Aid: what works?

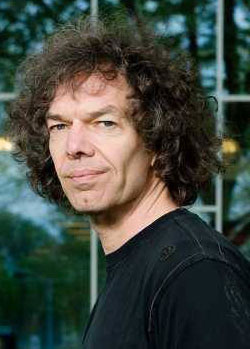

He just came back from Ghana – and if he could have been in two places at once, he would have been visiting a project in Malawi at the same time. Robert Lensink’s ambition is to help poor countries achieve greater prosperity. He is engaged in a tireless mission to find ways to help the world’s poorest inhabitants. ‘What works? As an academic, that’s the question you need to ask. And then you have to demonstrate the validity of your answer.’

Don’t be deceived: Robert Lensink is no ‘soft’ academic. He earned his stripes in the ‘hardcore’ world of cash flow, capital markets and insurance. And it is in insurance that he sees opportunities to reduce poverty in Africa and elsewhere. If, for example, you create an insurance for farmers that enables them to invest in new seed even after a failed harvest, they will be able to keep their businesses going.

Nor is Lensink a banker. In his roles as Professor of Finance and Financial Markets at the University of Groningen and Professor of Finance and Development at the University of Wageningen, he teaches, carries out research and supervises students. He is considered one of the best in his field and displays an extraordinary talent for motivating and inspiring students, generating money and delivering outstanding research. Earlier this year, he was appointed Officer of the Order of Orange-Nassau in recognition of his achievements.

Microfinance

Lensink knows better than most that capital flows and a decent banking system are of paramount importance for a country’s development. That was, after all, the field in which he obtained his doctorate. But even in countries with a robust financial system, the poorest people tend not to have access to it. Lensink is keen to find out what can be done to change the situation. Good access to sources of funding helps people to escape poverty. Microfinance (very small amounts – let’s say € 300 or € 1,000 per inhabitant) provides them with the leg up that they need. But because there are so many poor people, especially in Africa, that still adds up to vast sums of money in total.

Lensink speaks animatedly and passionately as he explains in clear terms why it is such a shame when a large section of a country’s inhabitants has no access to the banking sector. ‘These people are so poor that once they have harvested their crops, many of them are not able to save at all, so if they need to buy seed later in the season, there’s no money. Buying improved seed or fertilizer – which would be such a help to them – is completely out of the question.’

Excessively high rates of interest

Commercial banks don’t offer microcredit. ‘They are too far away to be able to evaluate the borrowers’ ability to repay their loans. And distance leads to high risk premiums.’ Aid organizations do want to invest in progress, but if all they do is to offer people microcredit, that won’t help tackle poverty. ‘The farmers don’t know the providers and don’t necessarily trust them, so they don’t save. Trying to interest them in insurance or a pension is trickier still, because most smallholders have no idea how such things work.’

Microcredit became something of a hype towards the end of the last century. In Bangladesh, Muhammed Yunus was awarded the Nobel Prize after founding the Grameen Bank especially for the country’s rural poor. Microcredit was promoted as a panacea for poor countries. Unfortunately, the concept was also exploited by parties pursing selfish ends. ‘You might remember the stories from Andra Pradesh in India about a whole series of suicides among the state’s poorest people because they were unable to repay loans to rogue institutions charging excessively high rates of interest.’ In the period that followed, microcredit was placed in an unfavourable light. ‘It went from being overestimated to being underestimated.’

Courses are vital

Lensink is researching the effectiveness of microcredit. Based on the results of multiple studies, he is now convinced that microcredit has the potential to improve the level of prosperity in poor communities. ‘Microfinance can definitely help combat poverty, but it is not the only tool available and its effectiveness does depend on certain conditions being met.’ He gives an example. The idea behind microcredit is that people invest the money they’ve borrowed into seed or equipment. But when people are in great need, it is very tempting to spend it on consumer items instead. ‘That’s why it’s good to not just offer people a loan but to combine that loan with a course.’

In the early days, microfinance was usually granted to groups – often groups of women in a village – in the belief that they would keep each other on track. Aid organizations have since abandoned that approach, and Lensink understands why. ‘We wouldn’t like it if our neighbours were given the job of checking up on how we run our household.’ And yet it remains true that group pressure sometimes leads to improvement. Take, for example, insurance against crop damage due to bad weather. It can be of great benefit to farmers, but obviously they need to have taken out the insurance beforehand. ‘Courses play a vital role in spurring people into action, since many poor farmers lack even the most basic knowledge. And if you can get villagers encouraging each other to take action, you’re really onto a winner.’

That’s why Lensink likes to work together with psychologists and other social scientists. ‘In one project, for example, we saw what happens if you make a short video in which a farmer from the village reports a better harvest as the result of having invested in improved seed and fertilizer. That gets people thinking. If other villagers respond by saying ‘I want that too’, so that the motivation is coming from them, your project has a high chance of succeeding.’ Another way of addressing farmers directly is to use text messages as a means of passing on tips about issues like the weather and the best time to harvest.

Make it a gift

'It often goes wrong when the organizations providing microcredit think that they need to pay their way. They say the market should do its work. But why? You can see microfinance as a leg up for the poor. Does it matter if there are costs involved? When an organization stops receiving subsidies, it targets less poor customers. Microcredit is, by definition, for the poorest of the poor. These types of programmes benefit not only the direct recipients but also the people around them. I don’t see the problem in making it a gift.’

The purpose of microfinance is to enable people to develop themselves. Lensink’s research helps chart whether the goals that were set have been reached. Whilst that’s useful and important, he does not immediately categorize those cases where the outcome is negative as a failure. ‘Of course you want to know whether the money has been used as you envisaged. But let’s say the farmers didn’t invest it but used it to buy food instead. Does that mean the project was a failure? Your money helped people through a difficult patch. Isn’t that also a form of welfare improvement?’

So what motivates this professor, and where does all that energy come from? ‘I think I’m quite idealistic. It’s so great when you get hold of a concept that actually works, that really helps people.’

CV

Robert Lensink (1962) studied economics in Groningen and obtained his PhD there in 1993 with a thesis entitled External finance and development. Since 2002, he has been Professor of Finance and Financial Markets at the University of Groningen and Professor of Finance and Development at the University of Wageningen. He is also scientific director of the Centre for International Banking, Insurance and Finance (CIBIF).

| Last modified: | 01 February 2023 4.20 p.m. |

More news

-

29 April 2024

Tactile sensors

Every two weeks, UG Makers puts the spotlight on a researcher who has created something tangible, ranging from homemade measuring equipment for academic research to small or larger products that can change our daily lives. That is how UG...

-

16 April 2024

UG signs Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information

In a significant stride toward advancing responsible research assessment and open science, the University of Groningen has officially signed the Barcelona Declaration on Open Research Information.

-

02 April 2024

Flying on wood dust

Every two weeks, UG Makers puts the spotlight on a researcher who has created something tangible, ranging from homemade measuring equipment for academic research to small or larger products that can change our daily lives. That is how UG...