Not only the convents and monasteries have disappeared from Groningen

The convent of Yesse belonged to the order of the Cistercians. This monastic order was founded in 1098. That year, Robert of Molesme left his Benedictine abbey with a few disci-ples and founded a new monastic community on a site in the forest of the French Citeaux (in Latin: Cistercium). Robert found that observance of the Rule of Saint Benedict in the Bene-dictine monasteries was deteriorating. In particular, the obedience, poverty and humility mentioned in the Rule had been pushed into the background. Moreover, if we are to believe the sources, the vice of gluttony had crept into the monasteries.

From the Latin name for Citeaux the new monks were called Cistercians.

The order quickly expanded. In 1115, a daughter house was founded at Clairvaux. The first abbot of this daughter house was Bernard de Fontaines, a young Burgundian nobleman who had entered the order three years earlier. Under this Bernard of Clairvaux the order flourished. Many daughter houses were added, also outside of France. In 1160, the monastery of Klaarkamp (the Dutch translation of Clairvaux) was founded near Rinsumageest in Friesland. At the apex of its existence, it was home to 700 monks and covered a territory of 60 hec-tares. New houses were founded from Klaarkamp, including Aduard in 1192.

Bernard of Clairvaux proved to be an inspiring leader.

He soon developed a reputation as a saint whose words and actions inspired people to uphold sincere, time-honoured Christian values. His words therefore found a large audience throughout Europe—in the form of sermons, letters and many books on a wide range of aspects of the Christian faith. One sign of his popularity is the fact that many texts came into circulation that were claimed to have been written by Bernard, which obviously promoted their distribution.

His words were spread throughout Europe.

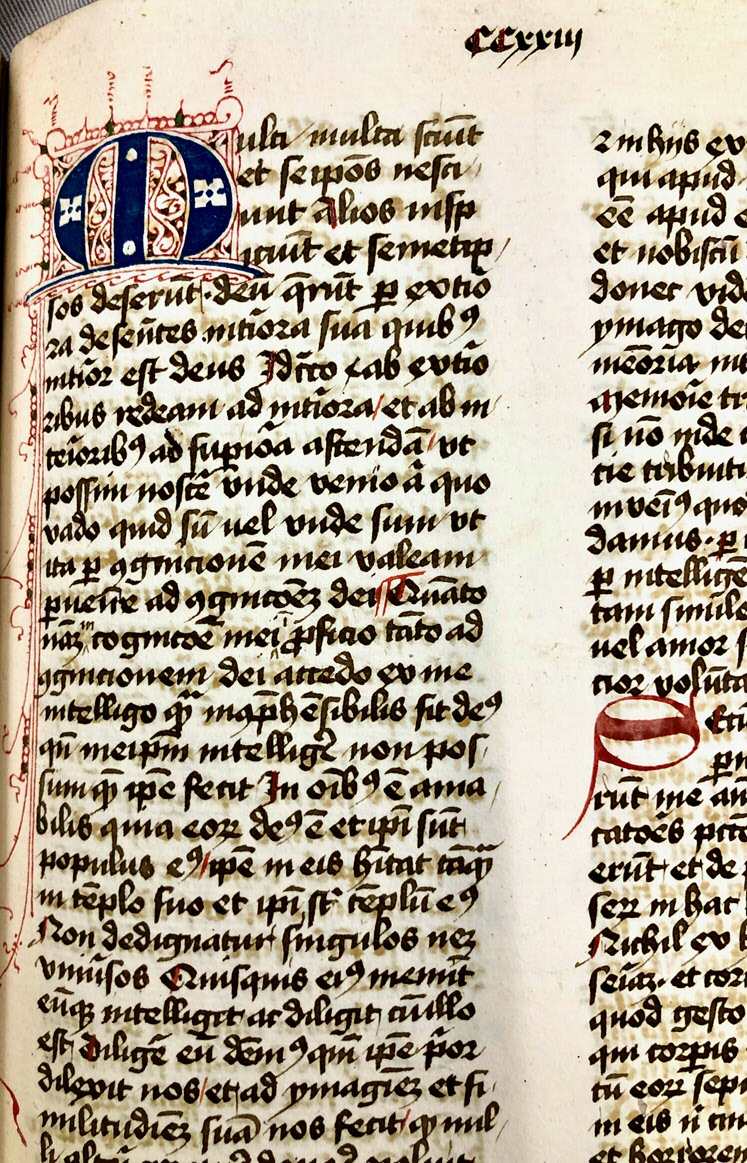

Residents of the city of Groningen and its surrounding regions also read or listened to the texts of Bernard. The University of Groningen Library owns several manuscripts and old prints containing texts by Bernard. They include a manuscript from 1455 in which someone had collected a variety of Christian texts by such authors as Bonaventure, Hugh of St Victor and the patriarch Augustine. The texts include Meditationes piissimae ad humanae conditionis cognitionem, i.e. “highly pious reflections on knowing the human condition” by “Saint Bernard the abbot”. At that time, these popular contemplations on human fate were attributed to Bernard, but we now know that he was not the author.

