Is speciation adaptive?

Speciation – the origin of new species – is the source of the diversity of life. A theory of speciation is essential to link poorly understood macro-evolutionary processes, such as the origin of biodiversity and adaptive radiation, to well understood micro-evolutionary processes, such as allele frequency change due to natural or sexual selection. An important question is whether, and to what extent, the process of speciation is 'adaptive', i.e., driven by natural and/or sexual selection. In his seminal book on the Origin of Species by Natural Selection, Darwin (1859) envisaged speciation as the result of two processes: selection for diversification allowing the exploitation of previously unused opportunities, and the extinction of intermediate forms as a consequence of severe competition among these forms. Hence, according to Darwin selection plays a major role in the speciation process. However, Darwin's verbal arguments are often vague and not always convincing, partly because of his pre-Mendelian ideas on inheritance. It is partly for this reason that the founding fathers of the "Modern Synthesis" largely discarded Darwin's view on speciation, giving non-selective factors like geographic isolation and the accumulation of potentially deleterious mutations by genetic drift a much more prominent role than selection.

In the last decade, the view that adaptive speciation is a rare and unlikely phenomenon has been challenged by two recent developments in speciation theory, which seem to suggest that natural and sexual selection can be more powerful in the creation of new species than the traditional models seem to suggest. First, a new class of 'ecological' models of speciation selection models convincingly demonstrates how frequency dependent selection can lead to the evolution of ecological differentiation. Second, ‘sexual selection’ models of speciation show how divergent sexual selection can lead to the diversification of mating strategies and, hence. However, taken on their own, both modelling approaches are not fully convincing. Ecological models can explain the stable coexistence of incipient daughter species in the face of interspecific competition, but they are typically vague about the evolution of reproductive isolation. Sexual selection models can explain the evolution of prezygotic reproductive isolation, but they are typically vague on questions like ecological coexistence. By means of integrated models, incorporating both ecological interactions and sexual selection, we demonstrated that disruptive selection on both ecological and mating strategies is necessary, but not sufficient, for speciation to occur. To achieve speciation, mating must at least partly reflect ecological characteristics.

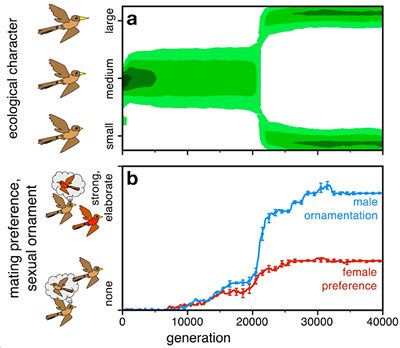

In an invited review paper (Weissing, Edelaar & Van Doorn, BES, 2011), we argue that the current tendency to view natural and sexual selection as alternative and contrasting mechanisms underlying speciation is counterproductive and misleading. In fact, adaptive speciation can most easily be achieved when natural and sexual selection work in concert. This is exemplified in a recent model (Van Doorn, Edelaar & Weissing, Science, 2009) that shows how natural and sexual selection can mutually reinforce each other, thereby achieving adaptive speciation under conditions where speciation would have been considered highly unlikely by classical theory (Figure 1).