The search for extraterrestrial life inspires and humbles us

The photo on the side has become known as the Pale Blue Dot. It was taken in 1990 by NASA’s Voyager spacecraft from a distance of 6 billion kilometres from Earth. Our planet floats in an almost infinite void in the universe and, as far as we know, is the only planet on which life exists. Floris van der Tak, senior scientist at SRON and Professor of Astrochemistry in Groningen, is searching for life beyond our planet.

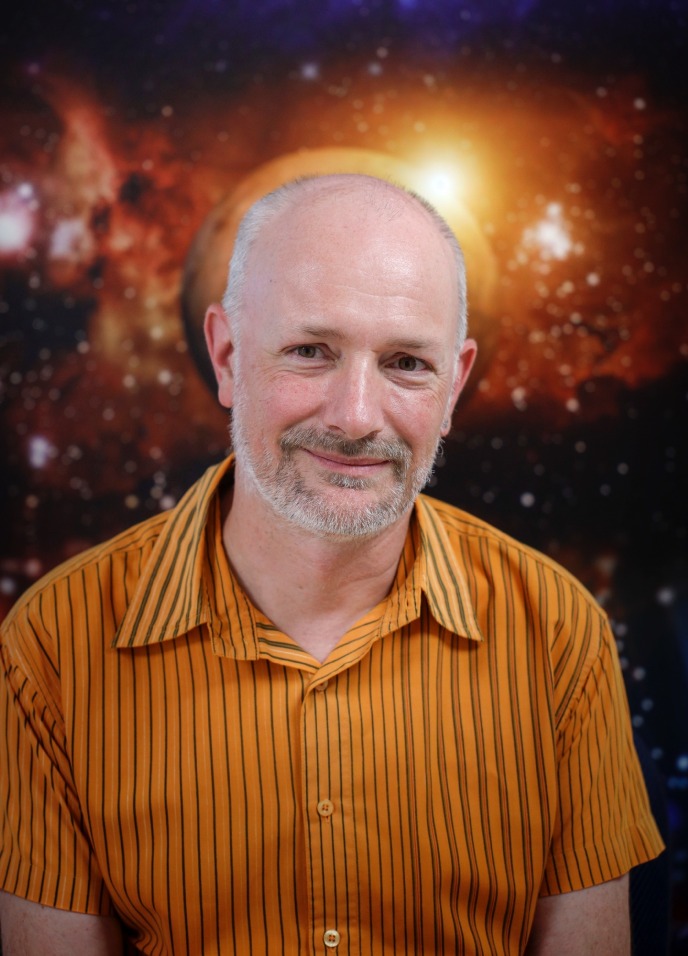

Text: Jaap Ploeger, Corporate Communication UG / Photos: Henk Veenstra

‘Our search for extraterrestrial life teaches us a lot about our place in the universe,’ says Van der Tak. ‘Everything remains far away, so we have to rely on ourselves. The Pale Blue Dot reminds us that we are just a tiny speck and that, for now, we cannot survive beyond Earth. There is no one out there to help us if things go wrong. On the other hand, it is unlikely that Earth is the only place where life has originated.

What is extraterrestrial life?

When asked what extraterrestrial life is, Van der Tak admits: ‘We don’t exactly know. We really only have our own earthly life forms as a frame of reference. So that’s where the search begins. That doesn’t rule out the possibility that completely different forms of life have emerged in the universe, but we’re best off looking for what we know.’ The life Van der Tak is looking for is not necessarily intelligent. It could be bacteria, single-celled organisms, or microbes. To find them, he searches for specific gases in the atmospheres of planets outside our solar system, known as exoplanets. If the building blocks or waste products of life are detected in those atmospheres, it may indicate that life has originated on that planet. ‘For 90% of its existence, our Earth was inhabited exclusively by single-celled organisms, so there is a good chance that we will find a planet where life has not yet evolved any further, if that happens at all.’

Recently, there was a lot of excitement about a possible trace of life on exoplanet K2-18b, about 120 light years away. Traces of dimethyl sulphide, molecules that on Earth are only produced by plankton, were discovered in the atmosphere of this planet. ‘In hindsight, that announcement was far too premature,’ Van der Tak sighs. 'The data were misinterpreted, which led to hasty conclusions. That’s not helpful for our field. On the other hand, as a scientist, you cannot always wait until you are 99.99% certain.' It does illustrate how extraordinary it would be if extraterrestrial life were actually found, and therefore how challenging it is to discover.

Earth is (not) unique

It has only been known since the 1990s, through observations, that planets orbit other stars. And since then, the prevailing view has been that every star has one or more planets. This raises the question: where is everyone? There are many explanations for this Fermi Paradox, the paradox that we find so little other life in an infinite universe,’ says Van der Tak. 'It’s very likely that life has originated somewhere else. But just like on Earth, that life must have existed for a certain amount of time. On Earth, it has existed for almost four billion years. And although our planet is not unique, it is perhaps quite remarkable that life has not yet gone extinct. We have also survived several mass extinctions on Earth, which may have marked the end of life elsewhere in the universe, possibly on Mars, for example. We know that rivers and oceans once flowed there, possibly with life. But something happened that made the planet dry and uninhabitable.'

Life can also develop beneath the surface of a planet or moon, which makes it more difficult to detect. Carbon and hydrogen compounds have been found in the gas plumes from geysers at the south pole of Saturn's icy moon Enceladus. On Earth, organisms live in similar conditions near undersea geysers. And Jupiter’s moon Europa has an ocean beneath its kilometre-thick layer of ice, and that ocean is warm enough for organisms to survive.

Missions

In addition to analysing data from space telescopes that search for habitable planets, Van der Tak is also involved in the development of those telescopes. 'Together with colleagues, I determine what we want the telescope to be able to observe, for example in the infra-red spectrum,’ says Van der Tak. Next year, ESA will launch the PLATO (PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars) space telescope, which will study rocky exoplanets, such as Earth, orbiting sun-like stars. My institute, SRON, is closely involved in this project.'

Many more projects are planned for the coming decades. In 2029, ESA’s ARIEL mission (Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey) will be launched into space to map the atmospheres and cloud cover of thousands of exoplanets simultaneously. NASA is planning to launch the Habitable Worlds telescope in the 2040s-2050s, which will specifically focus on searching for signs of life on other planets. At the same time, Europe will be launching the LIFE (Large Interferometer For Exoplanets) mission, which will measure mid-infra-red spectra of Earth-like exoplanets. These data could very well contain evidence of life. Institutes in Leiden, Dwingeloo, and Groningen are involved in the development of LIFE, with Van der Tak taking a leading role.

We live on a fragile crust

According to Van der Tak, the fact that the search for life continues underscores the importance of preserving life. Earth is a small, modest planet at exactly the right distance from the Sun, which makes life possible. Yet that life and ecosystem are limited to a wafer-thin layer of about one to one and a half kilometres, while our planet's diameter is approximately 6,000 kilometres.

Van der Tak: ‘The habitable crust and all its biodiversity are naturally very vulnerable, due to influences from within but also from outside, such as meteorites. This is where Fermi comes into play again. Although life may be able to arise anywhere, can a biodiverse ecosystem that sustains itself also emerge? On Earth, humans are a very vulnerable species that are completely dependent on a well-functioning ecosystem. We cannot even produce energy ourselves through photosynthesis and need plants for food. Speaking of which, surely that should give us food for thought about how we treat our planet.

More information

More news

-

06 January 2026

Getting to grips with the workhorses of our body