Dit klooster floreerde onder Agricola's vader

Selwerd is nu een wijk in de stad Groningen. Menigeen zal er een sombere associatie mee hebben. Niet dat het een troosteloze woonwijk is, maar omdat aan de noordkant van deze wijk begraafplaats en crematorium Selwerdhof ligt. Juist op het terrein van de Selwerdhof bevond zich vroeger het benedictijner klooster Selwerd. Waarschijnlijk is het tussen 1150 en 1200 gesticht vanuit het klooster in Ruinen (Drenthe), maar harde bewijzen voor een concrete datum ontbreken.

Natuurlijk onderhield het klooster contacten met naburige kloosters, ook al behoorden die tot een andere orde, zoals Yesse. Af en toe zijn daarvan ook schriftelijke bewijzen bewaard gebleven. Zo weten we dat de abt van Selwerd in 1268 uitspraak moest doen in een geschil tussen een edelman uit Stad en het klooster Yesse. De abt moest oordelen of Yesse enkele bezittingen in Kropswolde legitiem had verkocht aan de abdij in Rottum. Hij gaf Yesse gelijk. De laatste abt van Selwerd, Henricus Lontzenius, noemt Yesse meermalen in zijn kasboek. Zo noteerde hij in 1562: “Ontfangen eyn koecke van Essen in gratiarum actionem 1 daler.”

Vanaf 1302 had Selwerd een band met Baflo, dat 14 km noordelijker ligt. In de Middeleeuwen speelden veel kloosters een belangrijke rol in de landbouweconomie en daarmee ook in de politiek van de Groninger Ommelanden. Hun inkomsten kwamen voor een belangrijk deel uit landbouw, veeteelt en het inpolderen en ontginnen van land. Dit geldt ook voor het klooster Selwerd. Concreet pachtte dit klooster in 1302 een boerderij in Baflo van de bisschop van Münster. De jaarlijkse opbrengst van deze boerderij was een van de inkomsten van het klooster.

De band met Baflo werd nog sterker in 1444, toen Hendrik Vries tot abt werd gekozen. Op dat moment was hij in Baflo persona, een belangrijke kerkelijke functie waarmee hij direct onder de bisschop van Münster viel. De overlevering wil dat Hendrik op de dag van zijn verkiezing tot abt ook het bericht kreeg, dat hij vader van een zoon was geworden: Roelof Huesman ofwel Rodolphus Agricola, die de eerste belangrijke humanist in de Nederlanden zou worden en een held van Erasmus. Hendrik zou hebben gezegd: “Goed zo, dan ben ik vandaag tweemaal vader geworden.” Strikt genomen was Agricola een onwettig kind, omdat z'n vader priester was en z'n ouders niet getrouwd. Agricola voerde de achternaam van zijn moeder (Huisman = boer = in het Latijn: agricola).

Bij Hendriks dood op 1 oktober 1480 zat Agricola als kersverse secretaris en ambassadeur van de stad Groningen aan zijn vaders sterfbed. Dat weten we uit een brief van Agricola zelf. Op 19 oktober schreef hij aan een vriend: “Mijn heer vader is eveneens gestorven, op 1 oktober. Moeder heb ik begraven op 7 april. Zou je niet zeggen dat dit lot mij door een vaste beschikking van God te wachten heeft gestaan: dat ik na zo’n lang verblijf in den vreemde naar ons vaderland terug moest keren om daar als pijnlijke vrucht van mijn thuiskomst te plukken dat ik binnen zo korte tijd beider ogen moest sluiten?”

De bloei van instellingen is ook bij een goede organisatie toch vaak afhankelijk van de personen die de organisatie uitvoeren. Hendrik Vries is hiervan een goed voorbeeld, want onder zijn leiding floreerde het klooster zowel religieus als economisch. Hij zorgde voor meer tucht en meer geld. Eén bron van inkomsten was de productie van handgeschreven boeken voor derden, dat wil zeggen voor religieuze individuen en instellingen en voor rijke seculiere patriciërs buiten het klooster die zich de aanschaf van zo’n kostbaar luxeproduct konden veroorloven en het ook konden benutten (lezen!).

