HAICu wants to act as a reliable guide within the realms of Dutch heritage

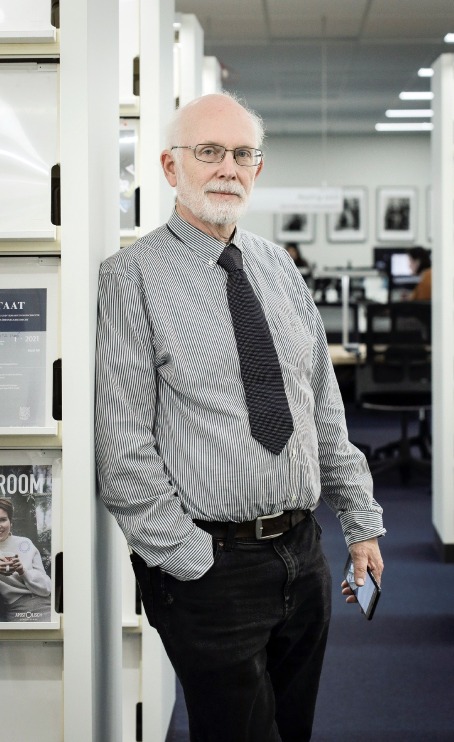

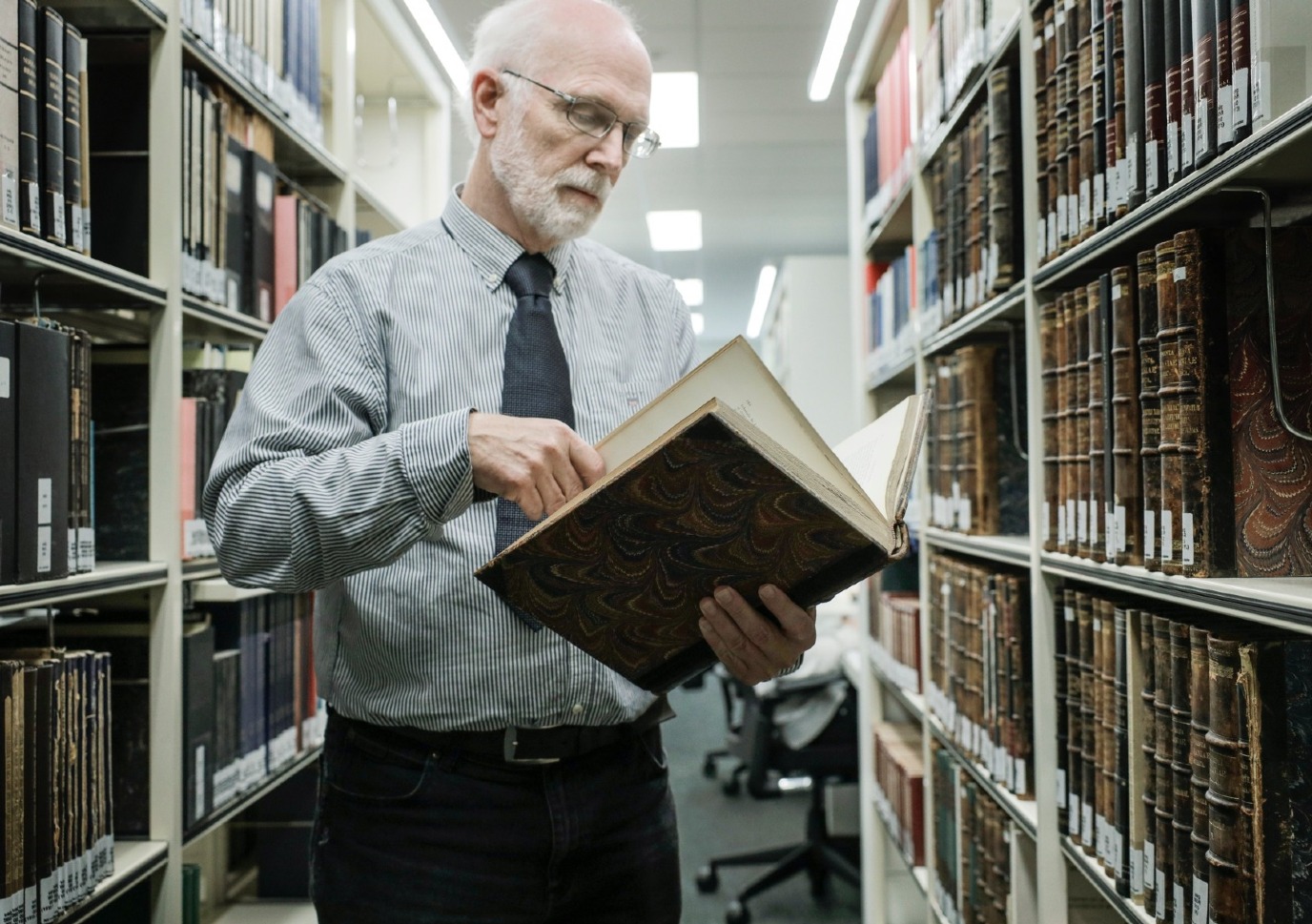

Sound and Vision, the Geheugen van Nederland, Beeldbank Groningen: these days, all sorts of heritage collections are available online. They are crucial sources of information for a wide range of stories. But just imagine being able to browse all these collections to find the context you need for a good story simply by entering a single search term. This is what the HAICu research project hopes to achieve with the aid of artificial intelligence (AI) tools. The project is also meant to make a valuable contribution to the ongoing development of AI. Professor Lambert Schomaker is heading the operation, thanks to €10.3 million of funding that the Dutch National Research Agenda will make available over the next few years.

Text: Thomas Vos / Photos: Henk Veenstra

Scientific hub

‘This is actually quite a difficult tale to tell. These days, most academic stories need to show clear societal impact. Although our project certainly has this impact, it is also helping to build an important theoretical basis for AI and computer science. If you look under the bonnet of language models like ChatGPT, things aren’t quite as slick as they may seem,’ explains Schomaker, Professor of AI at the Faculty of Science and Engineering at the UG.

Different disciplines

Schomaker is talking about the HAICu research project from his office in the Bernoulliborg, the heart of AI at the UG. He is working alongside researchers from various disciplines, including AI, computer science, and digital humanities, to build an important theoretical and practical basis for accessing, linking and contextualizing digital heritage. In their execution of the project, Schomaker and his colleagues on the project are working closely with experts from various heritage institutions. The Dutch National Research Agenda has allocated €10.3 million to the project over the next few years.

