Sick from a broken heart

Heartache! We have all suffered from it at some point in time. The break-up of a relationship has a big impact, and can even lead to depression. But why does that happen to some people and not to others? ‘Understanding heartache can help us better understand depression.’

Text: Merel Weijer / Communication

Love hurts. The depth of the ache may vary, but it’s almost always painful. A break-up puts some people in complete disarray, mentally and physically, unable to function normally for a while. In a few cases, it even becomes pathologic. People get obsessed with the heartache and it doesn’t fade away over time. Others are less affected. They might be sad for a while, but quickly move on, maybe looking for distractions or a new partner.

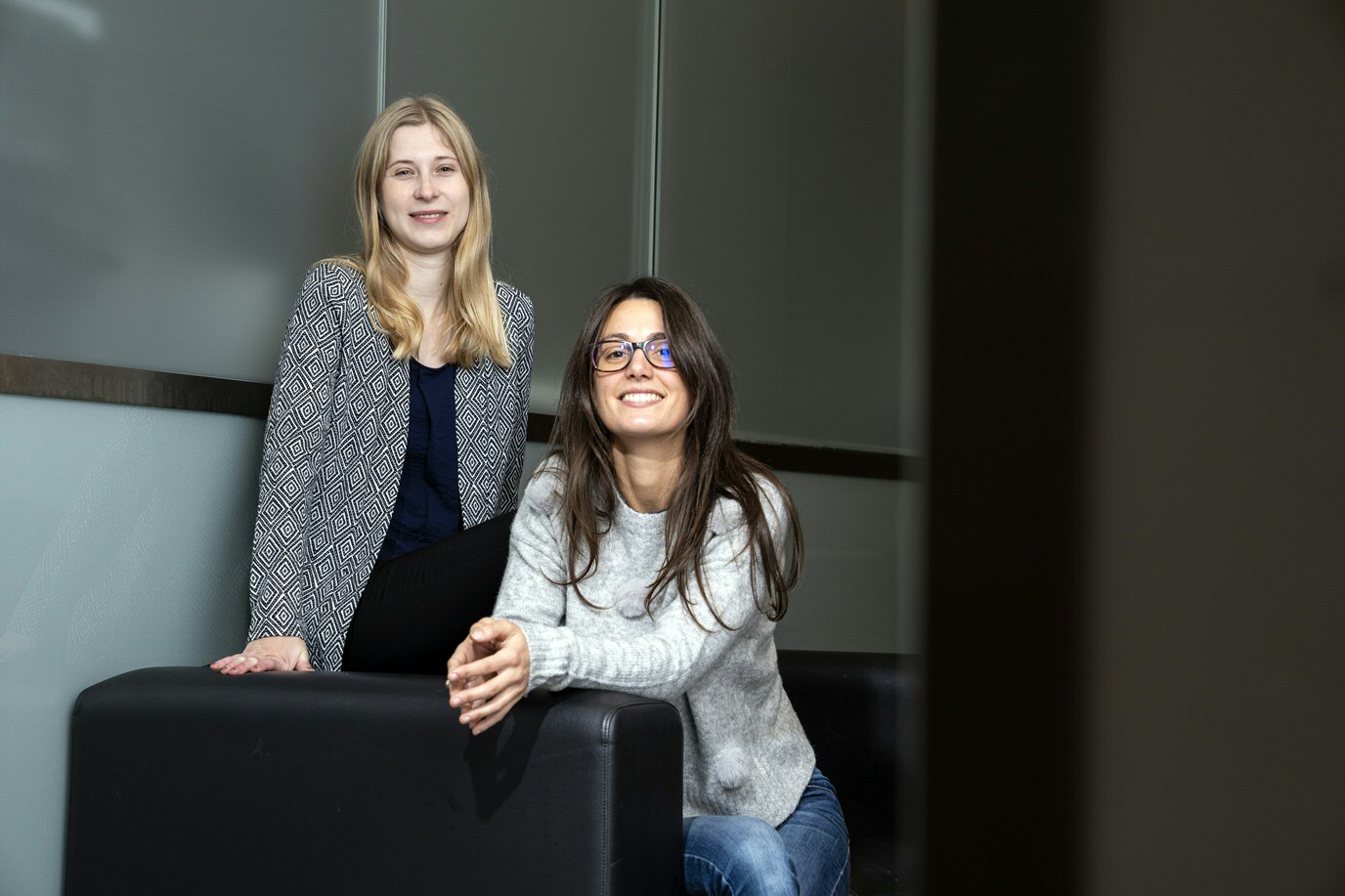

PhD students Sonsoles Alonso Martinez and Anne Verhallen are studying heartache, supervised by Gert ter Horst, Professor of Neurobiology. The goal: to better understand how depression develops.

