Studentbijdragen

Ten geleide: hoe de bijdragen te lezen?

De bijdragen over geselecteerde regio’s uit de Grooten Atlas kunt u beschouwen als eerste verkenningen. De studenten hebben onderzoek gedaan naar de wijze waarop de oorspronkelijke bevolkingen worden beschreven en ze geven daarvoor mogelijke verklaringen. Ook gaan ze in op de bronnen waar Blaeu zich op heeft gebaseerd. Vooral de actualiteit (of het gebrek daaraan) wordt hierbij aangestipt. Zoals hiervoor al aangegeven gaf Blaeu in veel gevallen verouderde informatie door. Tot slot wordt in elke bijdrage een leessuggestie gedaan voor verdieping. Dat kan specifiek gaan over verdieping in de behandelde regio. Maar ook kan gewezen worden op een groter, overkoepelend thema, zoals de wijze waarop buiten-Europese bevolkingen in vroegmoderne literatuur stelselmatig gemarginaliseerd zijn. Iedere bijdrage opent met een nummer, de titel van de kaart, en de titel van de tekstbijdrage zoals die in de Grooten Atlas is weergegeven. Het nummer verwijst naar het voor historisch cartografen onontbeerlijke referentiewerk Atlantes Neerlandici van C. Koeman (9 delen). Het tweede deel in de serie behandelt de atlassen in folio-formaat die Willem Jansz Blaeu en Joan Blaeu uitgaven. Met het “Koeman nummer” kunnen geïnteresseerden in de historische cartografie razendsnel de juiste kaart terugvinden. Datzelfde geldt tot op zekere hoogte voor de titel van de kaart. Tot op zekere hoogte, want kaarttitels werden vaak overgenomen door concurrerende kaartenuitgevers en zijn als zodanig dus niet uniek voor het kaartmateriaal dat in de Grooten Atlas is opgenomen. Met de titel van de tekstbijdrage kunt u snel de juiste passage in de delen van de Grooten Atlas achterhalen. We onthouden ons hier van pagina- (of folio)verwijzing, omdat de collatie van de atlas (licht) kan verschillen.

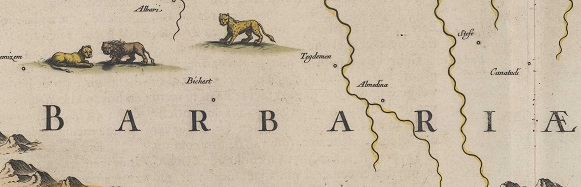

Noord-Afrika, door Jesper Bergsma

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: BARBARIA / Barbarien

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, vol. II, nr. 8610:2

Barbarije is de regio die wij nu kennen als Noord-Afrika. Het omvat in de atlas van Blaeu de koninkrijken Marokko, Fez, Algiers, Tunes en Tripoli. Dat is het huidige Marokko, Algerije, Tunesië en Libië. De regio kent een lange en turbulente geschiedenis als het gaat om de relatie met Europa. Zo vormde de regio het thuisland van generaal Hannibal (247-183/2), die de Romeinen uitdaagde tijdens de Tweede Punische Oorlog. In de tijd van Blaeu waren het de Barbarijse zeerovers die de Europese gemoederen bezighielden.

Veel van deze aanvallen waren erop gericht de bemanning gevangen te nemen en tot slaaf te maken of dienden om losgeld te eisen. Omdat het aanvankelijk vooral katholieke zeevaarders betrof, deerde het de Nederlandse Republiek weinig. Dit veranderde toen ook koopvaarders uit de Republiek werden aangevallen en tot slaaf gemaakt. Saillant detail is dat niet alleen Nederlanders tot slaaf werden gemaakt, maar dat er ook sprake was van zogenaamde ‘renegaten’: Europeanen die zich aansloten bij de Barbarijse zeerovers en moslim werden. Zij droegen op deze manier belangrijke maritieme kennis over.

