Trust in science requires integrity in communication

According to Leah Henderson, it is crucial that we uphold the principle that scientific research is based on evidence. She is a professor by special appointment in Societal Trust, and affiliated with the Rudolf Agricola School of Sustainable Development. Henderson studies how we communicate about science. ‘Nowadays, you often hear people say: ‘’Science is just another opinion.’’ I completely disagree with that.’

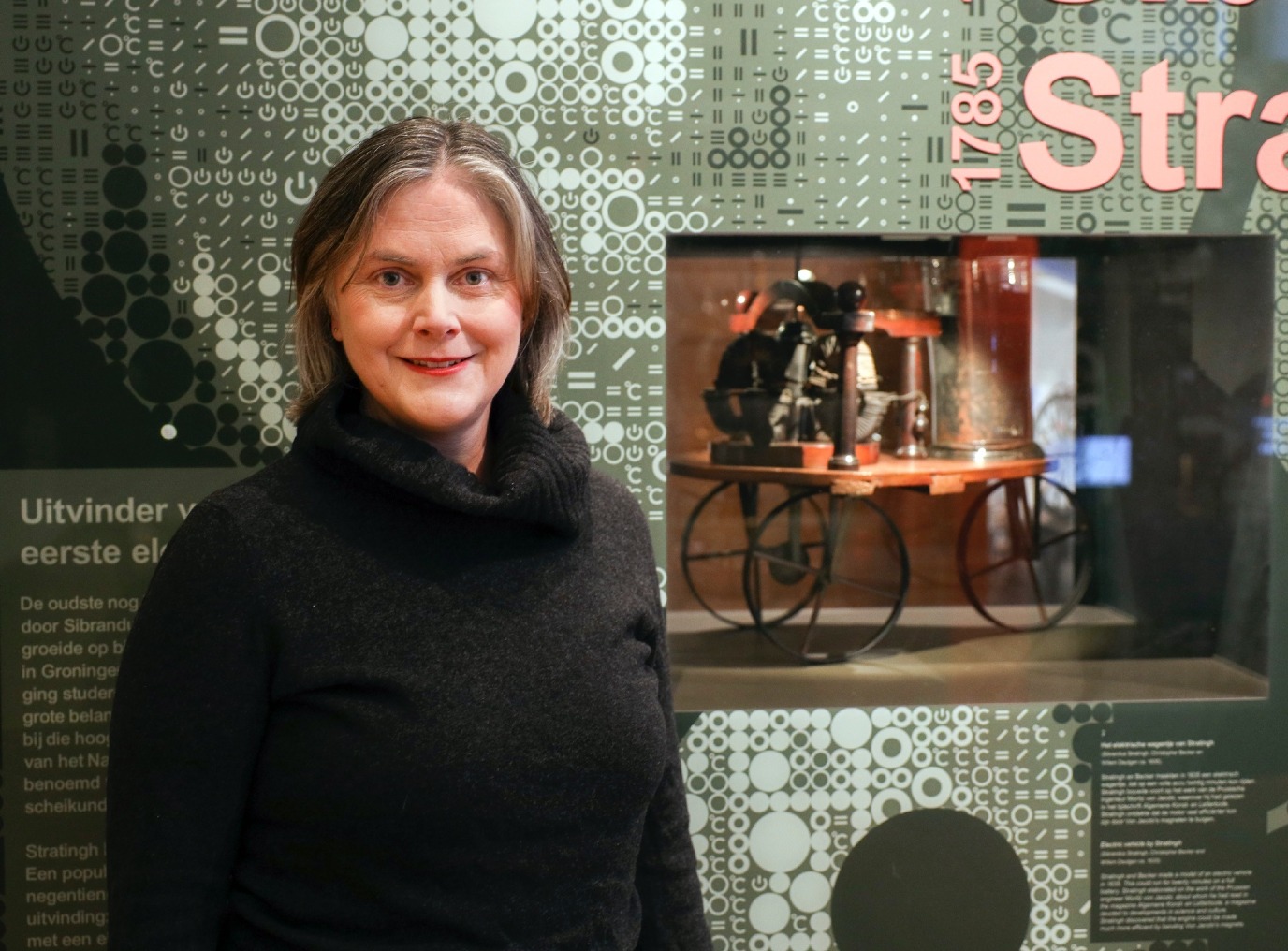

Text: Jelle Posthuma / Photos: Henk Veenstra

Imagine you are in an unfamiliar city, looking for a restaurant. A local guide who knows all the best spots would be a welcome advisor, someone with real expertise. But what if that well-informed local happens to be a close friend of a restaurant owner? That could easily lead to a conflict of interest. What if the guide recommends their friend’s restaurant, even though it is not actually the best option?

