Sky Islands: A Biodiversity Hotspot Under Threat

It was February 28, 2025, a warm and above all dry Spring afternoon in Tucson, AZ.(1) I was sitting in the cool terrarium of Tucson International Airport, streaming a movie on my phone I knew I wasn’t going to finish. I was waiting to be picked up. For four days I had stayed in Tucson, cruising around town, going on multiple hikes and visiting old friends whom I hadn’t seen in years. Tucson had been my home from 2013 to 2016, during which I got to know the surrounding country, particularly the Santa Catalina Mountains, which form the northern border of Tucson. Viewed from my family’s old home on North Campbell Avenue, the Catalinas appear regal, a bright granite crown dusted by a fine layer of vegetation, a lot of it very spiny. To me, the experience of looking up at those mountains is mesmerizing. In a place where one might only expect dust and a couple of the iconic fork-shaped saguaro cacti, islands rise up from the desert floor to immense heights, constituting a playground to a broad array of Life.

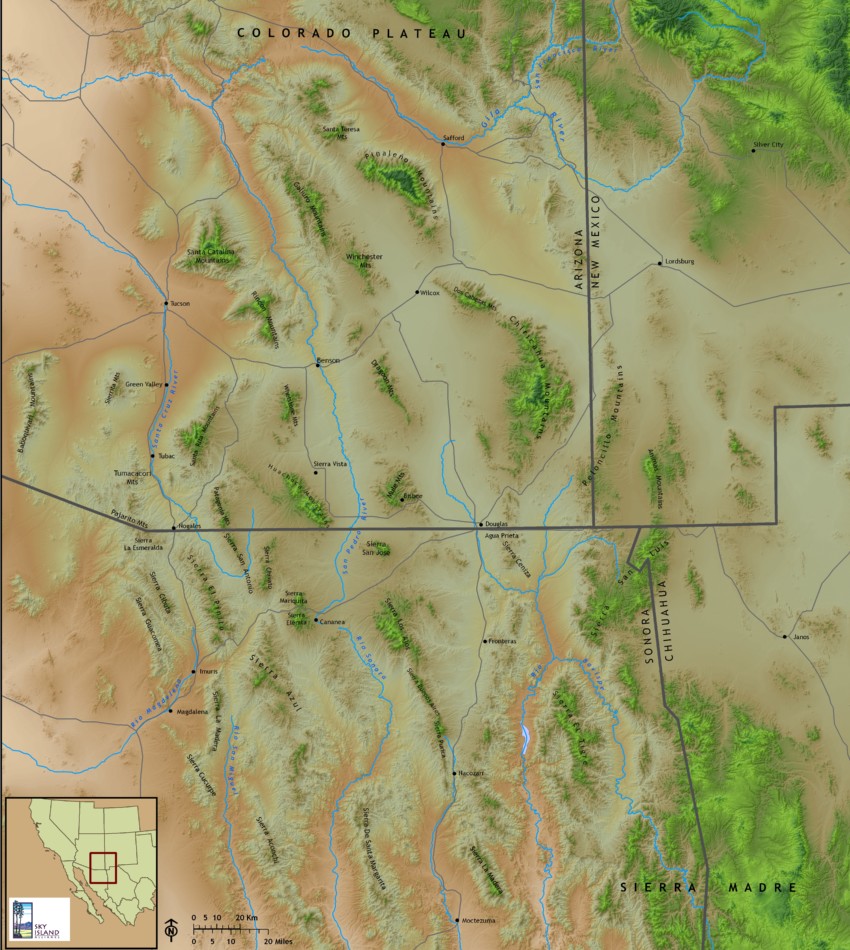

My phone pinged—my ride was here. Quickly, I grabbed my man-sized backpack and jogged up the escalator, catching two steps at a time. Exiting the upper level, I could tell just which ride was mine by the shadowy outline of naturalist Vincent Pinto slumped behind the steering wheel. I greeted him with a smile as he got out. When he wasn’t wearing his dark, broad-brimmed hat, Vincent’s head was usually covered with a bandana, which made him look a bit like a pirate. However, this pirate didn’t hoard rum or silver, but another increasingly rare commodity: nature. He and I were about to embark on a journey which would take us south into the heart of the Madrean Sky Islands, a region studded with 55 distinct mountain ranges, separated from one another by desert and grasslands—islands in a sea of grass and sweeping arid basins that are home to over 7000 species, more than half of the continent’s birds and creatures found nowhere else on Earth.(2) The Sky Islands extend as far as northern Mexico—we weren’t going to go that far south though. Nestled in the foothills between the Santa Rita Mountains and the Patagonia Mountains lay Raven’s Nest, the 42-acre nature sanctuary which Vincent and his wife Claudia had created a little under two decades ago.(3) This special place would be my home for the coming days. Accompany me on my journey as I revisit the Sky Islands. My hope is that it will serve as an introduction to its many beauties and some of the problems that threaten it.

Besides a naturalist, Vincent is also an ethnobotanist, wildlife biologist, amateur astronomer and wilderness survival instructor. He was first introduced to the Sky Islands in 1987, when he got a position at New Mexico State University as a wildlife graduate researcher and led a study on wild turkeys in the Peloncillo Mountains, on the border between Arizona, Mexico, and New Mexico. Vincent was amazed by the beauty and diversity of this particular Sky Island but also saw the negative effects that cattle and infrastructure were having on the region. He was shocked by the mentality that some locals had towards wildlife. Ranchers shot coyotes and Vincent’s own assistants in the field, local biologists, killed rattlesnakes for sport.

