Will the lockdowns cause baby booms? A demographer's view on the pandemic.

This blog post was originally posted on 11 December 2020 on the MindMint website.

Credit blog image: www.vperemen.com

The coronavirus that is currently pestering our precious world is first and foremost a health issue. Researchers in the field of medical sciences have thus been entrusted with finding a vaccine against the virus and mitigate further incidence of disease. But what can be learnt about this pandemic from researchers in other fields of science? In this piece, Jonne explores what the field of Demography can tell us about the pandemic thus far and speculates what its effects may be for future studies of social sciences.

What do demographers study?

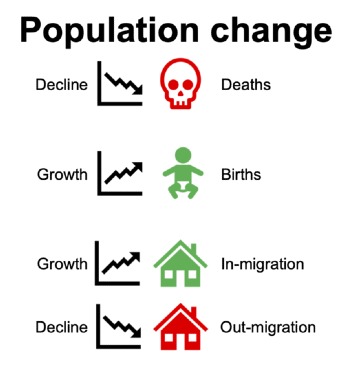

Demographers study population stability and population change. A population, here, refers to a group of humans living within a given local, regional, or national area. It is fun to realize that the size of a population only changes because of three simple mechanisms: a population shrinks when people pass away, it grows when babies are born into it, and it can either grow or shrink due to people moving in or out. Therefore, the three processes most focused on by Demographers are: mortality, fertility, and migration as well as the balances between the three processes.

What can demographers tell us about the effects of the pandemic?

MORTALITY: death as a positive motivation tool?

In the spring of 2020, while SARS-CoV-2 was spreading across the world, it became clear that older people and those with pre-existing conditions were especially vulnerable for infection. Further, the likelihood of dying from an infection with the virus increases exponentially with age, yet everyone can contract and spread the virus equally. From a psychological perspective, the fact that simply visiting or touching our dearest family members may be a harmful exchange with deadly consequences lead to heightened mortality awareness.

Mortality awareness is the realization that we are all going to die one day. This realization has been relatively absent from the lives of people who have lived in countries that are at peace and provide sufficient health care. Demographers and other social scientists may be able to shed some light on what this newfound mortality awareness might bring about in people’s lives. In the literature, three distinct answers are put forward:

-

The ‘terror management theory’ is one of the more traditional views on mortality awareness. It would suggest that people will experience increasingly negative thoughts during the pandemic, which may lead to feelings of fear and anxiety.

-

A more positive view on mortality awareness comes from the ‘post-traumatic growth’ literature. Here, scientists suggest that people are capable of growing emotionally strong and making positive changes in their lives after going through stressful or challenging situations, such as the pandemic.

-

Finally, there is empirical evidence that suggests that going through a major crisis heightens people’s ‘mortality legacy awareness’, which can lead to people wanting to leave something meaningful behind after they are gone. Interestingly, people with a heightened ‘mortality legacy awareness’ may use the realization that we are all going to die one day as an important motivational tool to care about staying healthy, finding spiritual growth, work on art projects, provide service to others and start a family.

FERTILITY: will the lockdowns cause baby booms?

Starting a family and carrying on a family history are two important ways that can make people feel like they are leaving behind a meaningful legacy. That, coupled with being locked inside your house for extended periods of time may be the perfect recipe for a baby boom, right?

According to demographers, it may not be that straightforward. Initially, some people may have been eager to “make some babies” during the first lockdowns. We could thus expect a tiny baby boom at the end of 2020 and the beginning of 2021. However, a recent study has shown a negative effect of the pandemic on the fertility intentions among 18-to-34-year olds in Italy, Germany, France, Spain, and the UK. This is also what the evidence from previous pandemics would leave us to conclude, namely: an initial decline in fertility rates during the pandemic and then an acceleration in fertility right after the pandemic is over. This means that births decrease at first, but then balance out again due to the peak that comes once the ‘crisis’ is over.

Regarding the current pandemic, demographers expect birth rates to fluctuate depending on the severity of pandemic’s threats. So, whenever the threats were low, people may have wanted to start a family regardless of the pandemic. However, once the pandemic started showing signs of a ‘long breath’, less people may have been inclined to add new-borns to their households. Especially because hospitals were overcrowded and family and friends could not visit to help with infant-care. Finally, 9 months after the more severe threats of the pandemic start to fade again, we may see a tiny baby boom again.

MIGRATION: limiting people’s mobility to combat a virus?

One of the most universal measures against the spread of the virus is keeping of physical distance between people (i.e. 1.5 meters or 6 feet apart). This measure is expected to restrict people’s movements for as long as there is no vaccine against the virus. Some countries have implemented even severe measures, such as lockdowns, restrictions on public transport, and on out-bound travels. These measures have had some severe, immediate consequences on people’s lives, but especially for migrants and aspiring migrants these restrictions may have long-lasting consequences. For example, when migrants lose the possibility to visit their family and friends in the place of origin, they may want to move back ‘home’. And aspiring migrants may become more hesitant to move away for those same reasons. This can have lasting effects on global labour markets that heavily depend on the movements of various types of migrants, such as expats and seasonal workers. At the same time, it may become more normative to work from home in certain sectors, which would aid people to stay close to family and friends while doing their work remotely.

A demographer’s view on the pandemic:

I started this piece by saying the pandemic is a health issue. Despite this, I hope to have shown that the pandemic is more than a health issue that only medical scientists can shed light on. Instead, the pandemic has severely affected the lives of individuals; for as long as there is no vaccine against the virus, the fact that we will be combatting the pandemic using social and physical behaviour – such as lockdowns, physical distancing, and mask-wearing –creates good ground for new social studies on people’s mortality awareness, fertility intentions, and migration decisions. I have described some of these avenues in the piece today; now let’s see how the pandemic unfolds!