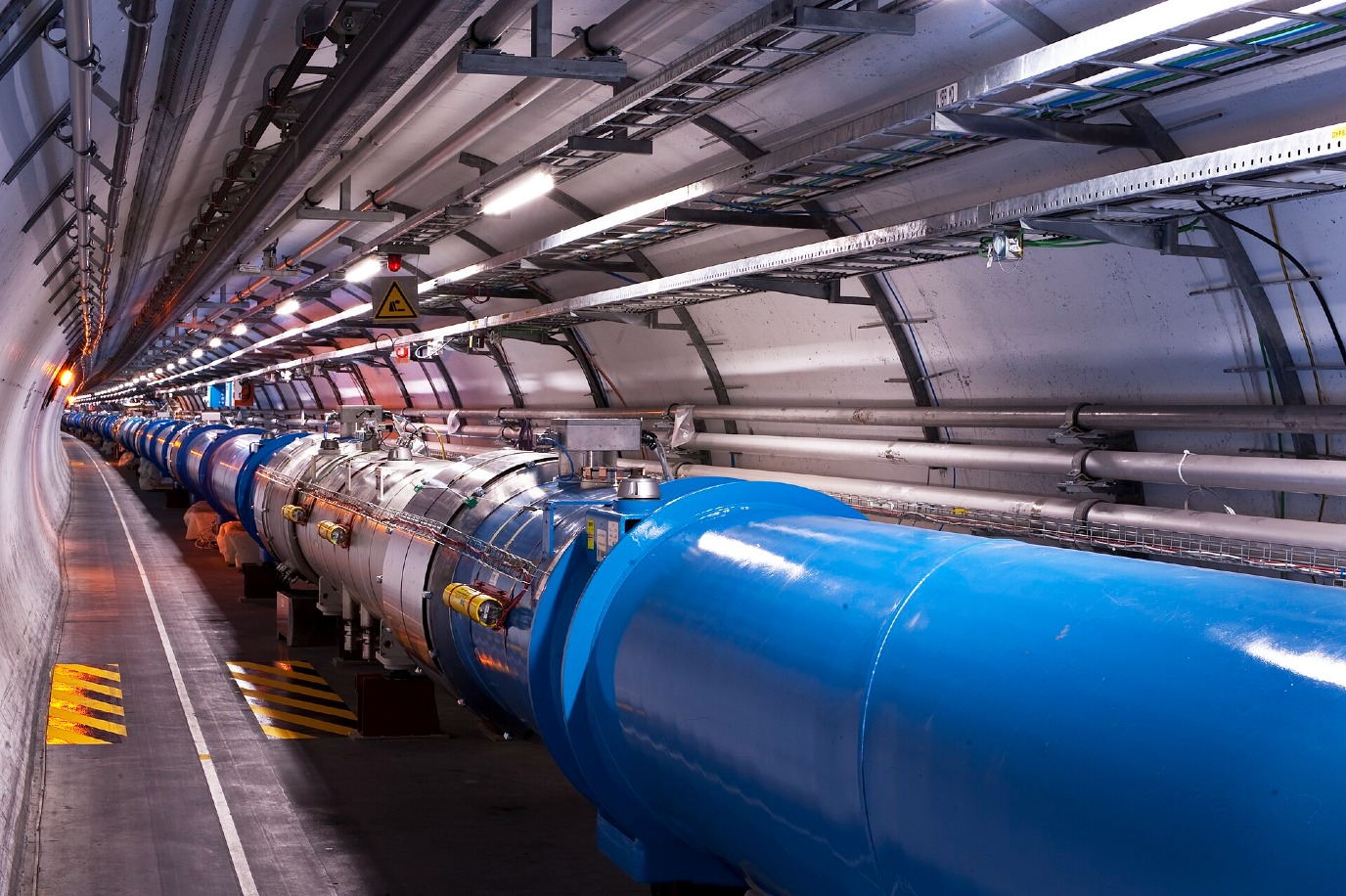

De Bruyn and Perrevoort, along with almost 10,000 other scientists, do this at the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator: the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), operated by the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN). The LHC is a circular tube with a 27-kilometre circumference, some 90 meters deep underground, in which protons are pushed to velocities near the speed of light, which gives them an extremely large amount of energy, and then makes them crash into each other head on.

