Why do we care so much about the fate of religion?

On 4 September this year, the national Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant published an article profiling recent sociological research on rising secularisation around the world. Debate over whether the disappearance of religion was something universal or something confined to the West has raged for decades. This new research seemed to definitively show that religion was on the way out everywhere. Different regions of the world were simply at different stages in the inevitable march towards religion’s extinction. The research seemed to settle once and for all that religion was indeed on the way out.

Yet just one month prior to publishing this article, De Volkskrant also published an article about online belief, quoting 2024 research from the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics saying that religion was on the rise amongst Gen Z. Recent data from across Sweden, the UK and the US tell a similar story.

So which is it? Is religion growing or declining?

As with all research, the question comes back to what it is you are actually studying. And that’s the problem with studying religion. There is no single agreed on definition. Most people have a kind of “we know it when we see it” approach to religion, but that doesn’t work when you’re trying to measure and count something. Even research that works with a fixed definition is problematic, because usually such definitions are based on Western models of Christianity. That is a problem with this latest research that suggests religion is declining globally. What they are interested in is not necessarily individual spirituality or engagement with the transcendent, but rather people’s adherence to organised, established world religions. They measure this decline in religiosity through looking at people’s participation in public rituals, how important religion is to people, and people’s religious affiliations. To take issue with just one of these categories – recent research from Pew, one of the datasets Stolz et al draw on, shows that the category of “nones” (no religion) has increased by 10% globally in the last ten years. This category, however, includes people who are atheists, agnostics and religiously unaffiliated. But, as Pew themselves note, religiously unaffiliated does not mean that these people are not engaged in spiritual practice. There is growing sociological and anecdotal evidence that people do not want to explicitly associate with a specific religious tradition, but nonetheless spirituality remains an important part of their life. The so-called “Emerging Church” Movement is just one example of this. A phenomenon that is frequently referred to as “deconstructing traditional Christianity”, deconstruction is also perhaps the only thing that unites the different communities sociologists group under the label of Emerging Church. Many people engaged in processes of deconstruction would not necessarily identify themselves with this label at all, or with any other label, for that matter. So this recent research that says religion is declining might be right. But the research that says it is growing may also be right. It all depends on how we choose to define it.

But perhaps the more fundamental question is – why do we care so much? Why are we so obsessed with this question of whether religion is growing or declining?

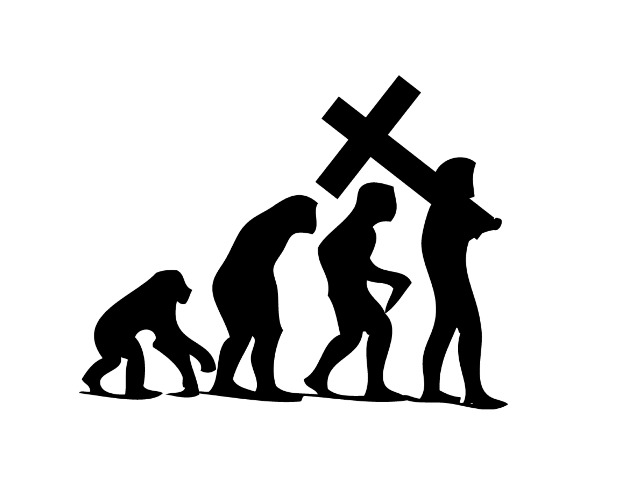

Because in a secular Western mindset, it isn’t just about what religion is, it’s about what religion symbolises and what we think the growth or decline of religion signifies about our species. How we think about our own relationship with religion, as individuals and as a species. The fate of religion isn’t just an interesting sociological or historical question. We have endowed it with moral and normative assessments of human intelligence and character. In the West, at least, we see religiosity or lack thereof as a sign of our inherent capacity for growth and development. If we are becoming less religious, then, we think, we are becoming more advanced and developed, more enlightened, more rational and more intelligent. If we are becoming more religious, then we are regressing, becoming more ignorant and irrational.

And all of this is premised on highly normative assumptions about the value of religion itself. We assume – often implicitly and subconsciously – that religion is a negative for society. That it is primitive, backward, irrational and contributes to violence and ignorance. Our studies of religion are biased before we even begin them. And this distorts our analysis of religion as a sociological, anthropological, historical, and, crucially, political factor.

If we really want to understand what is happening with religion in our world today, we must start with context. Because religion means different things to different people in different times and places, we must first establish where and when we are looking at religion. We also need to recognise that religion isn’t just an isolated phenomenon. Religion shapes and is shaped by factors in the surrounding context, such as politics, economics, the environment. We must take these things into account as well. Finally, the word “religion” itself is used as shorthand not only for a huge diversity of traditions, beliefs and practices, but also for everything from institutions and NGOs with religious affiliations, to identities and communities to rituals, myths, images and narratives. We need to be conscious when we use the word “religion” that it could refer to anyone of these things – and then be precise and explicit about which one we are referring to.

Approaching the study of religion through this framing helps to overcome both the definitional problem, and to treat religion as any other sociological and anthropological factor of analysis, rather than muddying the discussion with our normative assumptions about what the fate of religion means for us as human beings.

About the author

Erin Wilson is Professor of Politics and Religion in the Faculty of Religion, Culture and Society at the University of Groningen.