Capturing the act of reading and writing

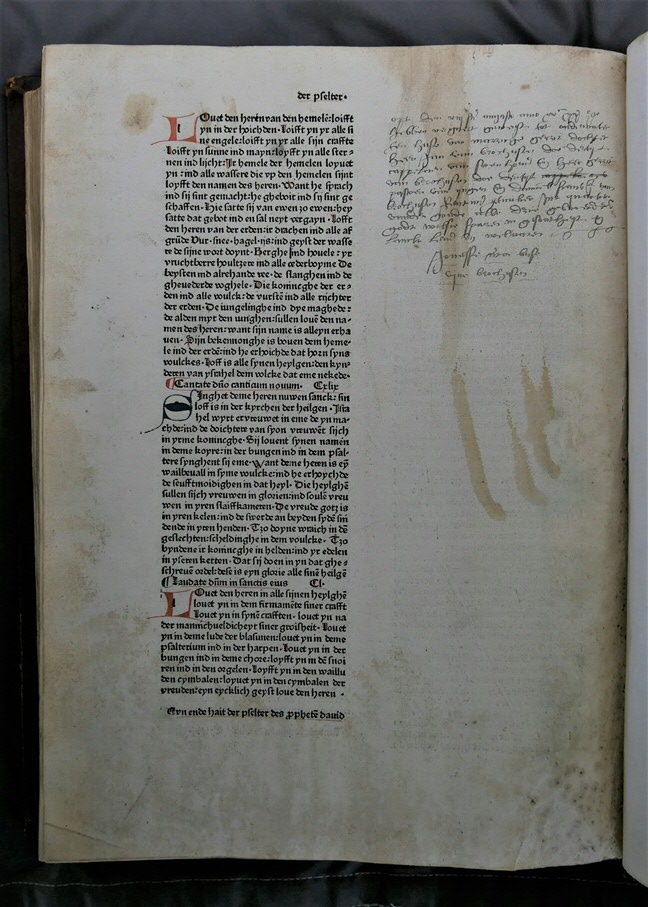

Even after a book had been printed, sold and illuminated, its appearance was not fixed. During its centuries of use, users continued to make all kinds of additions and alterations. While reading, they could change the book’s material make-up and visual appearance by inserting leaves, noting comments in the margins or crossing out passages. These elements captured as it were the fleeting act of reading and reveal much about readership and reading practices, specifically how users interacted with both the textual content and the physical features of the book.