Deze geschiedenis zou invloed gehad kunnen hebben op de tekstbeschrijvingen in de Grooten Atlas over Barbarije. Blaeu laat zich in de tekst regelmatig negatief uit over de volkeren die hier leven. Hij noemt ze ‘grootspreckers’, ‘wantrouwigh’ en ‘lichtgeloovigh in onzekere dingen’. Vanwaar dit grotendeels negatieve sentiment ten aanzien van de volkeren in deze regio? Zou dit voortkomen uit het gedrag van de zeerovers, dat toch verre van beschaafd genoemd kan worden? Of ging het om een Europees gevoel van (religieuze) superioriteit, als we bedenken dat het een grotendeels islamitische regio betrof?

Een plausibele verklaring kan liggen in het verschil van geloof. De islam werd nu eenmaal als een ‘valse profetie’ gezien door christelijke auteurs, op wie ook Blaeu zich baseert. Maar kan er wellicht enige sprake zijn van eigen maatschappijkritiek bij Blaeu? In een calvinistische omgeving veroorloofde de uitgever zich erg veel religieuze vrijheid en gaf hij ook katholiek drukwerk uit. Hierin schuilt een interessant onderzoeksvraagstuk.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Brood, P. (red.) 2018. De wijde wereld van Cornelis Pijnacker (1590-1645) . Zwolle: WBOOKS.

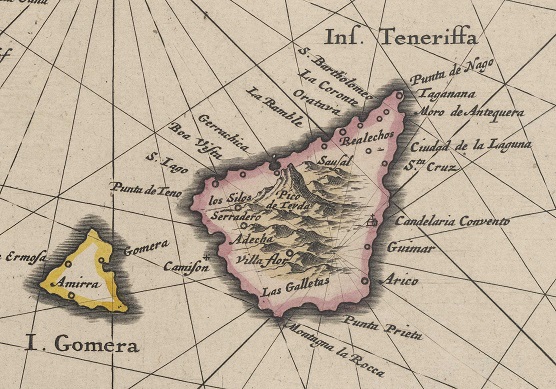

Canarische eilanden, door Suze van Dijken

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: INSVLÆ CANARIÆ / De Canarische Eylanden

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, vol. II, nr. 8970:2

Tot de Canarische eilanden worden in de tijd van Joan Blaeu de eilanden Palma, Hierro, La Gomera, Tenerife, Gran Canaria, Fuerteventura en Lanzarote gerekend. Blaeu vindt de kleinere eilanden weinig belang hebben en benoemt ze verder niet. Informatie achterwege laten lijkt een trend te zijn in de tekst die Blaeu opnam over de Canarische eilanden, waarbij het de vraag is of dit een bewuste keuze was of niet.