The Peloncillos had a profound impact on Vincent, and after spending a couple of years working in education on the East Coast, he returned to the Sky Islands in 1990. One region in particular, which he had seen from afar while doing his research in the Peloncillos, had sparked his curiosity: the Chiricahua Mountains, which sweep along Arizona’s southeastern border. Upon arriving in the Chiricahuas, it seemed like he had the entire range to himself. He wandered into a deep canyon and discovered an abandoned grotto; he decided to stay there indefinitely. After a couple of days, Vincent noticed that the winds had begun to pick up. Back then, he did not know Southwest too well and dismissed its warnings. One morning he discovered that his surroundings were covered in six inches of snow. To get to and from the grotto, he had to walk along a narrow ledge; if he slipped, he could seriously injure himself, even die. Nonetheless, he decided to hike up the adjoining mountain and by the time he was on his way down, the sun had disappeared behind the horizon. Luckily, there was a full moon that night, illuminating his path. Carefully, he traced his way back to the grotto, following his own ghostly imprints in the snow. When he got to the grotto, he discovered that the ledge had been frozen over. There was no way he could safely reach his shelter. Meanwhile, he was exhausted and freezing. Somehow, by a miracle that must’ve involved some desperate acrobatics, Vincent made it back to the grotto. In one of our conversations, Vincent told me that all he remembers is leaping and seconds later feeling the cold, cavern floor beneath him. Despite this frightening episode, Vincent fell in love with the Chiricahuas, which eventuated in him setting up his first nature sanctuary, Raven’s Mountain, in 1993.

Years later, in 2006, Vincent met Claudia Campos in Catalina State Park, near Tucson. Claudia had arrived in Tucson by chance while taking a break from her life as an esteemed international businesswoman. She fell in love first with Arizona (Vincent was very clear about this) and subsequently with Vincent. Together they set off to look for a permanent home. In 2008, their search brought them to the hills outside the town of Patagonia, where they settled into a house (they wanted to buy a property that already had a house to reduce their environmental footprint) overlooking a maze of arroyos interlaced with patches of mesquite bosque.(4) The land and vegetation were in very poor condition, largely due to overgrazing. The land had been used for ranching until it was fenced off in 1998. The subsequent owner kept horses, which like cows overgraze but will go so far as chewing the bark off trees. The couple had a challenging job ahead of them. Vincent set to resuscitating the microenvironment while Claudia designed Raven’s Nest’s layout and promoted the project to outsiders.(5) The result continues to attract and inspire people from far and wide.

I met Vincent and Claudia in 2016. My brother had been on a school trip to Raven’s Nest and returned enamored by the place and it’s two custodians. My parents decided to go back with the family, so we could meet them ourselves. We turned out to have a lot in common. To me, it felt like the couple embodied the very landscape that I had come to love. I was invited to return two summers later in 2018, and here I was again, buckled up and riding shotgun. Vincent and Claudia had been very busy the previous months. The former was in the process of writing a new book about biodiversity in the Sky Islands and had hosted Harvard researchers at Raven’s Mountain in the Chiricahuas. Still, he had taken the time to drive all the way up from Raven’s Nest to pick me up and give me a tour of his neighborhood. What is the architecture of this neighborhood and what are some of the creatures that inhabit it?