As an educated man of the church Bernard wrote in Latin.

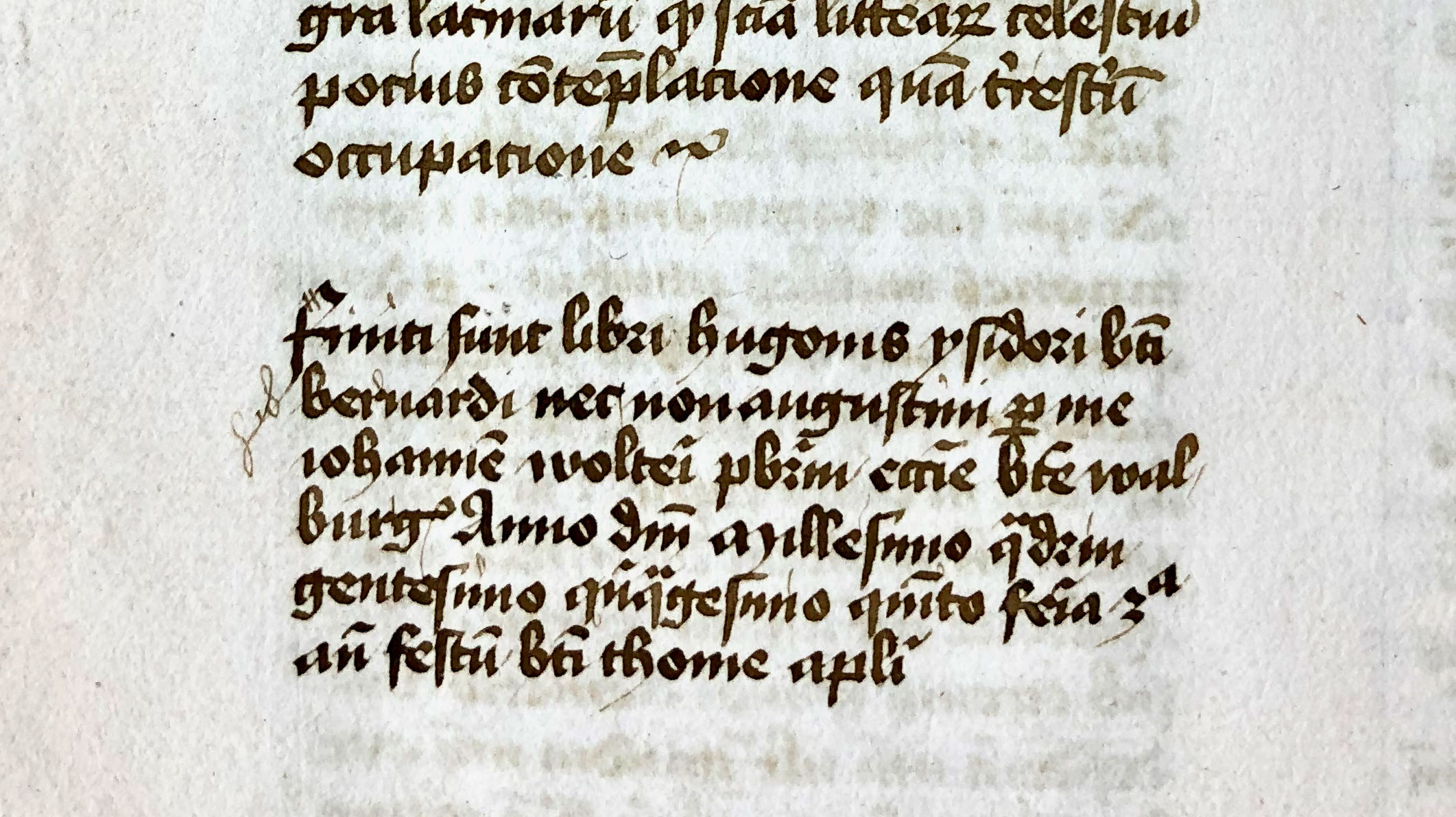

This was because Latin was the common language that every educated man in Europe had learned. Churches and universities used Latin as a working language until sometime in the 18th century and, in some countries, even the 20th century. In the schools of most European countries, Latin was not replaced as a working language until the 19th century. As a rule, women did not know any Latin, as only boys went to school and university. The Cistercian nuns of Yesse thus probably did not read the words of Bernard in the source language. Their brothers did, however, and not only in the monastery of Aduard, as evidenced by this one manuscript. On the last page, the scribe of this manuscript noted his name and location.