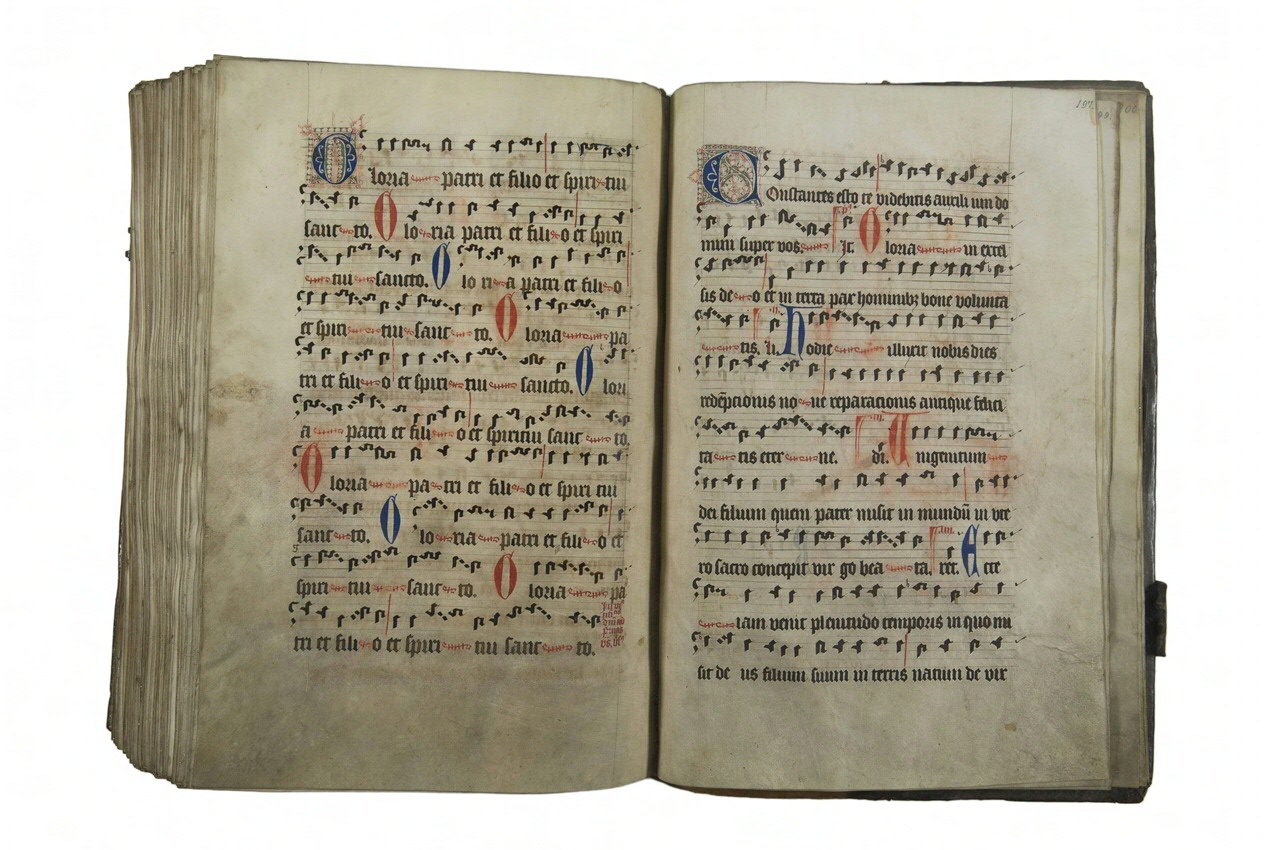

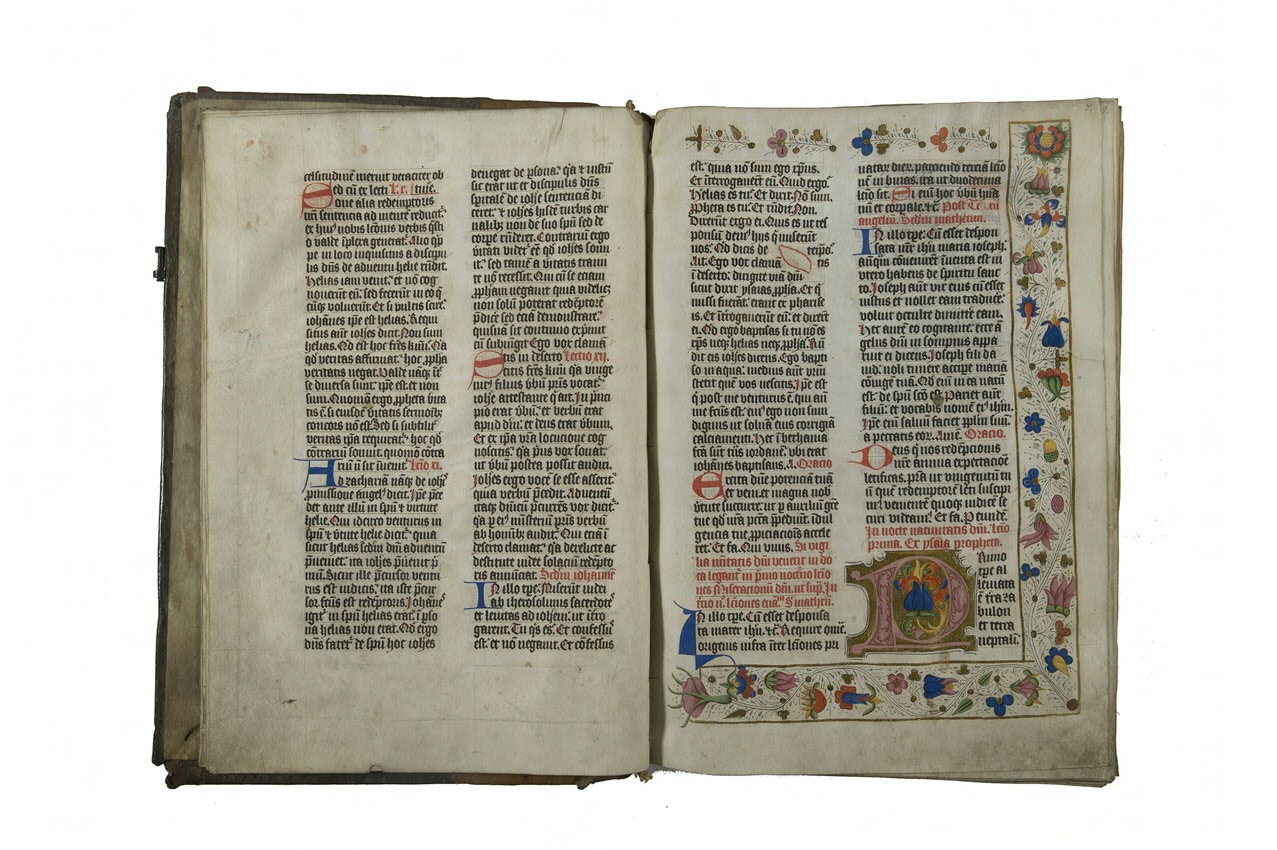

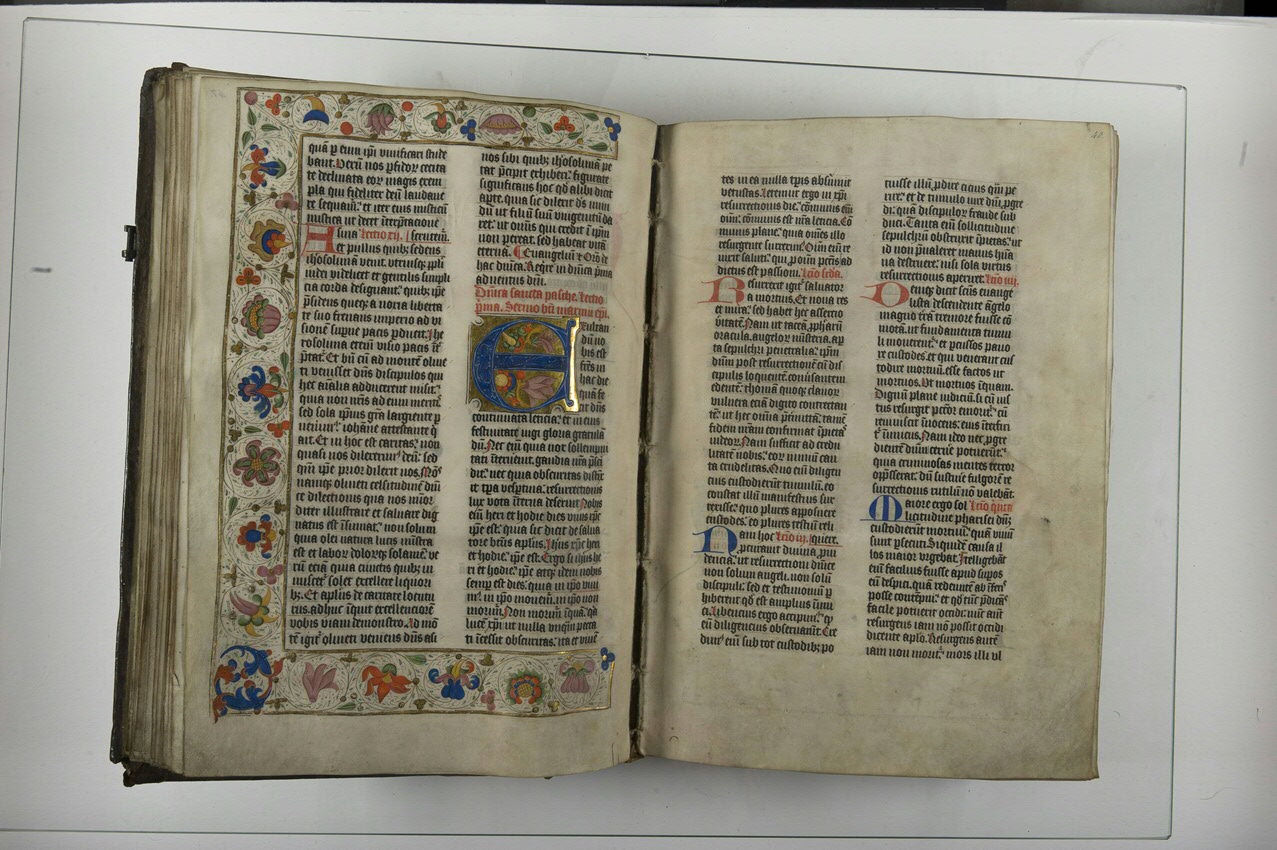

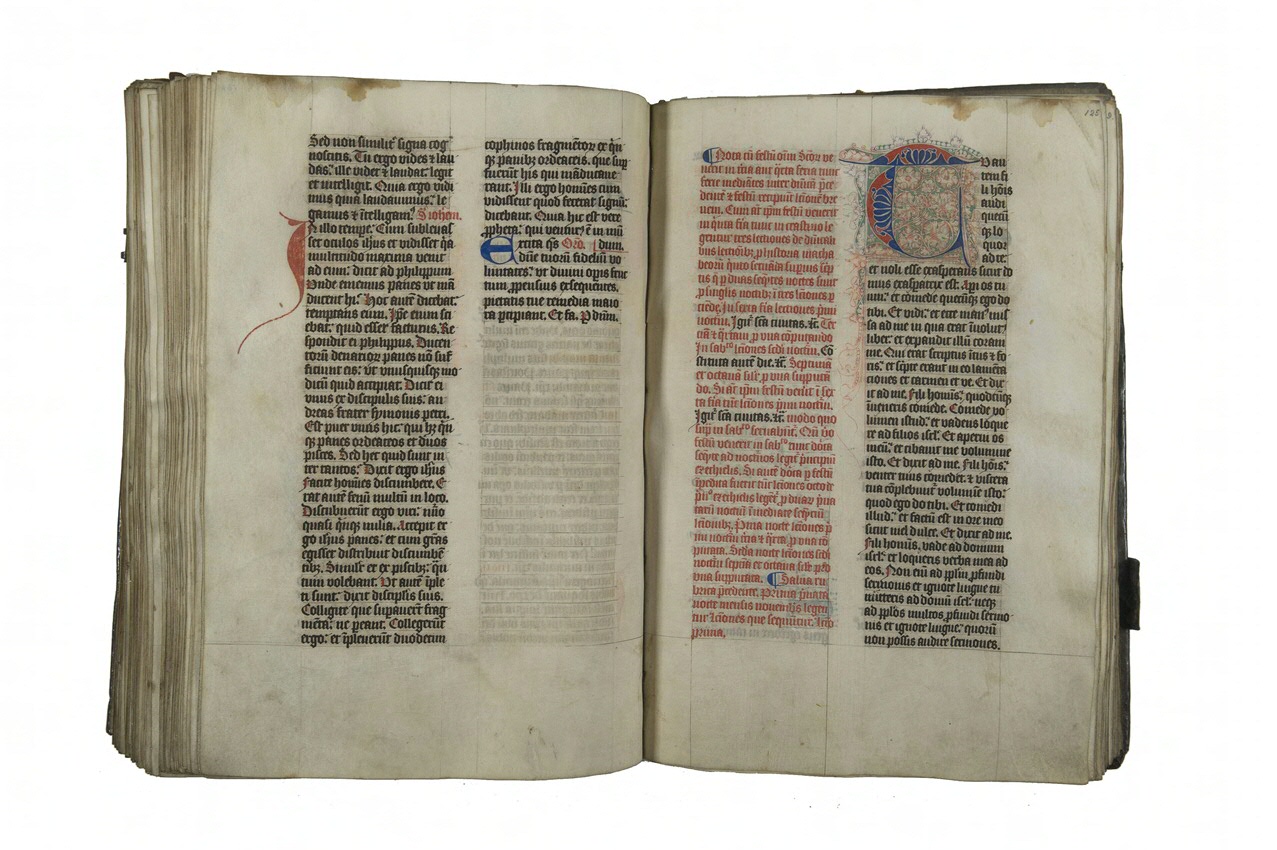

Onder abt Hendrik ontwikkelde het klooster Selwerd zich tot een belangrijk scriptorium. Een van zijn magnifieke vruchten is het grote lectionarium dat als HS 26 nu in de UB wordt bewaard. Een lectionarium is een voorleesboek. In dit geval bevat het de teksten voor de metten—het eerste gebed van de dag, nog voor zonsopkomst—van het hele kerkelijk jaar. Aan het einde zijn ook de te zingen teksten met melodieën (responsoria) toegevoegd. Dit boek werd dus gebruikt in de liturgie. Het bevat geen datum, maar op grond van de inhoud is vastgesteld dat het moet zijn geschreven tussen 1469 en 1488. De huidige band is iets later (begin 16e eeuw) aangebracht. Misschien wel in Selwerd, want er zijn aanwijzingen dat in dit klooster ook boekbindwerk werd verricht, al staat dat niet vast.