Sky islands are mountains which are isolated from radically different lowland environments. They can be found all over the world. Mount Kilimanjaro in the Afrotropical realm classifies as a sky island, ranging from Bushland at 800 feet to Rainforest at 1,800 feet, all the way to Arctic at 16,404 feet. The Caucasus in the Palearctic realm is also considered a sky island region and contains biomes ranging from subtropical lowland marshes and forests to glaciers and highland semideserts. However, what sets the Sky Islands apart from all the other sky islands is that it has 55 of them, the most on Earth. They are one of the most biologically diverse regions in North America, north of Mexico, ranging between 3,000 and over 10,000 feet in elevation. In a day, you can climb through the desert and scrubland habitats characteristic of central Mexico all the way up to fir forests characteristic of Canada.(6)

Because of their wide range of biomes and their location between the Rocky Mountains in the North and the Sierra Madre Mountains in the South, the Sky Islands have attracted over 7000 species of plants and animals from temperate as well as subtropical regions. They function as a highway for creatures traveling up and down the continent, but also for creatures migrating across from East to West. The Sky Islands have the lowest pass in the entire Rocky Mountain chain, affording creatures a relatively easy passage. Also, whenever they get hungry all creatures have to do is climb one of the many vertical grocery stores to the level at which their plant or prey resides, feed and continue onward until they reach the next Sky Island.

The Sky Islands have the most mammal species in the US—approximately 104, which is about 40 more than Yellowstone Park. They range between herbivores (pronghorns and bighorn sheep) omnivores (coatimundis and javelinas) and carnivores (coyotes). The region also has the greatest diversity of great cats in the US: mountain lions, bobcats, jaguars, ocelots, and possibly even jaguarundis.

Linking the Sky Islands by air and via the undergrowth are the Class Aves. Approximately half of the bird species found in the US and Canada are also found in the Sky Islands. Soaring high above the southern Island face are the raptors—turkey vultures, red-tailed hawks and the majestic bald eagle—while down in the canyon you may spot a quail with its young or a hummingbird hunting insects and sipping nectar from big, luscious cactus flowers. You’ll find as many as 18 species of hummingbird in the Sky Islands, which is more than any other part of the US. In addition, the Sky Islands have the most species of rattlesnake (nine) and reptiles (approximately 77) in the US as well as many endemic species, found nowhere else in the world.(7)

Contrary to some popular beliefs, Arizona is not a barren, lifeless desert; due to their extreme variation in landscapes the Sky Islands support a wide range of species, and scientists continue to discover new types of creatures. On the flipside, however, many creatures are also disappearing. A case in point is the jaguar. This magnificent, flecked cat from the tropics not so long ago ranged as far as the Grand Canyon in northern Arizona but is hardly ever seen in the US anymore. Many other species are finding it increasingly hard to find their footing in the Sky Islands. Climate change and development have turned these creatures into rarities and if something isn’t done soon, they might disappear from the US for good.

To my left the Catalinas were gradually receding; peaks blended into hills and soon we were enveloped by the desert. At first our conversation was about what I had been up to while I had been away from Raven’s Nest. However, after a while the topic shifted. Although Tucson had more or less felt the same to me, as we were driving out of the city I noticed it had spawned new, freshly plastered, blocky suburbs on its fringes. What’s more, huge dust clouds were whisking along the edges of these suburbs sucking up microscopic debris and dead vegetation. “Look at that dust haze,” Vincent said, pointing at the clouds of dust. “Filled with microplastics.” Dust hazes or dust devils, they’re not in the least uncommon in the desert, but as I looked down at the side of the road I noticed the plastics that filled the ditches and were choking the jumping cholla cacti growing in the basin to our right. Plastics too are no longer uncommon. That didn’t keep a shiver from creeping down my spine.

