The sisters of Yesse had brothers in Aduard

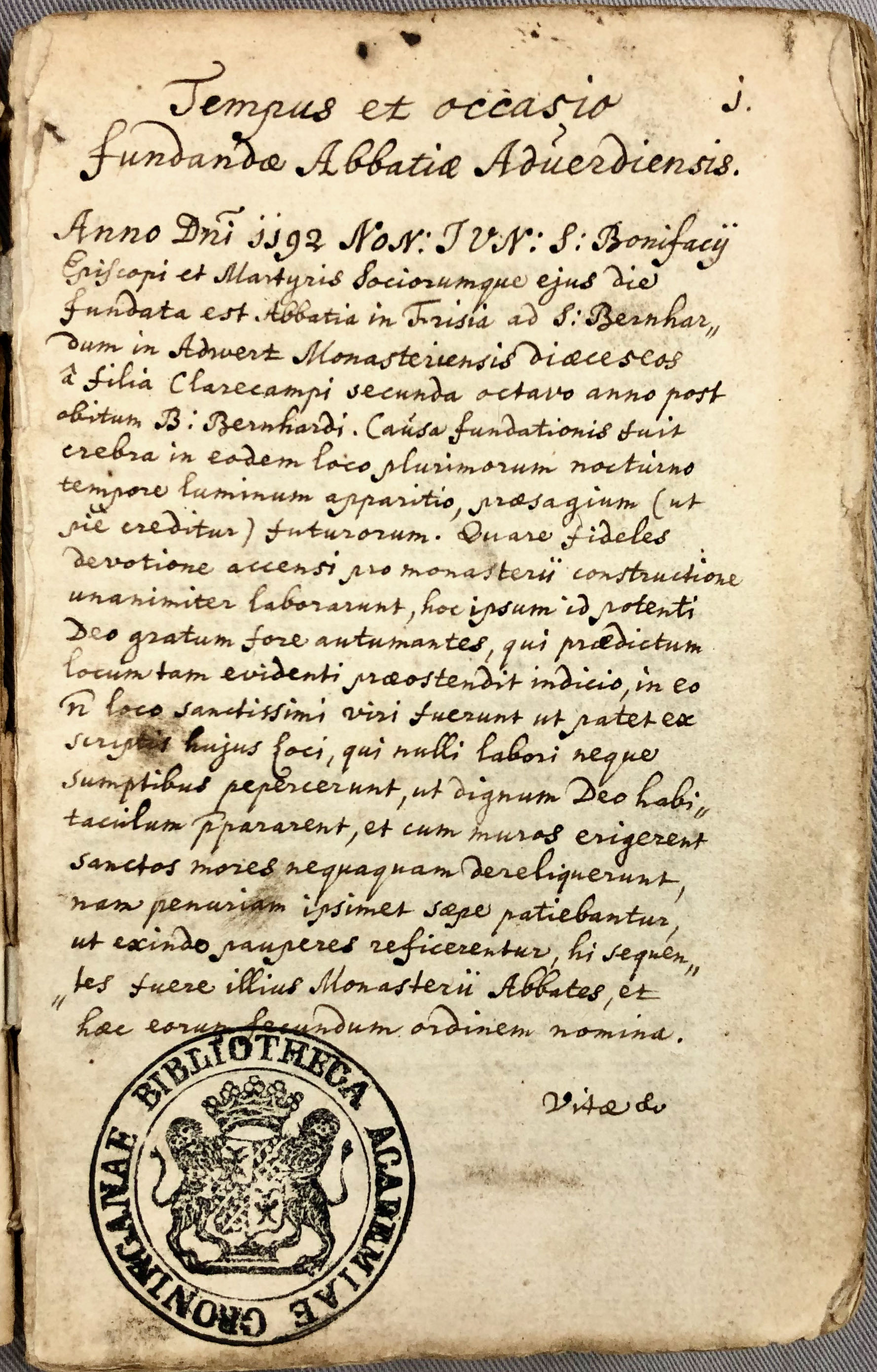

The convent in Essen was founded in 1215. At that time, a monastery also belonging to the Cistercian order was already in existence fifteen kilometres to the north-west: St Bernard’s monastery in Aduard. It was founded in 1192 as the first Cistercian monastery in the region of Groningen. In its heyday, Aduard was the largest monastery north of Paris, with around 6,000 hectares of land. It was one of the ten largest Cistercian abbeys in all of Europe.

