Moving up in the world through good education

Mineke van Essen is a history educator and an Emeritus Professor who has more than forty years of research into the history of higher education under her belt. She plans to continue sharing her insights into this field with students, junior teachers and the wider public, even after leaving her emeritus position. ‘I also wanted find out for myself if I could get into writing fiction, based on facts that I obtained from source research, of course. A very exciting process, because how far can you go?’

Text: Martin Althof, Communication UG / Photos: © Suzanne Blanchard

This endeavour resulted in the publication of Onderweg naar 1832, een groepsbiografie uit een Groningse school (‘Travelling back to 1832; a group biography from a school in Groningen’). The book describes six young people from working class families, who worked as teachers in the first few decades of the nineteenth century. After the end of French Napoleonic rule over the Netherlands, and before the beginning of industrialization, the city of Groningen saw a lot of changes, especially in the field of education. After the introduction of the first national education law in 1806, there was a strong desire to improve education with well-trained teachers, reasonable salaries and suitable school buildings: subjects that are still on the agenda nearly two centuries later, in 2021...

No starring role for Van Swinderen

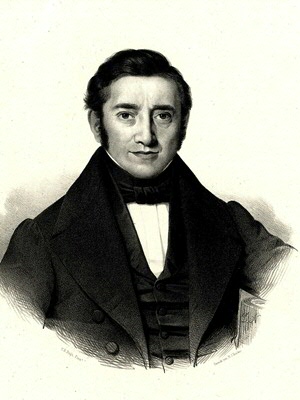

Van Essen explains that she had been familiar with the main characters from the book for some quite some time, from previous studies and publications. One is Theodorus van Swinderen, of course, school inspector since 1807 and the man of the hour at the anniversary celebrations that signal the end of her book. He lived in what is now called the Feithhuis, and was a professor of natural sciences at the University: ‘He was a man of means and belonged among the city’s nobles. As a scientist, he did not stand out, but his true power lay in his skills as an educator. Teaching others was his unique selling point!’ Smiling, she adds: ‘I did not allow him to be the main character in my book. I’m more interested in those other people, with their extraordinary stories. Ordinary people, able to escape their backgrounds and poverty, in a time when this was very difficult. They managed to move up in the world!’

Brugsma: from orphan to director

Van Essen’s issue was that regular people in history do not leave as many traces, forcing her to dig deep and also make some educated guesses about the people in question to bring them to life. Van Essen: ‘The most interesting for me is Beerent Brugsma. Yes, you guessed it: the person that the Brugsmaborg building at Zernike Campus is named after! A great example of how you can become something from nothing. A poor but very gifted orphan who lived in the basement underneath the courthouse at Oude Boteringestraat, Brugsma was discovered at the age of 17 by Van Swinderen, who was director of the teacher training college and who took the boy under his wing. At the time, there were only two such colleges in the entire country. These colleges can be considered the foundation for what are now known as PABO institutions: higher professional education for teachers.’

Two striking ladies

Van Essen emphasizes that the other stories are noteworthy too. Such as the story of Roelf Rijkens, a friend of Brugsma and the son of a village school principal, who wrote child-friendly reading and learning materials, with illustrations by his own hand: ‘At the time, those were considered wonderful children’s books. Another interesting figure is Teunis Hofkamp, a teacher at the only school for the deaf in the entire country of the Netherlands, founded by Henri Daniel Guyot. This school was the first institute for special education in the Netherlands.’ Van Essen has found that women played a subordinate role in education at the time. It took another half-century, until 1871 to be exact, for Aletta Jacobs to become the first female student enrolled at the University of Groningen. Despite this fact, two women play a very prominent part in the book. As Van Essen says: ‘Alberdina Woldendorp, Rijkens’ sister-in-law and an arts and crafts teacher, wrote the first instruction guide for female teachers. Second was Cato Sperwer from Amsterdam, who moved to Groningen to run a boarding school for girls. The final character is a Jewish boy by the name of David Snatich, a brilliant teacher in foreign languages who became the victim of antisemitism.’

By following the lives of the six main characters, Van Essen’s book gives us a sneak peek into the city of Groningen at the time, as well as the state of education. As Van Essen says: ‘It shows that some problems are not bound by place or time. One example is a deadly epidemic that struck the city of Groningen in 1826 and took many lives. A parallel can be drawn to the coronavirus pandemic in the year 2020, the year I wrote the book!’

A focus on teachers

Van Essen has conducted much more research into the history of education in the Netherlands. In 2005, her book on the history of the teacher training college was published: Kwekeling tussen akte en ideaal (‘Newcomer caught between deed and ideal’). In this publication, she posits that throughout this entire history, the wish to improve the programme for teacher training clearly shows. And her new book reveals exactly the same. Van Essen feels strongly that education is mainly about the teachers: ‘They must be trained well and then, once at work, properly paid. In the first half of the nineteenth century, teachers survived on students’ tuition fees. Students brought their fees to school themselves. During his lifetime, Van Swinderen fought for better pay for teachers, from the city as well as the church. He even bragged about his efforts at his own party in 1832!’

Not enough status

Van Essen was sorry to discover that the image and status of the profession has not improved in recent decades. The merging of nursery and primary education in 1984 was not a good development, in her opinion. She describes the idea that people have of teachers: ‘A person with a demanding job who barely gets paid. Unfortunately, this idea is not far removed from reality. The reason? I think this is partly because it’s a profession of servitude, a calling of sorts, that involves a strong idealistic element. Finances then take a back seat. I like to compare it to a cashier in a supermarket, who will refuse to work more hours without extra payment. But a teacher who notices a child left behind in the school playground after hours will never shrug and go home, but will always attempt to solve the problem first. Pupils’ needs are more important than their own.’

Inequality of opportunity

In a certain sense, principal Van Swinderen was far ahead of his time, with his plea for a better teacher training programme and better salaries. Van Essen sighs: ‘We often look for the solution to the problems in education in the Netherlands in structural changes to this education. Committees make plans, with lots of jargon, pilots follow and costs skyrocket. Even an extended three-year bridging period will not solve the issues caused by inequality of opportunity. These issues are not just linked to education, there are many other causes.’ Van Essen emphasizes that more budget is sorely needed to boost the status of the teaching profession. She also believes that we should come to accept that weak schools and vulnerable children require us to put our shoulders to the wheel more: ‘The best schools and privileged children will usually manage just fine without help.’

Contact: Mineke van Essen, h.w.van.essen@rug.nl

More news

-

17 February 2026

From Ghostbuster to Disaster Researcher

-

03 February 2026

‘Such willpower’

-

20 January 2026

Alcohol, texting, and e-bikes