Mega-telescoop gaat evolutie van het universum ophelderen

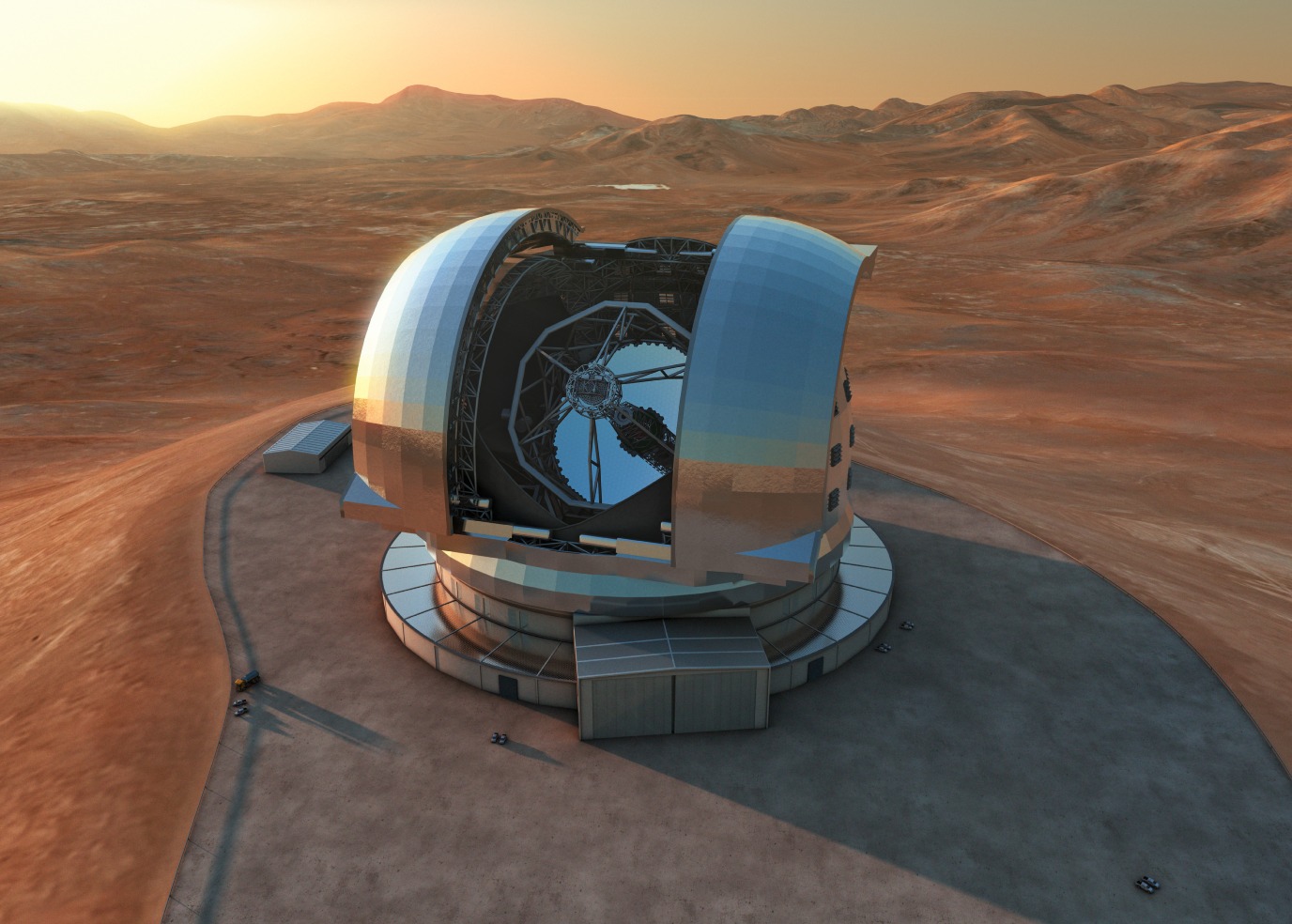

Hij zal zo groot zijn als een voetbalstadion: De European Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), die momenteel in Chili wordt gebouwd. Dankzij een hoofdspiegel met een doorsnede van veertig meter maakt deze telescoop het mogelijk om zeer zwakke objecten waar te nemen die zeer ver weg staan. Sterrenkundigen van de RUG zijn betrokken bij het ontwerp en het gebruik, terwijl verschillende extreem grote onderdelen worden gemaakt in een speciale fabriekshal in Dwingeloo.

