Analyzing the language of sustainability at the University of Groningen. An account of the Responsus event 'Sustainability Reimagined.'

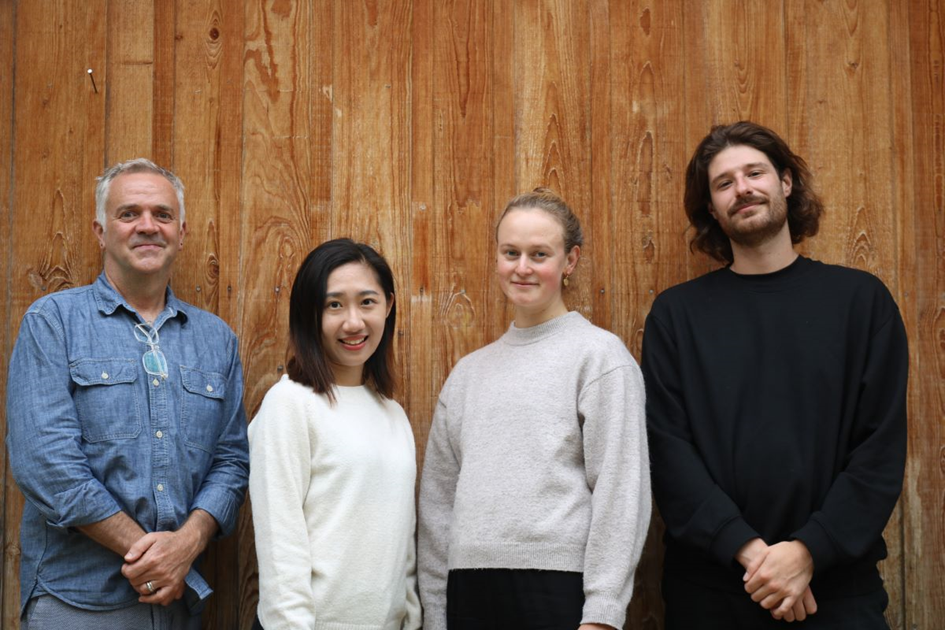

By: Charmaine Kong, Alessandro Pellanda, Laura Wohlgemuth

Charmaine Kong, Alessandro Pellanda, Laura Wohlgemuth took part in the Responsus meeting ‘Sustainability Reimagined: The role of (visual) language in solving humanity's problems .’ They are three doctoral researchers from the University of Bern, Switzerland. Read their account of their trip and the event.

We are three doctoral researchers from the University of Bern (Switzerland) working on a team project titled in short as Articulating Rubbish . Thanks to our supervisor Prof. Crispin Thurlow as well as the vast network of people behind RESPONSUS and ENLIGHT, we were invited to spend two instructive days at the University of Groningen. After a long night traveling across Germany, our train comfortably took us to the lively student city in the Northern Netherlands.

Tjeerd Royaards

Our two-day stay started at the House of Connections, where RESPONSUS organized a public-facing event titled ‘Sustainability Reimagined.’

The programme was structured around lectures and workshops that explore the role of (visual) language in offering sustainable solutions to tackle pressing societal issues. In the opening lecture, comic artist Tjeerd Royaards introduced the important role of humor in communicating climate change and environmental destruction through cartoons. We learned that the visual rhetoric of a burning earth turns out to be rather effective strategy for highlighting the urgency of climate action.

Prof. Arran Stibbe, prof. Crispin Thurlow and dr. Léonie de Jonge

The keynotes presented by Professor Arran Stibbe (on multimodal ecolinguistics) and Professor Crispin Thurlow (on a sociolinguistics of waste) were no less insightful for getting at the role of language in shaping our understanding of sustainability, a term which — despite its omnipresence — can sometimes remain vague and indefinite. We were particularly inspired by Léonie de Jonge’s talk on how Far Right politicians successfully use insects in their campaigning in seemingly harmless but populist ways.

