The search for extraterrestrial life — and can we broaden our ideas about it?

In the search for extraterrestrial life, we generally look at planets that are more or less similar to Earth. This week, 19–23 January 2026, astronomers from all over the world are coming to Groningen to talk about this type of rocky planets at the Rocky Worlds 4 conference. ‘But it is possible that some of these rocky planets and their atmospheres are very different from Earth,’ say Inga Kamp and Floris van der Tak, astrophysicists at the University of Groningen. For example, Kamp discovered that the gas and dust rings in which planets form near small stars — which are the most numerous in the Milky Way — are composed of entirely different molecules.

FSE Science Newsroom | Text Charlotte Vlek |Visual editing Leoni von Ristok

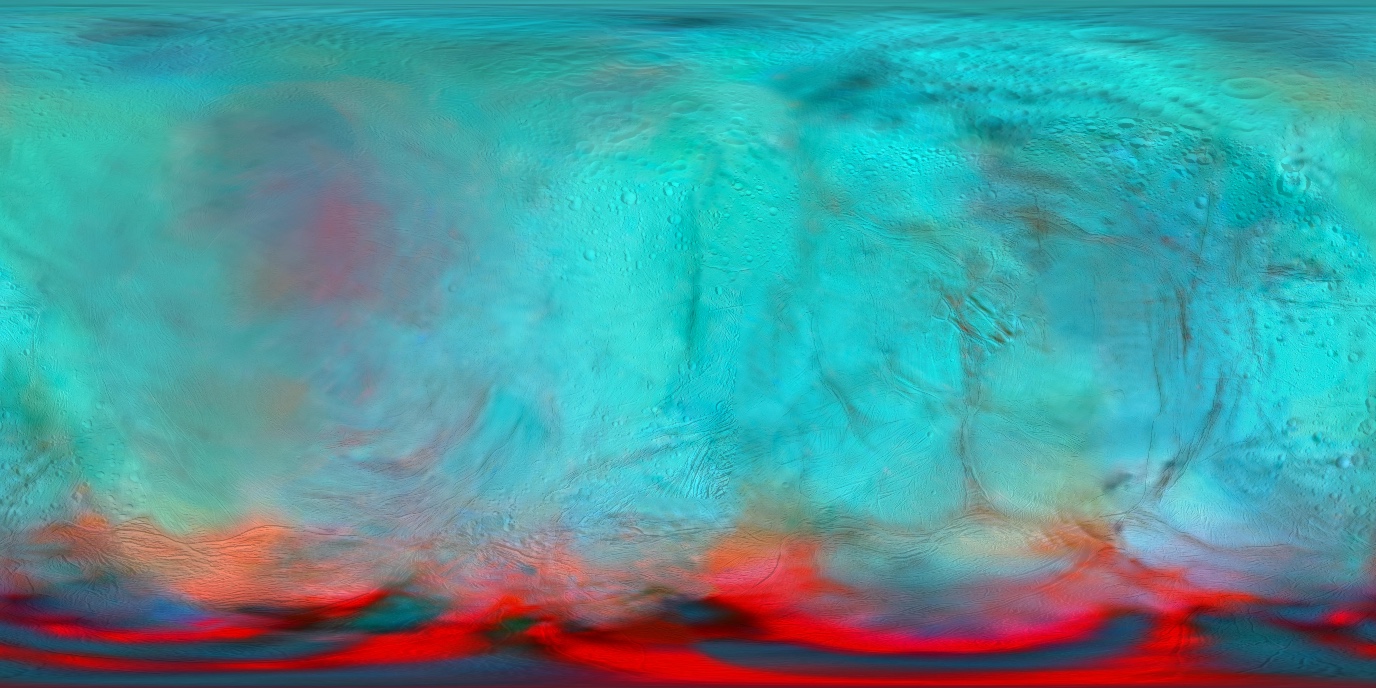

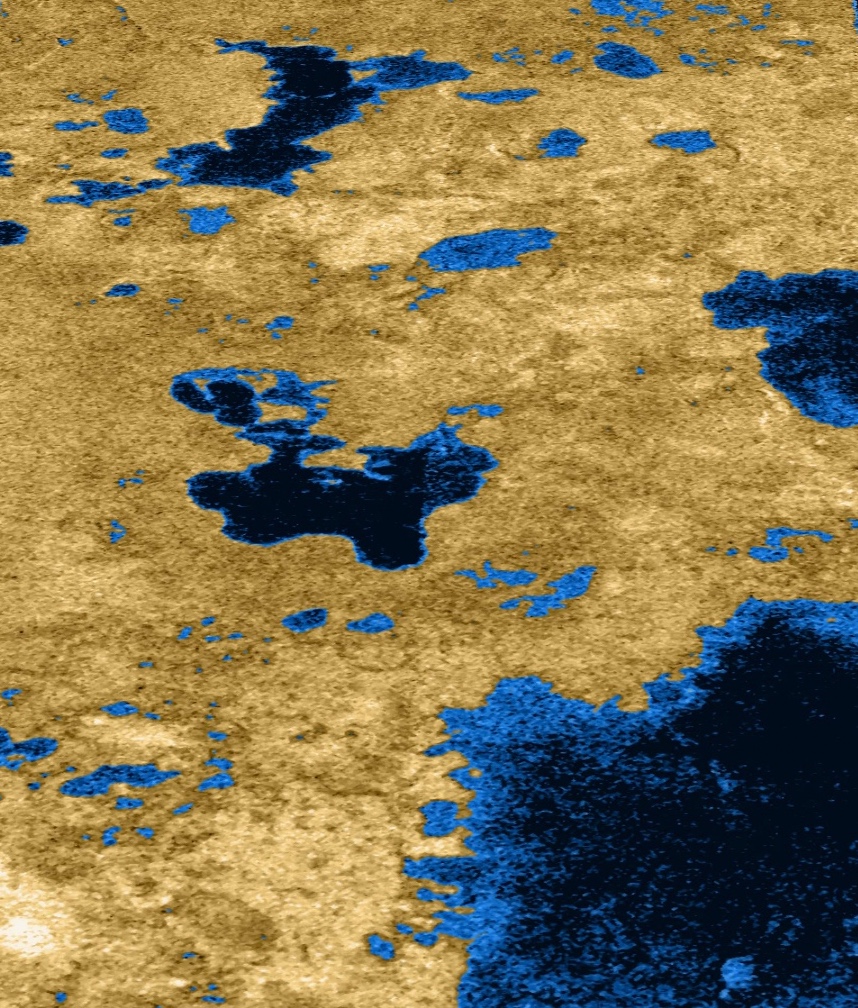

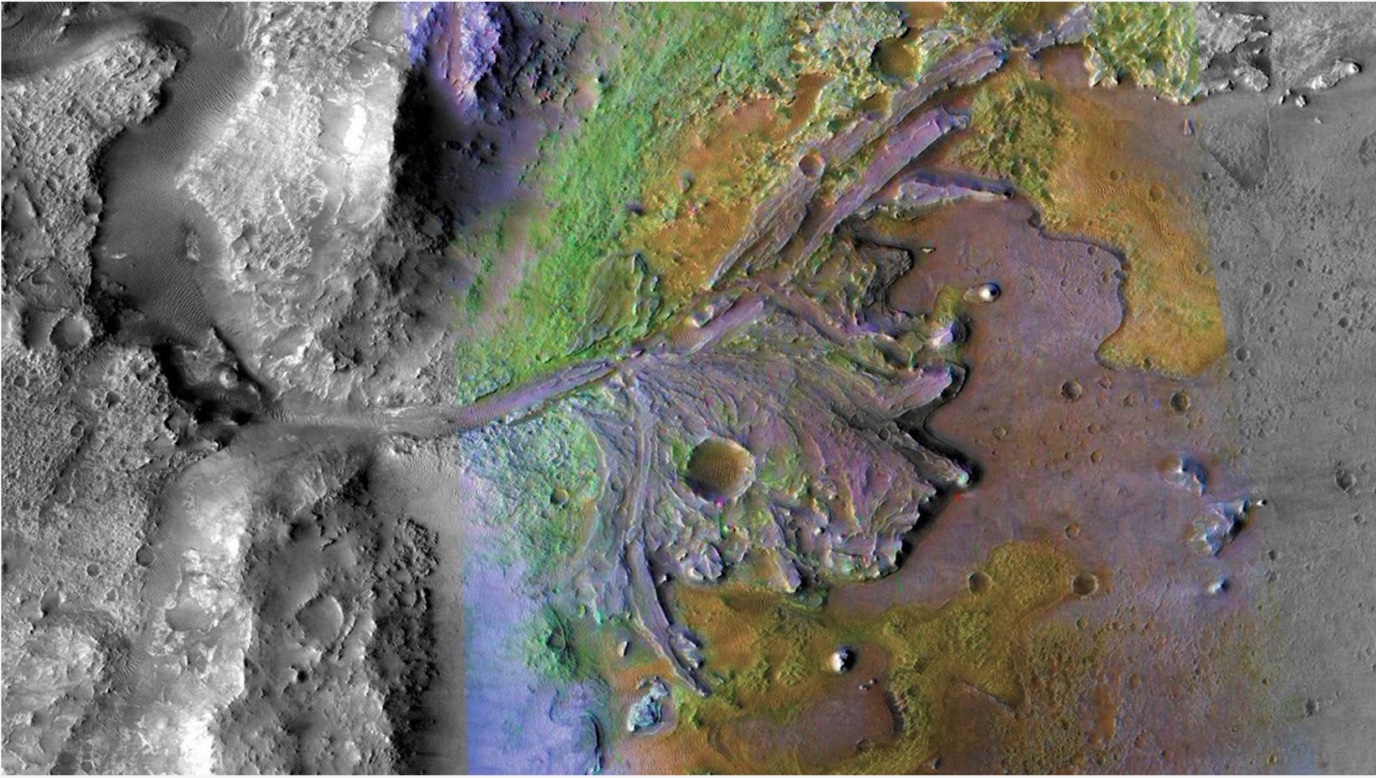