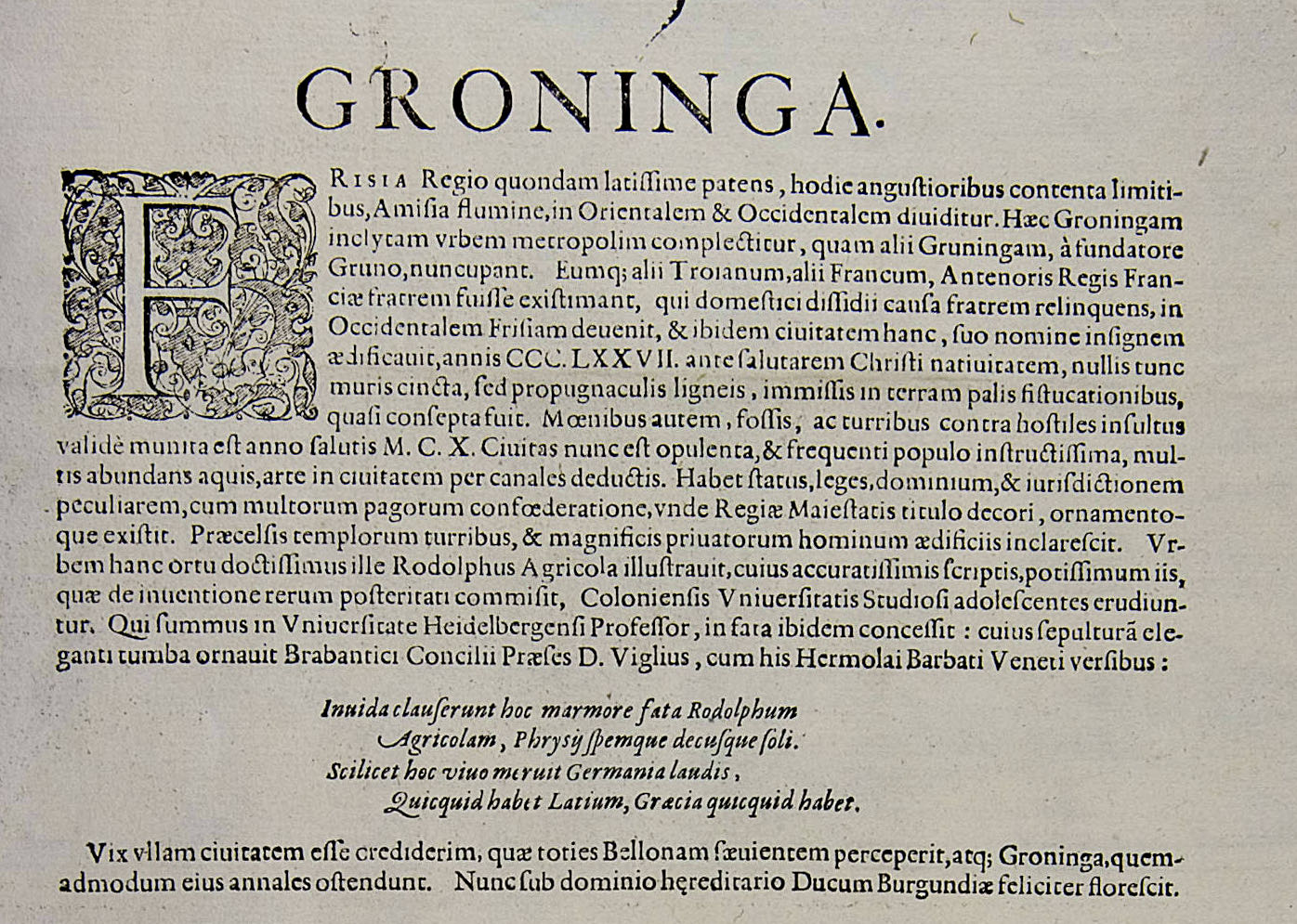

We do not know what the monastery looked like or how it was constructed. The only ‘image’ of it can be found in this overview of the city of Groningen from 1576, in which the colossal monastery church of Aduard is visible on the horizon to the left of the city. The monastery is also identified by name: Groot Adwortteim Clost(er)—it was prominent enough for that, but not much of it is visible here. Out of necessity, therefore, any reconstruction must be based on sporadic excavations, on comparisons to Cistercian convents and monasteries elsewhere in Europe and on comments in the chronicle of the abbots of Aduard. Any visual representations must be based on theory and speculation.

![Colophon in the Cartularium van het Aduarderzijlvest [Register of the Aduard water district], 1534 (p. 137). UBG uklu HS ADD 302](/library/_shared/images/bc/virtual-exhibitions/yesse/yesse-42.jpeg)

As a large landowner, the monastery was an important economic player. For example, it had a major influence on water management in north-western Groningen. This is evidenced by the cartularium (register) of the Aduarderzijlvest (Aduard water district). This register contains documents from the years 1382-1492, with supplements from 1540-1598 and 1627. The following appears on p. 137: “This book was written by order of Lord Johan Bellinckhoven van Rees, cellerar of Aedwert, for the benefit and use of the general aldermen and water-district judges of Aedwert water district. In the year of our Lord 1534.” Johan van Rees was the cellerarius (economist) of the monastery and chairman of the water dis-trict.

The monastery of Aduard had six daughter houses.