As we got closer to our destination, it dawned on me that one’s perception of an environment depends much on a person’s knowledge of and relationship with the land. If I hadn’t been sitting next to a local, experienced wildlife biologist and environmentalist, a lot of the signs that should cause alarm would’ve escape me. Before the town Patagonia, Vincent and I drove through a scenic stretch of golden grasslands that extended in both directions as far as the eye could see. The bronze effigy of a cowboy riding his horse stood on the crest of a hill on my right. It felt in place, the Lone Ranger riding off into the sunset. What I hadn’t realized was that most of the vegetation around me comprised an invasive species called buffelgrass which had been imported to the US to sustain cattle. I am familiar with the plant, which is originally from Africa, but would not be able to tell it from other species of grass, nor would I think to look for it here. I always thought of the Southwest as cattle country. I think that picture is true, but painfully incomplete. With too much livestock and virtually no natural predators but we to eat them (it’s legal in Arizona to hunt big cats like mountain lions even though they’re endangered) the land soon wears out; as a solution industry imported buffelgrass, which yields a lot more food for cattle and allows ranchers to ramp up production. In the meantime, buffelgrass permeates every bit of land it can sink its roots into, choking out all other vegetation—an all-too-common story of foreign species arriving in a new place and going berserk because it’s void of its natural clippers.

“In this land, cows rule,” Vincent told me. I laughed but quickly realized that he was being serious. All right, I thought. Let’s see just how much of that’s true. “What’d you mean?” I spoke.

“If a cow was to run onto the middle of the road, right here, as we were driving 80km an hour down the road, we wouldn’t just be paying for our hospital bills and the damage to the car—we would have to compensate the rancher for any damage done to his cow.” I wish in that instant I had pictured a cow hopping from the ER with a thick cast around its hind leg. That at least would’ve been a more entertaining thought. Instead, I didn’t really know what to think. “Meanwhile, cows are responsible for most of the region’s overgrazing, which in turn causes major erosion during the monsoon (flooding) season, when the rains carry away the earth’s most nourishing top layer.” I looked at the black angus cows in their paddocks, but no matter how I tried, I couldn’t make them grow devil’s horns or a moustache and goatee to resemble Faustian Mephisto—these weren’t malicious creatures. However, there was no doubt that these creatures, backed by industry, form a dire threat to the proliferation of Sky Islands biodiversity.

As we rode through the next bend, we entered a small glen with hills protruding steeply on either side, contrasted by the occasional arroyo, which formed a natural inclination in the land. We had exited the grasslands and entered the foothills of Patagonia, which are dominated by mesquite bosque. Like the grasslands earlier, I had passed through this area in 2018 on my way to Raven’s Nest. There was a stark contrast, however. “Welcome to the land where it hasn’t rained in a year,” Vincent spoke, gesturing forward with one outstretched hand, a rather macabre gesture accentuating the drouth that lay before me. In my experience, mesquite trees are naturally very arid-looking, draped in a dark, crusted bark. As such, I find it hard to tell whether a mesquite is in dire need of water or its usual dry self. However, the lack of fresh offshoot and the absence of juvenile vegetation in the undergrowth told me this land was holding out for dear life. It was nothing like the country I had seen in 2018, which had been dry but very much alive. The mesquite bosque is resilient, but if I had measured its pulse at that moment, I would’ve found an entity deeply asleep, dreaming of distal, rumbling clouds, gliding ever closer with the promise of fresh rain.

Strangely, as we approached the town of Patagonia, creek beds became reinvigorated with fresh growth. A trickle of water filled Harshaw Creek, and my heart leapt with joy. The town seemed more or less the same as I remembered it. The stores with their wooden façades surrounded the green park with tall trees, and to the side stood the post office, where we halted for a moment. Vincent had to pick up some mail. High above the town soared hawks and raven’s, riding on the warm afternoon thermals. We passed some construction workers on our way out of town. They were paving a smooth, new road that reminded me of a strip of liquorish. Occasionally, huge, bulky trucks would creep through town on their way to a mysterious location somewhere up-road. Vincent told me that he had been part of a large group opposing the construction of an open pit mine in the nearby mountains. They were successful and the operating company South32 (from Perth, WA) was forced to instead go underground.

