Interview with Christiaan Triebert, Alumnus of the Year

For the first time in his life, Christiaan Triebert has his own place, in Brooklyn. The 28-year-old Visual Investigations Journalist at The New York Times receives requests from all over the world to talk about how to find out facts using open sources available on the Internet. The academic foundation for this was laid at the University of Groningen, which has now chosen him to be its Alumnus of the Year. The award will be presented on 2 September during the opening of the new academic year.

With his bleached blond, swept-back hair, he has the looks of a young Julian Assange. It is mid-June and Christiaan Triebert (28), a former student of the University of Groningen, is taking part by video link in a CNN talk show with Christiane Amanpour. The subject is the research collective Bellingcat, of which he was a prominent member up to the start of this year.

Open sources

A documentary by Dutch filmmakers about Bellingcat, which was established in 2014, has now also been released in the United States. This has given Triebert a new podium for his passion, who in recent years has grown to become an evangelist for open-source investigation. This is fact-finding using open sources such as Google Maps satellite imagery, websites that show shipping and air traffic in real time, online databases, photo and video archives, and social media such as Twitter and Facebook – which are awash with private information.

Bombing

In the show, Triebert talks about a deadly bombing in Baghdad that was covered by international press agencies all over the world. It was Triebert who discovered that the attack had been staged. The people seen on a security camera lying injured on the ground next to a burnt-out car, were in fact healthy men who came rushing to the scene after the car had burst into flames. This kind of open-source investigation is not rocket science, says Triebert in the CNN show. Anyone can do it: ‘All you need is a laptop, an Internet connection, and a fascination with what you are looking at. It’s out there, on the Internet.’

View of Manhattan

The show is over. The video link had been made from the offices of The New York Times, in the heart of Manhattan in New York. Christiaan Triebert left Bellingcat in March this year to join the new, now six-strong Visual Investigations team at the newspaper. Just a week before the show, he finally found an apartment, in Brooklyn. A block away from the beach, with a view over Manhattan’, he tells us a few days after the show with Amanpour. ‘I can even get the boat to work. This is the first place I have ever had to myself! In Groningen, I lived in digs with three other students in the Tuinbouwstraat; then in London I shared with my girlfriend. We also lived together in Malaysia, but I was always travelling around.’

Bellingcat

Bellingcat was launched just before the tragic events of 17 July 2014, when the passenger plane MH17 that was on its way to Kuala Lumpur was shot down above eastern Ukraine. The research collective, set up by the Brit Eliot Higgins, achieved fame in the West with its mapping of the route taken by the Buk rocket, the Russian anti-aircraft missile launcher that the international joint investigation team believes shot down the plane. Bellingcat has carried out many more investigations. One year after its launch, Triebert – who was yet to graduate – was asked to join the team. While writing his graduation thesis on American bombings in Iraq and Syria, Triebert reconstructed the 2016 coup in Turkey for Bellingcat, based on a WhatsApp message written by the organizers of the coup that had made its way onto the Internet. In 2017, he even won a European Press Prize for this. Triebert then travelled around the world to give five-day workshops to journalists on the now celebrated Bellingcat investigation method.

Conflict research

He was an enthusiastic traveller long before this. Before he had got his school diploma, he travelled by train and hitchhiked through Europe. ‘I found it so interesting that, in every country I visited, there was a history’, he says, ‘which is why the Dutch make jokes about the Germans. The Germans, in turn, say all kinds of things about the Austrians. And, if you go from Austria to Hungary, they will tell you to look out. The Hungarians say, “Ooh, Bulgaria is dodgy”, and the Bulgarians say, “Are you going to Turkey? That’s really dangerous.” And when you’re in Turkey, they say, “To Syria? Take care!” And so it goes on, while all the time you meet incredibly friendly people. It seems so obvious, but these are great experiences when you are young. The travels I made when I left school provoked my fascination: if everyone is so nice, why on earth do we have so many problems with each other?’ This fundamental question drove him to take an interest in conflict research. It could also, he says, have something to do with the fact that his father is from Indonesia, which brought him in close contact with the colonial history of the Dutch East Indies and Indonesia’s later independence. ‘This is another reason for my interest in conflicts between people and between countries.’

T his article has been taken from our alumni magazine Broerstraat 5. Text: Jurgen Tiekstra.

Hitchhiking

In the meantime, hitchhiking had become a passion. In 2012, he hitchhiked with two friends from Groningen to Cape Town. On his return, he gave a lecture at the University in which he spoke, without irony, about the love he had experienced along the way. He described hitchhiking as ‘putting your trust in other people’s goodness’. Does he still believe in human goodness? Even after all these years of investigative work, from American bombings that failed to spare children, to a Libyan commander who filmed himself executing prisoners, to the heavy-handed repression of demonstrators by the Sudanese army earlier this year? ‘Yes, it is a paradox’, replies Triebert. ‘On the one hand, the idealism of hitchhiking, and on the other the hard reality of murder. But the idealism is still there. In fact, it’s what keeps me going.’

Love

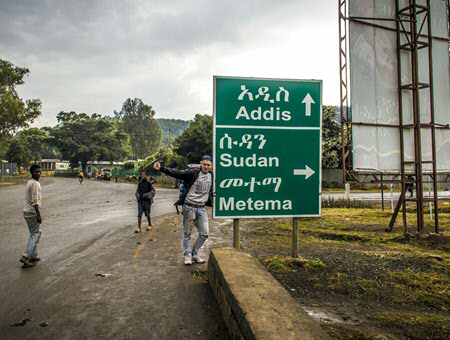

For the first time, he struggles to find the right words. But after a while, his hitchhiker’s optimism returns. ‘I am really glad that I have all that experience of travelling’, he starts. ‘I have been to Afghanistan, I have been to Iraq, and I have been to Syria; in fact, I have visited most of the countries that I now investigate from behind my computer, and in each one I was welcomed with an enormous amount of love, hospitality and warmth. In Sudan, which we are now working on a lot at the New York Times, we were invited into the homes of people we had never met. These people give you food, they give you shelter, and they look after you. It is very important to remember the humane and the individual.’

Russia

‘Take Russia. Everyone is talking about Russia, and now again with the MH17. But what the Kremlin says, or the Russian Ministry of Defence, is not what the Russian people say. In fact, I had the best travel experiences in my life in Russia. I have been to Chechnya, to Moscow, to Murmansk, the far north: fantastic! That really was one of the best trips in my life, along with my journeys to Iran and Sudan. The scenery is beautiful, as is the architecture, but ultimately it is the people who live there. Those journeys shaped my life more than anything else. You can see how enthusiastic it makes me again. That is because it is so important: the world is so connected, but that certainly does not mean that we as people are closer to one another. It’s very strange, and very sad.’

Curriculum vitae

Christaan Triebert (1991) was a student of the University of Groningen from 2010 to 2015. He took a Bachelor’s degree in International Relations & International Organizations and in Philosophy of a Specific Discipline. He also followed modules in Middle Eastern Studies. His graduation thesis was on the use of Facebook by Dutch embassies and consulates. Triebert then went on to obtain a Master’s degree in Conflict, Security and Development from King’s College in London. Sources of inspiration in Groningen include his lecturer Pieter Nanninga, who himself has carried out much research into the use of the media by al-Qaida en IS, and who encouraged Triebert to use Internet sources for his academic research. Just as inspiring was his lecturer Joris Kocken. Triebert: ‘He really believed in what I was doing, which is very important for a student.’

More news

-

04 March 2026

How do you truly make peace after war?

-

14 February 2026

Tumor gone, but where are the words?

-

19 January 2026

Digitization can leave disadvantaged citizens in the lurch