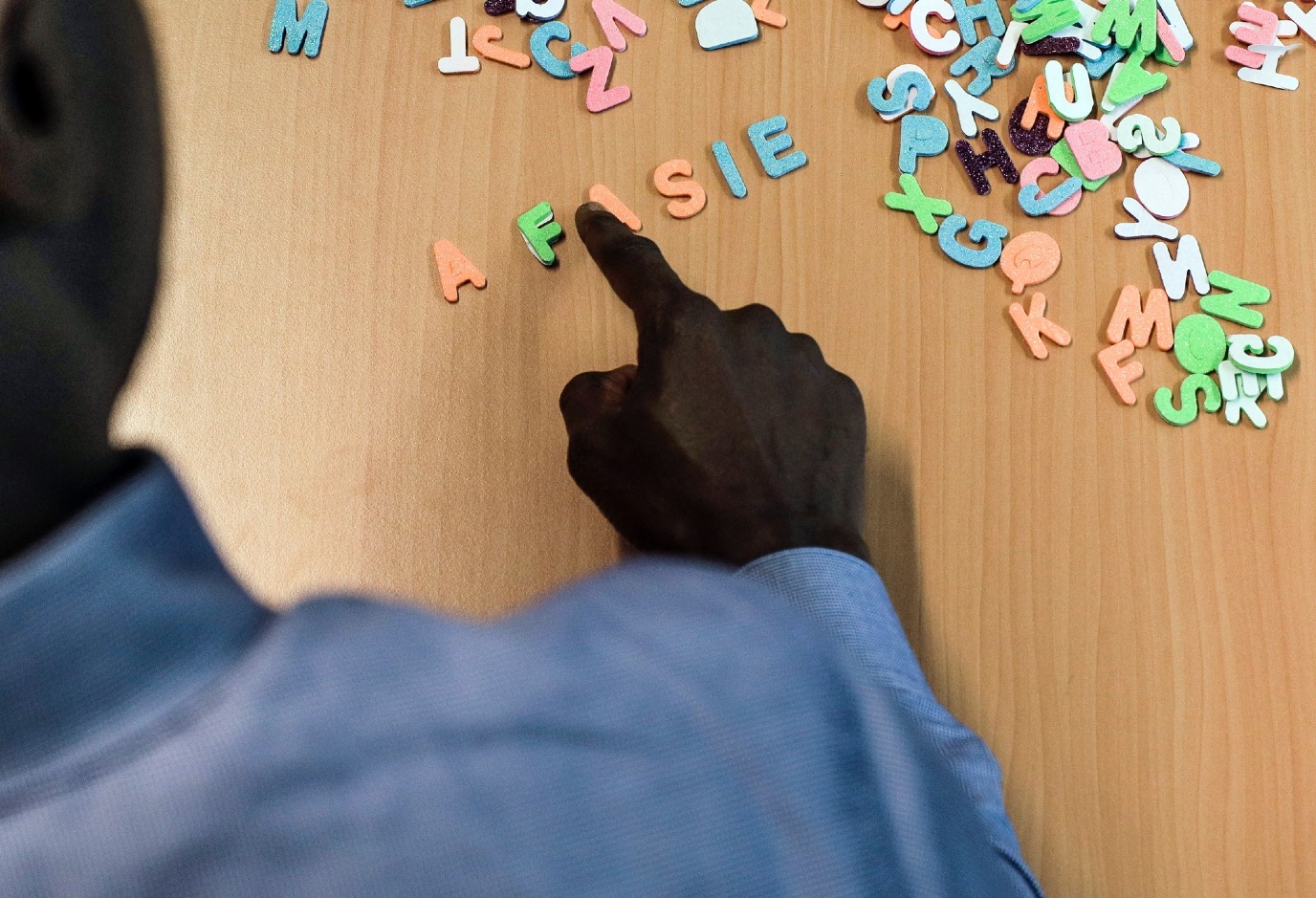

AI-phasia: Artificial intelligence helps with language deficiencies

‘I hope that my research has laid the foundation for a future tool for smartwatches or smartphones.’ Master’s student Thijs van der Laan has developed an AI language model to help people with aphasia find words. His ‘AI-phasia’ research received the Impact Award from the Faculty of Science and Engineering at the University of Groningen in the category Students.

FSE Science Newsroom | Myrna Kooij

You may recognize this situation: you are visiting your grandparents and, suddenly, they get stuck in the middle of a story. They just cannot seem to find that one word they are searching for. What was that called again?

