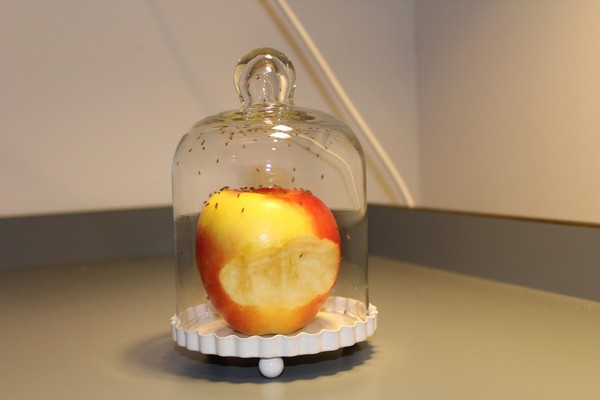

Dit leren fruitvliegjes ons over sociaal zijn

Hoogleraar neurogenetica Jean-Christophe Billeter is ervan overtuigd dat leven in essentie sociaal is. Zelfs dat van fruitvliegjes, die normaal gelden als solitaire soort. In de groep van Billeter aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen ontdekte promovenda Tiphaine Bailly onlangs dat het simpelweg zien van soortgenoten de hormonen van fruitvliegjes al beïnvloedt, en uiteindelijk ook de snelheid en timing waarmee ze eitjes leggen.

FSE Science Newsroom | Charlotte Vlek

Billeter is het wel gewend dat mensen de relevantie niet altijd zien van onderzoek naar fruitvliegjes. ‘Maar,’ legt hij uit, ‘veel fundamentele ontdekkingen uit de genetica van de afgelopen 100 jaar zijn gebaseerd op fruitvliegjes.’ Fruitvliegjes zijn gebruikt bij onderzoek naar uiteenlopende fenomenen in de biologie, waaronder slaap, kanker, de ziekte van Alzheimer, de ziekte van Parkinson. We hebben dingen geleerd over immuniteit met dank aan fruitvliegjes, en we weten dat ons geslacht bepaald wordt door chromosomen met dank aan fruitvliegjes.

En nu tonen fruitvliegjes ons hoe hun lichaam fundamenteel beïnvloed wordt door hun sociale omgeving. Billeter: ‘wij mensen ervaren de wereld ook anders, afhankelijk van het gezelschap waar we in verkeren. Er zijn bijvoorbeeld experimenten geweest die aantonen dat onze ervaring van pijn afneemt als we onder andere mensen zijn.’ Door het effect van de sociale omgeving te bestuderen in fruitvliegjes, hoopt Billeter het mechanisme dat erachter zit beter te begrijpen.

Het effect van de groep op het lichaam

We zijn geneigd te denken dat wat er in ons lichaam gebeurt, alleen van ons als individu afhangt. ‘Maar,’ zegt Billeter, ‘het gaat er ook om met wie we samen zijn. Voor voortplanting zijn alleen een man en een vrouw nodig, maar ook de groep om hen heen heeft een effect op het succes van die voortplanting.’

Als een fruitvliegje alleen is, zal het zijn eitjes ‘s nachts leggen, waarschijnlijk uit veiligheidsoverwegingen vanwege mogelijke vijanden. Maar wanneer ze in een groep zijn, synchroniseren ze de productie van eitjes, en leggen ze ze overdag. Billeter: ‘Ze moeten wel synchroniseren, want als er jongen zijn van verschillende leeftijden, dan zullen ze elkaar aanvallen en zal niemand overleven. Maar als ze gezamenlijk opgroeien, dan kunnen ze gezamenlijk andere bedreigingen bevechten. Dit sociale gedrag dient er dus toe om competitie binnen de groep te voorkomen.’

Deze resultaten zijn het werk van promovenda Tiphaine Bailly, die ook nog bestudeerde hoe dan precies die synchronisatie van de voortplanting plaatsvindt. Het hormoon dat normaal de productie van eitjes reguleert, het juveniel hormoon, wordt beïnvloedt door de sociale context. Wanneer er andere fruitvliegjes in de buurt zijn versnelt de voortplanting, en het maakt dan niet uit wat de leeftijd, het geslacht of de voortplantingsstatus is van die andere fruitvliegjes.

Billeter: ‘Het effect van licht, dat normaal zou zorgen dat de eitjes alleen ‘s nachts gelegd worden, is er dus niet meer wanneer er andere fruitvliegjes in de buurt zijn.’ En om te weten of er anderen in de buurt zijn, hoeven de fruitvliegjes alleen maar te kijken. ‘Dat is wel wat verrassend. In een ander onderzoek hadden we juist gevonden dat ze geur gebruiken om te besluiten of ze zich wel of niet bij een groep fruitvliegjes willen aansluiten.’

Wat fruitvliegjes ons leren over mensen

Deze resultaten doen denken aan het broodjeaapverhaal dat de menstruatiecyclus van vrouwen synchroniseert wanneer ze samen in één huis wonen. Maar Billeter benadrukt: ‘er zijn net zoveel artikelen voor als tegen dit idee, dus we weten niet of dit fenomeen waar is.’ En de kennis over hoe de sociale omgeving de hormonen van fruitvliegjes beïnvloedt, vertelt ons nog niets over hoe dat mogelijk in mensen zou kunnen werken. Hoewel het juveniel hormoon – specifiek voor insecten – wel vergelijkbaar is met menselijke hormonen zoals oestrogeen.

‘Hoe dan ook,’ zegt Billeter, ‘we weten dat een gevoel van eenzaamheid in mensen net zo schadelijk kan zijn als roken of overgewicht, wat al illustreert hoe de sociale omgeving ons raakt. Het kan onze levensduur met jaren bekorten. In fruitvliegjes kunnen we het effect van de sociale omgeving op het lichaam veel gemakkelijker bestuderen. En als we kunnen begrijpen hoe het werkt, helpt ons dat misschien om vergelijkbare werking in andere soorten te begrijpen. Maar dat soort dingen duurt jaren.’

Referentie: Tiphaine P.M. Bailly, Philip Kohlmeier, Rampal S. Etienne, Bregje Wertheim, Jean-Christophe Billeter, Social modulation of oogenesis and egg laying in Drosophila melanogaster, Current Biology, 2023.

Meer nieuws

-

19 december 2025

Mariano Méndez ontvangt Argentijnse RAÍCES-prijs

-

18 december 2025

Waarom innoveren, en voor wie?

-

17 december 2025

Ben Feringa wint Feynmanprijs