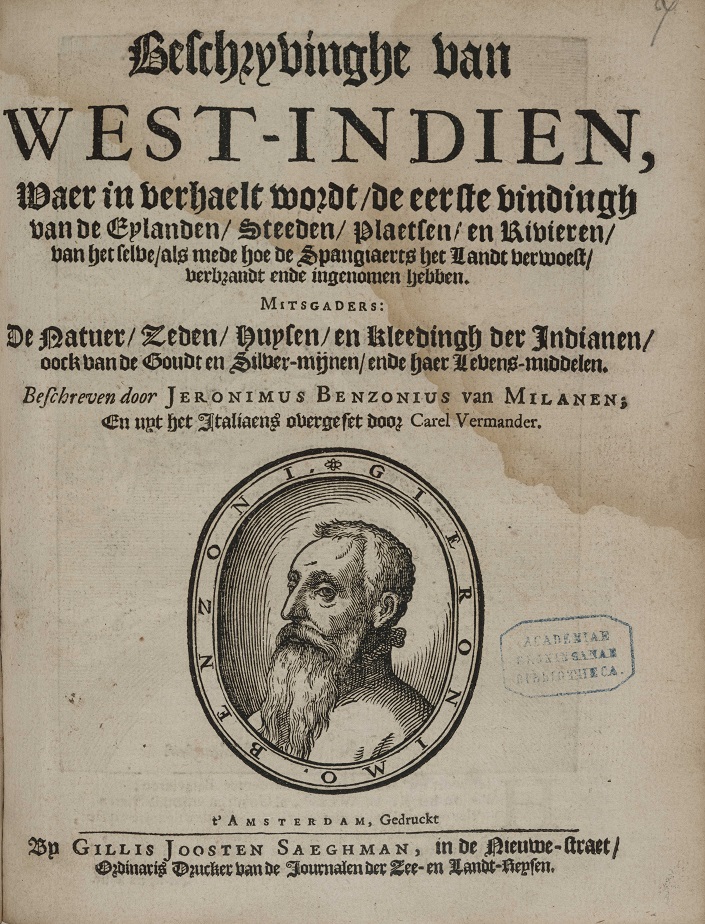

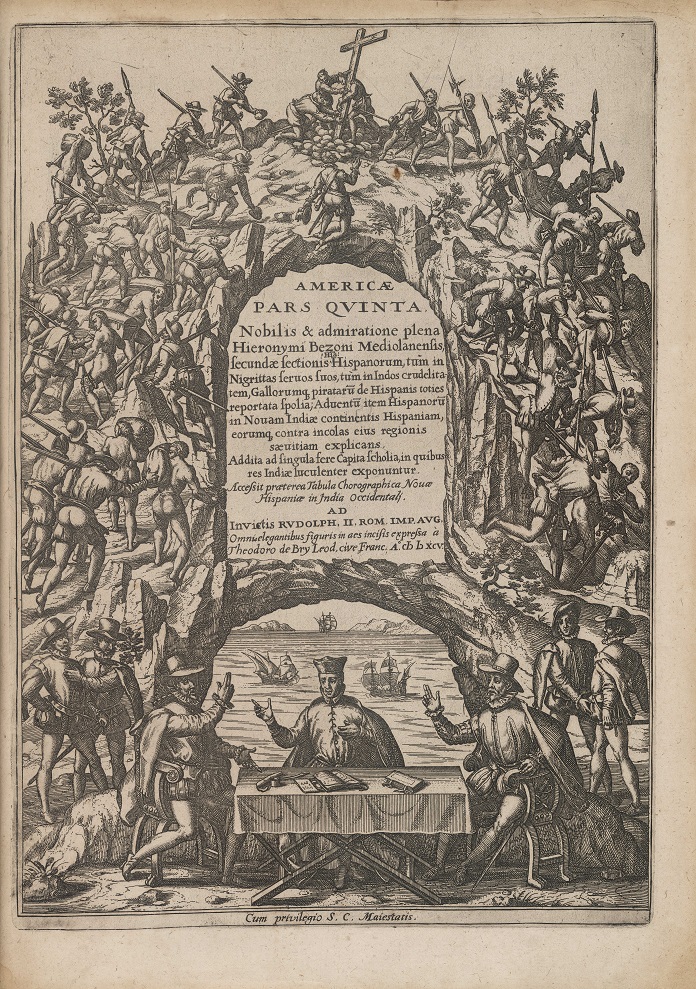

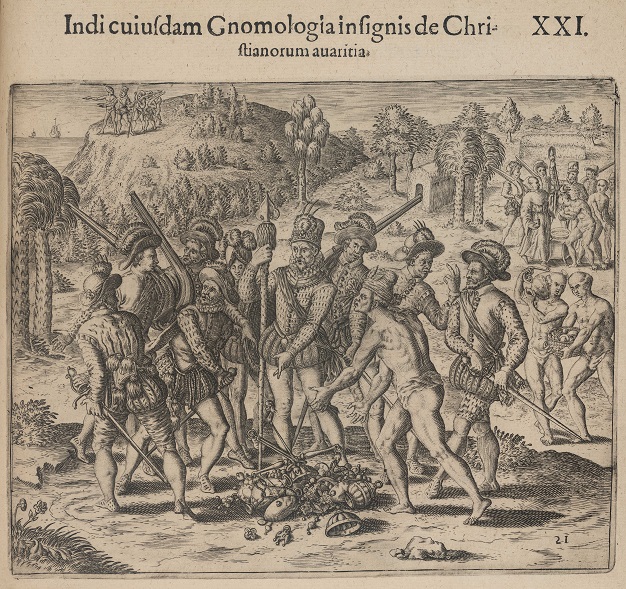

Zo vermijdt Blaeu de bespreking van de verovering van de Canarische eilanden door Spanje. Hij heeft het maar één keer in de tekst over een strijd die tussen de Spanjaarden en de oorspronkelijke bevolking zou hebben plaatsgevonden. Hier noemt hij ze “barbaren” en gaat niet in op hoe de strijd om de eilanden nu exact verliep. Waarom refereert Blaeu niet aan deze evenementen, terwijl hij wel de beschikking had kunnen hebben over deze informatie? Tussen 1565 en 1727 verschenen er namelijk maar liefst 11 edities van Historia del Mondo Nuovo van Girolamo Benzoni (circa 1519-1572). Deze Italiaanse avonturier heeft in zijn boek veel aandacht voor de wreedheid die hij in Amerika aantrof en is vooral kritisch op de Spaanse hebzucht en mishandeling van de oorspronkelijke bewoners. In Benzoni’s hoofdstuk over de Canarische eilanden beschrijft hij een aantal van de gewelddadige botsingen tussen de Spanjaarden en de bevolking. Over de slag bij het eiland La Gomera: ‘Landing a hundred and twenty men there, they (the Spanish) were attacked with such courage and ferocity by the natives, that the greater part of them were killed.’

De lange periode van verovering, nederlaag en uiteindelijke kolonisatie door de Spanjaarden wordt door Blaeu slechts summier beschreven. Opvallend is dat Blaeu een link legt tussen de geleidelijke bekering tot het christendom en de aard van de oorspronkelijke bewoners, die hierna verzachtte. De “barbaren” waren oorspronkelijk namelijk ‘oorlogszuchtig’. In deze beschrijving schuilt impliciet Europees superioriteitsdenken. Er wordt geïmpliceerd dat door het aannemen van het christelijke geloof ze een trede op de beschavingsladder stegen. Maar of dat proces nu wel zo vredig verliep als Blaeu suggereert…?

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Benzoni, G. and W. Smyth (ed.) (2010). History of the New World, by Girolamo Benzoni of Milan: Shewing His Travels in America, From A.D. 1541 to 1556 . Surrey: Ashgate.

