Microplastic research - media hype or real danger?

Are microplastics really as harmful to our health as reports in recent years would have us believe? How many microplastics are actually present in the human body? In an article published by The Guardian on 13 January, scientists express their concerns about unfounded claims and conclusions about microplastics. We asked Barbro Melgert, a microplastics expert at the UG, to interpret this message for us.

FSE Science Newsroom | Leoni von Ristok

Melgert notes, ‘I definitely believe that microplastics are present in the human body. Above all, however, we must distinguish between what we know and what we assume.’

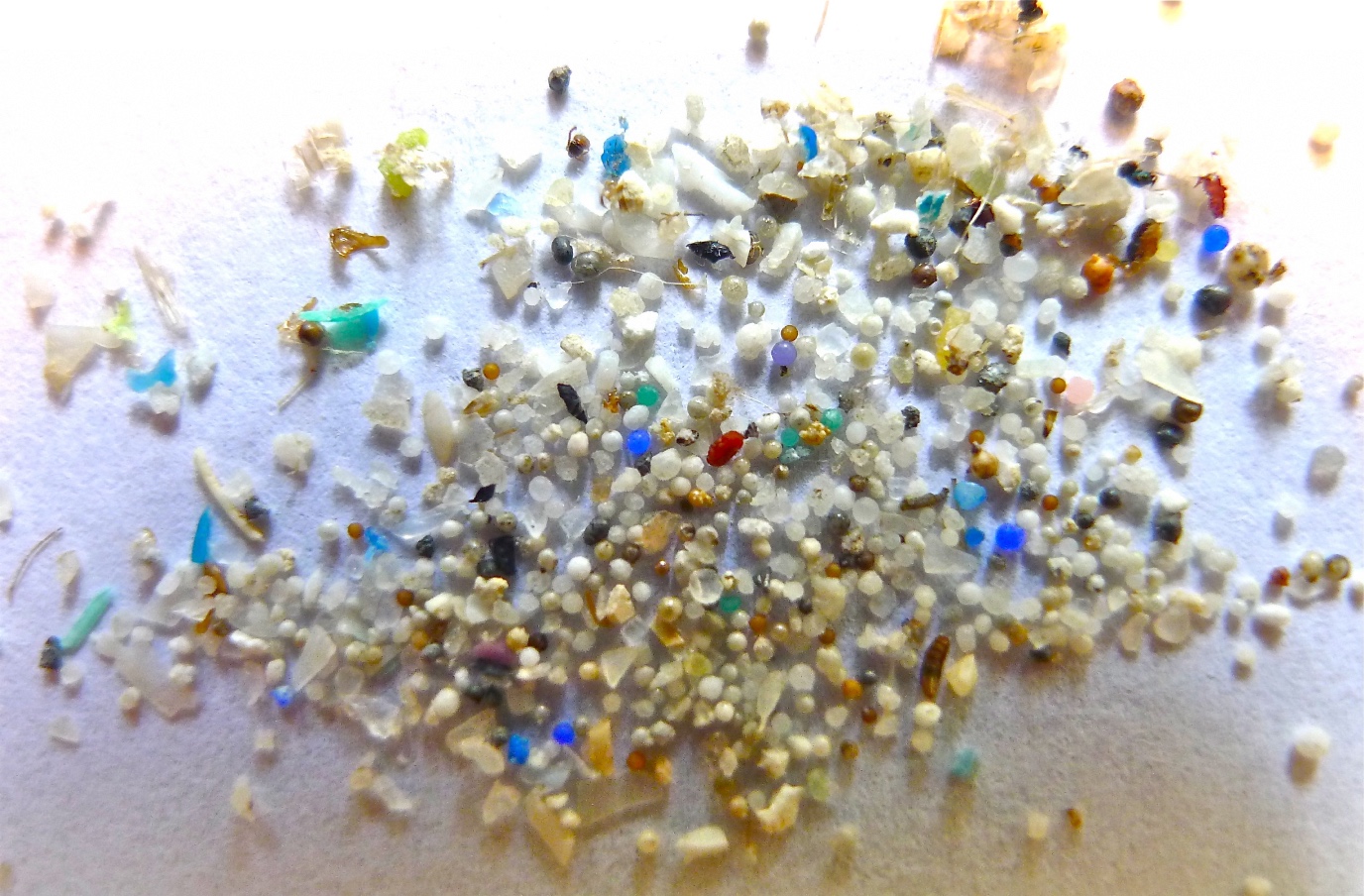

According to the article in The Guardian, ‘There is no doubt that plastic pollution of the natural world is ubiquitous, and present in the food and drink we consume and the air we breathe.’ It is not clear how much of that plastic ends up in our bodies and how harmful it is.

Reliability of the results

Melgert explains, ‘The problem is that we do not yet have any standardised methods for measuring microplastics in the body. This makes it difficult to compare studies with each other.’ It is also difficult to determine whether microplastics are already present in a sample or whether it has become ‘contaminated’ during the investigation.

In addition to the method, the type of sample also influences the reliability of the results. ‘Not all samples are the same,’ stresses Melgert. The reliability of the research depends largely on the way in which it is conducted. According to Melgert, although this may seem obvious, many studies on microplastics are still conducted using tissue samples, for example, even though it is very difficult to draw reliable conclusions from them for some plastics.

Fat or plastic?

Even though microplastics can be measured fairly reliably in blood samples, it is difficult to do so in tissue samples. Taking blood is easy and can be done in a reasonably clean manner. More specifically, during blood collection and analysis, few if any additional microplastics end up in the blood (for example, through the equipment used). Tissue sampling is more complicated, and the risk of contamination with microplastics during or after sampling is greater. Another problem is that the fat in tissue can give off a signal similar to that of some types of plastic, making it unclear exactly what is being measured.

‘As a field, we must work together and help each other to improve standards and develop comparable research methods,’ Melgert asserts. ‘If we start fighting each other, the oil and plastics industries will use that against us, just as the tobacco industry has slowed down action against smoking and is still trying to block action against vaping.’

More news

-

27 January 2026

ERC Proof of Concept grant for Maria Loi

-

26 January 2026

Science for Society | The AI chip of the future