Margriet Hoogvliet: ‘Even poor people read the Bible in the Middle Ages’

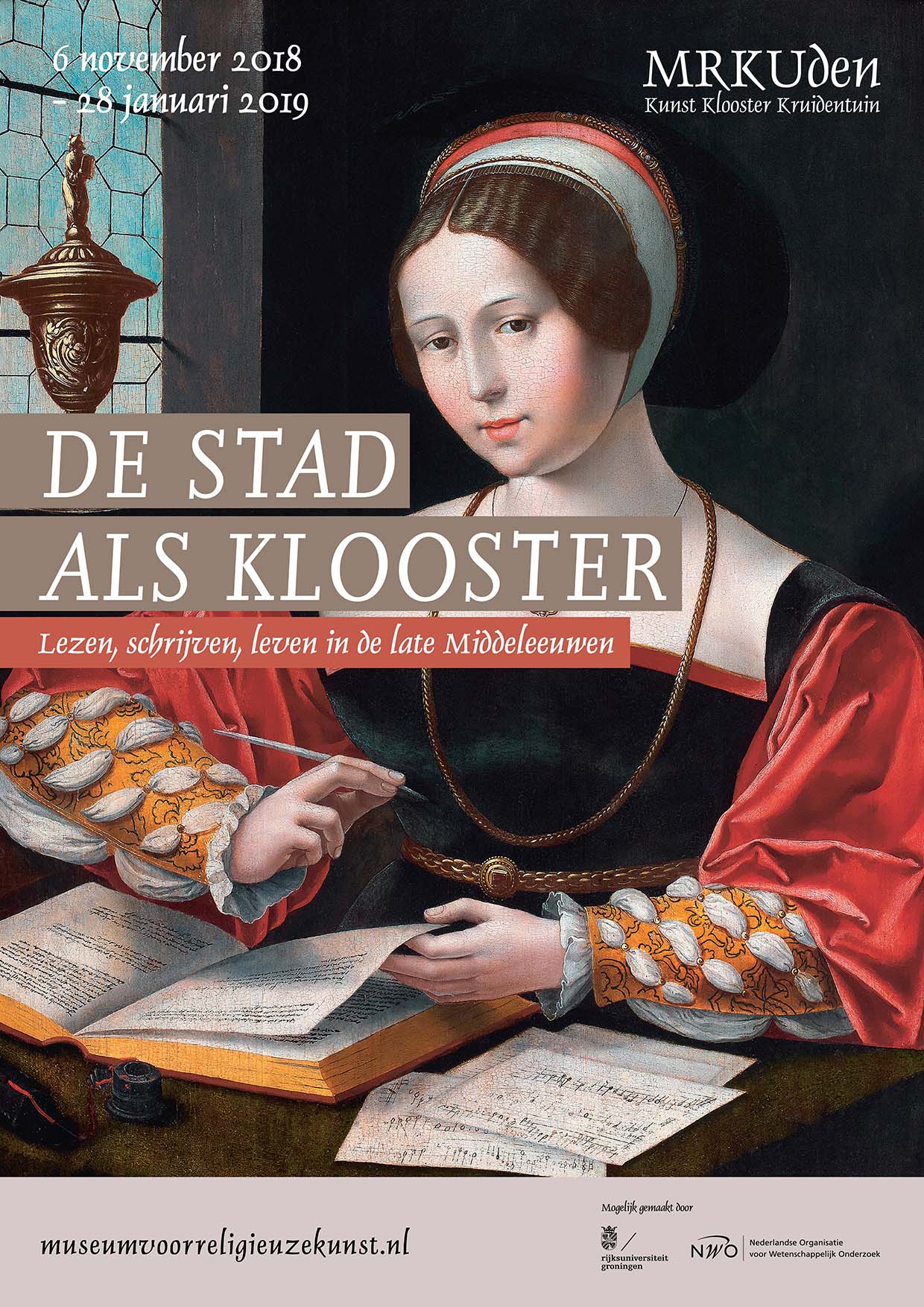

It has been revealed that people in the Middle Ages read more religious texts than we previously assumed. These are the findings from research carried out by Margriet Hoogvliet (54) and her colleagues, who are studying the religious reading and writing culture of urban populations between 1400 and 1550. The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) Cities of Readers project is organising an exhibition entitled De Stad als Klooster (exhibition) (The City as a Monastery) to present the results of the research. The exhibition will open on 6 November in the Museum voor Religieuze Kunst in Uden, in the province of North Brabant. For her work, Hoogvliet has not only journeyed through history, but also through various European countries. Her curiosity took her to France, the United Kingdom and sometimes even further, where she studied the old manuscripts, wills, estate inventories and other material that will be on display in the exhibition.

Text: Bineke Bansema, Communication/UG, photo: Hesterliena Wolthuis

‘Citizens in the Middle Ages were active readers and writers of religious texts. They read the same spiritual manuscripts as monks and alternated their working activities with prayer and devotion. So, contrary to what we often think, reading the Bible was not just an activity for the elite,’ says Hoogvliet. This mainly applied to people living in towns, who combined manual labour, trade and family life with religious reading and writing. Leading an active working and family life was increasingly seen on a par with a life of contemplation in a monastery.