They included Yesse and three other convents. Although Yesse was not founded from Aduard, it would soon come under its supervision. This was probably the case as soon as 1220, after the abbot of the Cistercian monastery in Heisterbach had paid two visits to Yesse (in 1218 and 1220) in order to assess whether it met the criteria for admission to the order. On these visits the monk Caesarius accompanied his abbot. His famous Dialogus miraculorum (Dialogue on miracles) from 1219-1223 is the oldest source in which Yesse appears.

One duty of a mother house is the visitation of daughter houses.

A tour of the Cistercian convents and monasteries was particularly complicated. They were often located in areas that we would now consider idyllic or rural—on a lovely coastline or standing free in the forest. This was the approach of Bernard of Clairvaux. Convents and monasteries were founded in areas that demanded struggle—a struggle against the devil. In medieval interpretations, Satan reigned particularly in inhospitable and unexploited areas. It was for this reason that a monastery was founded in the former salt-marsh landscape in which the islands of Middag and Humsterland had existed shortly before that time. This monastery in Adewerth, or Adworttein, would become an intellectual centre.

In 1295, the learned Emmanuel de Secola, the Bishop of Cremona and a Master of Laws graduated from the Sorbonne in Paris, stood at the gate in Aduard. He knocked on the door, and he would remain there for the rest of his life. A few years earlier, the crusader Richard de Busto, a graduate of Oxford and the Sorbonne, had come there as well. On the way to the Holy Land, he had encountered a hermitess who prophesied to him that he was to become a great monk in Frisia. He would do just that. For thirty years, he would astonish everyone with his healing hands and gifts of prophesy. The grave sites of both Richard de Busto and Em-manuel de Secola became important destinations for pilgrims. This enhanced the importance of Aduard. During his visit to Pope Benedict XII, Abbot Frederick (1329-1350) tried to enhance its importance even further by having them canonized, but his efforts were unsuccessful.