Experiments at the LHC

At the Large Hadron Collider, nine different experiments are carried out. These experiments measure the results of proton-proton collisions, which occur at four points in the 27-kilometre circular accelerator. On these four ‘crash sites’, detectors are positioned to measure specific aspects of the collisions.

One of these experiments is LHCb, where the ‘b’ stands for the beauty quark, which is its object of study. This is the experiment in which Perrevoort, De Bruyn, and some 1,200 colleagues are involved. A full list of the experiments can be found on the CERN website.

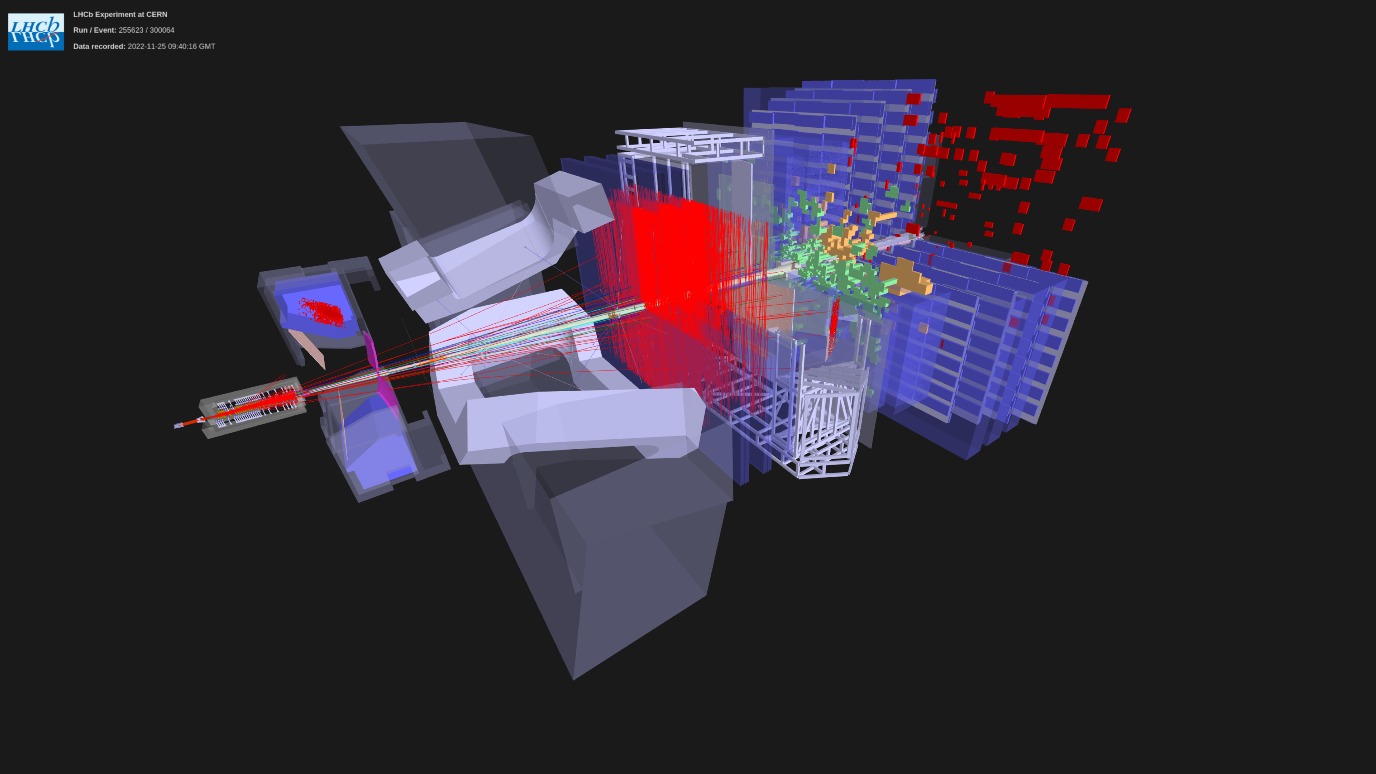

The result of such a crash is, according to De Bruyn, ‘like shooting two full garbage cans at each other.’ In the particle accelerator, instead of garbage, subatomic particles fly off in all directions. At the crash site, a huge detector registers the particles that contain a very heavy beauty quark, one of the six different types of quarks. This has given the experiment its name, LHCb(eauty). However, particles containing these quarks are very unstable, and they decay in a matter of picoseconds (a millionth of a millionth of a second) into other particles. A huge detector registers the products of this decay.

