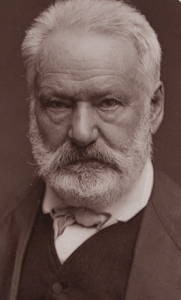

Be Welcome: Lessons in Hospitality from Victor Hugo and Monseigneur Bienvenu Part One

Erin Wilson reflects on the religious themes present within Les Miserables and how they speak to contemporary political issues.

My husband and I went to see the latest film adaptation of Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables over the weekend. As a long time fan of the story and the musical, I have always been struck by the significance of the Bishop. A character who has perhaps 10 minutes at the most on stage/screen, and occupies a minute portion of the epic novel, he is nonetheless critical to the story. Without the Bishop’s intervention, Valjean would have been returned to prison and there would have been no story to tell.

The film with Hugh Jackman, Anne Hathaway and Russel Crowe has invited numerous commentaries on its religious themes, including grace and justice,[1] redemption and salvation, and prayer.[2] In today’s post, I want to pick up on a slightly different theme that Les Miserables, particularly the Bishop of Digne, invites us to think about – hospitality to the stranger – and what religious approaches to hospitality may be able to contribute to important issues of public policy in contemporary life. I’m not talking about contemporary kinds of hospitality that most of us are familiar with – the hospitality industry, or inviting round family and friends who are most likely in a position to reciprocate. I’m referring to abundant, generous hospitality offered to people we do not know and without any expectation of reciprocity.

Let’s first of all consider the character of the Bishop a little more closely, and for this we need to draw on the background provided in the book. Hugo takes considerable time establishing the character and experiences of the bishop, a man so generous and welcoming that his parishioners refer to him as “Monseigneur Bienvenu”. Already the character’s name hints at the significance of his hospitality. One of Hugo’s primary goals in writing the character of the Bishop was to emphasise how different Monseigneur Bienvenu’s behaviour was in comparison to that of other bishops of the day. Indeed, in an argument with his son over the character of the bishop, Hugo asserted that ‘this Catholic priest, this pure and lofty figure of true priesthood, offers the most savage satire on the priesthood today’.[3] For Hugo, then, a “true” priest, one might even say a true believer, of any religion, is distinguished by their humility, their generosity, their hospitality.

The following exchange between Valjean and the Bishop provides an insight on this:

‘Monsieur Curé,’ said the man, ‘you are good; you don’t despise me. You take me into your house; you light your candles for me, and I haven’t hid from you where I come from, and how miserable I am.’

The bishop, who was sitting near him, touched his hand gently and said: ‘You need not tell me who you are. This is not my house; it is the house of Christ. It does not ask any comer whether he has a name, but whether he has an affliction. You are suffering; you are hungry and thirsty, be welcome. And do not thank me; do not tell me that I take you into my house. This is the home of no man, except him who needs an asylum. I tell you, who are a traveller, that you are more at home here than I; whatever is here is yours. What need have I to know your name? Besides, before you told me, I knew it.’

The man opened his eyes in astonishment:

‘Really? You knew my name?’

‘Yes,’ answered the bishop, ‘your name is my brother.’[4]

What Hugo seems to be trying to say is that the bishop is not hospitable because he is a bishop, or because he is ‘religious’. The bishop is hospitable because of his own deep personal faith experience and conviction regarding the love of God for humanity.[5]

For this reason, I prefer to use the term “faithful hospitality” as opposed to religious or biblical hospitality or some other term. It seems important to use a term that is broadly inclusive of a number of different religious traditions. While ‘religious’ or ‘faith-based’ hospitality may have achieved the same connotation, I also think it’s important to emphasise that this type of hospitality is often displayed by people who hold a deep, personal, intimate faith, not simply those who engage in religious rituals or observances. They take the commandments found in the sacred texts seriously, are deeply and personally influenced by their own faith experiences and offer unconditional ‘faith-filled’ hospitality on this basis. It seems significant to make this distinction, since it highlights that not all actors who classify themselves as ‘religious’ would offer hospitality. Indeed, often it is religious actors who are the most inhospitable towards ‘others’, including members of different faith traditions and different lifestyles.[6]

So what makes faithful hospitality distinct from other notions of hospitality? The central point of significance, across different religious traditions, seems to be both the knowledge and the experience of God’s love for the whole of humanity. Muddathir ‘Abd al-Rahim highlights a long tradition of hospitality towards asylum seekers and refugees in Islam coming directly out of the belief that all human beings have been transformed by God’s love and grace and thus possess dignity that makes them worthy of compassion and respect.[7] Timothy Keller has argued that it is the transformative power of God’s grace that inspires (or should inspire) Christians to pursue justice on behalf of the poor, oppressed and vulnerable.[8] Pohl has also highlighted the notion of the sacredness of the human being in Christian doctrine, particularly the writings of John Calvin with regard to hospitality to strangers.[9] Every human being is believed to be marked with the image of God, establishing ‘a fundamental dignity and value that cannot be undermined’.[10] Elie Wiesel emphasises the same belief within the Jewish tradition – ‘Any human being is a sanctuary. Every human being is the dwelling of God – man or woman or child, Christian or Jewish or Buddhist. Any person, by virtue of being a son or daughter of humanity, is a living sanctuary whom nobody has the right to invade’.[11] This view that all human beings are reflections of the divine in one way or another lies at the heart of much social justice work that religions engage in.[12]

Seeking justice, then, becomes an integral part of the purpose and practice of faithful hospitality. Faithful hospitality not only includes welcoming the stranger through the provision of food, shelter, clothing and relationship, but also advocating with and for the stranger against those seeking to oppress, exploit or exclude them. Extending this idea further, hospitality involves challenging established power structures and redistributing power from the centre to the margins.[13]

Hugo’s Monseigneur Bienvenu again provides an example of this when he intercedes on Valjean’s behalf with the gendarmes:

‘Silence!’ said a gendarme, ‘it is monseigneur, the bishop.’