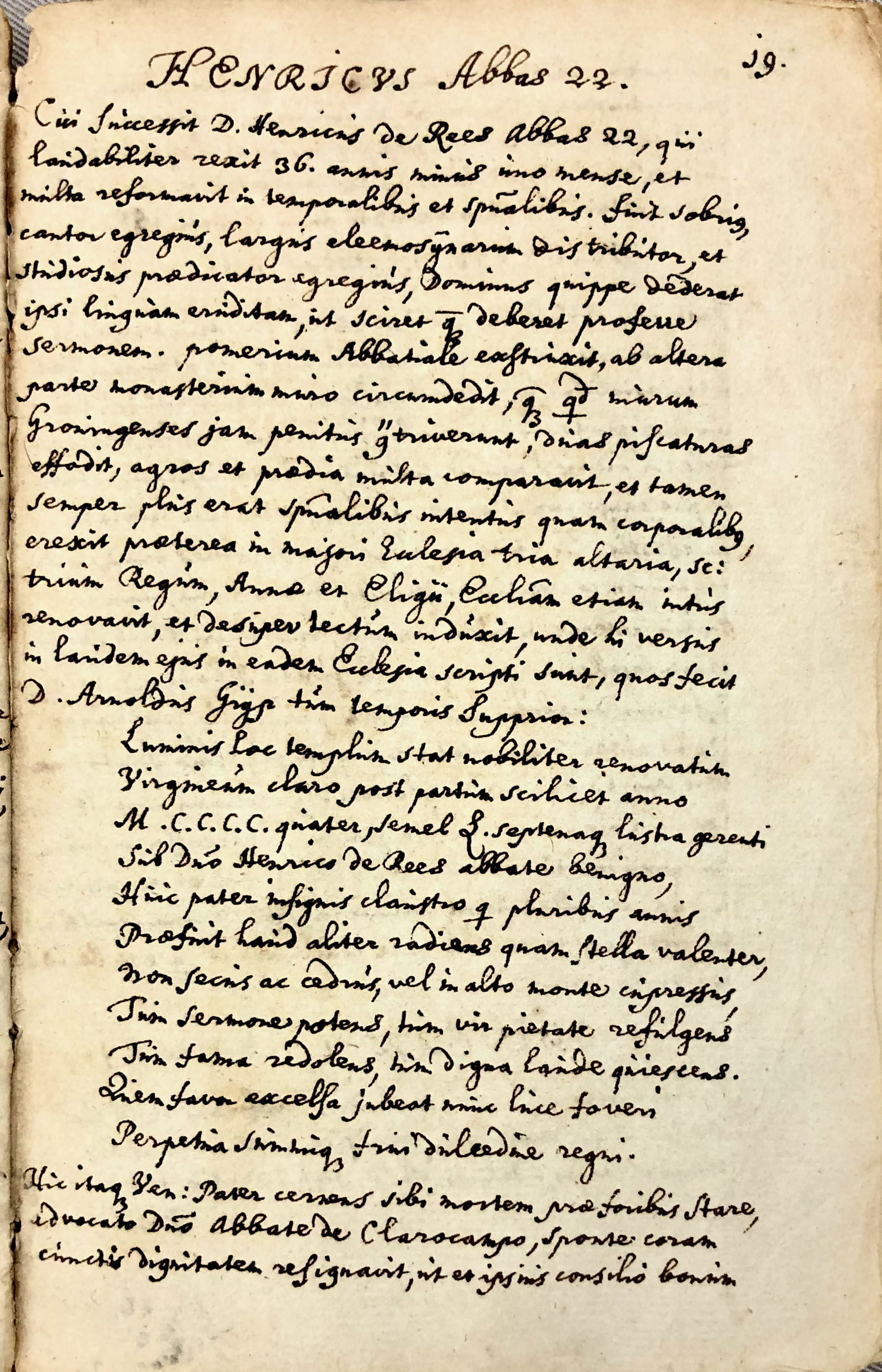

Hendrik van Rees brought about a flourishing intellectual life at Aduard.

As the abbot (1449-1485), he was the host to a group of scholars who embraced and propagated humanism, which had originated in Italy. Erasmus of Rotterdam would become the figurehead of this movement a generation later, but one of his intellectual heroes had been part of this group in Aduard: Roelof Huesman from Baflo, otherwise known as Rodolphus Agricola Phrisius. From the North and East of the Netherlands, from East Frisia and Westphalia in Germany, these men came to Aduard to inspire each other and, later, to spread humanism throughout the Low Countries. This learned culture is explicitly addressed in the text accompanying the aforementioned view of Groningen in which Aduard is visible.

