A bike ride into the slavery past

A journey into the Netherlands’ history of slavery will not take you as far from home as you might think. Historian Barbara Henkes is the driving force behind the Traces of the Slavery Past project that resulted in the creation of a walking guide and a cycling guide for Groningen, and Friesland is up next. Guide users will literally be made to stop and think about this part of Dutch history.

Did a slave trader once live on Oude Boteringestraat in the city centre of Groningen? Why, yes indeed! The old, grey house at number 24 used to belong to Thomas van Seeratt (1676-1736). During his last sea voyage in 1715, the captain, who originally hailed from Sweden, purchased 785 slaves from the coastal Loango region in West Africa. He then sold them on the Dutch Caribbean island of Curaçao. The seafarer worked for the prestigious chamber of the Dutch West India Company in Groningen called ‘Kamer Stad en Lande’, which in the 17th and 18th centuries held the Dutch monopoly on the transatlantic slave trade. Seeratt is mainly known as a hero, however, due to his contribution to dike improvements in the northern Netherlands. Due to his efforts, Groningen was spared another terrible flooding disaster after the Christmas Flood of 1717. ‘Groningen still has an excursion boat with his name to honour the seaman,’ says associate professor of contemporary history at the University of Groningen, Barbara Henkes.

Majestic homes and fortifications

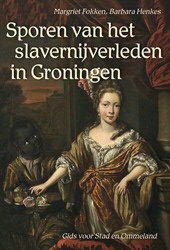

To illuminate the fact that traces of Dutch colonial history can be found in the northern Netherlands as well, Henkes went on a journey of discovery through Groningen and Friesland in search of traces of the country’s slavery past. What began as a journey of discovery in unchartered territories became a large-scale project. In close cooperation with former student Margriet Fokken, Henkes wrote a guide for Groningen with walking and cycling tours past dozens of locations reminiscent of the slavery past: Sporen van het slavernijverleden in Groningen [Traces of the Slavery Past in Groningen] (2016). Publisher Passage will also publish Sporen van het slavernijverleden in Fryslân [Traces of the Slavery Past in Friesland] (2021) next spring.

Plantation owners

The routes pass by majestic homes and fortifications; properties owned by northerners who owned shares in the plantation economy and, as a result, were effectively slave owners, or places where Black servants worked, former slaves from the Dutch colonies. Locations also include the hotels, tobacco factories and coffee roasting houses of yesteryear. After all, in addition to the plantation owners and managers whose pockets were lined with plenty of money, the local middle class also profited from the multinational that was the Dutch West India Company due to the sale of merchandise that came with the returning ships.

Archives of the City of Groningen

The idea for the project came in 2013, when a number of Henkes’ colleagues were involved in the large-scale national celebration of the abolition of slavery, then 150 years ago. Henkes: ‘I live in Amsterdam and I thought to myself, it cannot be that the discussion of the history of slavery is limited to Amsterdam?’ She began searching and wound up at the Groninger Archieven (Groningen Archives), whose employees initially believed that no relevant information would be found there. The same applied to Leeuwarden. Their reactions appear to underscore the importance of Henkes’ mission. Thanks to the information in the National Archives, which can be accessed electronically and contain lists of names of former slave owners who were compensated after slavery was abolished in 1863 – as opposed to freed slaves who were not – researchers were able to trace residents of Groningen and Friesland who were involved in slavery. Henkes: ‘This allowed us to return to the regional archives that were willing to open their doors to our research and have supported us ever since.’ Information from museums in Groningen and Friesland proved invaluable as well. With help from interns, more and more examples of northern involvement were uncovered, linking to southeast Asia, the Caribbean and Brazil.

Abolitionists

Readers of the guides published as part of the project will also become acquainted with northern supporters of the movement to abolish slavery; or ‘abolitionists’, as they were called, among them Groninger farmer and writer Marten Douwes Teenstra, author of the book De negerslaven in de kolonie Suriname en de uitbreiding van het christendom onder de heidense bevolking [The negro slaves in the colony of Suriname and the introduction of Christianity to the heathen population]. Teenstra only just witnessed the abolition of slavery in the Dutch colonies in 1863; he died a year later. He is buried in the cemetery at Snakkeburen in Ulrum, which is of course included in one of the cycling routes. Henkes’ project shows how complex and ambiguous regional connections to the Dutch history of slavery truly are. In 1747, for example, captain of the Dutch West India Company Jurriaan Lindenberg of Groningen – a cousin of Thomas van Seeratt – shipped 628 slaves to Suriname, while he also adopted Arij de Graaff, son of Martinus de Graaff, who drowned. Arij’s mother was most likely a Ghanaian woman named Abenaba who had been purchased and freed by Martinus in 1730. Arij, who was the son of a slave owner and a slave, would himself later become a slave trader, plantation owner and, finally, a Groninger nobleman.

Unequal relationships

Henkes emphasizes that it is important to note that the relationships between European countries and their former colonies have always been unbalanced. This inequality has resulted in consequences for present-day societies. She is very much aware of her own role in this research. ‘I am of course an older white lady, privileged, university educated, someone whose life has at the very least been structurally easier than the lives of descendants of slaves who came to the Netherlands,’ she explains. ‘I am not ashamed of this privilege, but I do believe we should all feel responsible for the inequality in society that is exposed through discussions about racism and our country’s history of slavery.’

Iconoclasm

Speaking of these discussions, what are the historian’s thoughts on the modern-day anti-racist iconoclasm that erupted around the globe as a result of George Floyd’s death at the hands of the police? What should happen to statues of historical figures, such as the colonial ruler Peter Stuyvesant and the aptly named ‘butcher of Banda’, Jan Pieterszoon Coen? ‘I do not believe in the neutral middle ground’, she says. ‘My idea would be to find a creative solution. The most non-creative way would be to add a sign next to one of those statues that reads something like: “he also did things that were not good”.’ Henkes also does not believe that radically removing all the statues is the answer.

No excuse for ignorance

‘Look, a statue of J.P. Coen, that just needs to go. The man was a mass murderer, and that is all there is to it. But Stuyvesant on the other hand, also not exactly a pleasant individual, he should be removed from his base and something else should be put there as a way of commenting on the statue. Wrap the statue itself up in cloth, or smash it to smithereens and then rebuild it again. Do something expressive that serves as a conversation starter. There is so much that you can do. Statues should be replaced by statues, so there is no excuse for ignorance and you cannot simply pass it by any longer.’ This is exactly what Henkes hopes the guides will achieve. ‘Your perspective determines what you see, as well as what you choose to ignore. You have to be willing to see the other side of the story and I am doing my best to provide that information, so that when you walk by one of those stunning houses that Van Seeratt used to own, you will think: at whose expense was he able to live here so lavishly?’

This article has been taken from our alumni magazine Broerstraat 5. Author: Lieke van den Krommenacker.

More news

-

11 March 2026

Japanese distinction for UG ProfessorJanny de Jong

-

04 March 2026

How do you truly make peace after war?

-

14 February 2026

Tumor gone, but where are the words?