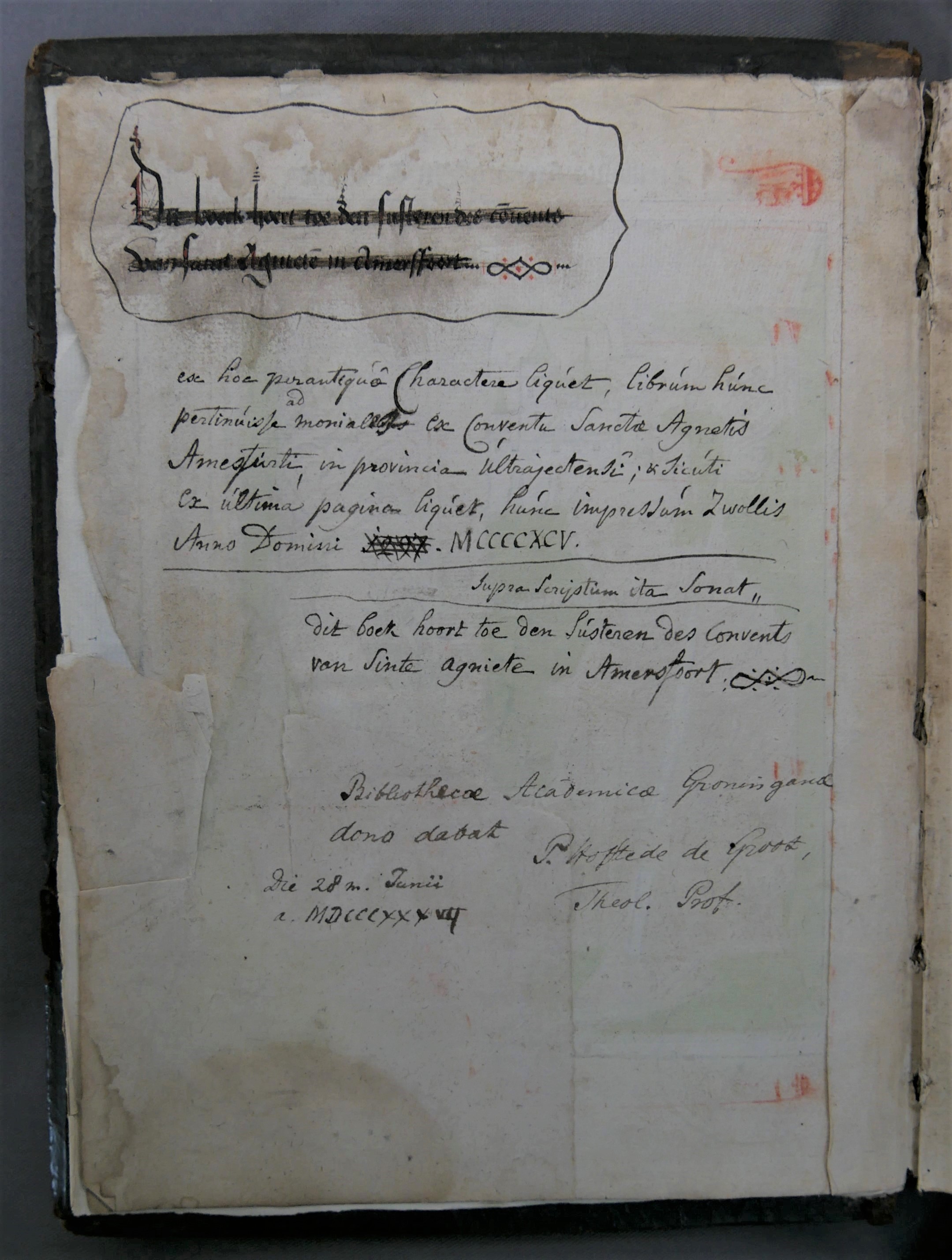

Reading in the convent of Saint Agnes in Amersfoort

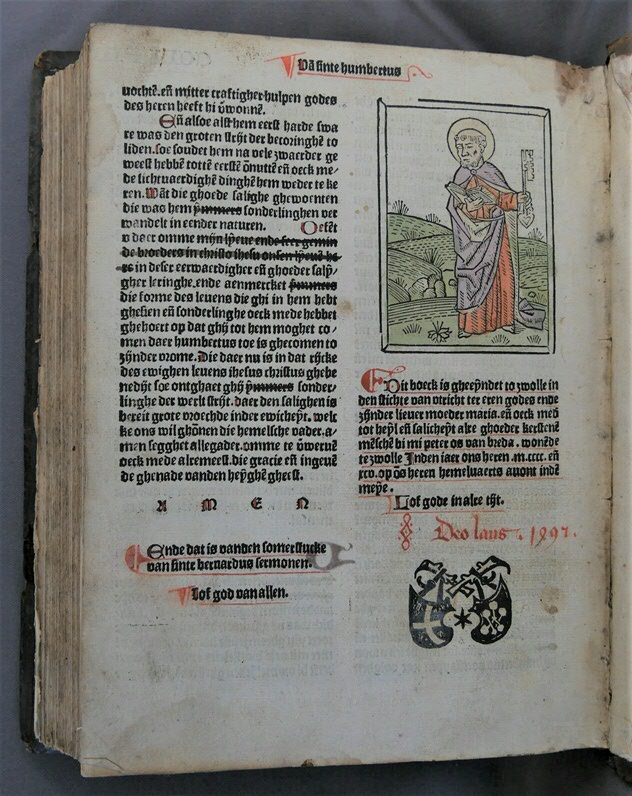

A copy of a Middle Dutch edition of Bernard of Clairvaux’s sermons, printed by Peter van Os in Zwolle in 1495, belonged to a community of tertiaries of Saint Agnes in Amersfoort. A crossed-out inscription on the first folio can still be made out. It reads: ‘Dit boec hoert toe den susteren des convents van Sanct Agneten in Amersfoort’. On the last folio, a rubricator’s note has been added in the same hand as the inscription, stating the common phrase ‘Deo laus’ (praise to God) and the year 1495, suggesting that the book was acquired by the tertiaries in the year that it was printed.

