Siberian ‘unicorn’ walked with early humans

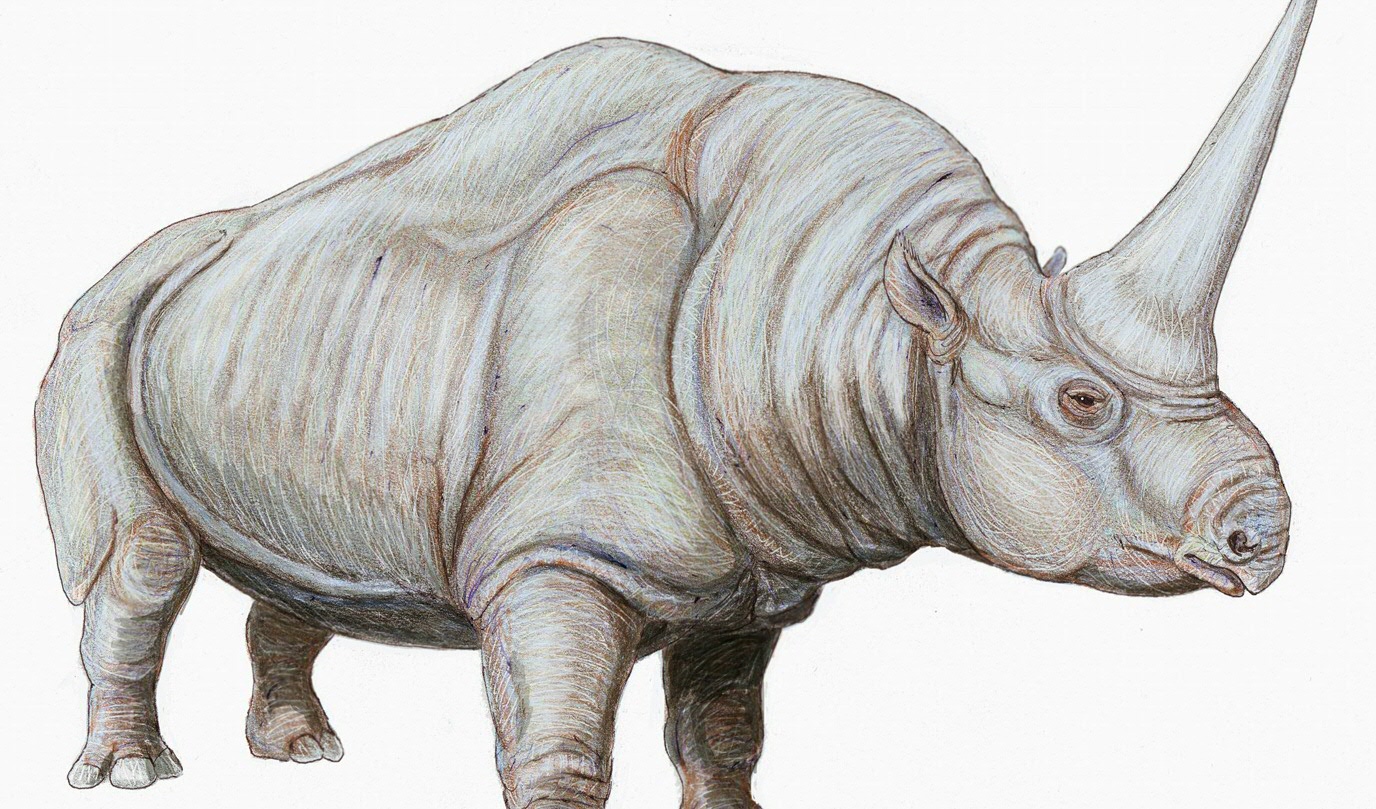

Giant rhinoceroses roamed the Mammoth Steppe of Ice Age Siberia. Like mammoths, they have long since disappeared. They were much larger than modern rhinos, about the size of an elephant, and instead of two horns, they had just one, but it was huge – as big as an adult human. Their scientific name is Elasmotherium, but for obvious reasons they are also widely referred to as ‘Siberian unicorns’.

Over the years, various fossilized Elasmotherium bones have been found in Russia and examined. But since palaeontologists always assumed that the animal became extinct around 200,000 years ago and C-14 dating only works on fossils younger than about 50,000 years, dating was never undertaken.

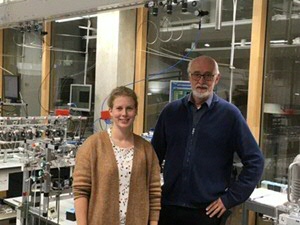

Until, that is, participants in a recent joint Dutch-Russian research project on the mammoth steppe decided to give it a go anyway. Much to their surprise, some of the specimens fell within the time limit for C-14 measurement. One of the members of the project team was Groningen University’s Professor Hans van der Plicht, since retired. He was also Professor by special appointment in Leiden.

A series of 25 Elasmotheria have now been dated. DNA testing has also been carried out on some of them, and other isotopes apart from C-14 have been measured. These unique data were published this week in the prestigious journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

The dating and isotope measurement activities were carried out at the UG Centre for Isotope Research. The youngest ‘unicorn’ dates from around 39,000 years ago, which means that modern man must have been familiar with the species. It also means that this rhino died out much later than previously thought, apparently together with several other large mammals. This wave of extinction was probably the result of major climate fluctuations and the struggle to adapt to a different diet.

The latter is supported by Margot Kuitems’ PhD research on the carbon (13C) and nitrogen (15N) stable isotopes in the carbon-dated bone matter. The Elasmotherium’s striking stable isotope values suggest that the main component of their diet was underground plant parts, such as tubers. This would also explain why they had ever-growing molars. The tubers would have been covered in sand, which would have worn their molars down fast.

The DNA substudy, carried out in Australia, shows that a divergence between the Elasmotherium and other rhino subfamilies started taking place in the Eocene epoch (between 56 and 34 million years ago).

More news

-

15 September 2025

Successful visit to the UG by Rector of Institut Teknologi Bandung