Goswinus van Halen, a native of Limburg who had arrived in Groningen at an early age and who had known Agricola personally, would later write: “Anyone searching for a scholar then would have found one in Aduard ... At that time, Aduard was more an academy than it was a monastery.” Around 1528, Goswinus corresponded with Albert Hardenberg, a monk in Aduard. Albert would later convert to Protestantism and become a preacher in Emden, where his many books can now be found in the Johannes a Lasco Library. The collection also includes three books from the library of Aduard Abbey.

Aduard would ultimately meet the same fate as Yesse.

Despite (or perhaps because of) its position as mighty fortress, Aduard was an important pawn in the military battle between Catholics and Protestants—and thus between Spain and the city of Groningen on the one side, and the regions surrounding Groningen on the other—in the last years before the Reduction of Groningen (1594). As early as 1580, the abbot and the monks made a permanent retreat to the Aduard refugium at Munnekeholm in Groningen. During this period, Abbot Johannes Greven did appoint a new abbess in Yesse. In 1595, when Groningen and its surrounding regions had formally become part of the Republic of the Netherlands, and thus Protestant, the monastery was closed and, relatively soon thereafter, demolished. Some of the bricks were used to build the village of the same name. The only structure remaining in Aduard today is the former hospital ward for the lay brothers, which now serves as a Reformed church. More than twenty remnants of the monastery can be found in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. A replica of the entire hospital ward has been constructed there under the name Chapel of Aduard. Although this does not contain any authentic remains, it does illustrate the importance that was attributed to the monastery of Aduard, which extended even to 1885, when the Rijksmuseum building in Amsterdam was built.

The city of Groningen also has a monument to Aduard.

The last abbot, Wilhelm Emmen, had lived exclusively in the urban refugium. After the Reduction, he purchased a part of that refugium—the Blauwehuis [Blue House]—and bequeathed it by testament in 1604 to eight elderly ‘meagre people’ of the female sex. This would be the beginnings of the Aduardergasthuis [Aduard Guesthouse] at Munnekeholm, which is still standing, although it now serves another function.

As early as 1580, the monastery’s library went up in flames—undoubtedly a major loss, given the rich intellectual history of the monastery. It is thus no surprise that few books from Aduard have been preserved. After the Reduction, many books from the churches and mon-asteries of Groningen found their way to the library of the Martini Church. Shortly thereafter (in 1624), that library was incorporated into the University Library. Unfortunately, however, it did not contain any books from the monastery of Aduard.

Sources

- De abtenkroniek van Aduard. Studies, editie en vertaling, ed. J. van Moolenbroek & J.A. Mol (Hilversum 2010)

- Kloosters in Groningen, red. M. Hillenga & H. Kroeze (Ter Apel 2011)

- Groninger Archieven, Archive 1363 (Aduardergasthuis 1604-1984), Archival Document 13 (anno 1604)

- Jos.M.M. Hermans, Middeleeuwse handschriften uit Groningse kloosters (Groningen 1988)

- J. Loer, St. Bernardusabdij Aduard. Een reconstructie (Aduard 2001)

- J. Loer, Monnik en boer in Aduard (Aduard 2003)

- J.J. van Moolenbroek and S. Arnoldussen, ‘Twee pauselijke zegels en de vroege geschiedenis van het cisterciënzer vrouwenklooster Yesse te Haren’ in Historisch Jaarboek Groningen, 2018, pp. 6-15

- H. Muskee, De teloorgang van het klooster Aduard (Aduard 2011)

- H. Muskee, Dochters van Aduard. Familieverbanden binnen de Cisterciënzer Orde (Aduard 2014)

- Rudolf Agricola: brieven, levens en lof van Petrarca tot Erasmus, ed. F. Akkerman & A. van der Laan (Amsterdam 2016)

- C. Tromp, Groninger kloosters (Assen 1989)