FSE Science Newsroom René Fransen

Aan de achterkant van een onopvallende loods op een industrieterrein aan de rand van Dwingeloo kun je een high-tech wereld binnenstappen. Het is de NOVA MAX faciliteit, waar onderzoekfinancier NWO 18 miljoen euro aan bijdraagt, bedoeld voor de komende tien jaar. Doel van NOVA MAX is om de zeer grote onderdelen te bouwen voor instrumenten van de ELT. NOVA is de Nederlandse onderzoekschool voor astronomie, waarin de universiteiten van Amsterdam, Groningen, Leiden en Nijmegen samenwerken. MAX staat voor ‘Manufacturing and Assembly of eXtreme instrumentation’ (Bouw en samenstelling van extreme instrumenten).

(Tekst gaat verder onder de foto)

Vrachtwagens

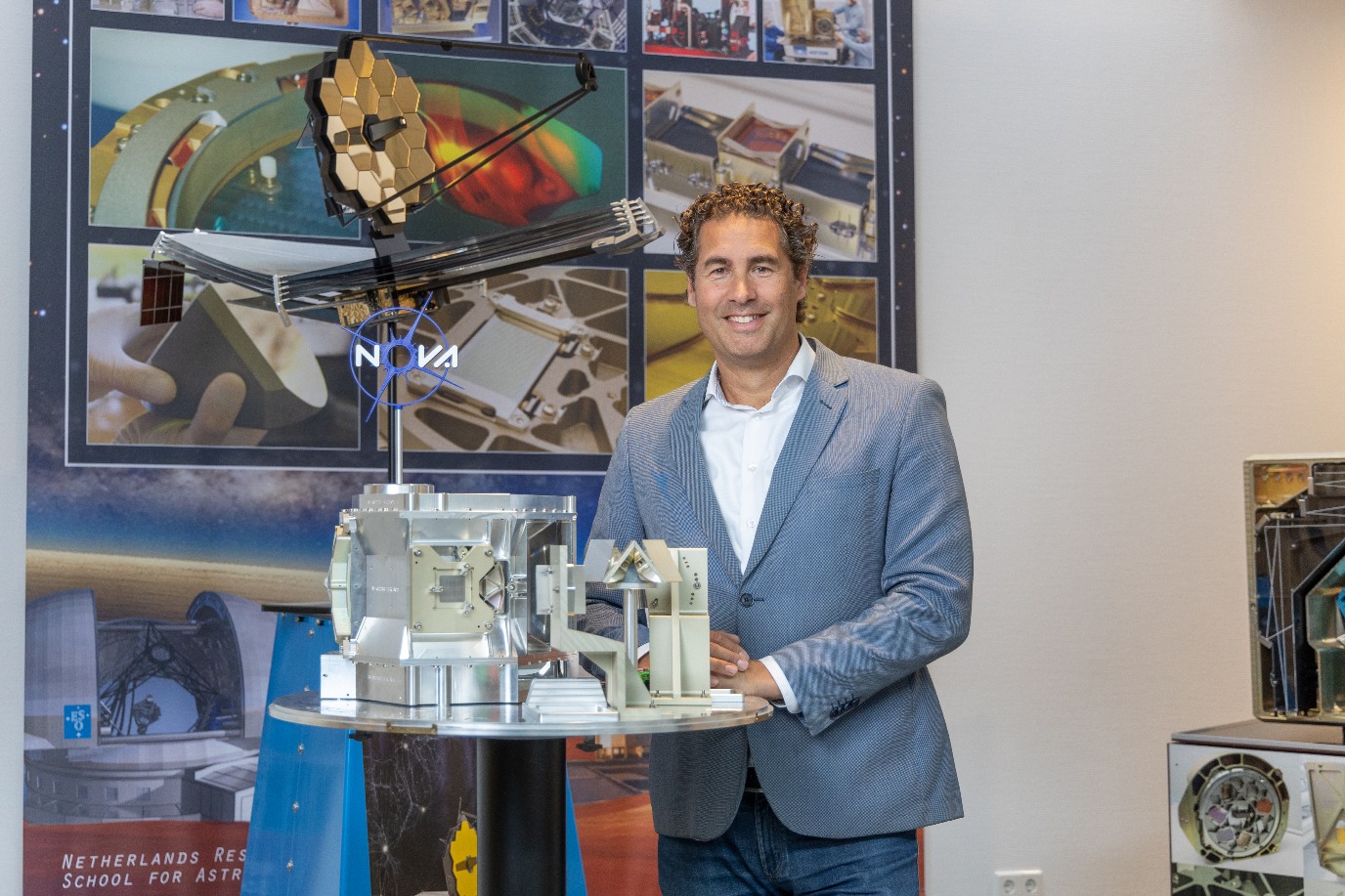

Projectleider van de faciliteit is Ramon Navarro, hoofd van de Optische Infrarood R&D groep van NOVA. Hij legt uit dat de ontwikkeling van ELT onderdelen gebeurt door de Optische Infrarood instrumentatie groep, gevestigd bij ASTRON, het Nederlands instituut voor radioastronomie. Die groep zit even verderop, bij de Dwingeloo radiotelescoop. ‘Maar op die locatie hadden we niet genoeg ruimte voor de freesmachine die we wilden gebruiken, daarom zitten we hier op het industrieterrein.’

Elke verbinding tussen twee stukken levert een kleine afwijking op

De geavanceerde computergestuurde freesmachine is zo groot als een flinke transportbus. Dit soort machines is vooral in gebruik bij autofabrikanten, die er motorblokken voor vrachtwagens mee maken. De freesmachine kan blokken van maximaal 1,3 meter verwerken. Navarro: ‘Het is belangrijk om grote stukken te maken, anders moet je het instrument met veel meer kleinere stukken opbouwen. Elke verbinding tussen twee stukken levert een kleine afwijking op, en dat willen we tot een minimum beperken.’

Precisie

In de zomer van 2023 produceert de machine onderdelen voor MICADO, een camera met 12.000 x 12.000 pixels die de fotonen uit de grote spiegel van ELT opvangt en analyseert. De belangrijkste delen van dit instrument vereisen een precisie op nanometer schaal (een miljoenste millimeter) voor de optische onderdelen en voor de mechanische delen op micrometer schaal (een duizendste millimeter). Operator Menno Schuil is verantwoordelijk voor het programmeren van de freesmachine, en hij moet er voor zorgen dat alles volgens plan verloopt. ‘Ik heb altijd één oog op de machine als hij draait. We produceren momenteel drie grote aluminium wielen, en we hebben maar vijf blokken van het materiaal om ze te maken.’

(Tekst gaat verder onder de foto)

Het is heel eenvoudig om iets fout te doen.

Controleren

Er zit geen ruimte voor fouten in het productieproces, dat jaren zal duren. Los van de beste apparatuur heeft de faciliteit daarom zeer gemotiveerde technici nodig. Navarro: ‘Motivatie is cruciaal, want het is heel eenvoudig om iets fout te doen.’ Voor de training van dit soort toegewijde technici werkt NOVA samen met het technisch onderwijs. ‘Zij zorgen voor de gouden handjes die we nodig hebben.’ Die handen zijn van praktisch geschoolde instrumentmakers tot in computers gespecialiseerde technici.

