Tentoongesteld in Aduard en Groningen

Momenteel zijn drie prachtwerken uit de Bijzondere Collecties van de Universiteitsbibliotheek Groningen te zien op tentoonstellingen in Aduard en Groningen.

Goed onderwijs

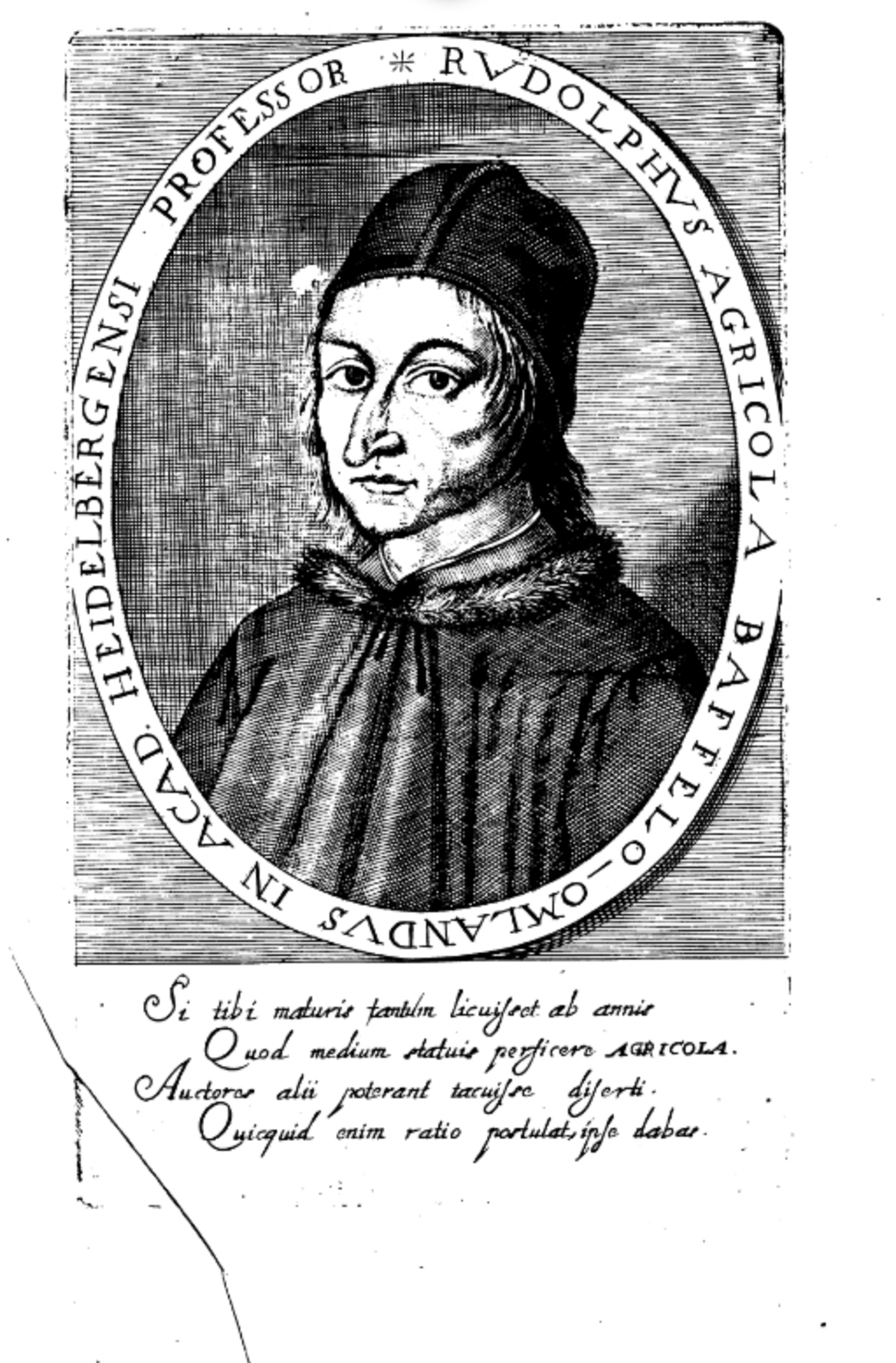

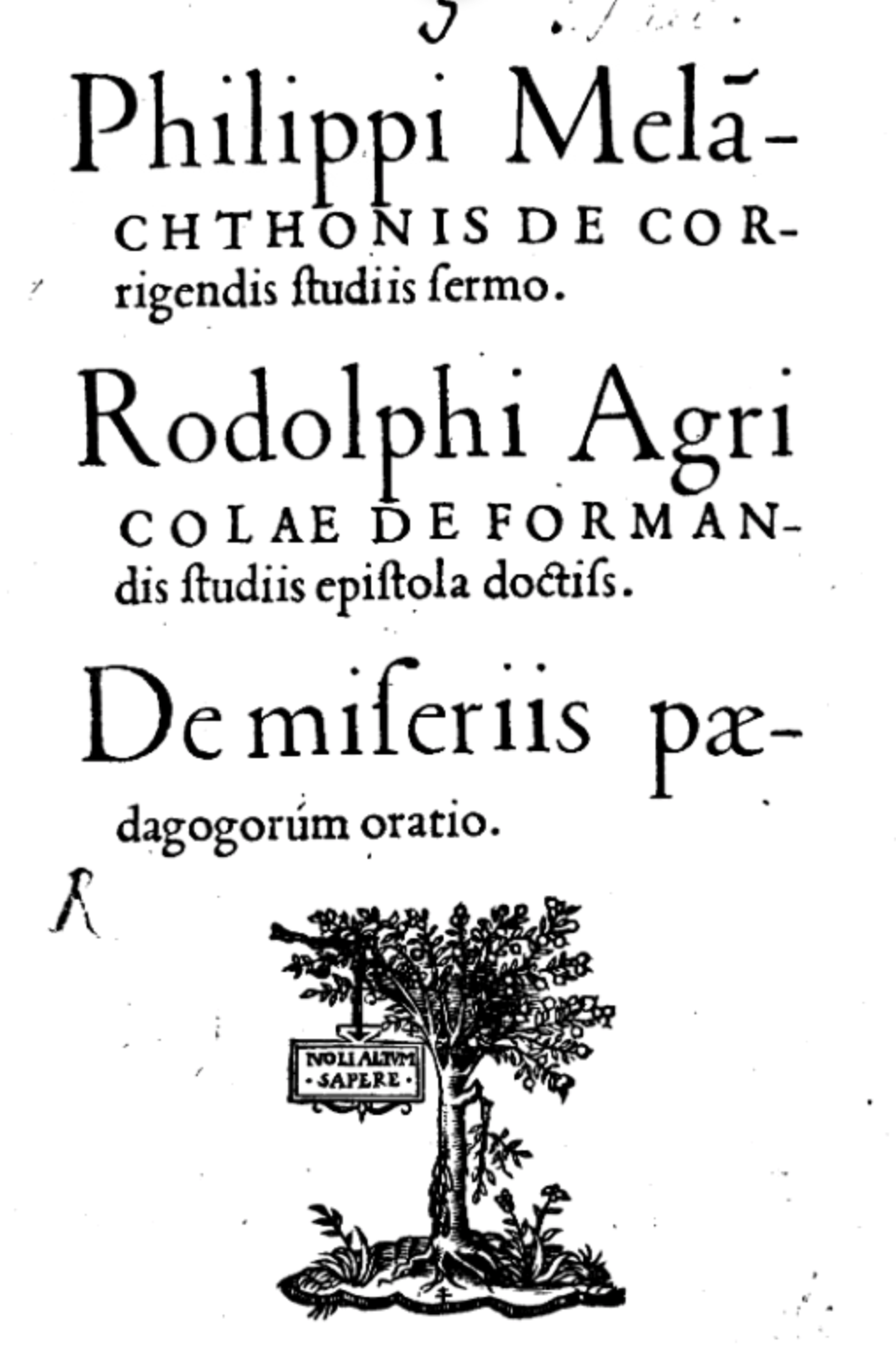

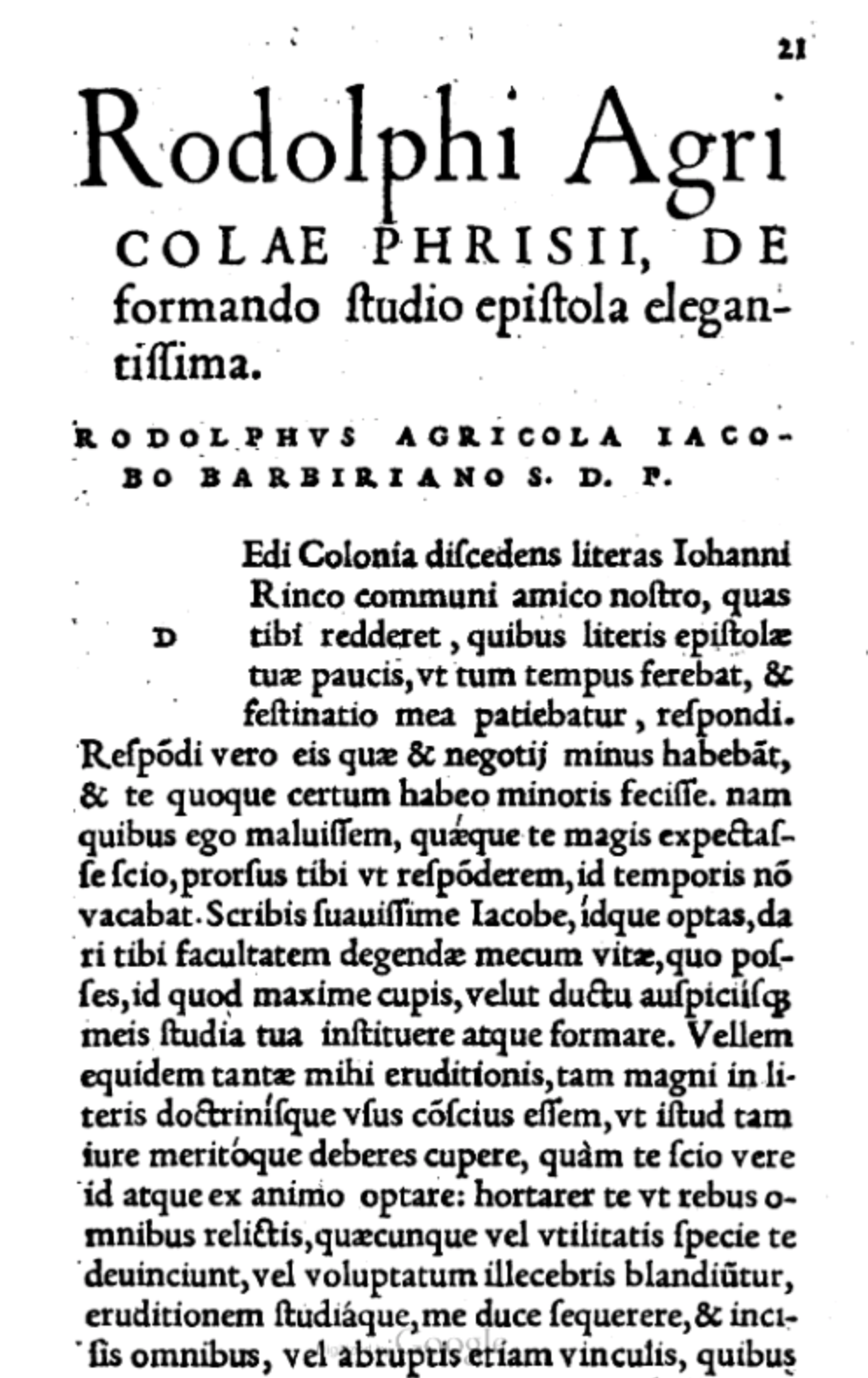

Kloostermuseum St. Bernardushof in Aduard toont een fascinerend boekje uit 1534 met teksten over goed onderwijs van Philippus Melanchthon (1497-1560) en Rudolf Agricola (1443-1485): Melanchthonis de corrigendis studiis sermo; Rodolphi Agricolae de formandis studiis epistola doctissima; De miseriis pædagogorum oratio.

Het boekje ligt opengeslagen bij brief 38 uit juni 1484 van Rudolf Agricola uit Baflo, een van de vroegste humanisten uit de Nederlanden, wiens geschriften in heel Europa invloedrijk waren. In deze brief zet Agricola zijn ideeën over onderwijs uiteen aan een vriend in Antwerpen. Hij onderstreept daarin onder meer het belang van creativiteit, d.w.z. het bedenken van iets nieuws en dat nalaten aan anderen. Louter het begrijpen van hetgeen je leest (door zorgvuldige literatuurkeuze) en dat goed onthouden (dankzij een getraind geheugen) is niet voldoende, meende hij. In de zestiende eeuw is deze brief maar liefst veertig keer gedrukt als een traktaatje over onderwijs: De formandis studiis (Over het vormgeven van de studie).