Widow

Even many of the poorer citizens were literate. Hoogvliet explains about the legacy of an old widow in the French city of Amiens. ‘I study archive documents, such as estate inventories. During my research, I came across the inventory of a widow from a deprived area. There were four pages, which doesn’t sound like much, but among her belongings was a Bible. It was old, dirty and worn-out. In other words - well used. We don't know how she managed to own a Bible. She might have bought it at a second-hand book market, but it could have been a gift from a wealthy benefactor. It was quite common for the rich to leave Bibles to the poor. Servants often inherited enough money to send their children to school.’

Amiens

Hoogvliet studied old manuscripts in libraries in Paris and London and spent a lot of time researching in archives. Amiens in the north of France is one of the places she worked in. Although much of this Mediaeval city was destroyed in World War I and II, the municipal archives remained. Hoogvliet drove there from her home town of Hattem on many occasions. ‘It’s a difficult journey by train as wherever you go in France, you always have to change in Paris. I book a cheap hotel in Amiens and drive back a few days later. We try to do everything as cheaply as possible so as not to squander the project budget.’

The Stad als Klooster exhibition

Over the past few months, Hoogvliet has been concentrating on compiling and setting up an exhibition entitled De Stad als Klooster – Lezen, schrijven, leven in de late middeleeuwen (The City as a Monastery - reading, writing and life in the late Middle Ages), in the Museum voor Religieuze Kunsten (Museum of Religious Art) in Uden. It is proving to be great fun, and a learning experience for both parties. Hoogvliet: ‘A project like this has really taught me a lot. Both sides have to make concessions. The museum wants as little text as possible in the exhibition, so we have to squeeze all our knowledge into eighty words. This doesn't always work. Visiting a museum is supposed to be an experience; it should involve more than just looking at books in display cabinets. The end result is an interactive exhibition featuring unique art and artefacts and Mediaeval manuscripts. There are all sorts of things for visitors to do, including listening to liturgical music in French, calligraphy in the writing studio, learning to use a rosary and going on a virtual pilgrimage.’

Augmented reality

After this project, Hoogvliet plans to continue her work in Tours and Orléans. Compiling the exhibition has taken a lot of time, time she would otherwise have spent on research. Having said this, Hoogvliet is keen to do something similar again. Devising a series of lectures for a MOOC, for example. To her mind, teaching is one of the most socially relevant aspects of Arts research. She's already got an idea for her research in Orléans: she will use augmented reality to show tourists walking around the city where and how a hosier lived five centuries ago, and how he read his book about the Life of Christ at home with his family. She thinks that this will be an interesting project and will go and talk to the local tourist information office about it when she gets there.

Job hopper

Hoogvliet isn't worried about not having a permanent job, although she knows this would be a horror scenario for some people. At present, she has a four-year appointment as a postdoc researcher for the ‘Cities of Readers’ project in the Faculty of Arts at the UG. ‘I hadn’t realized just how much I enjoy getting to grips with new things. It keeps me on my toes.’ As you can tell from her CV, Hoogvliet is a job hopper: a year in Leeds, a month at the Sorbonne, 12-month contracts in Amsterdam, Utrecht, Groningen. She works as a university researcher or lecturer in most of her appointments. The only permanent job she had was as a policy advisor, but she left to resume research. As from next June, she will start working on a research project in France for which she was awarded a prestigious grant. Her 15-year-old daughter Sophie will accompany her and spend a year at a French school. ‘She might lose a year of Dutch schooling, but I'm sure this will be a wonderful experience.’

In 2014, the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) allocated € 750,000 to the 'Cities of Readers: Religious Literacies in the Long Fifteenth Century’ project. Professor Sabrina Corbellini and Professor Bart Ramakers from the Faculty of Arts are heading the project group alongside Margriet Hoogvliet. Two PhD candidates are conducting PhD research as part of the project. The ‘De Stad als Klooster’ exhibition (from 6 November in MRK in Uden) was included in the project proposal as an outreach activity.

More information

- Margriet Hoogvliet

- De Stad als Klooster (exhibition)

- Cities of Readers

| Last modified: | 04 October 2022 11.05 a.m. |

More news

-

23 April 2024

Studying depopulation also means studying the history of those who stay

Assistant professor Yuliya Hilevych from the Faculty of Arts researches regional depopulation in the Netherlands, Finland, and Ukraine by placing the phenomenon in a social-historical perspective.

-

22 April 2024

Trump or no trump, that is the question

UG researchers Ritumbra Manuvie, Pieter de Wilde, and Lisa Gaufman look ahead to the elections in India, Europe, and the United States, respectively. This week: Lisa Gaufman.

-

15 April 2024

‘The European elections will be as boring as always’

UG researchers Ritumbra Manuvie, Pieter de Wilde, and Lisa Gaufman look ahead to the elections in India, Europe, and the United States, respectively. This week: Pieter de Wilde. He predicts that the European elections will be as boring as always.