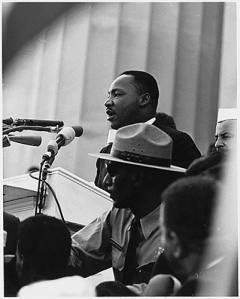

Order, justice and extremism: Martin Luther King, Jr and “Letter from Birmingham Jail” 50 years on

Fifty years ago today, Dr Martin Luther King, Jr. penned his now famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail”. On this anniversary, Erin Wilson reflects on what this important document can still teach us today.

On 16 April 1963, whilst imprisoned in Birmingham Alabama, Dr Martin Luther King Jr. responded to an open letter from some of his fellow clergy criticizing him and the civil rights movement. The clergymen urged King and his fellow civil rights activists to pursue negotiations and legal procedures rather than continue their nonviolent demonstrations and civil disobedience. They regarded King as an outsider causing trouble in Birmingham and argued that issues of racial injustice were best resolved in the courts, not in the streets. In effect, they were saying that to achieve justice, we must first uphold order.

King’s response, initially scribbled in the margins of a newspaper from his cell, is widely regarded as a core text for the theory and practice of social justice activism and the pursuit of nonviolent change. Letter from Birmingham Jail has been taught in political science courses around the world and has subsequently served as inspiration for nonviolent activists and religious adherents pursuing social justice. Justifying his involvement in Birmingham, though he himself was from Atlanta, Georgia, King wrote the now famous words: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” (1) Contrary to the view of the clergymen, King held that it was not possible to achieve social and political order at the expense of justice. For King, such “ ‘order’ is a negative peace which is the absence of tension.” Instead, he and other civil rights activists like him were pursuing a “positive peace, which is the presence of justice.” Justice should always have priority.

King’s letter is rich with detailed discussions of the insidious effects of segregation and discrimination and provides numerous insights that remain applicable today. Indeed, a church group in the United States has taken the opportunity of the 50th anniversary of Letter from Birmingham Jail to offer a response to the points King raised. Christian Churches Together in the USA (CCT) note that, despite desegregation and the Civil Rights Act, many of the issues King highlighted 50 years ago, particularly the emotional and psychological impacts of segregation, continue into the present (2). It is thought to be the first time that any group of clergy offered a response to King’s letter (3).

I recently re-read King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail whilst doing research into insurrectional politics (4). I was particularly struck by his discussion of extremism. The clergymen who penned the original open letter (one Catholic priest, 6 Protestants and a rabbi) accused King of being an extremist because of the relentless challenge the civil disobedience and protest he promoted caused to stable social and political order. King was initially uncomfortable with being cast in this light, but, as he explains in the letter, he eventually embraced it. His response is worth quoting at length:

“though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love: ‘Love your enemies, bless them that persecute you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.’ Was not Amos an extremist for justice: ‘Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.’ Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel: ‘I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.’ Was not Martin Luther an extremist: ‘Here I stand; I cannot do otherwise, so help me God.’ And John Bunyan: ‘I will stay in jail to the end of my days before I make a butchery of my conscience.’ And Abraham Lincoln: ‘This nation cannot survive half slave and half free.’ And Thomas Jefferson: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…’ So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists will we be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice? In that dramatic scene on Calvary’s hill three men were crucified. We must never forget that all three were crucified for the same crime – the crime of extremism. Two were extremists for immorality, and thus fell below their environment. The other, Jesus Christ, was an extremist for love, truth and goodness, and thereby rose above his environment. Perhaps the South, the nation and the world are in dire need of creative extremists.” (5)

Re-reading this letter 50 years on, this discussion of extremism is a timely reminder for us, living in an age where extremists, fundamentalists and rabble-rousers of every ilk are apparently around almost every corner. Contemporary nation-states, particularly in the West post-9/11, continually seem to be exploring how best to deal with “extremists”, both within their own borders and in the global community. The UK government, for example, last year published a policy document titled “Creating the conditions for integration”, the opening paragraphs of which argue that an integrated society “benefits us all” and “may be better equipped to reject extremism and marginalize extremists.” (6)

But what kind of extremists are we talking about? So often, particularly in politics, extremism is considered “bad” and associated with anti-democratic, exclusionary, discriminatory movements. Indeed, often it is used synonymously with “terrorism” (and, today, is almost invariably associated with Islam). Yet, as King notes, there have also been a plethora of other extremists, who have instead been extremists for justice, equality, and emancipation (7). It is not being an extremist that is necessarily bad, according to King, but the type of extremist that we are. Perhaps in contemporary politics, it may be more accurate to understand extremists as those individuals and groups that challenge established social and political order, which is not in and of itself a bad thing.

We must be careful not to assume that all those who challenge our established conventions and norms are necessarily “bad” or “wrong”, conservative, reactionary, violent and oppressive. After reading King’s letter, I could not help but wonder whom we, in our contemporary societies, may be classifying as “extremists” and subsequently disregarding. Is it possible that those we deem “extremists” may in fact be offering creative critiques of structures of injustice and oppression that our societies could benefit from? What King’s letter and indeed the civil rights movement as a whole show us is that our societies can benefit from encounters with extremists of all kinds, if we choose.