Dissecting business linguistic strategies to blame climate crisis onto individuals

In between lectures, we also had the chance to attend three workshops. To start off, Dr. Erika Darics’ analytic exercise dissected the linguistic strategies that business organizations employ to shift the blame of the current climate crisis onto individuals.

In parallel with this session was dr. Janina Wildfeuer’s workshop, centered on a social semiotic analysis of stock images depicting climate action. Finally, we joined dr. Femke Kramer in ‘rewilding’ language by exploring more novel, creative ways of thinking and writing about nature (as well as our interrelations with it). Ultimately, these hands-on workshops offered the opportunity to (re)discover the transformative potential of (visual) language in more concrete ways.

Exposing ideologies

At the end of the day, we learned that sustainability is not only about reducing individual consumption; more so, it is about decoding the metaphors that threaten democracy, discovering new stories to live by, and critically questioning the disenchantment stories that unvaryingly frame human culture as separate from nature. In this light, then, sustainability is essentially about exposing the ideologies that individualize responsibility, while unveiling structural roots of the problem that are oftentimes obscured.

Networking

However, it is not only the academic input that’s worth mentioning. In the evening, we were invited to join a rather lovely ENLIGHT networking dinner at EETWAAR — a great place for connecting with other scholars and researchers from all over Europe. There’s not much to say besides that we will always remember Groningen for its fascinating foodie scene. This prepared us nicely for the IdeaLab scheduled for the next day.

During this meeting, representatives from the various ENLIGHT universities came together to talk about the role of critical language awareness for more sustainable futures and how this can be applied in practice — what we believe to be a very productive discussion. This was followed by a sustainable tour of Groningen in the afternoon. This tour provided insight into where to buy locally grown food, as well as measures the municipality has implemented to become ‘greener.’

To sum up our brief adventure in the Netherlands, we returned home with a more critical and reflexive understanding of language and communication in (re)shaping how people make sense of the world and perhaps more crucially, how they relate to one another and to the environment. On a final note, we would like to thank the lovely organizers who made all of this possible!

Read all the Responsus blogs:

Responsus Blog 1: The Power of Language in Shaping Sustainability. By: Erika Darics, March 24, 2023

Responsus Blog 2: The Power of Language in Shaping Our Food Choices: From Advertising to Naming Practices. By: Matt Drury, Lecturer at University of Groningen, March 29, 2023

Responsus Blog 3 : 'Soldiers' and 'bad girls': how language shapes health and well-being. By Lotte van Poppel , Assistant Professor at University of Groningen, April 6, 2023

Responsus Blog 4: Humour, Satire, and Framing: The Role of Language in Boosting Planetary and Personal Health'.'By: Massih Zekavat, Researcher and postdoc fellow at The University of Groningen. 17 April 2023

Responsus Blog 5: UN’s communication under scrutiny: How UN-Language obscures moral responsibility for environmental pollution By: Matt Drury. May 15 2023

You can also follow the Responsus Blogs on LinkedIn

Reviving the language of landscape. Languages as storehouses for biocultural and ecological knowledge - against Shifting Baseline Syndrom / Natuuramnesie (Responsus blog 6)

By: Femke Kramer

The previous post in the RESPONSUS (Responsibility, Language and Communication) series about the crucial role language plays in shaping sustainability put the UN’s communication about its own Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) under scrutiny.

This week, we invite you to imagine Life on Land (SDG15) in The Netherlands in the not-too-distant past and reflect on the close interrelation of linguistic diversity with biodiversity. Can the restoration and protection of cultural and natural landscapes benefit from the preservation of equally endangered vocabularies?