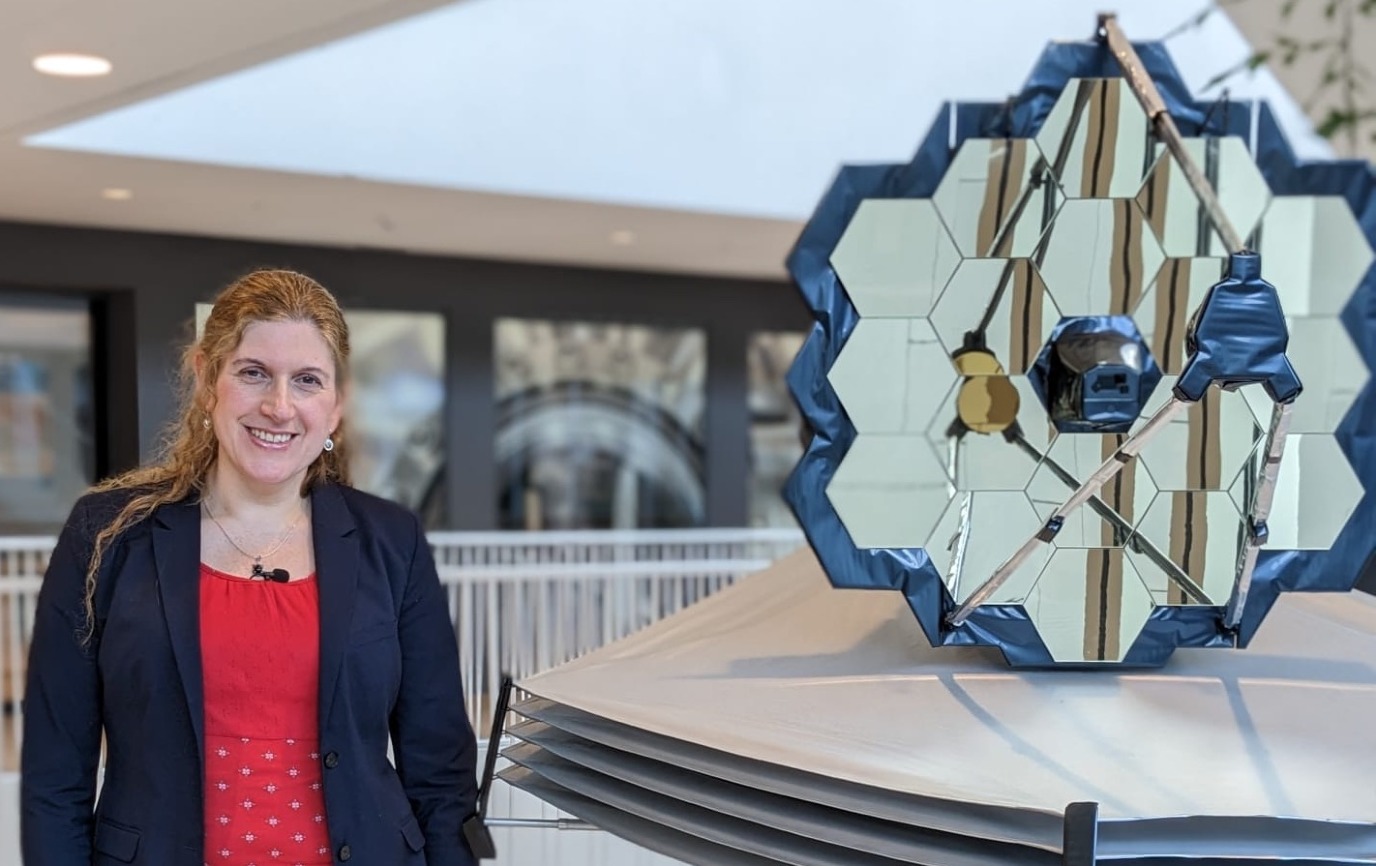

Er zijn ook sterrenkundige betrokken bij de constructie, zoals RUG hoogleraar Eline Tolstoy. Haar taak als Hoofdonderzoeker van het Nederlandse ELT team voor het MICADO instrument is om toezicht te houden op de productie daarvan. ‘Ik ben zelf niet heel technisch, maar ik heb het volste vertrouwen in het technische team. Mijn rol is om te volgen wat er gebeurt en vragen te stellen. Daarnaast moet ik controleren of de belangrijke componenten gemaakt zijn volgens de afgesproken specificaties.’ Soms is een compromis nodig en dan moet het Nederlandse team overleggen met hun Duitse collega’s, en bepalen of het compromis goed genoeg is om de wetenschappelijke doelen te halen.