Let me make clear that I am not condoning or advocating violence or oppression. Extremist groups who pursue power for their own benefit and their own ends at the expense and exclusion of others should rightly be opposed. But the criticisms that they make of our own societies should not simply be dismissed out of hand. Instead of casting them as “bad”, or in some cases “evil”, and using this as a justification to ignore their criticisms, their antagonism to the way society is presently organized should cause us to at least pause and critically reflect on who may be excluded or oppressed as a result of our present social and political norms and structures. While the means such groups use or the additional claims they make may not promote justice and emancipation, their criticisms may nonetheless highlight existing injustices and inequalities in our own societies that we can and should then seek to address.

There are numerous examples of such “extremist” groups who test the boundaries of established political and social order. One can think of the “Battle of Seattle” in 2000 where “extremists” from the global justice movement protested outside the WTO meeting in an effort to highlight the detrimental impacts of neoliberalism. These protesters were deemed simply “anti-globalization” by their critics, offering little in the way of critique and alternatives other than a “superficial shopping list of complaints” (8). Yet, the global justice movement has produced innovative, creative, democratic and just alternatives to present marginalizing and impoverishing structures of neoliberal economics (9). Sea Shepherd is another example. Members of Sea Shepherd use direct action tactics to confront illegal fishing activities, occasionally facing armed threats from other boats (particularly Japanese whaling boats), and oppose over-fishing, whaling and other practices that threaten species with extinction (10). The No Borders network is yet another, working for the abolition of barriers to freedom of movement to enhance the rights of asylum seekers and irregular migrants (11). The Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, “long shunned as a collection of dangerous Islamist extremists” by Western powers (12), has also been a key provider of social services to the Egyptian poor, challenging the legitimacy of the authoritarian state and its neoliberal economic policies (13). Both Hamas and Hezbollah, also viewed as radical Islamist organisations by the West, at the same time provide critical social services to the poor and marginalized in their communities (14).

Extremists are always “unsafe” for established powers and always challenge existing power structures, but whether their challenge leads to more injustice, different kinds of injustice, or an end to injustice is not a predetermined outcome. The outcome depends on the type of extremism, but also on the type of response that is given to extremism. Perhaps, then, in addition to King’s question as to what type of extremists we will be, the question we also need to ask is not whether we respond to extremism, but what kind of response will we give? Will we give a response that is dismissive, closed, arrogant, unreflective and exclusionary, further entrenching the marginalization and division such “extremist” groups often feel to begin with? Or will we give a response that is engaged, thoughtful, humble, self-reflective, open and inclusive? Our responses will shape the type of society we build for the future.

Erin Wilson is the Director of the Centre for Religion, Conflict and the Public Domain, Faculty of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Groningen

(1) King Jr, Martin Luther. 1963. “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in Holmes, Robert L. 1990. Nonviolence in Theory and Practice. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, pp68

(2) Christian Churches Together in the USA. 2013. “A Response to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’.

(3) Banks, Adele M. 2013. “King’s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’ Response Arrives after 50 years’ The Huffington Post 13 April 2013. Available at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/04/13/kings-birmingham-jail-letter-response-arrives-after-50-years_n_3077933.html?utm_hp_ref=religion Accessed 14 April 2013

(4) Wilson, E.K. 2013. “Religion and Insurrectional Politics” Paper presented at the 54th Annual International Studies Association Convention, San Francisco, 3-6 April, 2013

(5) King Jr, Martin Luther. 1963. “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in Holmes, Robert L. 1990. Nonviolence in Theory and Practice. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, p74

(6) Department of Communities and Local Government. 2012. “Creating the conditions for integration” 21 February 2012. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/7504/2092103.pdf Accessed 15 April 2013

(7) King, “Letter from Birmingham Jail”, p74

(8)Steger, M.B., J. Goodman and E.K. Wilson. 2013. Justice Globalism: Ideology, Crises, Policy. London: Sage, p2-3

(9) Steger, M.B., J. Goodman and E.K. Wilson, Justice Globalism, esp Chapters 5-7

(10) http://www.seashepherd.org/

(12) Cohen, R. 2012. “Working with the Muslim Brotherhood” The New York Times, 22 October 2012. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/23/opinion/roger-cohen-working-with-the-muslim-brotherhood.html?_r=0 Accessed 16 April 2013

(13) Kassab, Elizabeth Suzanne. 2010. Contemporary Arab thought: cultural critique in comparative perspective. New York: Columbia University Press; Sadiki, Larbi. 2009. Rethinking Arab Democratization: Elections without Democracy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

(14) A.G. Grynkewich. 2008. “Welfare as Warfare: How violent non-state groups use social services to attack the state” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 31(4), pp360-363