The text itself has been systematically altered by crossing out and adding elements, and by correcting textual errors. For example, the sermons’ text frequently addresses the intended reader as ‘mijn lieve broeders’ (my dear brothers) or using similar phrasing. These vocative forms have all been crossed out, which may be explained by the fact that the book belonged to a community of women. Moreover, all Latin passages have been crossed out, as well as all instances of ‘ymmer’ and ‘ymmers’ (which sometimes occur three times on one page). Signs have been added in the margins to structure the text, such as numbers indicating key passages. While these alterations could indicate that some (or all) of the community had little knowledge of Latin, they might also have been a way to facilitate reading the text aloud, allowing the reader to easily omit the more complex or redundant phrases.

A rare source on these tertiaries survives, written by their confessor Jan de Wael in 1510 and entitled ‘Informieringheboeck der jongen’ (Manual for the Young Ones). [1] This manuscript reveals that reading both privately and publicly formed a vital component of the women’s education and that they mainly read Middle Dutch (as opposed to Latin) texts. A palaeographic comparison between Jan de Wael’s manuscript and Bernard of Clairvaux’s sermons has shown that the alterations to the printed text were made by Jan de Wael himself. [2]

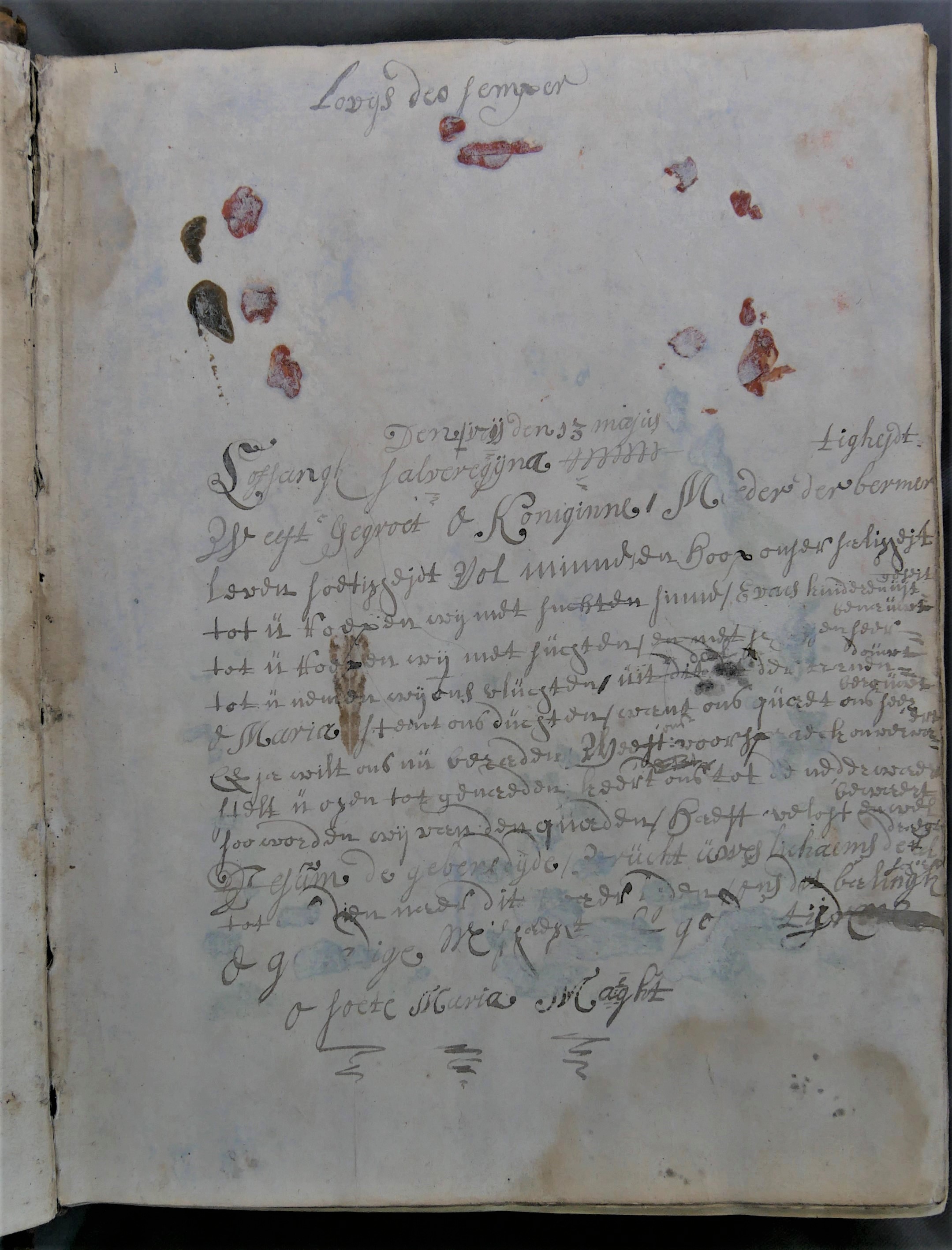

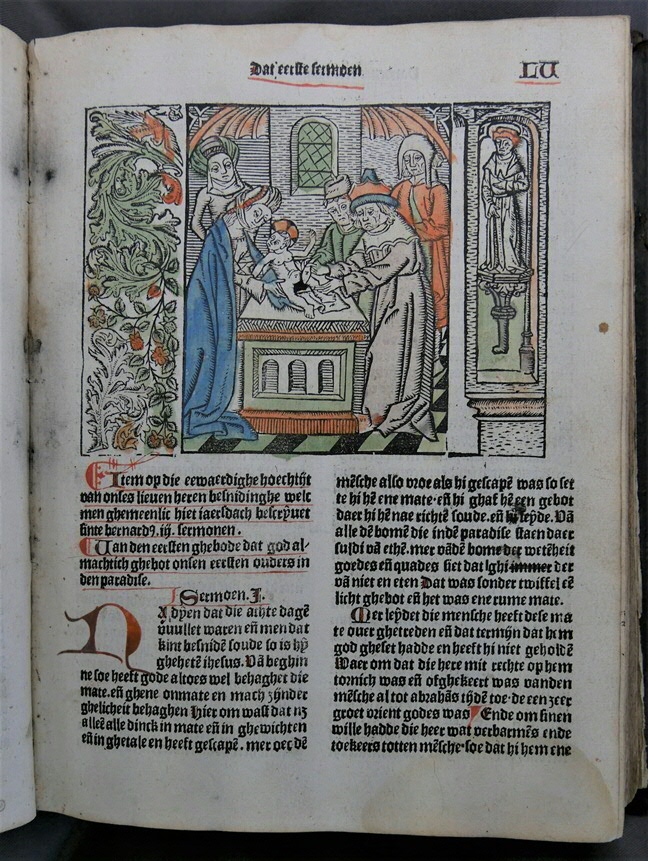

Other additions include a handwritten Marian hymn ‘Lofsangt salveregijna’. Traces of wax on the paper suggest that a piece of paper, possibly with an image, had been pasted into the book. Further on in the book, in a woodcut depicting the circumcision of Christ, the child’s genitals have been covered neatly by a blob of ink. These traces reveal how users could interact with a book in a wide variety of ways, correcting, structuring, commenting and censoring. The book and its text were far from fixed, but continued to be shaped in accordance with wishes and needs.

