The oldest Groningen resident whom we know personally was an abbot

Around 1200, a certain Emo founded a monastery on his own land. He lived in Romerswerf, a name that has now disappeared. Perhaps it refers to the town that is now known as Wierhuizen, but that was known in the 16th century as Ranswerd—which could be a bastardization of Romerswerf. There, just north of Appingedam, this Emo founded a monastery, but he was not able to find many disciples. His institution led a languishing existence. Another Emo would change that.

Emo of Huizinge took his vows in 1208.

This Emo was a cousin of Emo of Romerswerf. He was a learned young man, who had al-ready studied at Oxford. He is still remembered at Oxford as the first student from the European mainland. Together with his cousin, he decided to affiliate the dual monastery (for men and women) with one of the monastic orders existing at that time, so that it would enjoy the ecclesiastical protection of the Mother house, and therefore of the Church and the Pope. Ecclesiastical protection meant societal protection, as the Church was omnipresent and more powerful than any secular ruler. Emo chose the order of the Premonstratensians. The name is derived from Prémontré in Northern France, where Norbert of Xanten had founded the first monastery of this order. The monks were also named Norbertines, after their founder. From that time on, Emo and his monks would wear the white habit that is characteristic of the Premonstratensians.

Emo also wanted to have a church for the monastery.

Affiliating with the order also meant a compulsory organization in accordance with the Mother house. A monastery church played a central role in this organization. He would find his church about thirteen kilometres to the southwest, in Wierum. The church wardens there held a vote, and the majority agreed to grant the church to the monastery. One local nobleman, however, did not agree. He contested the decision to the Bishop of Münster, who presided over this region. The bishop ruled in his favour, but Emo decided to appeal to the Pope.

Emo went to Rome to obtain his church and justice.

This was remarkable, not only because of the distance (about 2,000 km), but primarily because his journey meant that there was an assumed justice that was recognized and obeyed everywhere. His journey would have been pointless without an international body that had the authority to determine, impose and enforce what was to be the law in situations like this. Today, we do not have such a body whose authority is recognized everywhere and in all areas of human life. In Emo’s time, however, it was the Catholic Church, on the grounds of ecclesiastical authority and the canon law that Emo had studied in Oxford and elsewhere. The Pope recognized Emo’s right and, after his return to Groningen, the case was settled in his favour.

Emo subsequently relocated the monastery to Wierum.

There, it would remain for some 350 years, until its dissolution in 1561. The monastery was the town, and the town thus came to be called Wittewierum (Whitewierum), after the habit of the monks. All of them were men, as the women remained behind in Romerswerf, where the location lived on as a convent under the name of Rozenkamp (Campus rosarum). From that time on, Emo called the monastery in Wittewierum ‘Bloemhof’ (Hortus floridus).

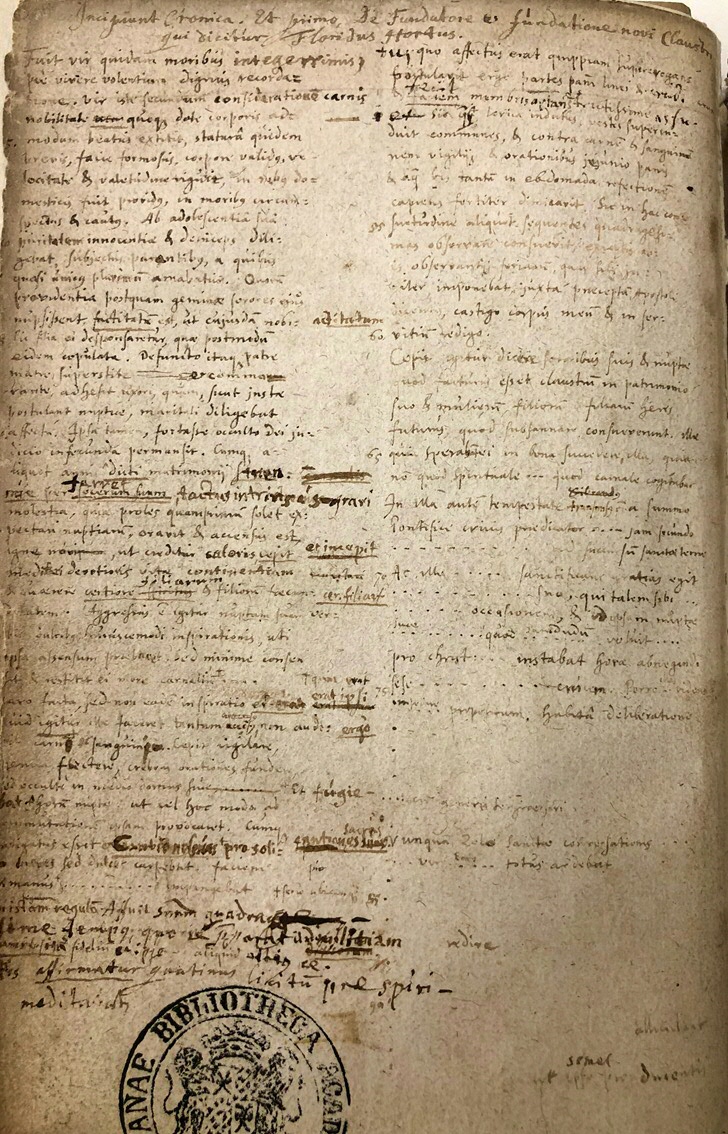

He wrote down the history of the monastery.

