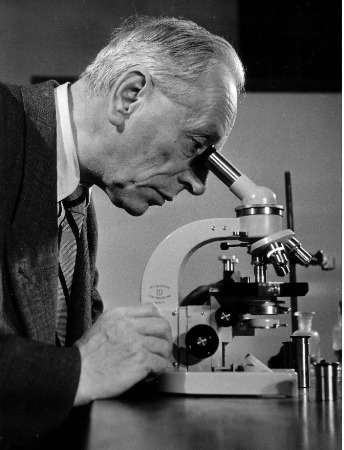

Colourful Characters: Frits Zernike

On 9 December 2025, it will have been exactly 400 years since Ubbo Emmius, the founder of the University of Groningen, passed away. In his tracks, various people who worked and studied there through the centuries made the UG a brighter place. Some of them have been exceptionally important, due to their remarkable achievements, ideas, and activities. This series sheds a light on some of these ‘Colourful Characters’. This week: Frits Zernike.

4 November 1953: Frits Zernike finds out that he has won the Nobel Prize in Physics

On 4 November 1953, Frits Zernike brought his ear close to the radio. A Swedish journalist had let him know that he might win the Nobel Prize for Physics. Professor Zernike had never thought he would ever be considered for such a high distinction. However, that turned out not to be true. His name resounded from the speaker. Shortly afterwards, he received an official telegram from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences: ‘The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has awarded you the Nobel Prize for Physics 1953. Letter follows. Westgren. Secretary.’

In the meantime, in another part of Groningen, a packed hall at the Stadsschouwburg was waiting for an opera performance to start. Suddenly, Rector Magnificus Pieter Jan van Winter took the stage to make an announcement: ‘Groningen has a Nobel Prize winner!’ A standing ovation followed.

Rum chocolates

The day after the announcement was made, Zernike intended to give his lecture, as usual on Thursdays, but things went a bit differently. At the Physics Laboratory on Westersingel, he was honoured by lecturers, students, and staff of the laboratory. As alcohol was not permitted in government buildings at the time, Zernike found a creative solution: he treated his colleagues and friends to... rum chocolates. On 10 December, he received the Prize in Stockholm. Above all, the international press wanted to know what he intended to do with the prize money. Would he buy a new bicycle? Zernike responded: ‘No, my good old bike holds up just fine.’ He spent part of the prize money to purchase several instruments that exceeded the University’s budget. Although the spotlight was not quite his natural place, he knew what was expected of him. Above all, he preferred simply getting on with his work.

An invisible life becomes visible

The essence of Zernike’s discoveries was unravelling the mysteries of living matter. In the academic world, the microscope was the most important instrument to study cells. However, the transparency of cells was a problem. Before Zernike’s discovery, cells would be killed and stained to be observed, making it almost impossible to study living matter. Zernike’s invention and development of the phase-contrast microscope made it possible to observe life processes such as nuclear division and cell division, and record them on film. In addition, Zernike had developed a version of the microscope that was affordable for any researcher, which led to it rapidly being used around the world. Zernike’s invention sparked a breakthrough in the medical and biological sciences.

Visiting Zeiss

When Zernike published his results for the first time in 1932, he received rather lukewarm responses. It is well known what happened during Zernike’s visit to the renowned company Zeiss in Jena, where he tried to present his discovery. Their response was: ‘If this had any practical value, we would have invented it ourselves long ago.’ After the war, it turned out that researchers in Jena had actually worked on the invention. Physicist Caroline Bleeker, who had an own optics and instrument firm, helped Zernike develop and build the new microscope.

Born in Amsterdam, matured in Groningen

Frits Zernike was born in 1888 into an Amsterdam family that was remarkable in many ways. His father and mother were both mathematicians. Frits’s older sister Anne was the first female theology student from Amsterdam. She later became the first practising female Dutch minister. His other sister Elisabeth was an award-winning literary writer. After HBS (Hogereburgerschool; the former Dutch secondary school for 12- to 18-year-olds), Zernike went to study chemistry at the University of Amsterdam. In 1913, he became assistant of the famous astronomer Jacobus Kapteyn in Groningen. He obtained his PhD in 1915 for his research into light scattering in gases and mixtures. Zernike then went to Groningen to work as a lecturer in theoretical physics. As early as 1920, he became a full professor in the same field.

Out-of-the-box thinker and experimenter

Zernike was a one-of-a-kind, multi-faceted physicist. Not only was he strong in theory, but he also knew how to apply that knowledge in practice. He specialized in improving physical instruments that others considered complete. He was an out-of-the-box thinker: not only noticing that something was not right but also asking himself why. In that regard, he was a true experimenter. His workspace in the laboratory on Westersingel was marked by sheer chaos: bottles, jars, screws, wires, and tools everywhere. Despite that, he always knew where things were. His intelligence and sharp memory served him well at a conference in Paris in 1946. He got stuck between two floors in the hotel elevator with several other conference attendees, Zernike looked at the control panel, saw which company produced the elevator, remembered the technical details of the mechanism, and, with a few manoeuvres, got the elevator moving again.

‘Did you know that you look like the Nobel Prize winner?’

He travelled to Stockholm, where, on 10 December 1953, he received the gold medal from King Gustaf. Of course, he was honoured, but it did not turn his world upside down. He went back by train. The story says that a man sitting across from him eventually remarked: ‘You look like the new Nobel Prize winner from the Netherlands.’ Zernike responded: ‘More people have said that.’

In 1958, he gave a farewell lecture in the Aula of the University of Groningen to mark his retirement. Zernike, who was considered a modest man, ended his speech by saying: ‘In this lecture, I wanted to show that my work has often led to unexpected results.’ Those remarkable ‘unexpected results’ still have a lasting impact on science. Starting in 1958, Frits Zernike was increasingly affected by a neurological disorder, which meant that he soon had to give up his work. He died in 1966 at the age of 77.

Frits Zernike in the city of Groningen today

The Zernike Campus is well known in Groningen, with its numerous academic and research buildings of the University of Groningen and Hanze UAS. The Zernike Campus also houses many companies. Groningen’s contribution to the national Weekend of Science, held every in October, is named after Frits Zernike: Zpannend Zernike.

Frits Zernike

-

1888: Born on 16 July in Amsterdam

-

1913: JC Kapteyn’s assistant at the University of Groningen

-

1915: PhD in chemistry, University of Amsterdam

-

1920: Appointed Professor of Theoretical Physics, Groningen

-

1953: Awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics on 4 November

-

1958: Frits Zernike retired

-

1966: Frits Zernike died on 10 March in Amersfoort

For more Colourful Characters, see the overview page.

More news

-

17 February 2026

The long search for new physics

-

10 February 2026

Why only a small number of planets are suitable for life