For people with aphasia, this is an everyday occurrence. This language disorder is caused by brain damage (for example, following a stroke). It often affects the language areas of the left hemisphere of the brain, leading to difficulty speaking, reading, or writing.

We speak our sentences from left to right. When we listen, therefore, we have access only to the words that have been spoken before the current word.

A Master’s student in artificial intelligence, Van der Laan focuses on the common anomic aphasia and paraphasia. ‘In concrete terms, these people are often not able to find the right word, or they tend to mispronounce words,’ explains Van der Laan. ‘For example, they might say “uh” a lot, make frequent pauses, or confuse words, saying something like “Can you cold my hand?” instead of “Can you hold my hand?”’

AI model predicts words

Van der Laan likes to think in terms of possibilities. That is why he wanted to investigate whether a language model could help people with aphasia find words. To do this, he used unidirectional large language models, such as those underlying ChatGPT or Gemini. These language models process text from left to right, predicting words based on the given context.

Like in everyday life, context is important for the language model. Van der Laan continues: ‘We speak our sentences from left to right. When we listen, therefore, we have access only to the words that have been spoken before the current word.’ For this reason, his language model mirrors the way we speak.

How to train a language model

Van der Laan used existing language models from Google and Meta as the basis for his research. ‘They have already been trained on much more data than I could ever obtain,’ he says. One problem, however, is that these algorithms do not recognize impaired language, as occurs in aphasia. To address this issue, Van der Laan trained the algorithms on a large American dataset of people with aphasia. ‘Training basically means familiarizing the model with a certain type of text or context,’ he explains. ‘In my case, it consisted of interview data from a large number of people with aphasia.’

The English-speaking participants were given a variety of tasks: from open-ended questions (such as ‘Tell me about your recovery’) to tasks with a clear framework (such as retelling the story of Cinderella using pictures from a book of fairy tales).

The language model had more difficulty when participants were free to choose what they wanted to say. ‘The greatest difficulty in predicting was in the open-ended category, where the interview participants had the most freedom in terms of subject matter,’ explains Van der Laan. ‘You don’t know what they wanted to say.’ It is therefore necessary to verify whether the model’s predicted options include the correct word.

This posed a problem. In the data from people with aphasia, the answer – the ground truth – is often missing behind the hesitation. Van der Laan notes, ‘Sometimes, they do say the intended word afterwards, but not always.’ The data from people with paraphasia offered a solution: ‘The interviews with people with paraphasia did include what should have been said.’ This enabled him to evaluate the predictions of his language model reliably.

From punctuation marks to useful words

In one of the first versions, the language model also predicted a wide range of punctuation marks. ‘I noticed that many predictions were actually useless text units, such as full stops, commas, or personal pronouns.’ These are not very useful in practice, because when people are talking and cannot think of a word, they rarely look for a full stop.

To this end, Van der Laan adjusted part of the mathematical function while training the language model. ‘This makes the model less inclined to predict these kinds of superfluous things, thus yielding better predictions with a higher probability.’ The model is therefore more suitable for use with spoken language.

A Master’s research project with impact

Van der Laan’s Master’s thesis played a major role as a pilot in a grant application submitted by his supervisor, Frank Tsiwah. ‘What he did was a pilot project for my grant, and I included a statement in my application that I had already tested this idea,’ says Tsiwah proudly. ‘That gave them the confidence that this could work.’

The application was successful. Tsiwah recently received a large grant from the Dutch Research Council (NWO) to continue the research. The next step will involve adding speech recognition for spoken Dutch. ‘I am going to collect the Dutch data myself,’ explains Tsiwah. ‘The English-language dataset is available, and Thijs based his research on a part of that dataset.’

In collaboration with AfasieNet Nederland, Tsiwah is eager to lay the foundations for an AI tool (such as a mobile phone app) that can support people with language disorders during conversations and help them to find the right words.

As for Van der Laan, after graduating, he opted to pursue a Business & IT traineeship at Rabobank. Tsiwah and Van der Laan are still in touch with each other, regularly meeting for coffee. ‘Whenever possible, I still try to get involved with AI in this role, but mainly from a strategic or advisory perspective,’ explains Van der Laan. ‘I don’t think I’d be happy just sitting behind a computer coding all day. I think it would be nice to actually work with people

A report on the award ceremony can be found on the FSE news page.

More news

-

06 January 2026

Getting to grips with the workhorses of our body

-

19 December 2025

Mariano Méndez receives Argentine RAÍCES award