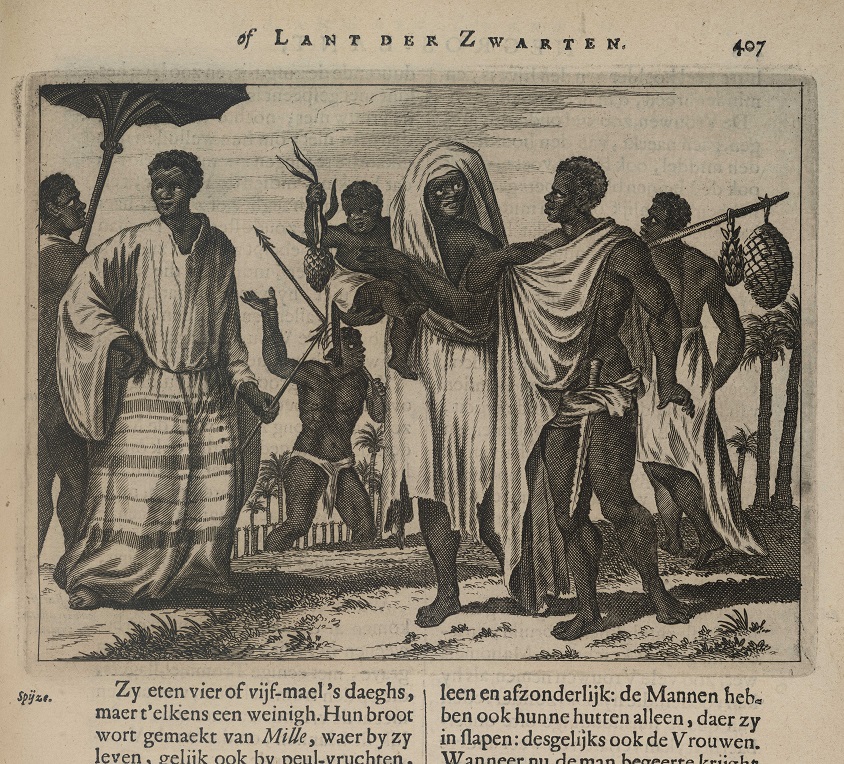

West-Afrika, door Famke Visser

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: NIGRITARVM REGIO / ’t Landt der Mooren Oft Swarten

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 8750:2

’t Landt der Swarten oft Mooren, oftewel de regio West-Afrika, kende in de zeventiende eeuw veel interactie met Europese zeevarende naties. Het waren aanvankelijk de Portugezen die vanaf de vijftiende eeuw de kusten verkenden. Op de kaart van Blaeu is dit duidelijk terug te zien in de plaatsnamen. Vanaf begin zeventiende eeuw vestigen ook de Nederlanders zich te West-Afrika en neemt het gebied een belangrijke positie in binnen de zogenaamde Trans-Atlantische handelsdriehoek.

In de beschrijving van West-Afrika geeft Blaeu veel ruimte aan de natuurlijke historie. Enkele pagina’s zijn gewijd aan landschapsbeschrijvingen en de rivieren in het gebied. Een belangrijk thema dat tijdgenoten van Blaeu bezighield was waar de Nijl precies zijn oorsprong had. Omdat de wijze waarop de rivier de Niger buiten de oevers treedt overeenkomt met de wijze waarop de Nijl buiten de oevers treedt, suggereerden sommige auteurs dat er een connectie tussen beide rivieren moest bestaan. Blaeu neemt deze discussie over in zijn regiobeschrijving.

De naamgeving van de regio mag opmerkelijk klinken, maar is simpel te verklaren: het is een verwijzing naar de huidskleur van de inwoners van West-Afrika. Hoewel de naam van het gebied dus hiernaar verwijst, valt het op dat er in de Grooten Atlas verder maar enkele keren wordt gesproken over het feit dat de huidskleur van de bevolking ‘peckswart’ is.

Een ander thema waar relatief veel aandacht voor is in Blaeu’s beschrijving van West-Afrika betreft religie, of het vermeende gebrek hieraan. Zo worden de inwoners van het land Nubië (een gebied dat overlapt met het huidige Egypte en Soedan) beschreven als christenen, maar wordt hierbij benadrukt dat deze vorm van christendom compleet verschilt van de protestantse richting. Een belangrijke bron voor Blaeu voor West-Afrika vormde het werk Della descrittione dell’ Africa et delle cose notabili che ivi sono (1556) (= De beschrijving van Afrika en de noemenswaardige dingen die daar zijn) van reiziger en schrijver Leo Africanus (ca. 1494-1554). We zien in passages dat Blaeu bijna letterlijk de tekst van Africanus kopieert. Eén van deze passages is bijvoorbeeld een beschrijving van Borno, waar volgens Blaeu de inwoners ‘leven als d’onvernuftige dieren’ door hun gebrek aan religie, een beschrijving die Africanus ook al gaf.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Cannon, K.G. (2008). “Christian Imperialism and the Transatlantic Slave Trade,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 24 (1), pp. 127–134.