In his epic poem Mei (May, 1889—famous for its opening line ‘Een nieuwe lente en een nieuw geluid’ / ‘A new-born springtime and a new-born sound’), the Dutch poet Herman Gorter sent his title heroine on ‘a magical journey’ in the Low Countries. She traversed an enchanting landscape where the scent of carnations filled the air and a vine shrouded a threshing barn. Amidst the buzzing of bees and the singing of larks and nightingales, you could look for elderwood to carve a whistle from. While playing a tune, you could watch calves galloping playfully through a pasture from behind a hawthorn hedgerow. By the end of summer the mulberry coloured blood red next to an old brood wall.

Biodiverse

Needless to say, the setting in which Gorter placed his protagonist was a poetic creation. Yet a biologist friend informs me that The Netherlands during Gorter’s time, while shaped partly by human hands, must actually have been an exceptionally biodiverse paradise, where due to a favourable mix of low human presence and modest pre-industrial land use countless plants and animals felt at home. Soon after, however, progress struck hard, subjecting the Low Countries to a dramatic makeover.

During the past century, the diverse and species-rich landscape in which May experienced her magical journey has been—to quote writer Koos van Zomeren—‘reduced to a spatial construct in which people make and spend money’ which is virtually uninhabitable for life forms that do not fit into an agro-industrial revenue model. The countryside is largely inaccessible and increasingly ‘unreadable’ to us, its human inhabitants. Author Willem van Toorn points to the intangible loss we suffer when our surroundings are stripped of elements that remind us ‘that there is a past, that people lived in that past who had to deal with the world just like us.’ We have been deprived of the opportunity to grow a sense of place.

Shifting Baseline syndrome - natuuramnesie

The collective amnesia that occurs after drastic transformations of the living environment is nowadays referred to as ‘shifting baseline syndrome’ (French: amnésie générationelle; Dutch: natuuramnesie).

The shifted baseline—a ryegrass desert, factory farm or distribution centre occupies the space where once godwits, lapwings, curlews and redshanks raised their chicks—forms a ‘new normal’ that precludes imagining the world our ancestors shared with a plethora of other creatures.

Another consequence of this amnesia: if you’ve never heard a lark or seen a mulberry bloom, you probably will not care so much that the last lark nests are being chopped up in mowers or a mulberry tree disappears in a wood chipper. At the same time, the vocabulary that our ancestors used when speaking about their surroundings is falling into disuse, giving way to a simplified generic language in which larks, godwits and redshanks are simply 'birds' and a hawthorn hedge is a random 'shrubbery'.

Extinct words

There is a growing awareness of the 'close interrelation of linguistic and cultural diversities with biodiversity', as stated in a recent article surveying successful cases of 'language reclamation' by indigenous communities whose languages—storehouses for biocultural and ecological knowledge—were threatened with extinction along with the destruction of their living environment. Let's not overlook the fact that in Western societies, too, impoverishment of nature and landscapes is accompanied by lexical obsolescence and word loss—and conversely, that nature and landscape protection and restoration should go hand in hand with reviving and educating the language in which we can communicate about them.

With this premise, British nature writer Robert Macfarlane has catalogued ancient and nearly extinct words that refer to landscape and natural elements with extreme precision and nuance. If we relearn, use and pass on such words, we can learn and teach to perceive, understand, appreciate and protect the things and beings they refer to. As long as traces of them can still be found...

We hope you are enjoying the mini-series about language and sustainability of the RESPONSUS group.

UN’s communication under scrutiny:

How UN-Language obscures moral responsibility for environmental pollution

By: Matt Drury

This week I put the UN’s communication under scrutiny - after all we could expect it to be the most authoritative voice that sets the tone for work related to SDGs. The UN doesn’t have an easy job though: communication about climate change is extremely challenging.

My examination is inspired by critical approaches which consider language use as a social practice, focusing on power relations and ideologies and how they are constructed and maintained through discourse. Here, I critically explore communication from the UN about SDG14: Life Under Water.

Ideology of consumption

In the infographic on the SDG website, readers are encouraged to ‘conserve and sustainably use the oceans, sea and marine resources for sustainable development’. This description itself is based on an ideology of consumption. Words such as ‘use’, ‘resources’, and ‘development’ suggest that the oceans and their contents exist for human benefit.