Mars has empty riverbeds, Enceladus (one of Saturn’s moons) has liquid water below a layer of ice, and Titan (another of Saturn’s moons) has an atmosphere and liquid hydrocarbons. These are conditions that may enable or have enabled life. It is only when you see something unusual happening in the atmosphere that you genuinely have an indication of potential life, according to Van der Tak: ‘You see, the Earth’s atmosphere contains both oxygen and methane. These gases should not be able to exist alongside each other because they would immediately react with each other. Nevertheless, these gases are present because the methane gas is continually supplemented by the cycle of life.’

Van der Tak is hoping to see something like that with the upcoming international LIFE mission, something he is currently working on for SRON, the Space Research Organisation Netherlands. A new space telescope is going to observe directly a few hundred planets outside our Solar System. Such exoplanets are at present mainly observed indirectly, as a shadow in the light of a star behind them. By eliminating that light using smart techniques, the LIFE mission will make it possible to take direct measurements, for example of the temperature of the exoplanet.

By the way, this mission is not aimed at taking photographs of extraterrestrial beings. ‘I am searching for something like bacterial life,’ says Van der Tak. ‘Or actually, only for something unusual in the atmosphere that may be an indication of life. ‘What that something unusual is, you never really know beforehand.’

Life within our Solar System

‘I don’t think there’s any intelligent life nearby,’ says Van der Tak, ‘otherwise, we would already have picked up signs of that.’ But it is very well possible that there could be, or has been, a form of life within our Solar System, he explains. ‘There used to be liquid water on Mars since it has empty riverbeds. Furthermore, scientists found a mineral that, on Earth, is only produced by bacteria’. It is, therefore, possible that there has been life, but that it is there no longer because the temperature is too low and the air too thin.

