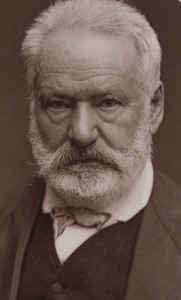

Be Welcome: Lessons in Hospitality from Victor Hugo and Monseigneur Bienvenu Part Two

Following on from Tuesday’s post, Erin Wilson writes more on how the faithful hospitality of Victor Hugo’s character Monseigneur Bienvenu from Les Miserables can contribute to contemporary political issues, in particular statelessness and migration.

The problem of statelessness emphasises most acutely the power imbalance that exists within global politics between the state and individuals. Hannah Arendt articulates one of the most poignant and tragic interpretations of this power imbalance. In speaking of the plight of refugees, and in particular Jewish refugees, in the 1930s and 1940s, Arendt highlights the hopelessness of their situation:

‘they had lost those rights which had been thought of and even defined as inalienable, namely the Rights of Man. The stateless and the minorities… had no governments to represent and to protect them and therefore were forced to live either under the law of exception of the Minority Treaties [of the League of Nations], which all governments… had signed under protest and never recognized as law, or under conditions of absolute lawlessness’.[1]

Having herself had to live in a state of lawlessness as a result of fleeing Germany without any legal travel documents,[2] Arendt was all too familiar with the fate of the stateless and minorities that she here describes. The great irony and tragedy of the emergence of supposedly ‘universal’ human rights is that these rights require an institution to uphold and enforce their recognition. In theory this is done by the state. Yet, as Arendt notes, these rights ‘proved to be unenforceable – even in countries whose constitutions were based upon them – whenever people appeared who were no longer citizens of any sovereign state.’[3] Individual human beings, despite being apparently entitled to certain ‘inalienable’ rights by virtue of being human, are unable to claim those rights unless they enjoy membership or citizenship in a state. Thus, the state ultimately holds the power of life and death over individual human beings, whatever may be said about universal human rights.

There are few other institutions or organisations that have the capacity or authority to be able to intervene against the power of the state on behalf of the individual in contemporary politics. Yet the moral authority which many religious traditions and organisations possess in domestic and global politics, as well as their nominal independence from political authorities, coupled with their commitment to faithful hospitality to the stranger, at least opens up the possibility that religious actors can in some way offset the harsh responses of states and provide greater protection and welcome to stateless persons.[4]

There are numerous examples of religious organisations doing just that. Churches in the US during the 1980s directly violated US immigration law by providing sanctuary to asylum seekers from El Salvador and Guatemala deemed to be illegal immigrants by US authorities. Protestant churches in Switzerland[5], churches working with 14 communities across the UK to declare their cities, including London, Oxford, Nottingham, Sheffield and Bradford, to be ‘cities of sanctuary’ for asylum seekers.[6] Similar asylum and sanctuary services are offered in Australia by Baptcare and Hotham Mission Asylum Seeker Project. Another older, famous example is the Huguenot community in Le Chambon, France, who sheltered Jewish refugees during World War Two.[7] In Germany, the Asyl in der Kirche (Asylum in the church) network emerged unofficially in the early 1980s in response to German government attempts to deport Kurdish and Lebanese asylum seekers, despite the unrest that existed in their respective homelands, with individual parishes offering asylum.[8] As more parishes developed church asylum policies and procedures, a formal organisation was established in the early 1990s, around the same time as the right to asylum in Germany became significantly reduced.[9] The movement has continued to grow and expand, with a now European wide sanctuary movement.[10]

In most instances, religious organisations who provide asylum and sanctuary also engage in broader campaigning and advocacy in order to alter policies perceived as unjust towards asylum seekers and refugees. One recent example is the Vluchtkerk network in Amsterdam, a network of churches, individuals and aid organisations that has sprung up in support of a group of asylum seekers sheltering in a disused church in Amsterdam.[11] Other examples from Australia include The National Council of Churches, which has been involved in opposing Australian government policy toward asylum seekers since the early 1990s, in particular mandatory detention.[12] Other religious organisations have spoken out in the media to raise awareness about the consequences of Australia’s harsh policies towards refugees and asylum seekers.[13] FBOs and churches have formed campaign networks and movements, such as Justice for Asylum Seekers (JAS) and used these networks to organise campaigns, rallies, and other forms of protest to raise awareness and advocate for change of policies towards asylum seekers.[14] As well as utilizing religious arguments, identified earlier as the basis for faithful hospitality, these actors draw on standards set out in international law to argue for changes in policy and practice.