Many other ecological and environmental issues are presented in the infographic too, like ‘overfishing’, ‘plastic pollution’, ‘acidification’, and ‘ocean warming’.

Erasure of moral responsibility

A more detailed look at these issues shows that these are all nominalisations of processes; that is, the verb has been changed to a noun. Doing this has the function of removing the doer of an action from a sentence, and as we can see, nowhere in the document is such a doer mentioned. As such, no moral responsibility for these issues is directly attributed. While we can assume that these are all caused by people, there’s no information about which people or how they were caused. Indeed, the only people that are represented in the infographic are ‘90% of the world’s fishers’. They are represented as a statistic, what van Leeuwen (2008) would call aggregation.

There is some use of emotive language in the infographic: ‘plastic pollution is choking the ocean’ and ‘Ocean acidification is threatening marine life’. While these metaphors of violence may help to garner attention, again the social actors responsible for the causes are not mentioned.

This “erasure” of the responsible parties serves to focus our attention on the issues rather than the solutions. In general, presenting such complex (wicked) problems as battles or war doesn’t adequately equip us to deal with them. We fight wars and can win by defeating an enemy. However, climate change, acidification, and plastic pollution are not the enemy; it is us, humans, who are responsible. We can’t fight ourselves and win!! The other issue with a war metaphor is how do we know when we've won? As such, new metaphors need to be found.

Important tool in promoting social action

As we can see from this short critical analysis, the choice of both words and grammar can convey messages about the ideologies which underlie a text. The erasure of the morally responsible actors reproduce an anthropocentric discourse which underlies much of our thinking and communication about sustainability. In addition, metaphors provide an incredibly important tool in promoting social action, but we need to choose the right one for our needs.

Humour, Satire, and Framing: The Role of Language in Boosting Planetary and Personal Health

By: Massih Zekavat, Researcher and postdoc fellow at The University of Groningen (RUG)

Three weeks ago, RESPONSUS (Responsibility, Language and Communication) started a series of blogs to show how crucial language and communication are in shaping sustainability. Last week we read an intriguing article about the role of metaphors written by Lotte van Poppel. This week we explore the role of language and discourse in shaping and communicating sustainability where we’ll see how language negotiates individual, social, and ecospheric well-being (#sdg3 ).

It is difficult to ignore how far planetary health (#sdg13, #sdg14, #sdg15) could impact individual health and well-being. We all know how necessary clean air or potable water are for living a healthy life. Nevertheless, it is not easy to persuade everyone to put planetary health before their immediate needs and desires. Why should I exchange the ease and luxury of driving to my destination with a sweaty outfit and a cartoonishly red nose that riding my bicycle affords? Abstaining from the immediate satisfaction of eating a juicy steak hardly compares to saving the planet for the future generations after all.

Framing environmental messages in terms of health and well-being can be particularly effective in encouraging people to reconsider their environmental behaviours. Framing is defined as “setting of an issue within an appropriate context to achieve a desired interpretation or perspective” (Shome & Marx, 2009, p. 11; https://doi.org/10.7916/d8-byzb-0s23). Framing is not the only venue where language, images, and motion pictures can be effectively employed to promote good health and well-being. The emerging discipline of medical humanities is yet another promising path.

So instead of asking people to use public transport and cut down on their meat consumption, one can remind them of the immediate negative impacts of exhaust emissions and trans fats on their health and wellbeing and that of their loved ones. Using ‘gain’ or ‘loss’ frames means phrasing the same choice or option either in negative or positive terms. The message remains the same; rather, it is communicated in terms of its negative or positive consequences. Instead of foregrounding the negative consequences of unbridled meat consumption like CO2 emissions, water consumption and pollution, or animal suffering, we can focus on the benefits gained from reducing meat consumption like preventing cardiovascular diseases.