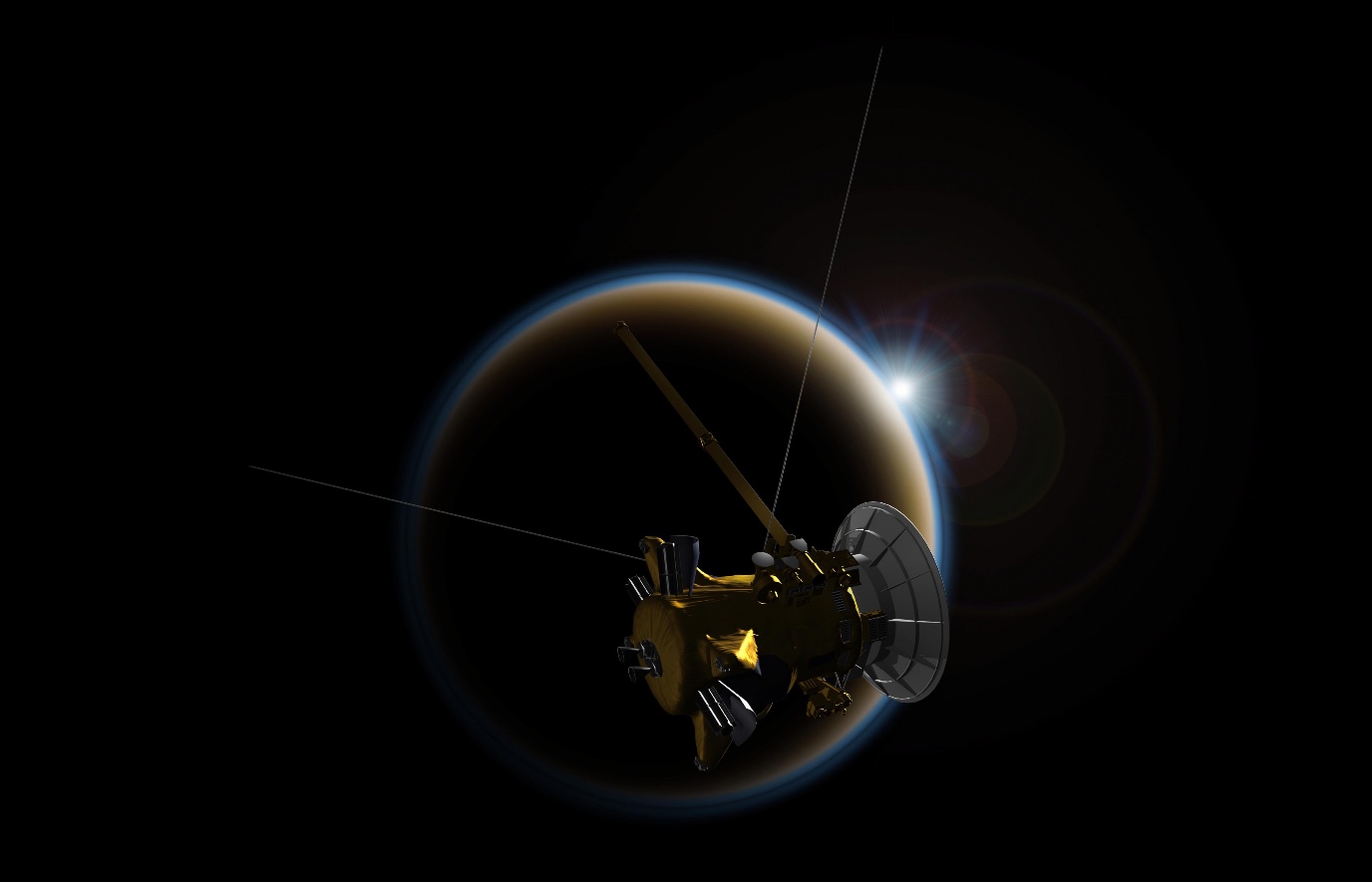

‘And it would certainly be worthwhile to have another look on Titan,’ says Van der Tak, ‘because of the liquid hydrocarbons and the atmosphere there.’ In 2005, the Huygens space probe landed on Titan and did not find any evidence of life. But using more modern means it is possible that more would be found, states Van der Tak.