Henderson, an expert on societal trust, uses this example to illustrate how trust works. You want someone with local knowledge who also puts your interests first. ‘At its core, trust is about how we can rely on each other. We live in a highly connected society where people play different roles and depend on one another. This works best when people do what they say they will. In that sense, trust is the cement that holds society together.’

Trust, she explains, is based on competence and integrity. ‘We cannot monitor everyone all the time. We have to decide whom to check up on and whom not to. The people we choose not to check are the ones we trust. Trust is an invisible bond between people.’ The same principle applies to institutions and organizations. ‘For example, a minister might ask a committee to prepare a report on a particular topic. That works well as long as the committee is both competent and acts with integrity.’

Evidence-based

Although Henderson’s field is societal trust, she began her academic career as a physicist, specializing in quantum physics. She switched to philosophy for her PhD. ‘Much of the physics I worked on had strong philosophical aspects, and I had always been interested in philosophy.’ Her early research focused on how scientific theories are supported by evidence, particularly during paradigm shifts in science. Are revolutionary changes driven by new evidence, or by social and cultural factors, as thinkers such as Thomas Kuhn suggested? ‘In my work, I defend the former view: paradigm shifts throughout history are based on scientific evidence.’

For Henderson, it is essential to uphold the principle that science is based on evidence. ‘Nowadays you often hear: ‘’Science is just another opinion.’’ I completely disagree. Science is our best attempt to understand the world around us based on evidence. In essence, it is not so different from common sense, but scientific research is systematic and uses reliable methods. Especially in today’s world of alternative facts, it is important to maintain a grip on evidence-based science.’

Communicating science

In recent years, Henderson’s work has focused on how scientific knowledge spreads to policymakers and the wider public. This happens, for example, through science communication and advisory reports. At these interfaces between science and society, different values come into play. And under pressure from these values, the purely science-based message can become unclear. ‘The key question is how we maintain the idea that scientific findings are based on evidence.’

Just as with trust, Henderson says that communication about scientific knowledge must serve the public interest rather than the interests of individuals or groups. ‘Trust always plays a role, including in science. Communication should be grounded in scientific evidence and guided by values that are neither conflicted nor corrupted. The people providing you with this information should not be doing it for any other reason.’

Fossil fuel industry

One of Henderson’s key research areas is climate science. She points to the fossil fuel industry, which also operates at the interfaces of science and society. The industry’s advocates, she explains, try to obscure the science around global warming. ‘They use large-scale disinformation campaigns and possess vast resources and influence. Their goal is to convince people that their product, fossil fuel, causes no harm. In doing so, they try to undermine trust in those who say otherwise: the scientists.’

In extreme cases, this manipulation of trust involves the creation of an echo chamber, where people are encouraged to trust insiders and distrust outsiders. The messages that the fossil industry wants people to hear are amplified within the echo chamber, and scientific voices from outside are dismissed.

Increasing trust

At the same time, trust in science in the Netherlands has slightly increased in recent years, according to research by the Rathenau Institute. Of all major institutions (such as the judiciary and labour unions), trust in science is actually the highest. ‘The fact that people find this surprising says a lot. This is because some people now question science, and their voices have been amplified in public discourse, even though they represent a relatively small group.’

Still, trust in other institutions is declining. And while overall trust in science has slightly increased, the smaller group that distrusts science is also growing. How can we strengthen societal trust? Henderson does not have a straightforward answer. ‘I think we should at least maintain and properly fund reliable information channels, such as public broadcasting, and of course, the suppliers of scientific knowledge as well, namely the universities.’

She also highlights the importance of combating inequality. ‘Wealth inequality is one of the factors that drives information distortion. The group that benefits from the continued exploitation of fossil fuels is quite small, and their interests do not serve the public good. We need to address the extent to which individuals can accumulate wealth. There really needs to be a limit.’

As head of the Societal Trust research group at the Rudolf Agricola School for Sustainable Development, Henderson will continue to study trust in the coming years. ‘My expertise lies in the communication of science, but trust is a much broader topic. In our group, we have many different perspectives on societal trust. Thinking together leads to better thinking. That way, we hope to contribute to the trust infrastructure of our society in the years ahead.’

More information

More news

-

15 September 2025

Successful visit to the UG by Rector of Institut Teknologi Bandung