Measuring feelings of depression

Alonso Martinez and Verhallen are following people who recently went through a break-up for a period of seven months. Among other things, test subjects are asked to fill in questionnaires. At the end, an MRI scan will show how their brain functions compared to others. The questionnaires are meant to measure feelings of depression. Questions concern, for example, the break-up itself, personality and anxiety. The central question of the study is: can we find a marker for people who develop depression?

Heartache as a model

‘In this research project, heartache is used as a model, because we know that depression often develops in people with a genetic predisposition and those suffering from chronic stress’, says Verhallen. ‘But people who are traumatized or in the middle of a divorce are at risk of depression. These are basically healthy people, and we want to learn how these healthy brains can transmute into an unhealthy or depressed brain – this is a key question that has not yet been answered satisfactorily. This group of people is easier to study than, for example, people who are grieving, because the confrontation with what happened is less intense.’

Recovering from a shock

The body and the brain both respond to the stress a break-up can cause. People under stress may have less appetite, lose sleep, have stomach and intestinal pain and get headaches. In addition, all kinds of mental symptoms can develop, like feelings of anxiety and uncertainty, panic attacks and negative thoughts.

‘People cope with stressful situations in different ways’, says Alonso Martinez. ‘That information is crucial to us. Everyone has a certain way of processing what happens to them, and that applies to heartache too. A lot of people feel unwell after a break-up, but not everyone. We are interested in how long these symptoms persist. It is normal to feel bad for three months or so. But there is a point when it is not normal to still be experiencing symptoms. Then it can’t be considered just an ordinary adaptive response anymore.’

Alonso Martinez continues: ‘In this study, we are trying to distinguish four groups of typical responses identified in earlier research. These are representative of the psychological effects a stressful or traumatic event has on most people. You see people who recover quickly, those who take a long time, those who don’t recover and people who don’t suffer at all. The goal is to see how individual differences in the way people cope with stressful events relate to specific patterns of brain activity.’

Wallow in pain or party it up

Earlier research by Ter Horst found that men and women suffering heartache had very different ways of dealing with stress. Women with acute stress wanted to talk about it – a lot. Talking helped them process the pain, and their stress levels had often diminished after a few months. Men responded differently. They started by looking for distractions. They coped with their stress by drinking, going out with friends and looking for a new partner. Because of this, their process of dealing with the pain was only just getting started a few months later.

According to Ter Horst, ‘Eventually they reach the conclusion that they really aren’t having much fun and fall back into their old routines. They might develop depression only five or six months later. In addition, men can live with symptoms of depression much longer and are better at hiding them. When these do rise to the surface they can be a lot more intense than in women, and there is also a much higher risk of suicide. Women are more likely to seek help themselves.’

To avoid the problems presented by these differences, the researchers are focusing on heartache and stress in women only.

A kind of therapy

‘

It can be hard to keep participants motivated during a study’, says Verhallen. ‘Some of our participants might feel fine after a couple of months, and no longer be suffering at all anymore. Then they could ask themselves what purpose their participation serves.’ That is why we keep the questionnaires short and are doing everything by email. It takes just four minutes to fill them in. Every so often participants also receive information and updates about the topic or other interesting studies, to keep them motivated.

‘But we don’t think dropouts will be a major problem, because people might also see it as a kind of therapy. We are not presenting it that way of course, and we won’t be giving out any tips, but participants might still experience it that way’, says Verhallen.

Behind the red line

The research is more an exploratory study, explains Alonso Martinez. It’s not a study that will roll out a list of recommendations. ‘A treatment to keep people with a certain behaviour or type of personality from falling into depression is still far away. The main thing we want to achieve is a measuring stick to use to identify people with a high risk of developing depression.’

According to Alonso Martinez, ‘You want to find some kind of marker and then be able to develop strategies, for example, with medications, behavioural methods for coping and lifestyle changes. With these you could prevent people from crossing the red line into depression. Prevention is crucial, because once someone is in a depression it takes a long time for them to come out of it. Medications are often needed and it has a big impact on the brain and functioning.’

More news

-

15 September 2025

Successful visit to the UG by Rector of Institut Teknologi Bandung