Het boekje is onderdeel van de expositie Van schrijfplankje tot schoolbord, onderwijs in Stad en Ommeland tussen 1200 en 1800. Ook om een andere reden is het boekje op zijn plaats in het kloostermuseum: Rudolf Agricola maakte deel uit van de zogenoemde ‘Aduarder kring’ of ‘Aduarder academie’, een gezelschap van noordelijke humanisten die in het cisterciënzerklooster in Aduard samenkwamen en discussieerden over oude en nieuwe cultuurvormen.

H.N. Werkman

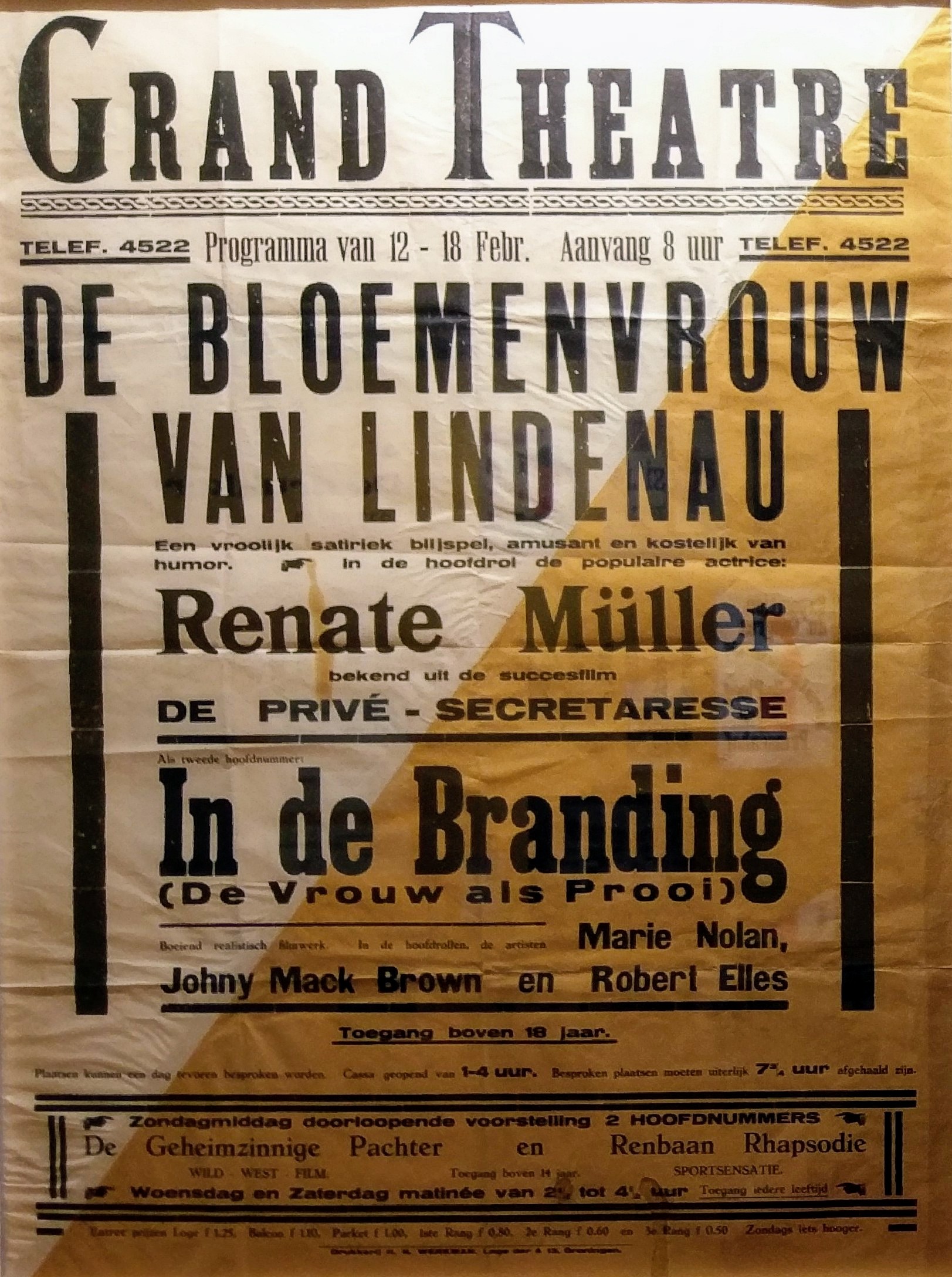

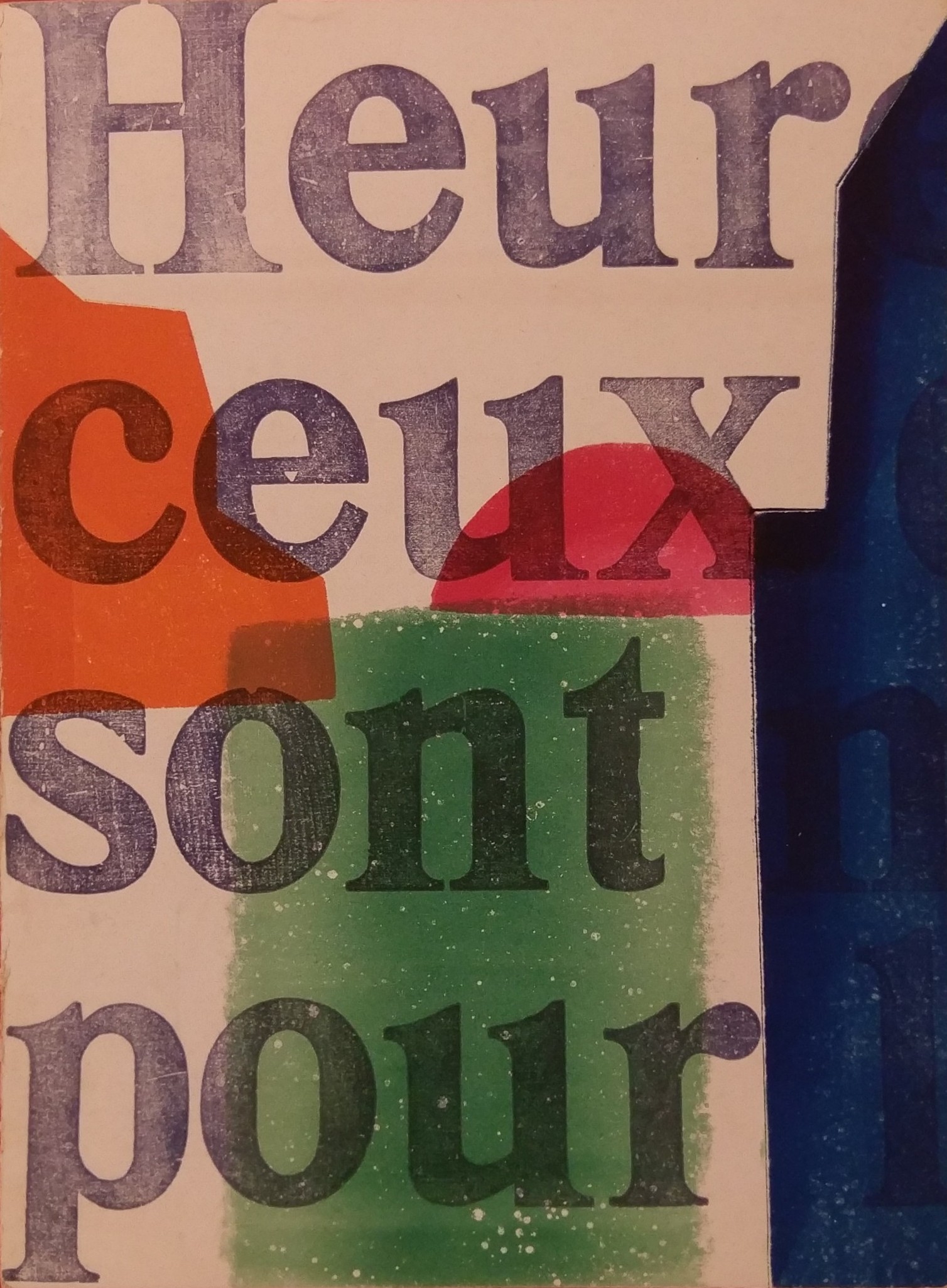

In GRID Grafisch Museum Groningen zijn het filmaffiche De bloemenvrouw van Lindenau (1931) en de herdenkingsuitgave Prière pour nous autres charnels van de clandestiene uitgeverij De Blauwe Schuit (1941) te zien in de expositie Werkmans Bovenkamer. Affiche en boekje zijn ontworpen en gedrukt door de baanbrekende, invloedrijke Groningse drukker-kunstenaar Hendrik Nicolaas Werkman (1882-1945). Beide worden geëxposeerd om te laten zien dat Werkman zich met dezelfde hulpmiddelen totaal anders kon uitdrukken.