As we contend in our book, humour is also a potent strategy for framing environmental messages: it fosters positive emotions and good mood when communicating the message and makes it more memorable (like the subtle humour in Mike Sedden’s cartoon of our header). For more inspiration have a look at Instagram page of Gesunde Erde - Gesunde Menschen Foundation (healthy planet, healthy people) and of course my co-authored book (with Tabea Scheel): “Satire, Humor, and Environmental Crises”.

See you back next week when we will use the language lens to explore #sdg14 - Life under water.

Notes

Boykoff, M. (2019). Creative (climate) communications: Productive pathways for science, policy and society. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108164047

Shome, D., & Marx, S. (2009). The psychology of climate change communication: A guide for scientists, journalists, educators, political aides, and the interested public. Center for Research on Environmental Decisions, Columbia University.

Zekavat, M., & Scheel, T. (2023). Satire, humor, and environmental crises. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003055143

#sdg #humor #comedy #communication #psychology #humanities Dr. med. Eckart von Hirschhausen Tabea Scheel Max Boykoff

Responsus Blog 3: 'Soldiers' and 'bad girls': how language shapes health and well-being

By Lotte van Poppel , Assistant Professor at University of Groningen, April 6, 2023

SDG#3: Good Health and Well-being: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

Two weeks ago, RESPONSUS (Responsibility, Language and Communication) started a series of blogs to show how language and communication are crucial in shaping sustainability. Last week, Matt Drury revealed the language politics surrounding food. This week, let’s shine some light on why language matters when we talk about health and well-being (SDG#3).

Have you wondered, for example, how language shaped your ideas and perceptions about the threat of Covid-19? Why does it matter if we talk about a pandemic as a 'journey', a 'natural disaster', or as a 'fight'? Because each of these metaphors activates different ideas, and justifies different actions.

No wonder many world leaders were often criticised for using metaphorical war language and visuals. In a war, it is justified to install a curfew and give full support to the soldiers fighting for the nation’s freedom. But a virus is not a foreign army. Is this metaphor effective? Or damaging? Some research shows that using the language of "fighting", "soldiers" and "frontline" persuades certain groups of people to support very strict Covid-19 measures, especially those people who rely on alternative news sources. But other metaphors may be more useful to mobilise society - like "fighting fire" (as this research found). Language - and here specifically metaphors - shapes our reasoning and decision-making.

And while language use in the political arena may have gotten most of the limelight, language affects our health and well-being in more subtle ways. For instance, violent language can be so powerful that patients suffering from cancer prefer more aggressive forms of cancer treatment over preventive types of behaviour. War metaphors may work differently for different patients, offering both empowering and disempowering frames: they allow patients to see themselves as a powerful fighter who defeats cancer or, contrastingly, as a passive victim losing the fight from their enemy.

But there are countless ways in which the power of language can manifest in the context of health and well-being. Think about how we use our words to talk social expectations, approvals and disapprovals into being. We use language to stigmatise groups and behaviours. In many cultures, (young) women are being depicted by their community as "bad girls'' for being sexually active, potentially affecting their (mental) health and health behaviours. Or, using a different kind of framing, patients suffering from HIV/AIDS, which no longer needs to be a lethal disease, could be "living with" AIDS instead of "dying from" AIDS. By no longer seeing their diagnosis as a "death sentence", patients can cope with it better.

Meaning-making in language and culture is important, whether we talk about grand political speeches, subtle societal references or the intimacy of the doctor's office. If we become aware of these mechanisms, we can open the way to more fruitful and inclusive language use - and with it a great chance for a healthier society!

Responsus Blog 2: The Power of Language in Shaping Our Food Choices: From Advertising to Naming Practices

By: Matt Drury , Lecturer at University of Groningen, March 29, 2023

Last week we in RESPONSUS (Responsibility, Language and Communication) embarked on a series about the crucial role language plays in shaping sustainability. This week I explore the significant role language plays in shaping SGD#2 - the main aim of which is to achieve food security. This is a pressing issue: the Earth’s population is growing but resources are diminishing. The politics of food production and food distribution are more prominent than ever.