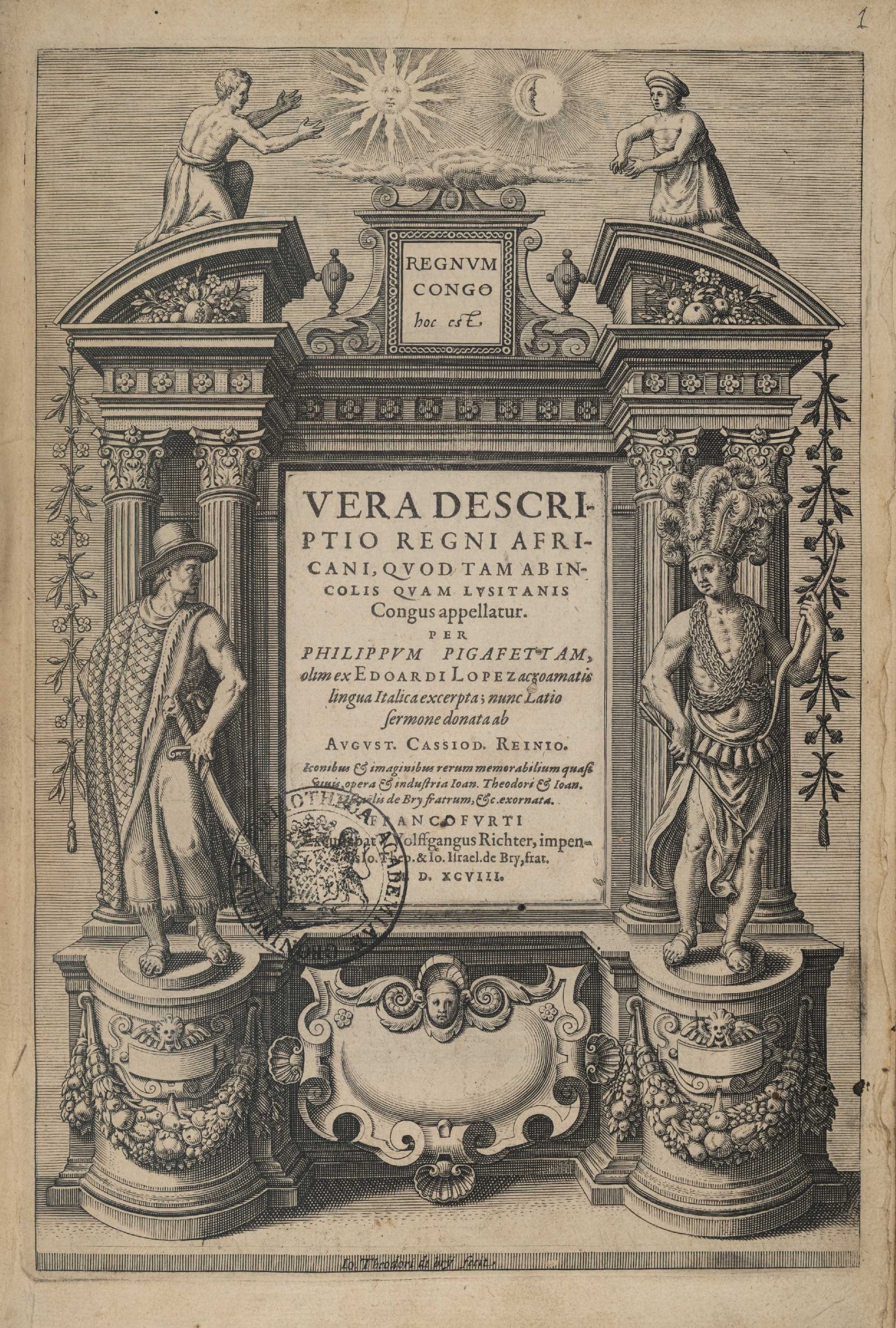

Congo, door Koen Nijensteen

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: REGNA CONGO ET ANGOLA / ’t Koninckryck Congo