Belangrijke vragen

Naast dit werk heeft Tolstoy de taak om geld binnen te halen voor het project. ‘We hebben onlangs een subsidie gekregen uit het Open Competitie programma van NWO.’ Ook is ze hoofd van het internationale MICADO Wetenschapsteam. ‘Door het geld dat wij inbrengen zijn we verzekerd van waarneemtijd op de ELT. Als team hebben we besloten de tijd die elk van ons individueel kreeg te bundelen, zodat we 128 nachten hebben, een enorm aantal. We maken nu plannen om in die tijd de meest belangrijke vragen op te pakken die MICADO kan beantwoorden.’

Oersterren

Eén van de doelen is het bestuderen van sterren van verschillende leeftijden, vooral in dwergsterrenstelsels. ‘Je kunt in die stelsels sterren van allerlei leeftijden vinden, en dat zal ons laten zien hoe sterrenstelsels evolueren.’ De Oerknal produceerde vooral waterstof en een beetje helium. Alle zwaardere atomen (door sterrenkundigen ‘metalen’ genoemd) zijn ontstaan door kernfusie in sterren, die zo het metaalgehalte van het universum vergroten. ‘We gaan zoeken aar de oudste sterren, die nog geen metalen bevatten’, legt Tolstoy uit. ‘We weten dat ze er moeten zijn, maar niemand heeft ze tot nu toe ooit waargenomen.’ De grote gevoeligheid van de ELT betekent dat hiermee zeer verre en zeer zwakke objecten zijn waar te nemen, zoals deze oersterren.

Een andere RUG hoogleraar in de sterrenkunde, Karina Caputi, is betrokken bij een instrument voor de ELT dat na MICADO zal worden gebouwd. De MOSAIC spectrograaf zal haar en haar collega’s in staat stellen om grote stukken van de hemel in detail te bestuderen. ‘We onderzoeken zo het Kosmische Web, de grootschalige structuur van het universum.’

(Tekst gaat verder onder de foto)

Filamenten

Sterrenstelsels staan namelijk niet willekeurig verspreid aan de hemel, ze clusteren in filamenten die een web vormen. ‘We willen dat ook bestuderen met de ruimtetelescoop Euclid, die op 1 juli van dit jaar is gelanceerd. Euclid zal een grootschalige kaart van de hemel produceren, maar de spectrograaf van deze telescoop is vrij beperkt. Met MOSAIC kunnen we de chemische samenstelling van de sterrenstelsels in de filamenten in detail bestuderen, aangezien de ELT spiegel van veertig meter veel meer licht verzamelt dan de spiegel van Euclid, van 1,2 meter.’

Op dit moment is het de verwachting dat ELT in 2028 de eerste waarnemingen kan doen. De onderdelen voor MICADO moeten in 2025 verscheept worden naar het Duitse Garching (nabij München), waar de assemblage plaatsvindt. Na uitgebreide testen zou het instrument dan in 2027 in Chili moeten aankomen. ‘Er kunnen natuurlijk vertragingen optreden’, zegt Tolstoy. ‘Het ELT project begon al in 2009, en het is een lange en soms frustrerende reis geweest. Maar het is al die moeite waard, sterrenkundigen van over de hele wereld kijken reikhalzend uit naar de ELT, want ze weten dat deze enorme sprong in grootte fundamentele doorbraken zal opleveren voor allerlei takken van de sterrenkunde.’

Meer nieuws

-

10 maart 2026

Microplastics als een boemerang

-

17 februari 2026

De lange zoektocht naar nieuwe fysica

-

10 februari 2026

Waarom slechts een klein aantal planeten geschikt is voor leven