Can we extend the boundaries of the habitable zone?

Planets where life is possible must, at least, meet three conditions-- Floris van der Tak

‘We are currently drawing up lists of likely candidate planets where life might be possible,’ says Van der Tak. ‘Planets where life is possible must, at least, meet three conditions: (1) there must be liquid water; (2) there must be an atmosphere; and (3) there must be some kind of solid surface.’ Okay, that water could also be a different liquid, for example Titan’s liquid hydrocarbons.

But let us assume for the moment it is water: in that case, a planet must be at a certain distance from its star for the water to be liquid. That distance is referred to as the habitable zone, within which the temperature is just right. ‘However, this relies on all kinds of assumptions,’ explains Kamp. ‘A planet’s temperature is also determined by the gases in its atmosphere; think of the greenhouse effect that we are familiar with here on Earth. So maybe liquid water is possible outside that habitable zone, depending on the planet’s composition.’

What forms of life, and why these three conditions?

‘Whenever I talk about the search for life, people are quick to think of plants and animals,’ says Van der Tak. But here on Earth, single-celled organisms without a nucleus are the most common form of life. And over the 4.5 billion years that our Earth has existed, they were present long before any more complex life forms. ‘Extraterrestrial life can, of course, also take on very different forms,’ says Van der Tak, ‘but it is rather difficult to search for those forms.’

On Earth, all life forms need water to transport nutrients within the cell. Hence the condition that there must be liquid water to enable life on another planet — or a different solvent in which life forms can transport their nutrients. And to keep this liquid on the planet, there must be some kind of solid surface and an atmosphere.

The stuff that's baked into a planet

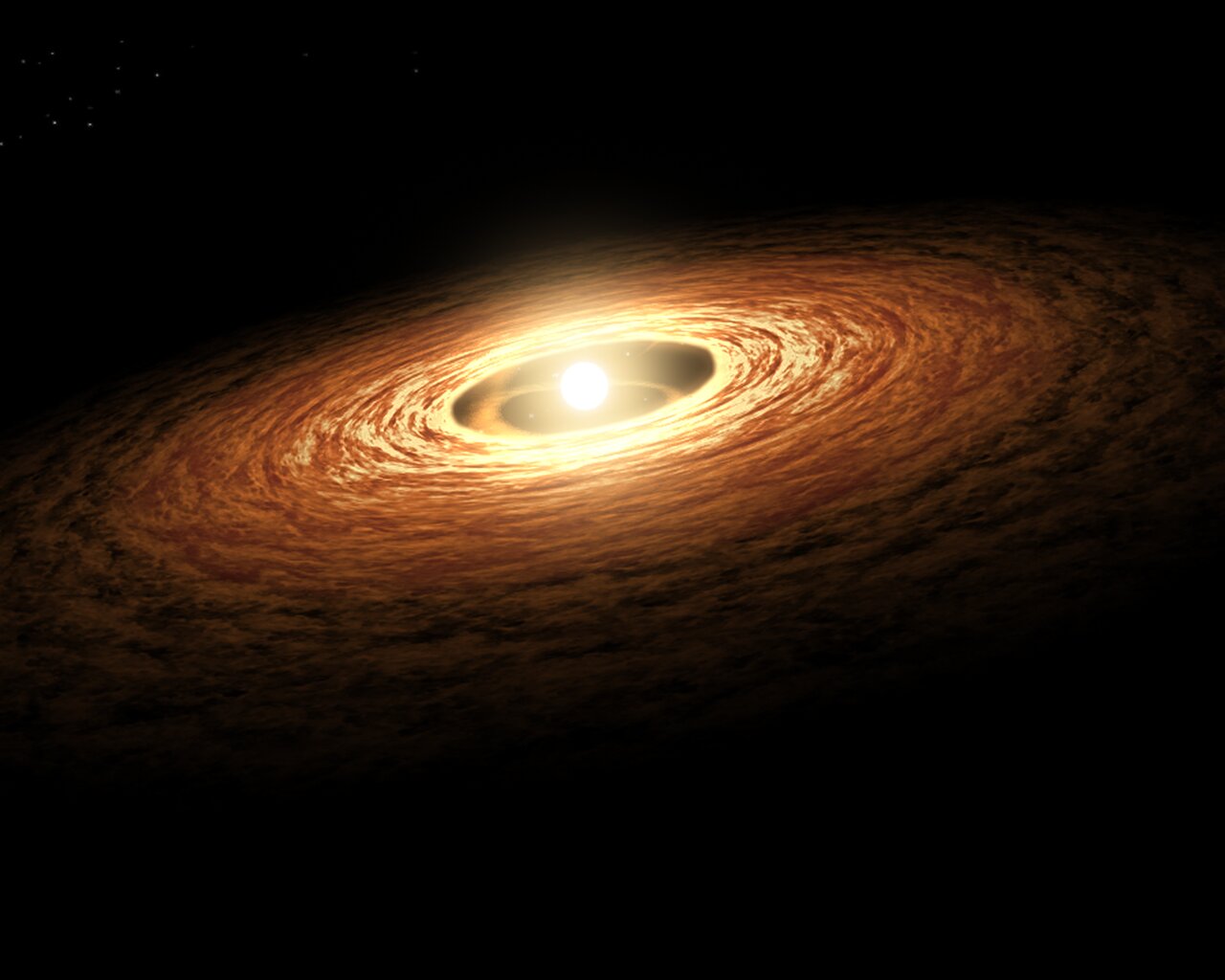

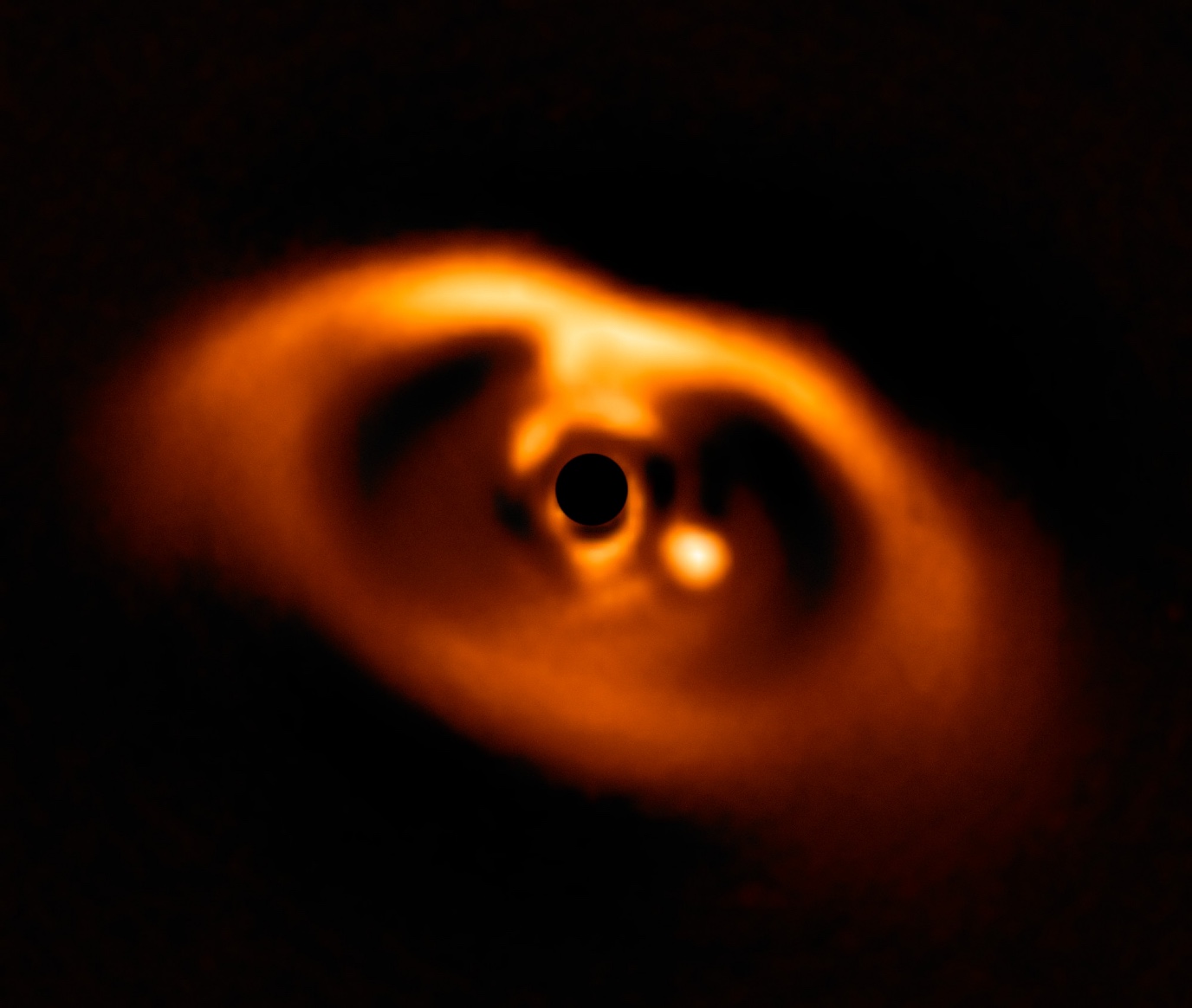

To investigate what planets and their atmospheres could be made up of, Kamp is looking at the phase in which planets first form, in the protoplanetary discs — thin discs made up of gas and dust particles around a young star. ‘Look, you can study existing planets, but you often don’t know much more than their mass and their size. We are looking at the early formation of planets and assume that the material that orbited such young stars in the early phase will become part of those planets.’

Planets start off the same way as the dust under your bed

Protoplanetary discs are made up of dust particles that orbit a young star. Over time, they clump together and, in doing so, form a planet. ‘In that early stage, you can compare them to the dust particles under your bed: they’re still very small and a little fluffy.’ The dust particles easily clump together to form larger structures, still soft and porous. It is only later that they become firm and compact, under the influence of collisions, gravity, and heat.

We would like to broaden the ideas about what a rocky planet could be made up of. That will help us better understand where to search for life-- Inga Kamp

‘We are seeing many different compositions,’ reports Kamp, who often compares hundreds of protoplanetary discs. ‘For example, we are seeing stars that contain much more sulfur than the Sun, which could then potentially be present in their protoplanetary discs.’ Colleagues in the lab showed that that has consequences for a planet’s core and mantle. On Earth we have an iron core, but you would expect iron and sulfur to react with each other in such a sulfur-rich planet. ‘And this, in turn, has consequences for, for example, the magnetic field, the CO2 cycle, and plate tectonics; all of that can be very different on such a planet.’

Furthermore, Kamp and colleagues discovered that the composition of a planet is possibly different in smaller stars compared to stars with a size similar to that of the Sun. And exactly those smaller stars are widespread in the Milky Way and are often on the list of likely candidates for life. Their mass is approximately one tenth of that of our Sun, and the planets near such stars could possibly contain much more hydrocarbons than planets near Sun-like stars. Kamp now wants to find out whether that is indeed the case in a new project for which she recently received a grant. ‘We would like to broaden the ideas about what a rocky planet could be made up of. That will help us better understand where to search for life.’

Read more:

Planetary scientists Quentin Changeat and Tim Lichtenberg investigate the characteristics of exoplanets. Changeat studies the atmosphere of hot Jupiter-like planets, while Lichtenberg is excited to have found an atmosphere around a planet that, according to scientific consensus, was not supposed to have one.

More news

-

14 January 2026

What the smell of the sea does to the clouds above Antarctica