Religious or political? Or both? Religious rituals as political activism

Today’s post from Erin Wilson continues some reflections on fasting from last week, asking whether fasting is just religious or political or if in fact sometimes it can be both.

In a post last week on Ash Wednesday, Marten van de Meulen noted that it’s not just Christians who’ll be fasting this Lent. He referred to a secular environmentalist campaign “40 Days without Meat”, where participants give up meat for the period of Lent in an effort to reduce their impact on the environment and to raise awareness of important environmental issues.[1]

But is it just those who are secular and/or atheist for whom fasting is a political act? Is it inevitable that for religious people, rituals such as fasting and prayer will always be intensely personal and private? Or is this division rather a consequence of our tendency to think of religion more generally as a private, personal affair, strictly separated from the public realm of politics?

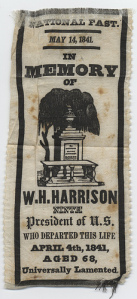

Let’s take a few examples of fasts that have overtly political implications. Aside from the example given by Marten last week, historically political leaders have called for national days of fasting and prayer at times of national crisis, or in memory of a fallen leader.[1]Other more contemporary examples include fasts from energy use, the annual World Vision 40 Hour Famine and the Global Poverty Project’s (GPP) Live Below the Line. The 40 Hour Famine involves going without food for 40 hours, while Live Below the Line involves participants spending only $2 a day (the globally recognized poverty live) on food. The 40 Hour Famine is promoted by a religious organization (though not as a religious act), while GPP is secular. But both fasts, for that is what they are, draw attention to the inequality and injustice that exists in our world whereby a vast majority of the global population exists on insufficient food.Unaccompanied by other religious rituals and disciplines such as prayer and worship, is it possible that these fasts could be religious as well as political? There will be a number of theological arguments against such a move. Christian theology, for one, argues that a fast must centre on God. “To use good things to our own ends is always the sign of false religion.”[2]But I don’t think this means that a fast that has political consequences is necessarily ungodly or unholy.

I want to suggest that actually it is possible for fasting, along with other religious rituals such as prayer, tithing and social outreach, to be both religious and political. In almost every religion, compassion for and solidarity with the poor is central.[3] Further, the major world religions hold that the Being they worship is fundamentally concerned with the rights and well-being of the poor. Thus, a fast undertaken to draw attention to and encourage action on behalf of those who do not have enough food is in line with the central tenets of most major faiths and consistent with the character of the deity that each faith worships.

I’m not trying to suggest that everyone who does the 40 Hour Famine or Live Below the Line is necessarily undertaking a religious act as well as a political act, particularly not those who are not religious. But it is difficult to deny that fasting has historically been a religious ritual, one that has powerful implications for the political realm as well. Fasting is a powerful witness, a declaration, if you will, that one is prepared to make sacrifices in order to see something changed.

The flipside of this, however, is that many religious people do not understand or perhaps appreciate the political implications that their fasting could have. Fasting is an important part of most spiritual traditions. There are a number of theological arguments and justifications for engaging in fasting. For some, fasting creates space in their lives for God to fill – by reducing the things we consume or focus on for sustenance, we open up ways for God to work and to show His power and also for God to speak and for us to hear. For others, it is a sign of joining in the suffering of their Lord – for Christians, who believe that Jesus gave up kingship in heaven to suffer an ignominious death on earth, this is particularly important. Still another reason is that fasting, like other spiritual rituals and disciplines, is powerful. When a believer chooses to fast, this act has implications in the heavenly realm and can have an impact for positive change in the spiritual life of the believer here on earth and in eternity.

But this is not, I suggest, limited just to the believer’s own life. Fasting and other spiritual acts like prayer, can in fact be effective forms of nonviolent protest. Along with the fasts mentioned above, hunger strikes are another powerful example of a fast undertaken for a political end. Turning to consider another ritual, prayer – A citizen who agrees to pray with an asylum seeker about their situation whilst visiting them in government detention is not just engaging in a religious ritual or an act of personal kindness, but is also performing a political act.[4] It is an inclusive action, assisting a formerly outcast individual to feel included, as well as indirectly challenging the government’s authority. As a member of the political community, the citizen challenges the boundaries of who does and does not belong by praying that, against the decision of the state, the asylum seeker will be recognized as a refugee and released from detention, thereby challenging the state’s right to say who can and cannot belong, who is and is not legitimate.

The thing that makes fasting, prayer or other religious rituals both religious and political is hope. Anyone who engages in a fast, from meat, from energy use, from food, for 40 hours, five days or 6 weeks does so because they hope that their actions will somehow produce transformative change, in their own lives or in the world around them, or both. In a time when politics seems dominated by cynicism and self-interest, hope is powerful. It’s also a way to do something. Whether we feel disempowered and marginalized by global economic and political structures, utterly insignificant in comparison to a divine deity, or simply overwhelmed and debilitated by the enormity of problems like global poverty, hunger, climate change, conflict, and the list goes on, actions such as fasting and praying, alongside others like marching or writing letters, enable us to restore some control and some hope to otherwise bleak and hopeless situations. In that sense, perhaps all political activism carries some spiritual dimensions, and all religious rituals carry some political implications… Thoughts?[5]

Erin Wilson is the Director of the Centre for Religion, Conflict and the Public Domain, Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Groningen .

[1] Examples include a national day of solemn prayer and fasting in the United Kingdom in 1756 because of a threatened invasion by the French, and national days of fasting and mourning in the United States for Presidents such as Abraham Lincoln and William Harrison.

[2] Richard Foster. 1998. Celebration of Discipline: The Path to Spiritual Growth. San Francisco: Harper Collins

[3] E.K. Wilson. “Beyond Dualism: Expanded Understandings of Religion and Global Justice” International Studies Quarterly vol. 54, no. 3 (2010), pp737-738

[4] Interview with B. Arthur, Brigidine Asylum Seeker Project, Melbourne, 10 September 2010

[5] I’m grateful to colleagues Matthew Tan and Samantha May who have both written pieces on prayer as political theory and zakat as nonviolent protest, respectively, which gave me much inspiration for this post. Both pieces have been prepared for submission to Religion, Politics and Ideology journal as part of a special issue on the blurring of the religious and the political in contemporary global politics.