In the meantime, Monsieur Bienvenu had approached as quickly as his great age permitted:

‘Ah, there you are!’ said he, looking towards Jean Valjean, ‘I am glad to see you. But! I gave you the candlesticks also, which are silver like the rest, and would bring two hundred francs. Why did you not take them along with your plates?’…

‘Monseigneur,’ said the brigadier, ‘then what this man said was true? We met him. He was going like a man who was running away, and we arrested him in order to see. He had this silver.’

‘And he told you,’ interrupted the bishop, with a smile, ‘that it had been given him by a good old priest with whom he had passed the night. I see it all. And you brought him back here? It is all a mistake.’

‘If that is so,’ said the brigadier, ‘we can let him go.’

‘Certainly,’ replied the bishop.[14]

By interceding in this way, the bishop uses his own authority – legally as the owner of the silver, but also morally as a religious leader – to take the power over Valjean’s life away from the gendarmes and give it back to Valjean.[15] Part of faithful hospitality then is interceding and advocating, ‘standing in the gap’, for those who are dispossessed and powerless in an effort to alter established power structures.[16]

All well and good, but how does any of this relate to contemporary political issues? While I think faithful hospitality has much to contribute to all areas of politics where people are discriminated against, marginalised and excluded, there are two key areas where the intervention of faithful hospitality could make a substantial contribution – homelessness and statelessness. I’m going to focus on statelessness, as it’s what I’m more familiar with, but I suspect there are many similarities and overlaps between the two policy areas. More in Part Two.

Erin Wilson is Director of the Centre for Religion Conflict and the Public Domain, Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Groningen. The ideas in this blog post are taken from her paper, “Be Welcome: Religion, Hospitality and Statelessness in International Politics”, first presented at the workshop “Hospitality in World Politics” in July 2010. The chapter is forthcoming in Hospitality in World Politics, edited by Gideon Baker and published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2013.

[1] J. McKenna, 2013, “Do you hear the people sing? M.L. King and Les Miserables ’ case for a Socialism of Grace” Red Letter Christians, Available at http://www.redletterchristians.org/do-you-hear-the-people-sing-m-l-king-les-miserables-case-for-a-socialism-of-grace/ J. Toh, 2012, “Embodying grace: Les Miserables and the meaning of Christmas” ABC Religion and Ethics, Available at http://www.abc.net.au/religion/articles/2012/12/24/3660235.htm

[2] V. Dixon, 2013, “What Les Miserables teaches about prayer,” The Washington Post Available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/guest-voices/post/what-les-miserables-teaches-about-prayer/2013/01/16/0c42fcd8-600b-11e2-9940-6fc488f3fecd_blog.html

[3] Vargas Llosa, The Temptation of the Impossible, p64, emphasis added

[4] V. Hugo, Les Miserables, p51

[5] Vargas Llosa, The Temptation of the Impossible, pp62-3

[6] L. M. Russell, Just Hospitality: God’s Welcome in a World of Difference. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press (2009), p78

[7] M. ‘Abd al-Rahim, ‘Asylum: A moral and legal right in Islam’, Refugee Survey Quarterly, vol. 27, no. 2 (2008), 16-7

[8] T. Keller, Generous Justice: How God’s Grace Makes Us Just, New York: Hodder and Stoughton (2010)

[9] Pohl, ‘Responding to Strangers’, 86

[10] Pohl, ‘Responding to Strangers’, 86; See also J. D. Carlson, ‘Trials, Tribunals and Tribulations of Sovereignty: Crimes Against Humanity and the imago Dei’, in J. D. Carlson and E. C. Owens (eds). The Sacred and the Sovereign: Religion and International Politics. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press (2003), pp199-200; M. J. Erickson, Christian Theology. Second Edition. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books (1998), p518.

[11] Wiesel, ‘The Refugee’, p9

[12] M. A. Johnson, K. Jung and W. Schweiker, ‘Introduction’ in W. Schweiker, M.A. Johnson and K. Jung (eds). Humanity Before God: Contemporary Faces of Jewish, Christian and Islamic Ethics. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, (2006), pp 6-10; T. Lorenzen, ‘Freedom from Fear: Christian Faith and Human Rights Today’, Pacifica, vol. 19, no. 2 (2006), 204; E. K. Wilson, ‘Beyond Dualism: Expanded Understandings of Religion and Global Justice’, International Studies Quarterly, vol. 54, no. 3 (2010), 733-754; J. Haynes, Religion and Development: Conflict or Cooperation? Houndsmill, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, (2007), p16

[13] Ibid, p44

[14] Hugo, Les Miserables, p72

[15] It is important to note that this is but one interpretation of the power of the Bishop’s actions here. Hugo later has the bishop declaring that through the gift of the silver, the Bishop has bought Valjean’s soul and given it to God, reclaimed it from evil and returned it to good (Hugo, Les Miserables, p73). From the moment Valjean leaves the Bishop, however, it becomes his own choice as to whether he uses his new found freedom for good or for evil, regardless of the Bishop’s stated purpose. Nonetheless, the immediate effect of the Bishop’s actions is to remove the power of the state over Valjean and to return to him his right of self-determination.

[16] Asyl in der Kirche (ed). 2007. “Basic Information on Church Asylum.” German Ecumenical Committee on Church Asylum. Available at http://migration.ceceurope.org/fileadmin/filer/mig/50_Materials/20_Publications/Basic_information_on_Church_Asylum.pdf Accessed 29 June 2010; Keller, Generous Justice; Pohl, “Responding to Strangers,” 82