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 8755:2

Een hardnekkig stereotype is dat hernieuwde interesse in, en toegang tot, de oude Griekse en Latijnse teksten Europa vanaf de vijftiende eeuw uit de Middeleeuwen trok. Daarmee wordt voorbijgegaan aan eeuwenoude en continue contacten tussen Europa en de islamitische wereld, die veelal via het Byzantijnse rijk liepen. Het is wel waar dat met de boekdrukkunst meer “verloren gewaande” bronnen uit de Oudheid toegankelijker werden gemaakt. Deze overdracht van kennis betekende tegelijkertijd een overdracht van vooroordelen.

Zo stelde Katherine George dat de categorisering van Aristoteles — ‘is het niet Grieks, dan is het onbeschaafd’ — de basis vormde van de manier waarop menselijke verschillen werden geobserveerd in de zestiende eeuw. Met het oog op het groeiende aantal reisverslagen in deze periode, een fascinerende stelling. Het was de Amsterdamse drukker en uitgever Joan Blaeu die veel informatie uit deze reisverhalen samenvatte en tezamen met zijn kaarten publiceerde in het twaalfdelige luxeproduct dat in de jaren 1660 door hem werd uitgegeven: de Atlas Maior.

Eén van de bronnen die Blaeu gebruikte voor zijn beschrijving van het Afrikaanse Koninckryck Congo heeft tot aan de negentiende-eeuwse “scramble for Africa” de basis gevormd voor de kennis over dit gebied, met alle gevolgen van dien. Blaeu maakte voor zijn beschrijving van Congo gebruik van het derde deel van Jan Huyghen van Linschoten’s Itinerarium dat in 1596 werd uitgegeven. De reiziger Linschoten was zelf nooit in Congo geweest en baseerde zijn beschrijving dan ook op het reisverslag van een Portugese koopman: Duarte Lopes. De Portugees wist — binnen slechts enkele jaren! — het vertrouwen van de Congolese koning te winnen, en werd door hem in 1584 naar de paus gestuurd met het verzoek om katholieke missionarissen te sturen.

De beschrijvingen van Lopes waren uitzonderlijk positief, en duidelijk van een man die affiniteit met het gebied en de mensen had. Lopes was naar alle waarschijnlijkheid een slavenhandelaar. Het reisverslag werd een “bestseller” en binnen enkele jaren verschenen vijf vertalingen. Een eeuw later rechtvaardigde de in versnelling toenemende transatlantische slavenhandel al een hernieuwde Nederlandse vertaling. Maar des te opmerkelijker is het dat er in 1881 en 1883 nieuwe Franse en Engelse vertalingen verschenen, precies op het scharnierpunt van de ‘scramble for Africa’.

De Amerikaan Richard Cole stelde, op basis van onderzoek naar zestiende-eeuwse reisverslagen, dat de eerste indrukken die gemaakt werden door Europese ontdekkingsreizigers, een permanent onderdeel gingen vormen van het ethos van de Westerse cultuur. Het is in dat licht bezien wel schrijnend dat de bijzonder positieve beschrijving van Duarte Lopes in schril contrast staat met het leed dat Congo onderging tijdens de koloniale periode.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Cole, R.G. (1972). “Sixteenth-Century Travel Books as a Source of European Attitudes toward Non-White and Non-Western Culture,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 116 (1), pp. 59–67.