Filmaffiche

Voor het filmaffiche (zijn gebruiksdrukwerk) paste hij hetzelfde lettertype toe, namelijk de houten biljetletter, als die voor het omslag van de Blauwe Schuit-uitgave (zijn oorlogsdrukwerk). De biljetletter gebruikte hij daarnaast ook voor zijn vrije kunst, de ‘druksels’. Ze illustreren hoe Werkman, die als commerciële drukker was begonnen, zich steeds duidelijker als kunstenaar ging manifesteren en hoe hij daarbij bijna moeiteloos schakelde tussen gebruiksdrukwerk, oorlogsdrukwerk en vrije kunst. In zijn vrije werk liet hij de betekenis van drukletters geheel los en benutte de letters en andere hulpmiddelen uit zijn drukkerij om een nieuw beeld te creëren van expressieve, vaak abstracte vormen, kleuren en de overgangen daartussen.

Werkman had met reden de naam van Renate Müller (1906-1937) als blikvanger op het affiche van het Groningse Grand Theatre geplaatst: zij was in de jaren dertig een van de grote Duitse filmvedettes, die ook in Nederland geliefd was. Werkman moest een truc uithalen om haar naam te kunnen drukken. In zijn letterkast ontbrak de u met umlaut. Daarom monteerde hij een los trema op de u. Het trema zou een terugkerend element in zijn drukwerk en druksels worden.

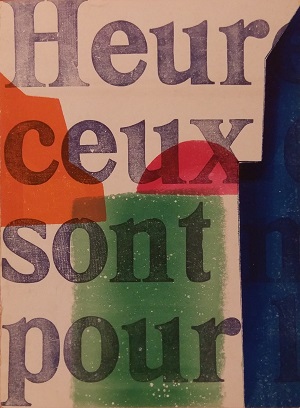

Herdenkingsuitgave De Blauwe Schuit

In 1941 produceerde de clandestiene uitgeverij De Blauwe Schuit haar vijfde drukwerk, het gedicht Prière pour nous autres charnels van Charles Péguy, in een oplage van 90 exemplaren, uitsluitend bestemd voor de vrienden van de uitgeverij. Met het gedicht, geschreven als een gebed voor de stervelingen, wilde de uitgeverij de slachtoffers van de Duitse inval in Nederland herdenken. De Blauwe Schuit nam alleen de eerste zeven strofen (van de 67) over.

Op het omslag drukte Werkman met de houten biljetletter fragmenten af van de eerste zin van het gedicht: Heureux ceux qui sont morts pour la terre charnelle (Gelukkig zij die gestorven zijn voor de aardse wereld). De woorden Heureux ceux qui sont morts zijn ook belangrijk omdat ze in de eerste achttien strofen van het gedicht worden herhaald. Met sjablonen en een handrol drukte Werkman onregelmatige vormen in vier verschillende kleuren af over een deel van de tekstfragmenten. Daarmee zette hij de expressie van de woorden kracht bij. De redactie van de uitgeverij ontleende het gedicht aan een bloemlezing uit het werk van Péguy die in de Franse afdeling van de Universiteitsbibliotheek Groningen was opgenomen (Morceaux choisis).

Attentie: vanwege de Corona-maatregelen zijn beide tentoonstelling beperkt toegankelijk.

| Laatst gewijzigd: | 15 december 2023 15:04 |

Meer nieuws

-

17 juli 2024

Veni-beurzen voor tien onderzoekers

Aan tien onderzoekers van de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen en het UMCG is een Veni-beurs van maximaal 320.000 euro toegekend. De Veni-beurzen worden jaarlijks toegekend door de Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk onderzoek (NWO) en zijn...

-

25 juni 2024

Hoe om te gaan met microplastics in ons dagelijks leven

Irene Maltagliati richt zich in haar onderzoek op de vraag hoe we ons meer bewust kunnen zijn van microplastics en ons gedrag kunnen veranderen.

-

17 juni 2024

De Young Academy Groningen verwelkomt zeven nieuwe leden

Na de zomer verwelkomt de Young Academy Groningen opnieuw zeven nieuwe leden. Hun onderzoek bestrijkt een breed scala van onderwerpen, variërend van spraaktechnologie tot de filosofie van ethiek en politiek en de polymeerchemie.