At the end, the scribe writes the following: Finiti sunt ... per me Iohannem Wolteri pres-byterum ecclesie beate Walburgis, i.e. “Completed ... by me, Johannes son of Wolterus, priest of St Walburg’s Church.” He even notes the date: Tuesday 18 December 1455. Appar-ently, this book was once in the library of the Walburg Church on the Martinikerkhof in Gro-ningen. Between 1619 and 1669, it found its way to the University of Groningen Library, as evidenced in our old catalogues.

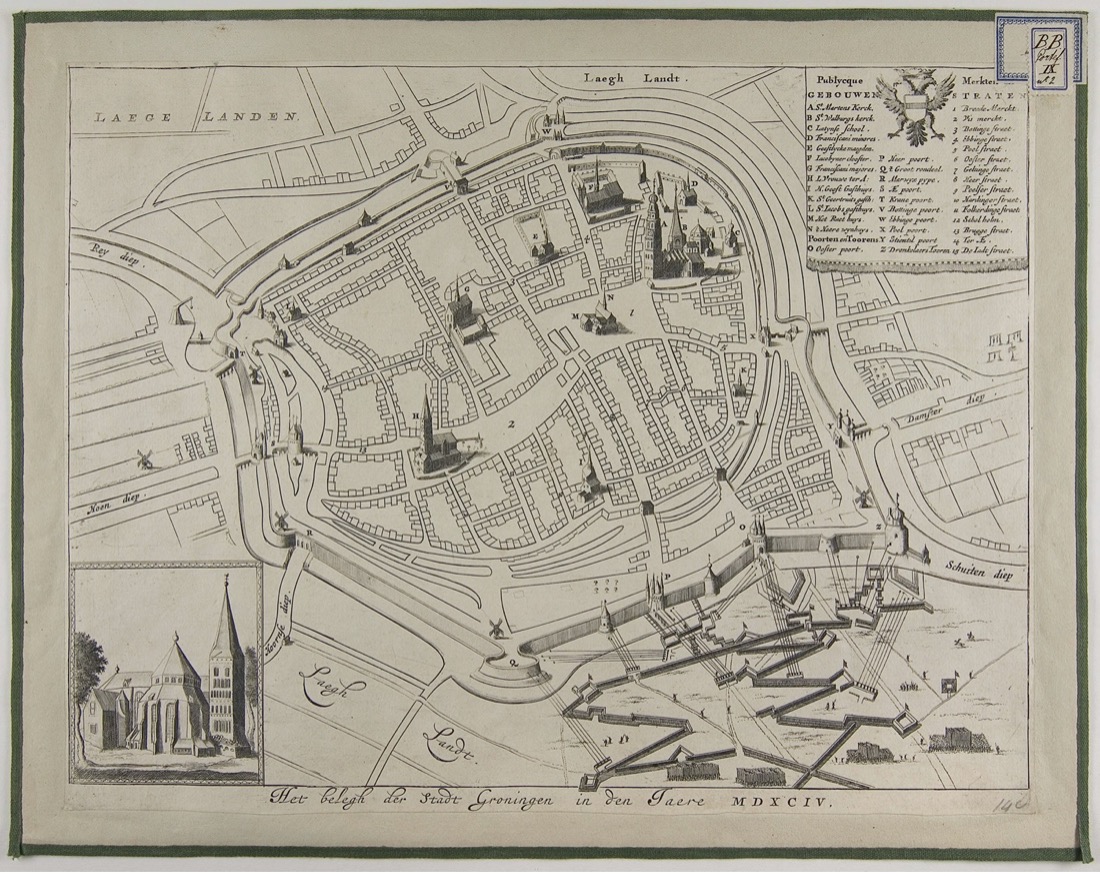

Like the convent of Yesse the Walburg Church has long since ceased to exist.

