Time for a new approach to hearing loss

With the help of a good dose of curiosity, Sonja Pyott is navigating her way through the complex world of our brain and our ears. On the journey to curing or improving hearing problems, she hopes to change some of our views on hearing health along the way.

Text: Nynke Broersma, Communication Office / Photos: Elmer Spaargaren

A big golden horn, which looks like it belongs to a turn-of-the-century phonograph or an obscure instrument, takes up a full corner. What is it doing in the office of a neurobiologist? ‘That is actually part of a phonograph; it was once part of auditory testing equipment’, Pyott explains, taking us back in time. ‘Of course, hearing equipment such as hearing aids have undergone improvements since then, but over the last 50 years the concept behind it hasn’t radically changed.’

It is time for a new approach to hearing loss, states Pyott. ‘We tend to accept hearing loss as something that just happens, like grey hair and wrinkles. But we have to change our mindset and realize that maybe we can do something about it!’

Destined

As the child of a mathematician and a psychologist, Pyott was almost destined to become an academic. The minute she starts talking about science, the thoughtful frown between her dark eyebrows disappears and her brown eyes light up. She thoroughly enjoys looking for new approaches to old problems. ‘It’s one thing to say: “I’m fascinated by the brain, I want to know how it works”, but how do we even go about studying it? Sometimes, you have so little to go on that you’re wondering where to even start. For me, that process is just very exciting!’

Lego bricks

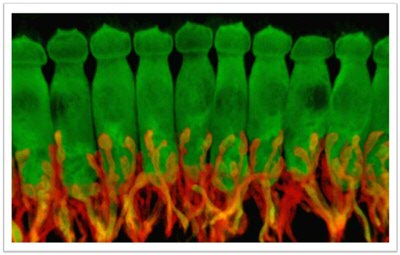

Pyott’s research focuses on the molecules in our inner ear. ‘You could consider molecules to be our building blocks – our Lego, if you will. They give all of the cells in our body a function, including the cells found in our inner ears that are necessary for hearing. We already know a lot about the broken Lego pieces linked to congenital deafness. Acquired hearing loss, on the other hand, is a lot more complex and a lot more prevalent. A number of Lego pieces are involved and they’re also influenced by environmental factors.’

Needle in a haystack

And so, Pyott and her colleagues are on a hunt for the molecules that play a role in acquired hearing loss. Recent work from her group identified over 14,000 molecules in the specialized sensory cells of the inner ear. ‘Taking a one-molecule-at-a-time approach is impossible. Therefore, we’re trying different approaches, such as comparing the molecules from younger and older animals to see what the differences are, which helps to prioritize molecules. It’s a bit like looking for a needle in a haystack, but we’ve found some promising candidates.’

Treating hearing loss pharmaceutically

Now that their molecular ‘inventory’ has given Pyott and her team a good sense of direction, they’re continuing their research with the hope of developing pharmaceutical treatments for hearing loss. Pharmaceutical companies have shown a growing interest in drugs to prevent – and hopefully reverse – hearing loss but very few drugs are used in clinical trials. ‘Drugs target molecules, the Lego pieces’, Pyott explains. ‘If we don’t know the full molecular repertoire, then we don’t know which drugs to develop. So, having this molecular inventory is essential.’

The odd workings of the brain

Even after years of studying neurobiology, Pyott is still amazed and puzzled by the brain. This becomes particularly clear when she talks about tinnitus. People with tinnitus hear phantom sounds, usually sounds that are unpleasant, like ringing or buzzing noises. ‘One of the theories behind tinnitus is that, in some people, the brain fails to adapt to hearing loss. The lack of input is somehow filled in by the brain.’ Similar to feeling pain in an amputated arm? ‘Exactly! And I just found out about this but a small group of people who’ve lost their sense of smell experience ‘phantosmia’, or phantom smells. They are usually unpleasant, described as something burnt or rotten, just as tinnitus is often an unpleasant sound. Isn’t it odd how the brain works?’

Tinnitus research

As a member of research consortium TIN-ACT, Pyott and researchers from all over Europe are joining forces to study tinnitus. ‘There’s still a lot of uncertainty about where in the brain tinnitus arises and why tinnitus varies between one patient and another. While excellent work has been done already, we still need to fill in the gaps. One of the things we hope to do with TIN-ACT is to unite researchers – especially researchers using animal models and those working with patients – to get a fuller picture of the causes and possible treatments.’

Quality of life

Today, Pyott is more satisfied than ever with her choice to work in this field. ‘These are exciting times for auditory research. We’re starting to realize that improving our hearing health might be the biggest way that we can influence healthy ageing. Recent studies have shown that hearing loss is linked to cardiovascular diseases, dementia, diabetes and a range of other diseases. It’s still a chicken and egg situation but it’s interesting that this is being studied now. If I really want to make an impact on the quality of life – and not just the quantity – then I’ve picked the right field!’

Fashion statement

Do you have hearing loss? It is common to connect this with getting old, losing your memory and probably not being as sharp anymore. Many people feel that their hearing loss is something to hide and that their hearing aids should be as invisible as possible. Pyott is well aware that there are still stigmas attached to hearing loss but she hopes and thinks that our attitude will change. ‘When I was younger, you did not want to be the kid wearing glasses. Now, glasses have become a fashion statement and most of us regularly get our eyes checked. But when was the last time you had your hearing checked?’ If it were up to Pyott, getting a hearing test would be added to the list of having your blood pressure, heart rate or vision checked – all things that we now consider ordinary aspects of caring for our overall health.

Beyond the research lab

Pyott is also very busy outside the laboratory. She is involved in pre-medical and graduate teaching and is currently chair of the Young Academy Groningen (YAG), an organization for talented early-career researchers. Among other initiatives, YAG has organized and contributed to a number of public outreach events, including Noorderzon performing arts festival and Zpannend Zernike science festival. Pyott: ‘The research that we’re doing at the University is great and we need to communicate this more to others, especially to the people that our research impacts’.

What she wants the public to know about hearing loss comes across loud and clear: ‘Your hearing health is absolutely important!’

More information

- Contact: Sonja Pyott

- Young Academy Groningen

More news

-

17 November 2025

Artificial intelligence in healthcare

-

04 November 2025

AI Factory in Groningen advances digital sovereignty

-

03 November 2025

Menopause in perspective: How the media influences our perception