South32’s Hermosa Project is still in the development stage of its Taylor deposit but is expected to be fully operational by the second half of the 2027 fiscal year, which should be somewhere around April 2028.(8) The company is investigating other deposits and plans to expand its operations in the near future. Backed by FA-41, short for Title 41 of the US’ Fixing America’s Surface Act, (9) which funds complex and allegedly critical infrastructure projects, South32 claims that it aspires to set a new standard for sustainable mining, strengthen the domestic supply chain of minerals critical to the country’s green energy future, grow the local economy, and improve the lives in the surrounding community.(10) However, judging by aerial photos, its location which is only five miles south of Patagonia, and the infrastructure that is being built to accommodate the increase in bulk traffic, I feared the negative effects might come to outweigh the project’s alleged benefits. Also, within their mandate South32 pays little attention to if not blithely skips over what I believe is Patagonia’s most valuable long-term commodity: its wildlife.

“No matter if you’re new to birding or are an avid birder looking to check rare species off your life list, Patagonia is your place.”(11)

Patagonia likes to flaunt its diverse range of birds, and with good cause. More than 300 species of birds, some very rare, have been sighted in the Patagonia area, attracting birdwatchers from all over the world. Patagonia even earned a place in the book 50 Places To Go Birding Before You Die.(12) American poet, novelist, and essayist James Harrison, famous for his trilogy of novellas Legends of the Fall, put it accurately when he called Patagonia “preposterously beautiful.”(13) Out of concern not just for wildlife but also for Patagonia as a tourist destination, I think a fair question would be: What does South32 do to offset its impact on wildlife inhabiting the Patagonia Mountains? If I’m to use the company’s website as a reference, while preventative actions are being undertaken to minimize risk of calamity to the town, South32 could be more a whole lot more involved in efforts to generate more habitat for wildlife and the protection of endangered species.

That leaves the creek. “The water you see isn’t rainwater,” Vincent said. “It’s runoff from the mine.” South32’s drilling causes subterranean water to come to the surface and fill the creek. To me, this gave rise to two major concerns. First, withdrawals caused by mining activities could deplete surface and groundwater supplies. Not only does Patagonia get most of its drinking water from the Mountains; the underground reservoirs also form a backup for flora and fauna in periods of drouth, like the one Patagonia was in now. Second, while there have been improvements to mining practices, it’s not uncommon for water to become polluted from mining. The SDWF states that there are four main types of pollution from mining; one of these, heavy metal contamination and leaching, directly involves two metals which have been discovered at Hermosa: silver and zinc. As water washes over the rock surface, it leaches out these metals and carries them downstream, which could have major health implications.(14) South32 states that to ensure safe and sustainable underground exploration, it has installed pumps to move groundwater away from the orebodies and treat it before redirecting it to Harshaw Creek. Most of the water, the company states, will sink back into the ground, evaporate, or be taken up by vegetation before reaching Patagonia. While this demonstrates that the company has undertaken initiative to minimize its impact on water and environment, one must ask if it’s acceptable for such large-scale water withdrawals to occur in the first place, and for the water to be sent down the creek and simply evaporate. Arizona has been in a long-term drought since 1994, with the precipitation decreasing by nearly an inch every decade.(15) To me, there’s something fundamentally wrong with seeing a creek flow while the surrounding country has been battling drought for not just a year but over a quarter of a century.

Upon its founding in 1898, Patagonia was a mining town, attracting prospectors from all over the US. Many sites were closed in ensuing years because they ceased to be profitable. Nowadays, the countryside is strewn with old, abandoned mineshafts, which are dangerous and pollutive. What will happen to Hermosa when its deposits dry out? The deposits are located below 750 acres of private land but may very well extend beyond this border outward into public land. If Hermosa one day became abandoned like all those other mines around Patagonia, surely it would be their Leviathan, the King of Poisoned Hollows. As Vincent and I left the town behind us, I thought about the many tourists that passed through Patagonia. Most wouldn’t have a clue about Hermosa or the water that was being emptied into Harshaw Creek. It would all seem natural to them, as it had seemed to me at first. I wondered if the people of Patagonia questioned what was going on in the hinterlands or ever stopped to look at the water in Harshaw Creek. Maybe they didn’t have time. Perhaps they had made their peace with it. “The mines promise economic growth and build a few new roads,” Vincent said. “People are easily persuaded.”