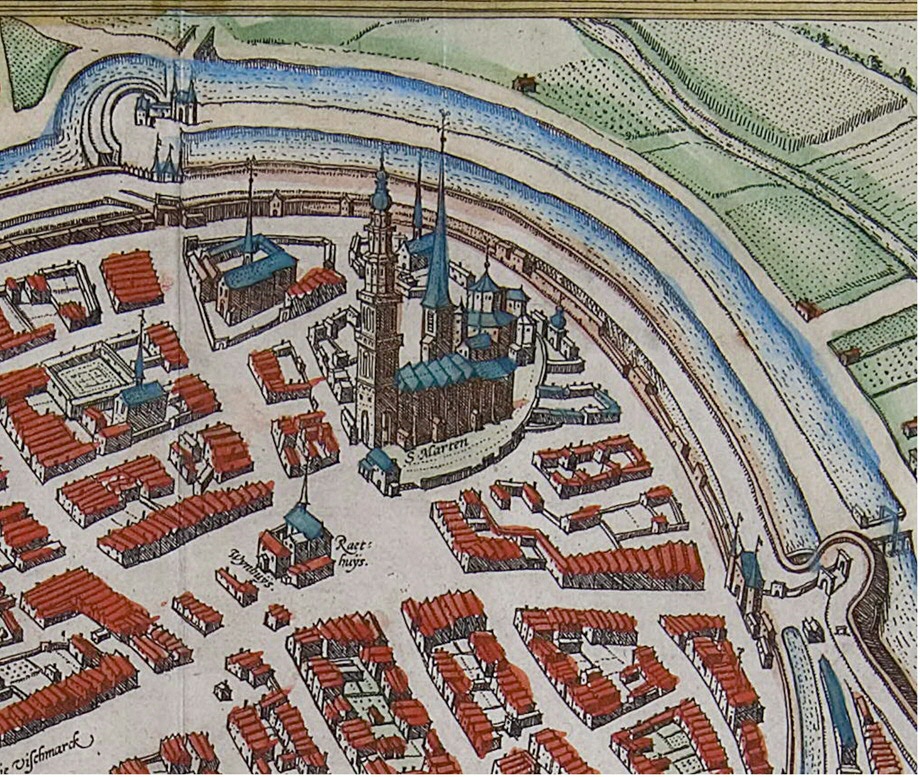

They disappeared around the same time: Yesse was dissolved in 1594, the Walburg Church was demolished in 1627. Now vanished without a trace, it was for centuries an impressive building on the Martinikerkhof. It was one of the city’s oldest brick constructions. Built as a chapel for Bishop Burchard in the early 12th century, this church was notable for its ‘round’ (octagonal) mid-section, with a rectangular chancel on the eastern side and a square tower on the western side. The cathedral in Aachen has a similar shape.

![The Walburg Church in L. Smids, Schatkamer der Nederlandsse oudheden [Treasury of Dutch antiquities] (Am-sterdam 1711), p. 374/375. In 1711, this church had indeed been “no longer in existence” for nearly a century. UBG UF 13](/library/_shared/images/bc/virtual-exhibitions/yesse/yesse-26.jpg)

Ubbo Emmius still makes prominent mention of the Walburg Church.

In his Rerum Frisicarum historia (History of Frisia), which he wrote between 1594 and 1616, Ubbo provides an extensive description of the city of Groningen. Of course, he mentions its churches as well: “In all, there are twelve churches, but only three parish churches. This is the oldest, with a round shape and solid walls, like a castle, dedicated to the young Walbur-ga, with an incessant spring of water continuously bubbling up, completely to the brim.” (ed. 1616, p. 19)

The dismantling of the Walburg Church began in 1594.

Lead was needed to make bullets in order to defend the city against Maurice, Prince of Or-ange, who sought to incorporate this last Catholic stronghold into the Protestant Republic of the United Netherlands. The lead roof of the church was used for this purpose. In 1611, the building collapsed in part, and this led to the decision to demolish the church completely, as it was no longer in use. The last remnants were removed in 1627.

Sources

- D.E.H. de Boer, Emo’s reis. Een historisch culturele ontdekkingstocht door Europa in 1212 (Leeuwarden 2011)

- M. Hillenga & H. Kroeze (red.), De middeleeuwse kloostergeschiedenis van de Nederlanden, III: Kloosters in Groningen (Zwolle 2012)

- T. Janson, Latijn. Cultuur, geschiedenis en taal. Dutch translation by A. & H. Pinkster (Amsterdam 2004)

- M. van Kruining, ‘De Sint Walburgkerk: de verdwenen ronde buur' in: Miniatuur/Vereniging Vrienden Martinikerk, 22.3 (2018), pp. 3-6

- J-F. Leroux-Dhuys, Cisterciënzer abdijen. Geschiedenis en architectuur (Cologne 1999)

- J. Loer, H.J. Kooi & K. Nitsch, Kloosterland. Land der Klöster: Fryslân, Groningen, Ostfriesland (Assen 2008)

- J. Stevenson, ‘Women’s Education’ in: Brill’s Encyclopaedia of the Neo-Latin World (Leiden 2014), dl. 1, pp. 87-99