People will always be needed

Writers, journalists, legal professionals, programmers, composers... If we are to believe the media, AI will make these and many more jobs obsolete in the near future. Professor Ana Guerberof Arenas has her doubts, at least when it comes to her own field: translation. ‘It is great to have Google Translate at hand if you need to book a hotel in Russia. But when it comes to Tolstoy, you'd rather read a beautiful literary translation. That's where humans do better.’

Text: Helma Erkelens / Photos: Henk Veenstra

Ana Guerberof Arenas, Professor of Translation and Technology at the Faculty of Arts, is not opposed to machine translation (MT), but she believes it should not be used without careful consideration. ‘The application has to be appropriate.’ That word comes up frequently during the interview. AI translates it into Dutch as “gepast” or “geschikt”, which is indeed accurate in this context. But nothing more. What does appropriate actually mean?

The world behind words

Guerberof Arenas explains that it is the complex world behind the words that

makes a translation appropriate. This includes factors such as purpose, target group, sender and receiver, emotion, living environment, perceptions, and culture — when a translator can sense this world, the reader can connect with the text. ‘This requires a high level of translation skill, knowledge, and empathy — something that only top human translators are capable of.'

People will always be needed

Machine translation will undoubtedly come close, but human translators will

always be needed, and not only when it comes to literature, she says. For instance, machine translation also has its limitations when it comes to communication with authorities. ‘A doctor who suspects a major medical problem, is not going to rely solely on Google Translate. They want an interpreter— a human being, that is.’

Big money

However, the pressure to use translation software is strong. ‘It's the world of big money.’ Companies that develop these translation tools — such as Open AI, Google and Amazon — show us that it works if you exactly know what you are looking for. As a result, people are quick to conclude that machine translations can be used anytime and anywhere, but it's not that simple.'

Looking for proof of usefulness

To counteract the AI hype, scientific evidence is needed to determine when and how MT can best be used. That is the research focus of Guerberof Arenas. She researches, for example, how readers connect with an MT text compared to a human translation, without knowing in advance how the text was produced. Connection relates to the level of understanding and recognition. ‘We use an eye tracker to measure eye movements during reading, which shows that people fixate on the content they feel connected with. We use questionnaires to find out what participants feel connected with. We notice that people fixate a lot less on machine translations, not only because they sometimes struggle to understand them, but mainly because they feel little or no connection to them. They either barely identify with these translations or not at all.'

Research into the creativity of computers

Creativity is what makes humans unique, but AI believers claim that computer-generated translations can be just as creative. Guerberof Arenas has shown that this is not the case: human translators have a higher level of creativity. In her research, participants were given three translations of a novel by Kurt Vonnegut from English into Catalan and Dutch: a human translation, an MT, and a combination of both. ‘The human translation scored significantly higher on creativity. This makes sense, as a neural MT-system trained on literary data can only offer literal solutions for terms that are difficult to translate, which often leads to incomprehensible translations. Research also shows that using machine translation as the basis for post-editing results in translations that are too poor to be published.’

The profession needs to stay interesting

Guerberof Arenas believes it is important that publishers, media, and large companies continue to invest in improving MT, but also in human translations, if only to maintain the quality of MT output. That is why the translator's profession needs to stay interesting. ‘Top translators are not particularly eager to correct poor machine translations; it brings absolutely no job satisfaction. And certainly not when companies want to pay even less for a translation because of MT — the rates were already shockingly low. Therefore, there's a risk that no one will want to become a translator anymore.’ This raises the question of how to keep the profession interesting for students. ‘I do not have an immediate answer, but I think we should aim for a good balance between human and technical aspects. And of course, recognition and decent compensation.’

A new type of translation professionals

The Master's programme in Translation and Technology also has to ensure an appropriate use of MT. This programme will launch in the academic year 2026-2027. ‘We need translation professionals who speak the language of AI. Who know its potential and limitations, as well as the essence of the translation profession. Who can engage in informed dialogue with companies. Who can say: I have studied these languages, but I also know how large language models work. I work with computer-assisted translation, with tools, and with MT. I can tell you when it is useful and when it is not, and also explain why it doesn't work in a particular situation.’ This Master's degree programme welcomes students from the humanities, science, and social sciences who wish to become a translator in their field. ‘That means it is also a suitable option for medical students who do not want to become doctors, but who do want to translate medical texts.’

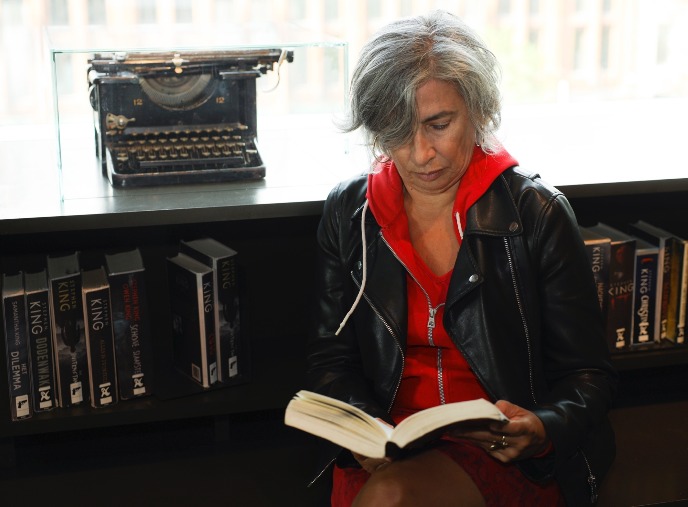

Ana Guerberof Arenas and the Aletta Jacobs chair

Ana Guerberof Arenas has been appointed to an Aletta Jacobs chair. Born in Argentina and raised in Spain, she had never heard of Aletta Jacobs, the first female student at a university in the Netherlands. She has now read up on her. ‘An incredibly visionary woman, who did not care about what others thought of her. I think we need that now. We need people who think outside the box and go against the grain. There's less and less space for science in general, and for the humanities in particular. There's less and less compassion and solidarity.’

Guerberof Arenas is known for her independent spirit. Not only did she make the definitive transition to academia at the age of 50, after a long career in the translation industry — unusually late — but she already held a PhD by then. She was already interested in researching the importance of MT for translators at a time when everyone still dismissed Google Translate as wildly inaccurate. ‘But I saw the machine translations of software and other technical texts improve little by little each time. Those texts have a fixed structure and a lot of repetition. MT performs well on texts like that. Nowadays, MT is fully integrated into technical translation.’

Guerberof Arenas will update the Master's programme at the UG and lead research into the creative process of literary and audiovisual translators. The research is part of the EU Consolidator Grant project INCREC.

More information

-

Want to know more about AI? Read Autonomous systems should be fairer and more democratic.

More news

-

07 January 2026

How music is helping to revive the Gronings dialect

-

16 December 2025

How AI can help people with language impairments find their speech

-

18 November 2025

What about the wife beater? How language reinforces harmful ideas