A final point regarding faithful hospitality that is relevant, particularly to migration debates. A key feature of this type of hospitality is that it is transformative. Jean Valjean Valjean, the hardened criminal, cynical and resentful, is transformed into a compassionate, self-sacrificing and generous person largely through his encounter with the bishop’s faithful hospitality. Yet so too is the Bishop, not just because he gave away his silver, but because the experiences Valjean relates to him about being a prisoner in the galleys, in a way became the Bishop’s own experiences. In the language of hospitality, both Valjean and the Bishop occupy the roles of host and guest, meaning that there is an inherent equality between them both – Valjean is the guest in the Bishop’s home, yet the Bishop becomes a guest in Valjean’s life – invited in to share his experiences. These are important dimensions to bear in mind in the policy areas of statelessness and homelessness. Too often, asylum seekers, refugees and homeless persons are treated as objects on which state policy and social outreach or welfare are enacted, rather than active subjects and agents of societal transformation. Further, they are often depicted as the only beneficiaries of a state’s hospitality. Yet it is not just they who benefit from the hospitality of the state or the society or the church or the community group, but equally our societies benefit from their hospitality – their willingness to share their talents and experiences with us and invite us to become part of their lives, thereby enriching our own lives.

Erin Wilson is Director of the Centre for Religion Conflict and the Public Domain, Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Groningen. The ideas in this blog post are taken from her paper, “Be Welcome: Religion, Hospitality and Statelessness in International Politics”, first presented at the workshop “Hospitality in World Politics” in July 2010. The chapter is forthcoming in Hospitality in World Politics, edited by Gideon Baker and published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2013.

[1] H. Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, London: Allen and Unwin, (1958), pp268-9

[2] Bernstein, ‘Arendt on the Stateless,” 46-7

[3] Arendt, Origins of Totalitarianism, p293

[4] I recognise that not all religious authorities or organisations are independent from state authorities, particularly in many Islamic countries where the two are essentially the one entity. I am particularly focused here on the resettlement context of Western/developed states in global politics, where the separation of church and state is largely accepted and part of broader social structures. How neat that separation may be is open to question, but for now, I assume that religious institutions and organisations possess a level of independence and autonomy from state authorities.

[5] C. B. Ecoffey. ‘Asylum in Switzerland: A Challenge for the Churches’, University of Manchester Masters Dissertation. Available at Site oikumene Accessed 16 June 2010.

[6] City of Sanctuary, ‘Who is involved?’ City of Sanctuaryhttp://www.cityofsanctuary.org/cities Accessed 30 June, 2010

[7] Hallie, ‘From cruelty to goodness’, 26

[8] I. I. Koop. ‘Refugees in Church Asylum: Intervention Between Political Conflict and Individual Suffering’, Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology vol. 11, no. 3 (2005), 355-6; Mittermaier, ‘Church Asylum in Germany’, 3-4

[9] Mittermaier, ‘Church Asylum in Germany’, 4

[10] Conference of European Churches, ‘European Churches Responding to Migratio’, http://www.migration2010.eu/ (2010) Accessed 30 June 2010.

[11] For more information, see http://www.devluchtkerk.nl/home

[12] D. Gosden, ‘”What if no one had spoken out against this policy?” The rise of asylum seeker and refugee advocacy in Australia’ Portal Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies, vol. 3, no. 1 (2006), 2

[13] M. Vincent, ‘Returned asylum seekers killed, jailed: advocate’, ABC News 19 May 2010, http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2010/05/19/2903429.htmAccessed 30 June 2010

[14] Coleman, C. Director of Hotham Mission Asylum Seeker Project. Interview concerning FBOs and asylum seekers in Australia, 6 September, 2010.