Overigens is dit boek incompleet. We kunnen zien dat een aantal bladen is uitgesneden. Dat zullen wel de mooist versierde bladen zijn geweest. Dit soort praktijken uit commerciële overwegingen zijn tot op de dag van vandaag helaas al te gewoon gebleken. Hoe dan ook bevat het handschrift nog steeds prachtig verluchte bladen. Kenmerkend zijn de weelderige, felgekleurde bloemen, bladeren, ranken en vruchten in de kleuren oranje, groen, geel, blauw en lila, vaak gecombineerd met goud. Ook typerend is het gebrek aan figuratieve voorstellingen.

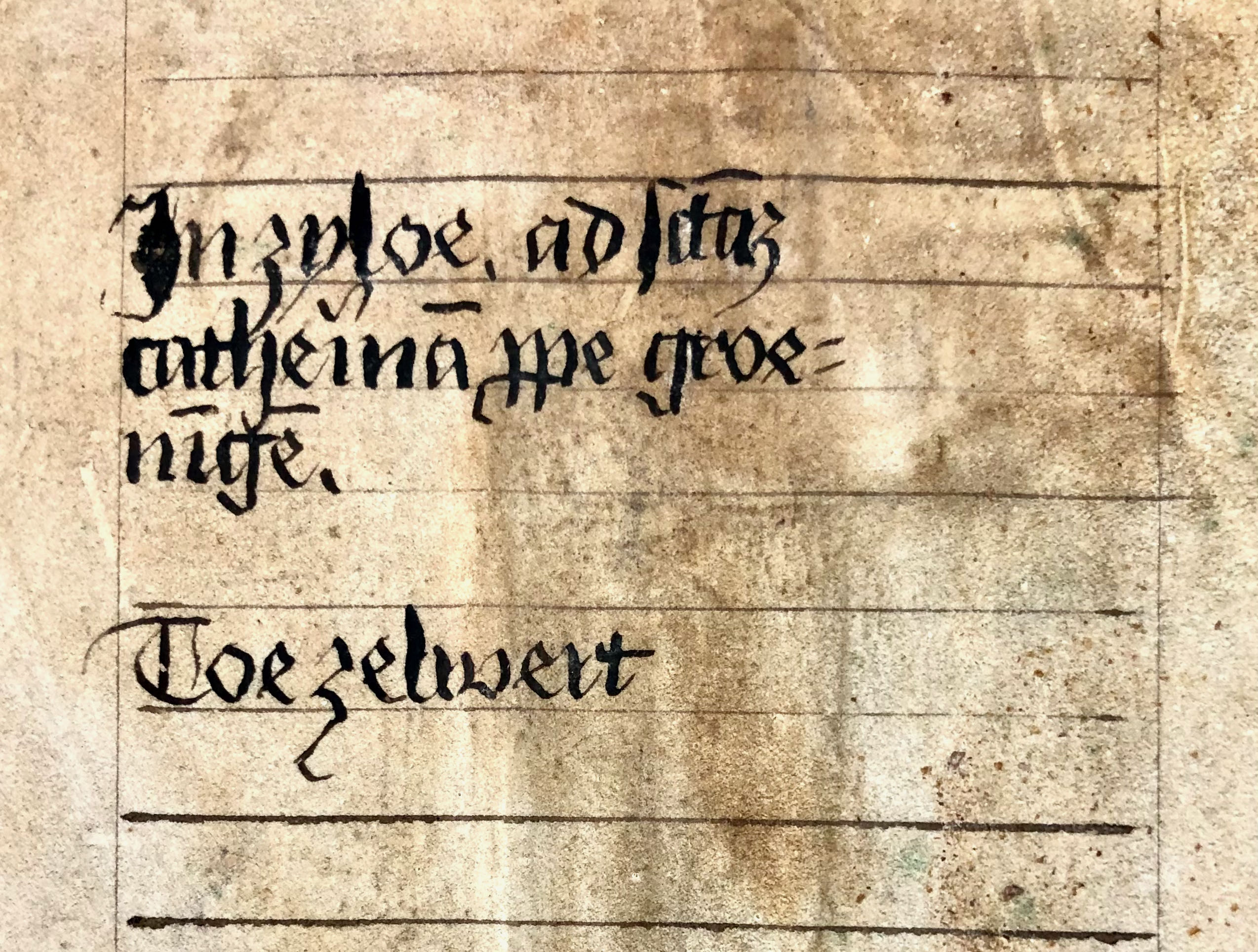

Bijzonder is dat in dit handschrift het eigendom is genoteerd op het dekblad voorin het boek (zoals eerder hierboven is afgebeeld). Daar staat geschreven: “In zyloe, ad sanctam catherinam prope groeningen. Toe zelwert.” Zyloe of Siloe was de Latijnse naam van het klooster Selwerd en de heilige Catherina van Alexandrië was de schutspatroon. Haar naam stond dus ook voor die van het klooster. De naam van degene die dit handschrift heeft geschreven, kennen we niet. Soms noemt zo’n kopiist zich wel bij naam, vaak in het colofon waarmee de tekst wordt afgesloten, maar dat is hier niet zo. Wel kennen we op deze manier de namen van vijf nonnen uit Selwerd, zoals Wendelmodis Roltemans en Agnes Martini (anno 1478).

Uit de periode 1470-1510 zijn nu ruim 40 handgeschreven boeken bekend die in Selwerd zijn gemaakt. Gaandeweg werd de uitvoering van deze boeken trouwens steeds soberder. De oudst bekende handschriften bestaan uit perkamenten bladen die vaak rijk zijn versierd, maar langzamerhand maakte men meer papieren boeken met hier en daar een rijkversierd perkamenten blad ingevoegd.

