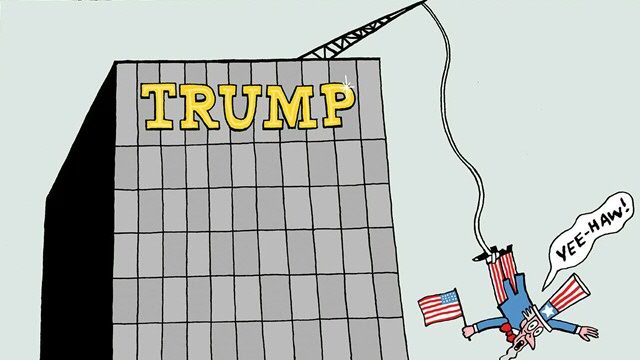

Sprong in het onbekende

Vergeet de laagopgeleide, boze, witte man. Donald Trump is president geworden dankzij een blinde drang tot verandering bij grote delen van het electoraat, zegt Eelco Runia. De ‘weldenkenden’ zijn in de geschiedenis vaker op die manier op het verkeerde been gezet.

Met de verkiezingszege van Donald Trump, afgelopen november, is de wereldgeschiedenis een mythe rijker: die van de laagopgeleide, boze, witte man die Trump zijn presidentschap bezorgde. Historicus, psycholoog en schrijver Eelco Runia noemt deze verklaring ‘kortzichtig’. ’Het past misschien bij het vooroordeel dat de Democraten toch al hadden, maar doet helemaal geen recht aan wat er speelt.’

In een opiniestuk in de NRC van 17 december haalde Runia de Italiaanse humanisten aan die rond 1500 en ook later in de 16e eeuw zich ‘totaal geen raad wisten met de “Trumps” van hun tijd: Cesare Borgia en paus Julius II. Die deden geen enkele moeite redelijk te zijn en hadden toch succes. Voor de humanisten waren het ongeleide projectielen, houwdegens: ze lieten zich meevoeren door hartstochten, waren lichtgeraakt en haatdragend, joegen mensen tegen zich in het harnas, waren ijdel en praalzuchtig en leken geen enkele boodschap te hebben aan hun welbegrepen eigenbelang.’ Volgens Runia inspireerde dit Machiavelli afstand te nemen van de humanistische weldenkendheid en een politieke leer te bouwen op het inzicht dat Cesare Borgia en Julius II succes boekten niet ondanks maar omdát ze zich niets gelegen lieten aan ragione (rede) en ruim baan gaven aan virtù (stoutmoedigheid).

‘Entitlement’

Dat de Democraten en andere ‘weldenkenden’ de overwinning van Trump niet zagen aankomen, komt door hun gevoel van wat Runia ‘entitlement’ noemt: het idee van de Democraten dat de verkiezingsoverwinning hen toekomt. ‘Dat is geworteld in het neoliberale denken dat in de jaren tachtig ontstond bij de liberals in Amerika en de sociaaldemocraten in Europa. Clinton, Blair en Kok zagen het neoliberalisme deels als onvermijdelijk. ‘De Democraten dachten dat het een kwestie van afwachten was tot demografische en culturele veranderingen hun beslag hadden gekregen om zeker te zijn van een soort permanente electorale meerderheid. Minderheden, jongeren en hoger opgeleiden zouden een zo groot electoraal potentieel voor de Democraten gaan vormen dat ze de macht min of meer in de schoot geworpen kregen.’ Dit idee bevat echter een flinke denkfout: mensen stemmen niet altijd voor hun welbegrepen eigenbelang, zoals de Democraten – en met hen vele anderen – veronderstellen.

Populisme

Runia verklaart het uit een elementaire behoefte aan verandering. ‘In mijn eerdere werk heb ik al gekeken hoe het kan dat de Eerste Wereldoorlog uitbrak, hoe revoluties ontstaan. Daarbij speelt altijd mee dat mensen soms hun rationaliteit opzijzetten in een blinde drang een grote sprong in het onbekende te wagen. Ook al kunnen ze op hun vingers natellen dat het niet in hun eigen belang zal zijn en het een hoop ellende, onrust en armoede met zich zal meebrengen. Het wagen van zo’n sprong in het duister is een elementaire, psychologische behoefte, die door historici consequent onderschat wordt.’

Dat mensen met Trump ook zo’n sprong willen wagen, komt doordat de overheid eenzijdig het ‘meritocratische contract’ met de burger heeft opgezegd. Het idee van de meritocratie houdt in dat de sociaal-economische positie van elk individu is gebaseerd op zijn of haar verdiensten: ‘Arlie Russell Hochschild schetst in haar boek Strangers in Their Own Land, over de Tea Party ideologie, het beeld van een rij geduldig wachtende mensen. Ze zien hoe anderen voordringen en hoe de overheid dat faciliteert en in zekere zin zelfs toejuicht. Dat levert een enorme agressie op jegens de overheid en de voordringers.’ Dat beeld, zegt Runia, is kenmerkend voor het huidige populisme, ook in Nederland en de rest van Europa. ‘Als voordringers wordt iedereen gezien waarop speciaal beleid wordt losgelaten: buitenlanders die met voorrang een huurwoning krijgen, vrouwen die opeens mannenbanen vervullen. Daardoor voelen populistische kiezers zich gepasseerd. De overheid houdt de brave burger wel aan het meritocratische contract, maar houdt zich er zelf niet aan en staat toe dat andere groepen dat ook niet hoeven. Dat is volgens mij de wortel van de populistische golf waarin we zitten.’

Regime change

Runia vindt het zijn taak als historicus om het huidige populisme zo bewust mogelijk te volgen. ‘Dat ik drie pop-up symposia beleg over populisme komt ook voort uit het besef dat we in een historische tijd leven. In mijn colleges probeer ik daar op allerlei manieren plaats voor te maken. Ik heb nu al op de rol laten zetten dat ik volgend collegejaar een werkcollege over regime change wil geven. Dus ik verwacht dat er wel wat gaat gebeuren. Het is nog maar de vraag of Trumppas over vier jaar inderdaad vertrekt.’ Dat klinkt onheilspellend. Gelukkig heeft Runia voor tegenstanders van het populisme in Nederland goed nieuws: ‘De opstelling van Wilders voorkomt dat hij een nog groter electoraat krijgt dat hij al heeft.’ Door voortdurend de racistische kaart te spelen, doet Wilders zijn electoraat en zichzelf eigenlijk tekort, terwijl het potentieel voor verandering gigantisch is.’

Eelco Runia (1955) is sinds 2003 universitair docent Moderne Geschiedenis en Theoretische en Intellectuele Geschiedenis aan de RUG. Hij studeerde geschiedenis en psychologie aan de Universiteit Leiden. Voor zijn proefschrift ‘De pathologie van de veldslag’ werd Runia in 1995 genomineerd voor een Gouden Uil. De rode draad in Runia’s werk is naar eigen zeggen ‘het schandaal van discontinuïteit’.

Tekst: Bert Platzer

Cartoon: Bas van der Schot

Bron: Broerstraat 5, het alumni magazine van de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen