Dictators at the first Arts Festival

Saddam Hussein’s wars and ostentatious palaces, Gaddafi’s Bedouin tent, the seemingly moderate Mubarak – Middle East dictatorships have many faces. Nevertheless, according to Dr Kiki Santing, they share a common pattern. She will be expanding on this in greater detail during a short lecture at the first Arts Festival.

Text: Eelco Salverda, Communication UG

A short lecture about Middle East dictators? This seems like an impossible task. And as if it were not difficult enough already, in the title of her presentation, she also asks why there are so many of them... ‘Yes, that’s quite right,’ Dr Santing agrees, with a smile. ‘My answer certainly won’t be a short one. People often see that region’s regimes as just a bunch of brutal thugs in a sandbox. But it’s important to understand what led to this situation. You also need to realize that this phenomenon is not limited to the Middle East. In my lecture, I want to help people to see this side of things.’

Enthusiastic academics

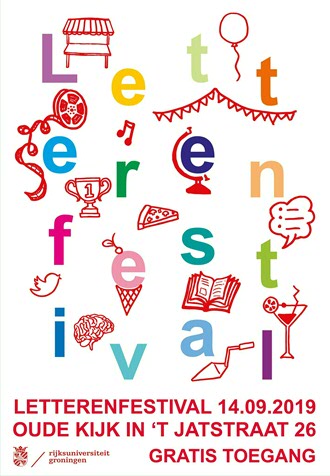

But first, a few details about the first Arts Festival. Santing’s involvement in the festival is not limited to presenting one of the many fascinating mini-lectures – at the start of the interview, she revealed that she was one of the academics who came up with the idea for the festival. She enthusiastically launches into the story behind the afternoon-long event. ‘Together with a couple of young researchers, we came up with the concept of presenting literature and the humanities in a constructive light. News about austerity measures and protests are at the forefront of people’s minds. At the same time, our academic staff are unapologetically enthusiastic about their work. Every last one of them is conducting solid, fascinating and cutting-edge research! The humanities are engaged with – and vital to – society at large. We are very keen to demonstrate this, indeed, I believe it is our duty to do so.’ This is why, on 14 September, there will be a hive of activity in and around the Harmonie building, with a full programme of lectures, workshops, demonstrations, tours, food and music.

Decolonization

Back to the dictators. Santing points out the role that Europe has played in the Middle East, the artificial boundaries that were drawn, decolonization and the major role subsequently played by the militaries of states in the area. There are many parallels between all of these regimes. But is it fair to blame everything on the period after the Second World War? Surely there were authoritarian regimes in that region before the period of European domination? ‘That’s exactly my point,’ says Santing. ‘The region’s traditional structures actually have very little in common with our democracy. It’s reasonable to wonder whether what we see as an ideal form of government is indeed appropriate for the entire world. But colonization was certainly a trigger. We imposed a structure that was alien to the area and that created the conditions in which dictatorial regimes were able to flourish.’

Neither good nor bad

The fall of a dictator is almost invariably followed by civil war, economic crisis and chaos. This triggers nostalgia for the past, for times when, although there was a dictator, there was also peace and security – certainly for those who adapted and who did not step outside the lines. Santing explains: ‘For me, it isn’t so much about whether dictatorship is good or bad. How long did it take us to achieve our ideal form of government? In my view, we need to focus on why these forms of government thrive in some countries. We need to understand that this is a manifestation of underlying political economic and historical structures. It is often counterproductive to overthrow a regime without understanding and addressing their reality.’

Inevitable decline into madness

Santing has built her lecture around the former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein. Was his dictatorship typical of others in the region? ‘He was a kind of model dictator. He went through all the classic phases: army officer, then – as a dictator – first secular then religious, first pro-Western then anti-Western. Remember, all dictators start out as fairly normal leaders, often with good intentions. Some even overthrew a dictator themselves.’ They all seem to follow the same path, one that leads from fairly normal to abnormal – the almost inevitable fate of every dictator. Many young people in the West probably won’t think of Saddam – or the Libyan leader Gaddafi – as a cruel dictator. They are more likely to recall a caricatured figure who behaved oddly and appeared to have lost all touch with reality. That, too, is a characteristic of dictatorships’, says Dr Santing. ‘It’s all or nothing. From the start of your decline and fall, you quickly become a figure of fun. When someone loses their grip on power, all kinds of craziness bubble up to the surface. I’ve been to Iraq. The miserable legacy of numerous wars is still clearly visible. As are the faded trappings of a personality cult. Defaced names, mosaics and portraits. Ostentatious palaces, triumphal arches. It really makes you wonder, “what on earth was that man doing?”’

Opposition

Santing herself does a lot of research into opposition groups in the Middle East. Her eyes shine as she refers to its ‘fascinating field of tension’. ‘A dictator must always balance the pros and cons of permitting any opposition. Sometimes, you have to do that to pacify the people, and sometimes to accommodate lenders such as the IMF. In Egypt, Hosni Mubarak gave the Muslim Brotherhood relatively free rein, allowing them to publish their own newspapers and magazines.’ That very same field of tension is also reflected in the Middle Eastern Studies degree programme itself. The situation in the region is evolving so rapidly that students’ knowledge and frames of reference are changing almost from one cohort to the next. ‘There is no point in trying to fix the content of a current affairs lecture months in advance,’ adds Dr Santing, to illustrate the dynamic nature of her chosen field. ‘One week in advance is the most I can realistically manage.’ ‘A great adventure’ is her way of describing the study of the Middle East. Never a dull moment – neither in the Middle East nor in the research conducted at the Faculty of Arts.

Arts Festival

Santing will present her lecture at the University of Groningen (UG) Arts Festival on 14 September. Throughout the afternoon, the Faculty of Arts will show that its research is varied, dynamic, innovative and relevant to society. Visitors can sit in on mini lectures, participate in workshops, take guided tours, be amazed by short demonstrations and enjoy music, food and drinks. Would you like to find out more about the effects of learning a new language in later life? About humour and the boundaries of freedom of expression? About humanitarian aid, Islam and violence, the special sites associated with ‘learned’ Groningen in the Middle Ages, the movements your tongue makes as you speak or about your ancestors’ eating habits? If so, why not take a look at the Arts Festival website or just pop by on the day at the Harmonie building?

More information

More news

-

04 March 2026

How do you truly make peace after war?

-

14 February 2026

Tumor gone, but where are the words?

-

19 January 2026

Digitization can leave disadvantaged citizens in the lurch