Information overload

Studying particles sounds fairly straightforward, until you hear the numbers involved. When the LHC operates, there are some 40 million proton-proton collisions per second. These have to be observed and analysed in real time, because the detectors monitoring the collisions produce too much information to store. The real time analysis, made by the VELO detector, looks for the ‘signature’ of a beauty quark among those millions of collisions. If this signature is present, the event is stored and then further analysed.

Perrevoort: ‘In the LHC, we can produce a large number of beauty quarks and study their decay in detail. This means we can test the predictions: if we find even the tiniest deviation, this could point us to physics beyond the Standard Model’. She looks for decay signals that are ruled out in the Standard Model but predicted by extensions to the model developed by theoretical physicists. ‘If we find those, this will point the way to new physics.’

Ruling out different paths

De Bruyn uses a different approach: ‘There are over 250 different ways in which a beauty quark can decay into other particles,’ he explains. For a number of those decay paths, theoretical physicists have been able to very accurately predict how this happens. ‘So, by measuring these particular paths, and comparing our experimental results to the predictions, we can test whether the theory is correct.’ Again, if the experiment produces results that the theory didn’t predict, it may reveal physics beyond the Standard Model.

Looking for beauty

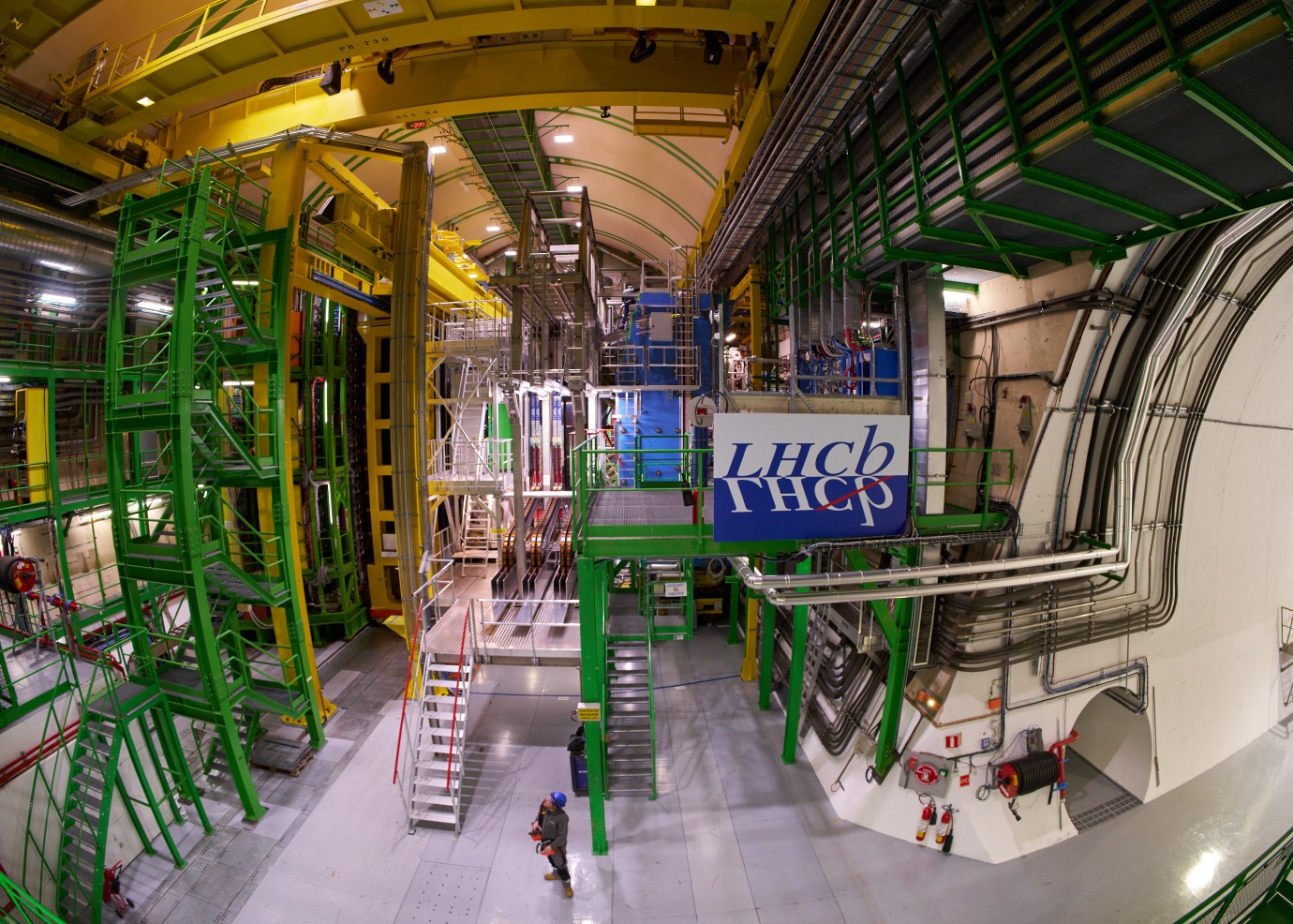

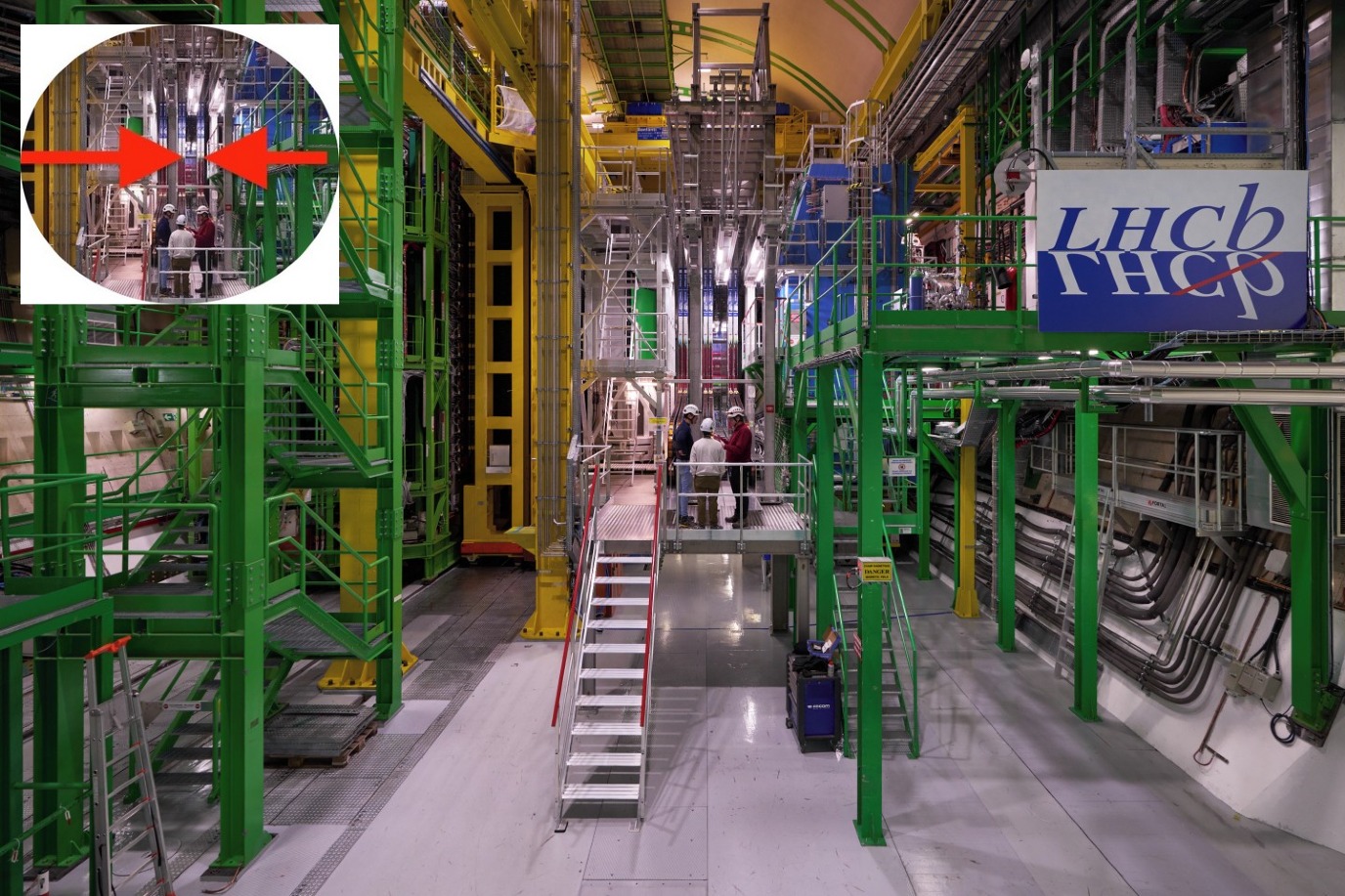