Het klooster Selwerd is opgeheven in 1595. Op dat moment verbleven er nog zo’n 30 nonnen. Tien jaar eerder had het klooster al een gebouw in de stad Groningen aangekocht als extra refugium (dependance), omdat het reguliere refugium—het Vrouwe Sywenconvent, dat ernaast lag op de plek waar nu het Academiegebouw staat—bij sluiting van het klooster niet aan alle ingezetenen een plaats zou bieden. Blijkbaar daagde dat onvermijdelijke einde dus al in 1585. Het extra refugium deed later dienst als rechtbank en is nu onderdeel van de RUG (Oude Boteringestraat 36). Het klooster Selwerd is gesloopt in 1601.

Bronnen

- F. Akkerman & A. van der Laan, Rudolf Agricola. Brieven, levens en lof van Petrarca tot Erasmus (Amsterdam 2016)

- F.J. Bakker, R.I.A. Nip & E. Schut, Het kasboek van Henricus Lontzenius, de laatste abt van het klooster Selwerd, over de jaren 1560-1563 (Assen 2003)

- C. Damen, Geschiedenis van de Benediktijnenkloosters in de provincie Groningen (Assen 1972)

- Jos.M.M. Hermans, Middeleeuwse handschriften uit Groningse kloosters (Groningen 1988)

- Jos.M.M. Hermans, “Laatmiddeleeuwse boekcultuur in het Noorden: zoeken en vinden” in: Boeken in de late Middeleeuwen [...], ed. Jos.M.M. Hermans & K. van der Hoek (Groningen 1994), 221-228

- A.S. Korteweg, “Tellen en meten: Noordnederlandse getijdenboeken in de database van het Alexander Willem Byvanck Genootschap” in: Boeken in de late Middeleeuwen [...], ed. Jos.M.M. Hermans & K. van der Hoek (Groningen 1994), 313-324

- I. Smit & M. Heidema, Wandelen in middeleeuws Groningen. Op zoek naar kloosters en refugia (Haren 2015)

- De wereld aan boeken. Een keuze uit de collectie van de Groningse Universiteitsbibliotheek (Groningen 1987)