Emo did this in the form of annals. Each year, he noted eventsinside and outside the monastery, always in the third person as an omniscient narrator, even when writing about himself. After Emo’s death, his second successor Menko continued the tradition. In this way, a history of this monastery covering the first century of its existence was preserved. This chronicle tells us virtually all that we know about the monastery, including everything stated above.

Only one original version of this chronicle of Bloemhof is still in existence.

It is a version that was written on parchment entirely by Menko himself. First, he copied Emo's text and then he added his own text for many years. Until 1561, this manuscript was part of the abbey's library at Wittewierum. The last abbot took it with him when he left. Since 1852, it has been in the possession of the University of Groningen Library (HS 116). Before that, it had been the property of a variety of private parties. Around 1600, it was in the hands of Ubbo Emmius, who used it as an historical source for his Rerum Frisicarum historia (History of Frisia, 1616). Ubbo made many annotations in the manuscript, which consists of around 100 pages in all, each with two columns of text.

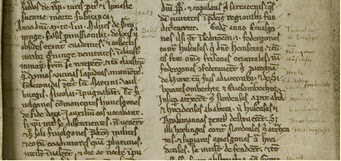

A sort of copy of this version has also been preserved.

We owe this to an anonymous person who wrote an extract of Menko’s version around 1600. This scribe was apparently working in a Frisian environment, as he copied only events that were relevant to Friesland, and in a relatively sloppy manner. Since 1819, this version has also been in the possession of the University of Groningen Library (HS 117). It would not have been of much historical value, had it not also contained a continuation of the history of the monastery after the death of Menko—covering the last quarter of the 13th century.

The chronicle contains facts, opinions and disclosures.

Remarkably, it tells us rather little about events within the monastery. The narratives primarily concern what had occurred outside of the monastery, both nearby and far away, but that had (or could have had) consequences for the monastery. It further tells how Emo and, later, Menko evaluated such events. One extraordinary category consists of the personal musings (soliloquia) of Emo. They clearly show that he could not only be enterprising and self-assured, but that he also harboured deep uncertainties throughout his entire life, particularly as the leader of the monastery. For example, he often assigned blame to himself for floods and other disasters, which obviously occurred on a regular basis. He continually wonders whether God was trying to punish him for his deeds.

Emo looked at the world through the eyes of a monk.

He notes (col. 53) that Frisia—what is currently Groningen, Friesland and East Frisia—had many convents and monasteries, as well as many inhabitants, enjoyed freedom (“a matter of incalculable worth”), was prosperous and had a wealth of livestock, grazing lands and crops. It was perhaps for this reason, Emo muses, that floods, famine and plagues occurred, as God wished to use them to exact gratitude from Frisia for all of the blessings He had given to the area. Those who truly wish to be saved will have to retreat from other people (col. 40) and enter a monastery. That is the source of eternal life. It is there that one can cast off the burden of worldly possessions and receive in exchange the blessings of the spiritual life. It is there that one can learn how to give and receive patience, thereby becoming immune to the temptations of the world (col. 55 and 66).

He devotes a great deal of attention to the intractable reality.

Emo and Menko mention more than a few non-Christian events—close to home, such as the conflict with Abbot Herderik of Schildwolde which began in 1223 (col. 70 ff.) and the suffering of the hermit of Stitswerd (col. 99), and far away, as with the extensive report of the long nautical journey made by a contingent of Frisian crusaders in 1217 (col. 25 ff.) and the murder of the Archbishop of Cologne (col. 88 ff.). Taken together, a colourful procession of topics passes in review.

![In the entries for the year 1222, Emo writes: “When the moon was 14 days old, on the day after the Feast of the 11,000 Virgins [22 October], there was a lunar eclipse. In August, for many nights, many people saw an unknown flame-throwing star in the North.” Alongside this entry, in the margin, Ubbo Emmius wrote: cometa. UBG HS 116, fol. 16r, col. 62](/library/_shared/images/bc/virtual-exhibitions/yesse/yesse-54.jpeg)

The chronicle of Bloemhof thus reflects life in the 13th century.

In the entries for the year 1226, it is poignant to note the almost casual mention of the death of Francis of Assisi. Suddenly, you realize that Emo was one of his contemporaries. All of a sudden, you become aware of how extraordinary it is that we are able to cherish this personal report from the 13th century as a possession forever.

Sources

- H.P.H. Jansen & A. Janse, Kroniek van het klooster Bloemhof te Wittewierum. Inleiding, editie en vertaling (Hilversum 1991)

- D.E.H. de Boer, Emo’s reis. Een historisch culturele ontdekkingstocht door Europa in 1212 (Leeuwarden 2011)

- P.H. Donner, Zou Emo nu nog gaan—en waarheen? Vierde Abt Emo Lezing (Wittewierum 2018)