Half an hour later we arrived at Raven’s Nest. The best way for me to describe Raven’s Nest is as a maze. One could spend hours exploring the many trails that run across the property, sheltered beneath a canopy of bent mesquites. Every trail has its own name, relating to things that occur there. For example, there’s a trail all the way in the back of Raven’s Nest called Vulture, which leads into a small, windy canyon; another is called Red Tail Hawk; yet another is called Cotton Tail, and so on. The same goes for the various sites at Raven’s Nest. The sanctuary has safari tent grounds to the east, with an outdoor kitchen and picknick area, and several smaller camping plots in front of it. I pitched my tent at the site called Tarantula. In the center of this web of trails is the Discovery Center, which Vincent constructed from an old horse barn. As mentioned earlier, Raven’s Nest previous owner kept horses; Vincent wanted to have a minimal effect on the land, so he decided to convert the barn into what I believe is the heart of Raven’s Nest.

The stalls have cleverly been made to represent various regions of interest, from Sky Island biodiversity to history and the (material) culture of the Native American tribes that used to populate the area. Posters and infographics, terrariums and Sky Island treasures fill the space, bearing only the faintest hints that it was once a place of fly-swatting equines. Exiting the Discovery Centre through heavy wooden sliding doors, one has countless directions to go in and explore.

In the following days, Vincent showed me around Raven’s Nest and took me to some extraordinary natural areas including Patagonia Lake and the San Rafael Grasslands. During our tour, we continued discussing the problems threatening Sky Islands biodiversity and explored alternative forms of land management which are more sustainable and environmentally friendly. On our way to Raven’s Nest, we had identified pollution, drouth, invasive species, overgrazing, and mining. I wondered, what role does government play in all this? Over half of Arizona, which has an area of over 72,6 million acres, is in some shape or form government-owned. More than 30 million acres is public land managed by federal agencies like Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and Forest Service while an additional 9,2 million is managed by the Arizona State Land Department. One would hope that given the huge amount of land that they control, government agencies would set a good example of how to treat the land. However, Vincent believes that they leave a lot to be desired—and that’s putting it mildly. BLM and Forest Service manage land near Patagonia. They both go by the principle of multiple use, which combines wildlife habitat with recreation, cattle grazing, wild horses, and mining. According to Vincent, this is problematic. In his experience, the system of multiple use too easily turns into what he calls multiple abuse—a system in which particularly welfare ranching is prioritized over wildlife habitat and undermines conservation projects.

According to a 2022 study, around 85 percent of public lands in the western US are grazed by livestock.(16) Cows have a significant effect on climate change in three major ways: first, they are significant sources of greenhouse gasses; second, they defoliate native plants, trample vegetation and soil, and accelerate the spread of non-native species; third, they exacerbate the effects of climate change on ecosystems by creating warmer and drier conditions. Past disasters like the Dust Bowl have demonstrated the effects of European agriculture on the fragile Southwest ecologies. In fact, the land is still recovering from the disaster which occurred nearly a century ago. Agencies claim that they have learned from such tragedies and take climate change into account when creating new policies. Nowadays, a BLM representative stated in an interview, overgrazing is the exception, not the rule; ranchers are in it for the long run and together with the Bureau keep close track of drought conditions, adjusting the number of livestock down when after a ten-year period they go through on a permit renewal.(17) However, I’m of the opinion that what constitutes overgrazing can amount to a difference of opinion. Also, it seems inefficient to me to wait to readjust livestock numbers until after an exceptionally dry period. Should the Southwest even be in the livestock for the long run? I think Americans should be asking themselves whether they want to continue this harmful practice and not instead invest in more protected areas. It’s their public land after all. Public lands are immensely popular—over 500 million Americans visit them every year, benefiting from the outdoor activities that support both physical and mental well-being.(18)

A common argument in support of ranching and mining is that it has traditionally been part of Patagonia and the West for a long time. However, I believe that there is a huge flaw within this reasoning. Just because you’ve been doing something for over a hundred years doesn’t mean it’s a good thing. The image of ranchers herding cattle across the desert and grasslands has taken hold of popular imagination, but it does not consider the damage that lies in its wake. It’s estimated that ranching on public land amounts to over 500 million dollars in damage a year, which is approximately 26 times greater than the annual grazing fees collected by federal agencies. Conservation is not just in the best interest of wildlife. Besides benefiting people’s health, wilderness can be turned into a form of revenue (think of ecotourism, mindfulness, education, sustainable agriculture) which under the right stewardship is inexhaustible. Wilderness is what will save society from bankruptcy and more importantly its demise.