And language plays a key role in this process. Research has shown that we perceive taste differently depending on how a food is labelled: evidently 75% lean burger tastes better than a 25% fat burger! Fancier menu descriptions do not only sound higher quality - we are ready to pay more for the food too!

Conscious linguistic choices (or food rhetoric) - like describing something as "juicy" or "tender" can make a food seem more appealing, while labelling something as "healthy" or "organic" can make it more attractive to health-conscious individuals.

The language effect is very powerful - as many players in the food production and distribution chain will attest. No wonder that the dairy and meat industries have so vehemently opposed the use of animal product terms for plant-based alternatives in ads. According to EU legislation, oat “drink” is now preferred to any mention of “milk” (although this is not the case in the US). So far, in most EU countries, plant-based alternatives are still allowed to be called sausages and steaks, but there are signs that this could be changing. This heated debate over the words used to describe products illustrates the importance of word choice. Clearly, the language chosen has the potential to have a great impact on purchasing attitudes, which is why vested interests have fought so hard to remove these labels.

Naming practices can also affect our relationship to the natural environment. For example, we generally avoid naming animals directly when we talk about eating them. Instead, we use words such as “meat”, “beef”, “pork”, and “steak”. In high-profile international and national reports, animals are discursively represented as objects for us to use due to the fact that they are unquestionably part of our food system. This is done by their construction as ‘either aggregated—as livestock, units of production and resources, or materialised—as meat and protein.’ (p69). From food labelling and packaging and social media influencers to public policy, texts and visual language play a fundamental role shaping our perception of taste, health benefits, and cultural significance. By analysing these texts critically, we can uncover the power dimensions and interests behind certain decisions around naming practices, highlighting the importance of language in shaping our attitudes and behaviours towards food.

Responsus Blog 1: The Power of Language in Shaping Sustainability

By: Erika Darics, March 24, 2023

When you hear the word "sustainability," what comes to mind? Perhaps images of green forests and rolling hills, or maybe you think of cutting-edge technologies that harness renewable energy sources. Research repeatedly shows that sustainability is primarily associated with the environment and ecology: consider the word cloud below (source). But it is about so much more than that.

The United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals reflect this broader understanding. Sustainability is about ensuring the wellbeing of our planet as well as its people, promoting gender equality, a decent work environment and productive employment, fostering responsible consumption, and building sustainable, democratic communities. And it all starts with education – educating ourselves and others about the issues that matter, and inspiring action towards positive change.

In this process, communication is crucial. The way we communicate has the power to shape our understanding of the world, to influence our attitudes and behaviors, and to inspire action towards a sustainable future. Words and images 'talk' our realities into being. The language we use creates frames of interpretation about urgency, seriousness, and consequently affect our willingness to act. It is not surprising that the climate crisis has been dubbed as a major communications failure.

That's why linguists and discourse analysts need to be part of the conversation about sustainability efforts. By working together with other disciplines, we can show how language and images frame societal issues. Our work can shed light on how specific communication strategies influence attitudes and behaviors towards sustainability issues and promote more effective communication strategies that lead to positive change: whether it has to do with life below water, on land, at work, or sustainable communities.

We invite you to our upcoming series about why language and and visual communication matter. Follow along as we share scholarly work, surprising examples, and specific cases that highlight the importance of #language #multimodality and #discourse for all #sustainable development goals.

Join the RESPONSUS (Responsibility, Language and Communication) group on LinkedIn and follow the Agricola School for Sustainable Development for further info.

Responsus Blog 2: The Power of Language in Shaping Our Food Choices: From Advertising to Naming Practices.By: Matt Drury, Lecturer at University of Groningen, March 29, 2023

More news

-

15 September 2025

Successful visit to the UG by Rector of Institut Teknologi Bandung