Books as mementos

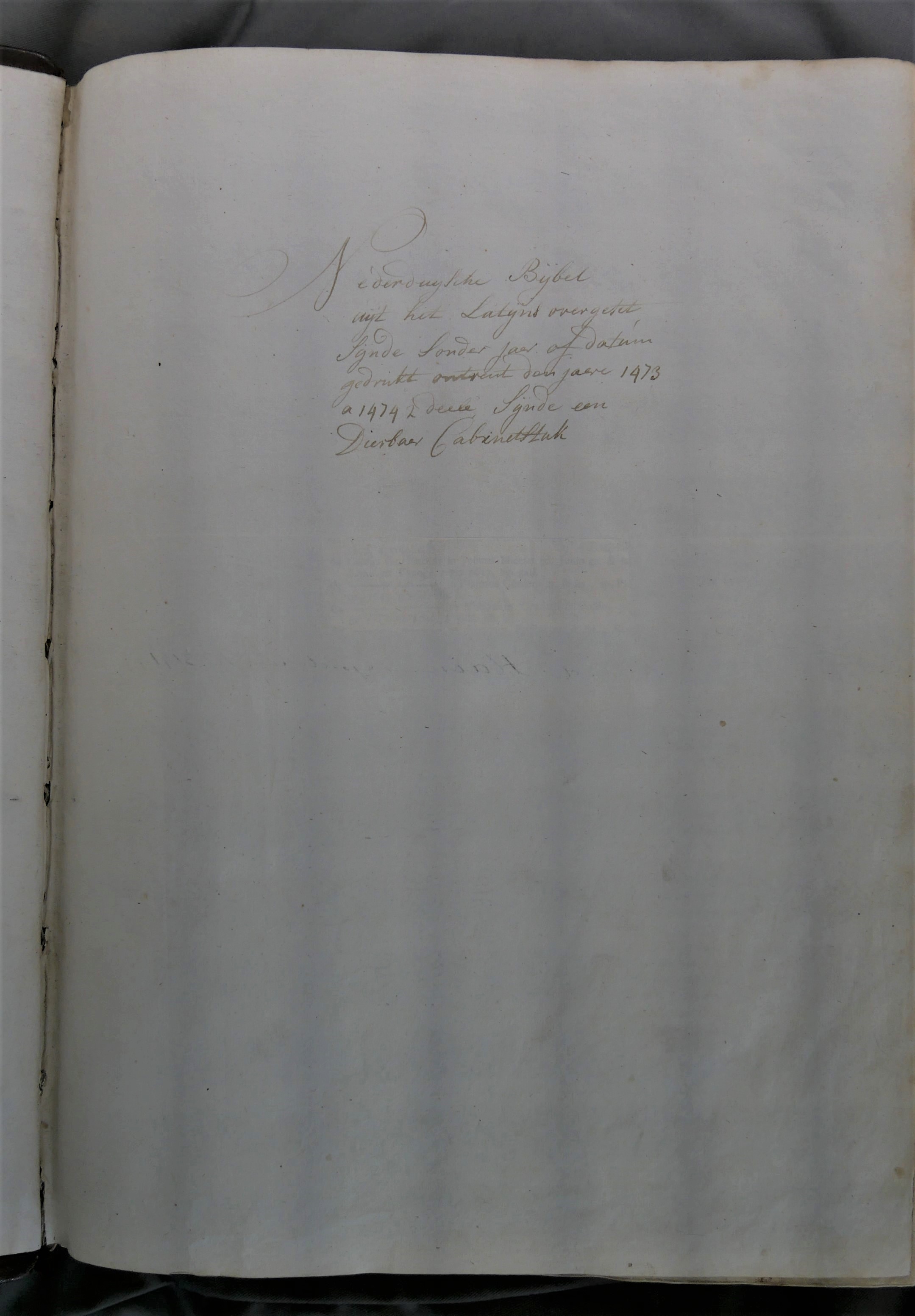

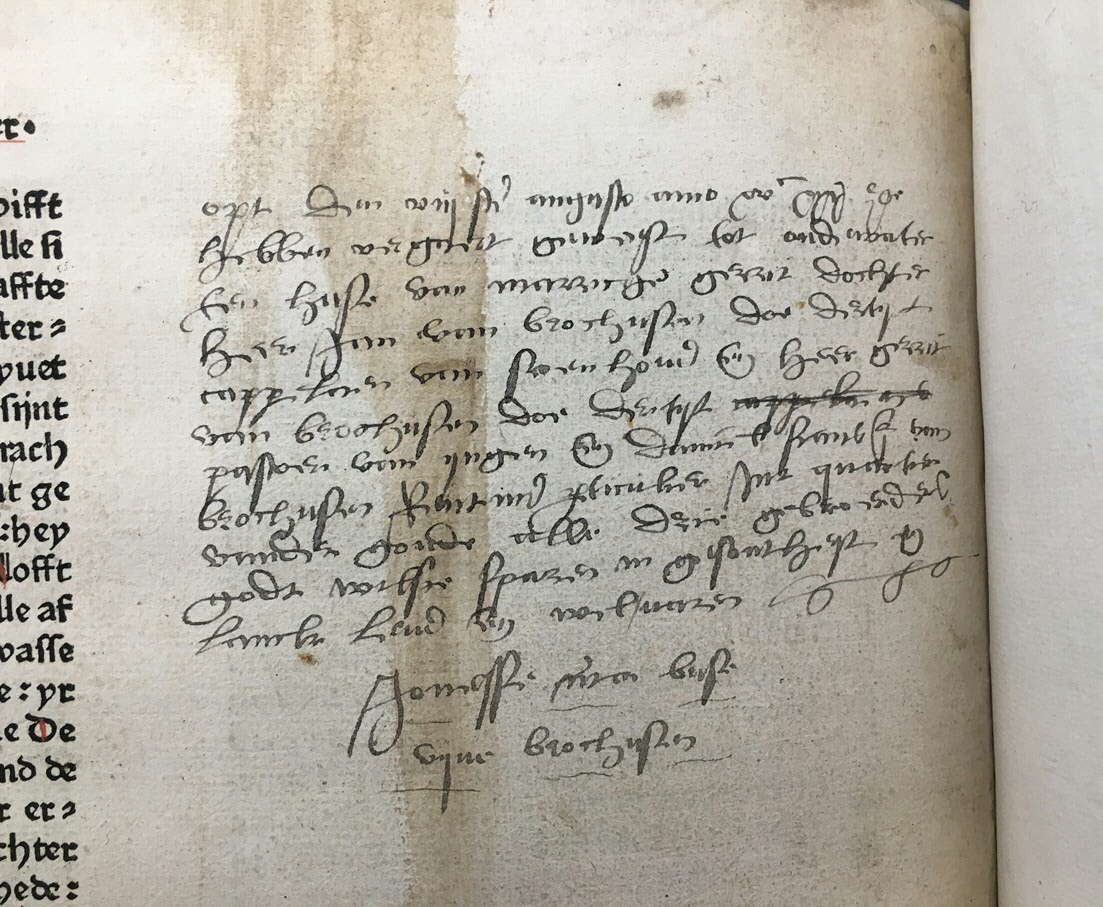

Although books function as objects of textual transmission, they can be highly meaningful in a variety of other ways. A Bible bound in two volumes and printed by Bartholomaeus de Unkel and Heinrich Quentell in Cologne in 1478 or 1479 contains a personal inscription at the end of the first volume:

Opt den VIIIsten augusto anno XVc XXXI hebben vergaert gewest tot Oudewater ten huse van Marritjen Gerrit dochter, heer Jan van Brochusen doe dertijt cappelaen van Scoenhoven ende heer Gerrit van Brochusen doe dertijt pastoer van Yngen ende Daniel Fransz. van Brochusen Rentmeester particulier int quartier vander Goude, alle drie gebroeders. Godt wilse sparen in gesondheyt ende lanck leven ende welvaren.

The inscription records an apparently special event, whereby on 8 August 1531 the three brothers Jan, Gerrit and Daniel Fransz. van Brochusen had gathered at the house of Marritjen Gerrit dochter, to whom they were probably in some way related. The inscription expresses a wish for God to keep them in good health, a long life and wellbeing. Books, with their parchment or paper folios, were ideal objects for documenting such memorable events. Family Bibles in particular, which were passed down from generation to generation, functioned as especially apt sites of commemoration. Clearly, this Bible passed into the hands of another owner who cherished it, as they noted in an inscription that the book was a ‘Dierbaer Cabinetstuk’ (precious cabinet piece).