Raven’s Nest has offered an alternative perspective on the land and ways to manage it. To their great joy, since Vincent and Claudia bought their 42 acres in 2008, they’ve seen a significant increase in the biodiversity of native plants at Raven’s Nest, which in turn has fostered a greater diversity of wildlife. They’ve recorded 166 birds, several mammals, rare reptiles, amphibians, butterflies and other invertebrates. This diversity of species is thanks to their hands-on environmental policy prohibiting the use of heavy machinery. Besides monitoring wildlife, they engage in xeriscaping, which is landscaping with minimal use of water, to create wildlife habitat. They only work with drought-resistant native species, eradicating all types of invasive species (e.g., South African grasses) and using these as mulch to improve soil quality. The great thing about the native species is that long-term care is minimal, because the plants are accustomed to the land and its climate.

To ensure that the limited water available is distributed effectively, the couple has divided Raven’s Nest into two so-called water use zones. The first is called the Primary Zone and consists of native plants that need to be watered in their primary years and during times of drought. Vincent and Claudia planted them around the Discovery Center and their home. They provide shade and wind reduction, and are a source of fruit, nectar, pollen and other resources that are essential to a whole range of creatures. One afternoon I saw a hummingbird swoop past; I regularly spotted a pair of northern cardinals, and I was warned about one intrepid skunk that paid regular visits to the Discovery Center. The outer ring or Secondary Zone is composed of native species that persist much better in periods of drought, requiring only a little watering in the first year after which they’re on their own. The Vulture Trail is located in this much wilder part of Raven’s Nest, which like the Primary Zone attracts a lot of wildlife.(19) I was amazed by the sheer number of animal tracks that run through Raven’s Nest. Even though the land was parched, it was full of activity. The javelinas were the most obvious by the gorgeous mess they make, traveling in bunches and digging up earth with their thick snouts.

Besides wildlife, Raven’s Nest also manages its watershed. I followed Vincent as he showed me the various earthen berms he and volunteers had erected in previous years. A large arroyo makes its way along the southeastern edge of the property. During the summer, the arroyo is swallowed up by water and has extended as far as the Discovery Center. Using the system of berms, Vincent has tried to steer the water away from the campgrounds, slow it down and trap it in ponds to sustain species and prevent largescale erosion. It’s a passive form of water harvesting that complements the project’s active rainwater harvesting—during the huge summer storms, over 20,000 gallons of rainwater is collected from the roof of the Discovery Center and piped into Dragon Pond, whereafter it is pumped into two cisterns for storage.(20)

Another large contribution is the broad range of educative programs that Vincent has offered at Raven’s Nest. These include biodiversity tours, birding, sustainability courses, wilderness survival training, ethnobotany, and astronomy classes. These programs communicate the vision of Raven’s Nest to the outside world, which has resulted in academic researchers visiting Raven’s Nest and Raven’s Mountain in the Chiricahuas. It has also eventuated in me meeting Vincent, for which I’m very grateful. It’s through these kinds of meetings that new thought structures are interchanged and expanded. And therein lies the future of the Sky Islands. The more people come to realize how unique and beautiful the Sky Islands are, the more reason governments have to protect it. Nowhere on Earth will you find anything like the Sky Islands. Go online and experience it yourself! Have a look at the website of the Sky Island Alliance, or that of Ravens-Way Wild Journeys. On YouTube you can watch the shortened version of a documentary about the Sky Islands that features Vincent as the host.(21) While the responsibility lies with the US to protect this extraordinary landscape, it’s up to a global community of enthusiasts to advocate better policy.

After four days it was time to leave Raven’s Nest. On our way back to Tucson, Vincent and I reviewed everything we had discussed. It came down to this: The desert is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Many people think of Arizona as a barren desert where nothing lives or grows. With this in mind, they set out to treat it as if it were just that, empty. Through activities like welfare ranching, construction and mining, the land is gradually reshaped to fit that image, leaving nothing but a barren desert where nothing lives or grows.