Vital

Schomaker describes their approach to the application for funding: ‘First of all, we compiled a problem analysis. It’s hard for the general public to find their way around the mass of multimodal, heterogeneous data published by heritage institutions such as Sound and Vision. But this is vital at a time when many of us have extreme opinions that we consider to be the truth and tend to live in our own little bubbles. Offsetting this, the archives in the heritage institutions reveal a plurality of viewpoints. They show that there is not simply one truth. After all, the perspectives and interests involved in social processes actually vary a great deal.’

What is fake?

Schomaker and his colleagues then asked themselves the following question: how can we use AI to help people to see a range of perspectives, including the source and a broader context? Schomaker: ‘We are currently exposed to an information explosion, so we need to learn how to assess what we see and read in terms of the truth. We all tend to live in our individual bubbles, upholding our own perspectives. It’s really difficult for the average internet user to work out whether something is fake, or to step out of their bubble. Even journalists are wrestling with this problem. We want to find a way for users to browse and assess all kinds of resources using AI, and to arrive at a well-balanced story or narrative

Language-focused

Schomaker sets out a second problem concerning the sharp focus on language of AI models such as ChatGPT. Schomaker: ‘Language is very important, but stripped down, it’s purely an instrument that uses characters to refer to phenomena from the real world. Natural perception and cognition are much more detailed. ChatGPT is not good at spatial thinking. You can’t ask ChatGPT to draw a plan of your house based on a textual description. In order to get anywhere near human perception, AI models must be able to learn from photos, video, audio and 3D models. This is an area that HAICu is explicitly looking into.’