The LHCb experiment consists of a cavern-sized detector that is 20 metres long and 5 metres high. It has a unique design among the LHC experiments. Only the very forward direction is instrumented, as the particles containing beauty quarks are just produced there. Between the two arrows, the tube through which the protons flow is visible. The LHC's proton-proton collisions take place at a location inside the cavern wall at the right side in the picture. Surrounding this interaction point is the Vertex Locator, or VELO, which plays a crucial role in identifying particles containing beauty quarks. The team at the Van Swinderen Institute also contributes to the operation of the VELO and the development of its future upgrade.

The LHCb experiment started to produce and analyse beauty quarks in 2010. So far, no unambiguous sign for physics beyond the Standard Model has been found. Isn’t that disheartening? Perrevoort: ‘By ruling out different paths, we get a more detailed knowledge of the Standard Model, which means that we can rule out some ideas. Moreover, the measurements have already revealed some observations that are in tension with the Standard Model.’ These observations have not reached statistical significance, so more data and more precise measurements are needed. ‘But it does encourage the search for new physics.’

New physics

De Bruyn: ‘We also learn a lot on the way. It took around twenty years to build the detectors and perform the experiment, and we have made them incredibly precise. We are now redesigning the detectors for an upgrade that will be implemented in ten years.’ And later this year, the LHC will enter a ‘Long Shutdown’ of four years to carry out maintenance and to install upgrades that were developed in the past decade. This does not mean that the research is on hold. ‘Not at all,’ Perrevoort comments. ‘In recent years, we haven’t been able to process data into scientific papers at the rates the data is produced. The upcoming shutdown for the upgrade gives us time to catch up.’ And maybe, somewhere in this backlog of data, new physics is waiting to be discovered.

Frontiers in physics at the Van Swinderen Institute

Scientists at the Van Swinderen Institute for Particle Physics and Gravity study the fundamental forces of nature, the building blocks of matter, and how these are related to our Universe as a whole. This is divided into three research programs:

At the High-Energy Frontier, the focus is on elementary particle physics and high-energy collision experiments, all aimed at improving our understanding of the Standard Model of elementary particles and to find out what lies beyond.

At the Precision Frontier, the focus is on tabletop precision experiments with the aim of advancing our knowledge of particle physics by performing low-energy, extremely high precision experiments using cold atoms and molecules.

For the Cosmic Frontier, the aim is to connect fundamental physics theory to cosmological observations with the objective of understanding the physics of the early Universe, its inflationary period, and the imprint this has made in the Cosmic Microwave Background and in the gravitational wave spectrum, which can both be observed in the present.

More news

-

10 February 2026

Why only a small number of planets are suitable for life

-

09 February 2026

Can we make the earth spin in the opposite direction?