This article has only been an introduction to the Sky Islands’ many crises. For example, I haven’t even gone into the US-Mexico Border that cuts straight through the region, causing tremendous disruption and destruction. The Sky Islands is one of the most diverse regions in the world and I think too few people know about it. If it’s to survive, more people should be introduced to its beauty and significance as a biodiversity hotspot. I encourage readers to learn more about the Sky Islands and spread the awareness of this amazing melting pot of species.

Bibliography

1. Tucson is a city in the south of the state of Arizona (southwestern US). It’s the second-largest city in Arizona, following the state’s capital Phoenix.

2. “Our Region,” Sky Island Alliance, accessed March 28, 2025, https://skyislandalliance.org/our-region/.

3. Here’s the website to Ravens-Way Wild Journeys: https://ravensnatureschool.com.

4. An arroyo is a dry riverbed that floods seasonally, usually during the summer in the monsoon season. Mesquites are a common tree in the Sonoran Desert, with dark crenulated bark and narrow, spiny branches. During the summer, they produce long seedpods that have a sweet taste when you chew them. Native Americans used these pods in their cooking.

5. “About Us,” Ravens-Way Wild Journeys,” accessed April 8, 2025, https://ravensnatureschool.com/about-us/.

6. “Meet the Sky Islands,” Sky Island Alliance, accessed April 1, 2025, https://skyislandalliance.org/our-region/the-sky-islands/.

7. “Ravens-Way Locations,” Ravens-Way Wild Journeys, accessed April 1, 2025, https://ravensnatureschool.com/ravens-way-locations/.

8. Check out the website, which even offers a virtual tour of the Taylor and Clarke deposits, only five miles south of Patagonia. The project claims it’s investing heavily in sustainable methods of ore extraction and contributing to the clean energy future of the US, extracting commodities like zinc and manganese required for batteries: https://www.south32.net/what-we-do/our-locations/americas/hermosa.

9. “Fast-41,” U.S. Department of Energy, accessed March 26, 2025, https://www.energy.gov/oe/fast-41.

10. “Why Hermosa?” South32hermosa, accessed March 26, 2025, https://south32hermosa.com/en_US/.

11. Dina Mishev, “World-Class Birding in Patagonia,” Visit the Sky Islands of Arizona, accessed March 26, 2025, https://visitskyislands.com/birding-in-patagonia/.

12. Chris Santella, Fifty Places To Go Birding Before You Die (New York: Steward, Tabori & Chang), 2008.

13. Harrison, who was a part-time resident of Patagonia, AZ, died of a heart attack on March 26, 2016, in Patagonia.

14. “Mining and Water Pollution,” Safe Drinking Water Foundation, accessed March 26, 2025, https://www.safewater.org/fact-sheets-1/2017/1/23/miningandwaterpollution.

15. “Climate of Arizona,” Arizona State Climate Office, Arizona State University, accessed March 26, 2025, https://globalfutures.asu.edu/azclimate/climate/#:~:text=The%20average%20long%2Dterm%20statewide%20annual%20precipitation%20is%2012.26%20inches.

16. J. Boone Kauffman et al., “Livestock Use on Public Lands in the Western USA Exacerbates Climate Change: Implications for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation,” Environmental Management 69 (June 2022), 1137-1152.

17. Ron Dungan, “Cattle Are a Part of Arizona’s History. Climate Change, Overgrazing Concerns Cloud Their Future,” KJZZ, published January 31, 2024, https://www.kjzz.org/2024-01-31/content-1869918-cattle-are-part-arizonas-history-climate-change-overgrazing-concerns-cloud-their.

18. “Public Lands,” Arizona Wildlife Federation, accessed April 1, 2025, https://azwildlife.org/public-lands#:~:text=Arizona's%20federal%20public%20lands—over,outdoor%20recreation%20and%20wildlife%20conservation..

19. “Conservation Practices,” Ravens-Way Wild Journeys, accessed April 2, 2025, https://ravensnatureschool.com/stewardship/xeriscaping/.

20. “Rainwater Harvesting Techniques,” Ravens-Way Wild Journeys, accessed April 3, 2025, https://ravensnatureschool.com/stewardship/rainwater-harvesting/.

21. “Biodiversity in the Heart of the Sky Islands 17-Minute Version,” Patagonia Area Resource Alliance, published November 16, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YdMtAFRjJ3Q&t=1s.