Continuous learning

We must also remember that AI models are expected to learn continuously. ‘It cost $100 million to teach ChatGPT how to learn. But the model is based on a selection of text documents on the internet, dating back a number of years. You really need to keep investing if you want to stay up-to-date, but this is far too expensive and bad for the planet. It’s a problem that still needs to be resolved and an important area of focus of our work. In addition, we must teach AI models how to deal with raw data in tables from businesses, for example, or from historians. This is important because quantitative data often provide useful evidence.’

Few examples

And yet Schomaker wants to start with AI models that are able to carry out a thorough analysis despite being based on a limited number of sources. He refers to previous research in which he was involved into the Dead Sea Scrolls. He and the other researchers used hand-writing recognition and geometry: ‘It was almost a shame that we had to use traditional methods in order to study the very limited number of sources, as we weren’t able to apply modern techniques. HAICu is trying to find ways of using innovations in machine learning to enable AI models to be applied if there are too few examples to learn from. Here in Groningen, we’ve learned a lot from the problems that computers encounter when learning from exotic historical manuscripts.’

Research groups

A lot of groups are involved in implementing HAICu. Interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary research groups are working on themes such as AI and machine learning, and are developing tools. Junior researchers are examining the multimodal (text, sound, vision) sources belonging to heritage institutions to identify problems. Innovation labs are being set up around the heritage institutions so that a broad public and specific target groups (including journalists) can test the tools being developed by the researchers. Schomaker: ‘We don’t just show people how to use the tools, we also make them aware of the potential pitfalls when interpreting data and sources. What’s more, their input and learning examples help with the continuous training of the AI tools.’

Mammoth bones

One of the examples from HAICu mentioned by Schomaker concerns Naturalis Biodiversity Center: ‘They are running a sub-project to develop a tool that enables people to go onto the Maasvlakte searching for bones, from mammoths for example, or from sabre-toothed tigers. They have a sort of Google Lens on their camera phone to then scan such bones and discover all kinds of relevant information.’

Practical

So can anyone scan these bones? Schomaker: ‘We need to be realistic. A lot of small-scale tools will be developed during the process, but not all of them will be of practical use. It will be a process of trial and error. Our primary focus is multimodality. We need to be able to use the tools for different types of sources simultaneously in order to tell a complex story. These multimodal stories are the missing link on television, for example. You see plenty of talking heads, hugely simplifying the underlying reality and the wide-ranging perspectives.’

Info clips

Schomaker thinks that there is room for improvement: ‘You rarely see anyone draw a diagram on a whiteboard. I think it’s a bit arrogant of the traditional media to assume that all those well-educated Dutch people wouldn’t be able to understand a diagram or a table during an explanation. We’re already seeing various online news platforms making excellent info clips for all to see, but it’s a lot of hard work if you want to get it right. I think that the HAICu tools will make it much simpler to construct these info clips.’

Truth

Although these are still early days for HAICu, Schomaker has a clear vision for the future: ‘Thanks to previous projects, the Netherlands has an advantage in the field of AI and cultural heritage. I hope that we can expand on this and that the Netherlands will hold a prominent position in the world of AI. The Netherlands is already responsible for a lot of discoveries. Google and Meta, for example, are watching closely to see how we approach things here. And we’d love to put Groningen well and truly on the map within the Netherlands too. We’re making a lot of progress here, and I think we deserve a higher profile.’

Jantina Tammes School

Operational Director Gerlof Lodewijk says that the HAICu project is mainly serving as an example to Jantina Tammes School of Digital Society, Technology & AI. According to him, the multidisciplinary collaboration within the project is exactly what the UG Schools for Science & Society are aiming for. ‘To us, the major HAICu consortium with 39 members is a prime example of the way we want to work. These complex, multidisciplinary projects are the very reason that the Schools were set up.’

Jantina Tammes and other Schools help to build communities, which can then form the basis for major consortia such as HAICu, Lodewijk continues. He is keen to stress that Jantina Tammes is largely playing a facilitating role at HAICu. ‘We were able help with the resubmission of the project. Also, we’ve already learned a lot from it, and we can apply the knowledge we’ve acquired to new, similar projects. I see HAICu as our future, the path we want to follow on other research projects.’

More information

Lambert Schomaker

More news

-

17 February 2026

The long search for new physics

-

10 February 2026

Why only a small number of planets are suitable for life