Global shortage of agricultural land in 2050

In the coming decades the world will face the challenge of how to produce enough food with limited agricultural land and an increasing population. This will only be possible if intensive agriculture and fertilizer are used. This is what environmental scientist María José Ibarrola Rivas has concluded in her PhD thesis. Ibarrola Rivas calculated that a Western diet needs four times as much fertilizer than a simple diet does. She will defend her thesis at the University of Groningen on 1 May 2015.

Scientists regularly try to make predictions about population growth or the environment or the economy. ‘I combined these studies’, says Ibarrola Rivas. ‘And I only looked at the facts in my research. It is the job of local policymakers to find solutions.’

Developing countries

‘The population of poorer countries in particular is set to increase, and this is where the greatest change in eating habits is occurring. This means that much more land will be required in future to produce food. In 2050 about 70% of the world’s population will live in areas with a very limited amount of agricultural land, particularly in developing countries. Only if they make very intensive use of fertilzers will they be able to meet the food needs of the population,’ says Ibarrola Rivas. ‘This will have a considerable effect on the environment in these regions.’

Available land

For her research, Ibarrola Rivas divided the world into different regions, and made a distinction between poor regions (many countries in Africa, for instance), regions of average prosperity (such as China) and rich regions (such as Western Europe). She first looked at the availability of agricultural land and water for the production of food. ‘The differences between the regions are enormous. In some areas more than 5000 square metres of agricultural land is available per person, whereas in others it is less than 1000’, she says.

Trade in Western food

‘In 2050 some 70% of the world’s population will live in areas with less than 1000 square metres of land available per person’, Ibarrola Rivas continues. As agricultural land cannot be moved, she expects a flourishing trade to develop in food between the rich West and developing countries.

Need for fertilizer

Ibarrola Rivas went on to study eating habits in various regions. The populations of developing countries tend to eat a simple diet: grains, pulses and root vegetables. The diet in Western countries comprises food such as meat, dairy and oils. Somewhere in between is what is called the transition diet, in which people eat a limited amount of meat. Ibarrola Rivas calculated that four times as much fertilizer is needed for a Western diet than for a simple diet.

Change in diet

Ibarrola Rivas studied changes in eating habits in the world in order to be able to predict how much agricultural land and fertilizer will be needed in 2050. ‘Generally speaking, non-rich countries are moving towards the Western diet with lots of animal products, but they do still stick very much to their own eating habits. For instance, the Chinese are mainly eating more pork, whereas it is the consumption of beef that is increasing in Latin America and people are eating more and more chicken in Northern Europe and Northern America.’

These differences are relevant to how much agricultural land will actually be needed. ‘With each farming method – for example, intensive or organic – you see that much more agricultural land is needed to produce beef and milk than to produce pork and chicken. Beef and milk production result in much higher greenhouse gas emissions too.’

Regional solutions

Ibarrola Rivas’s research clearly exposes a future global problem: ‘There is no single country that can produce enough food for the local diet without the use of fertilizer. Environmental scientists are already worried about excessive use of fertilizer and are looking for ways to reduce it, but population growth and changes in diet are making increasing amounts of fertilizer necessary.’ There is no single global solution, says Ibarrola Rivas. ‘As each region has its own diet, each region also faces its own challenges. The solution must therefore be conceived at the regional level.’

Curriculum vitae

María José Ibarrola Rivas (1983) was born in Mexico City. After completing her Bachelor’s degree in Physics Engineering, she went on to complete a Master’s degree in Energy and Environmental Sciences at the University of Groningen in 2010. She then began her PhD research in the Center for Energy and Environmental Sciences (IVEM) research group at the Energy and Sustainability Research Institute Groningen (ESRIG). The research was funded by CONACYT and Erasmus Mundus.

Note to the editors

· María Ibarrola Rivas will defend her thesis at the University of Groningen on 1 May 2015. The title of the thesis is: The uses of agricultural resources for global food supply - Understanding its dynamics and regional diversity ;

· For further information, please contact the Secretariat of the Center for Energy and Environmental Sciences (IVEM) , tel. +31 (0)50 363 4609 or Ibarrola Rivas’s co-supervisor Dr Sanderine Nonhebel, tel. +31 (0)50 363 4611.

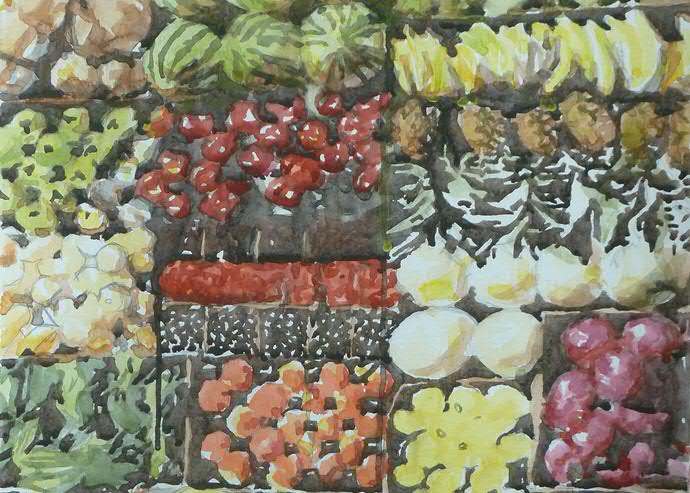

· Illustration: Julio Pastor ( www.juliopastor.com )

More news

-

17 February 2026

The long search for new physics

-

10 February 2026

Why only a small number of planets are suitable for life