Madagaskar, door Bas van der Heide

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: ÆTHIOPIA SVPERIOR VEL INTERIOR / Het Koningkryck Abissinen

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 8720:2

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: ÆTHIOPIA INFERIOR, VEL EXTERIOR / Neder-Æthiopien

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 8800:2

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: INSVLA S. LAVRENTII / ’t Eylandt S. Lavrens, ofte Madagascar

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 8900:2

Met zijn beschrijvingen van ‘Het Koningkryck Abissinen’, ‘Neder-Aethiopien’ en ‘’t Eylandt S. Laurens ofte Madagascar’ begeeft Joan Blaeu zich in terra incognita. Enkel de VOC-kolonie Kaap de Goede Hoop in het zuiden van Afrika is op dat moment (1665) in Nederlandse handen en dan nog maar een klein decennium. Over de rest van dit gebied, dat nu grofweg Oost- en Zuid-Afrika en het eiland Madagaskar omvat, was nog niet zo veel bekend in West-Europa. Dat is ook te zien aan de manier waarop de kaarten zijn ingetekend. De kustlijnen zijn redelijk gedetailleerd, maar de binnenlanden zijn veel minder nauwkeurig.

Wat Blaeu beschrijft, is beknopt. Aan de regio’s Abissinen en Neder-Aethiopien besteedt hij slechts vier pagina’s. Toch is er in bronnen uit de tijd van Blaeu meer te vinden over de gebieden dan Blaeu zijn lezerspubliek voorschotelt. In Naukeurige beschrijvinge der Afrikaensche gewesten van Olfert Dapper uit 1668 worden aan ‘Opper-Ethiopien, anders Abysinnie of Paep-Jans-Lant’ veel meer pagina’s gewijd. Toch komen beide auteurs overeen. Zowel Blaeu als Dapper focussen op de aanwezigheid van het christendom in dit gebied. Beiden schrijven dat dit te danken is aan Priester Jan, volgens Blaeu ‘eenen patriarch, die de opperste is van de Geestelijcken, die van een vroom en oprecht leven moet sijn, wel geleert, en van hoogen ouderdom.’ De mythe rond Priester (ook wel: Pape) Jan ontstond in de Middeleeuwen. Priester Jan zou als keizer over Ethiopië heersen en bondgenoot zijn in de strijd tegen de moslims in het gebied. In 1681 toonde de Duitse oriëntalist Hiob Ludolf aan dat Priester Jan een verzonnen figuur was. Ten tijde van Blaeu en Dapper had de mythe nog zijn aantrekkingskracht.

Aan Madagaskar wijdt Blaeu negen pagina’s. Wat meteen tot de verbeelding spreekt, is de naamgeving van Madagaskar, die Blaeu ter discussie stelt. ‘Het eylandt S. Laurens wordt door de Cosmographi ofte Weereltbeschrijvers Madagascar, door d’inwoonders Madecasa, van Ptolemeus Memutheas, van Plinius Carnea, en van de Persianen en Arabiers Sarandib geheeten; maer de rechte naem is Madecasa.’ De Europese naamgeving Sint-Laurens, die Blaeu gebruikt boven de naam Madagaskar, wordt door Dapper verklaard. Het is vernoemd ‘na den eersten ontdekker’, die Laurens Almeide heette. Beide schrijvers refereren daarnaast aan klassieke schrijvers als Ptolemaeus, de Perzen en Arabieren, die het eiland ook kenden. De naam Madagaskar kwam in de tweede helft van de zeventiende eeuw wel in zwang, want volgens Dapper kenden de meeste landbeschrijvers deze naam wel. Het is gebaseerd op de naamgeving in de eigen taal: Madekase of Madecasa.

Zowel Dapper als Blaeu beschreven het continent Afrika vanuit Amsterdam. Zij haalden hun kennis uit het werk van andere Europeanen. Het zou nog eeuwen duren eer de stem van de beschrevene, de volkeren van Oost- en Zuid-Afrika en het eiland Madagaskar, een plek kreeg in westerse literatuur over deze gebieden.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Mukherjee, R. (2018). “People, Places, and Mobility: The Strange History of Prester John across the Indian Ocean”, Asian Review of World Histories, 6 (2), pp. 258-276.

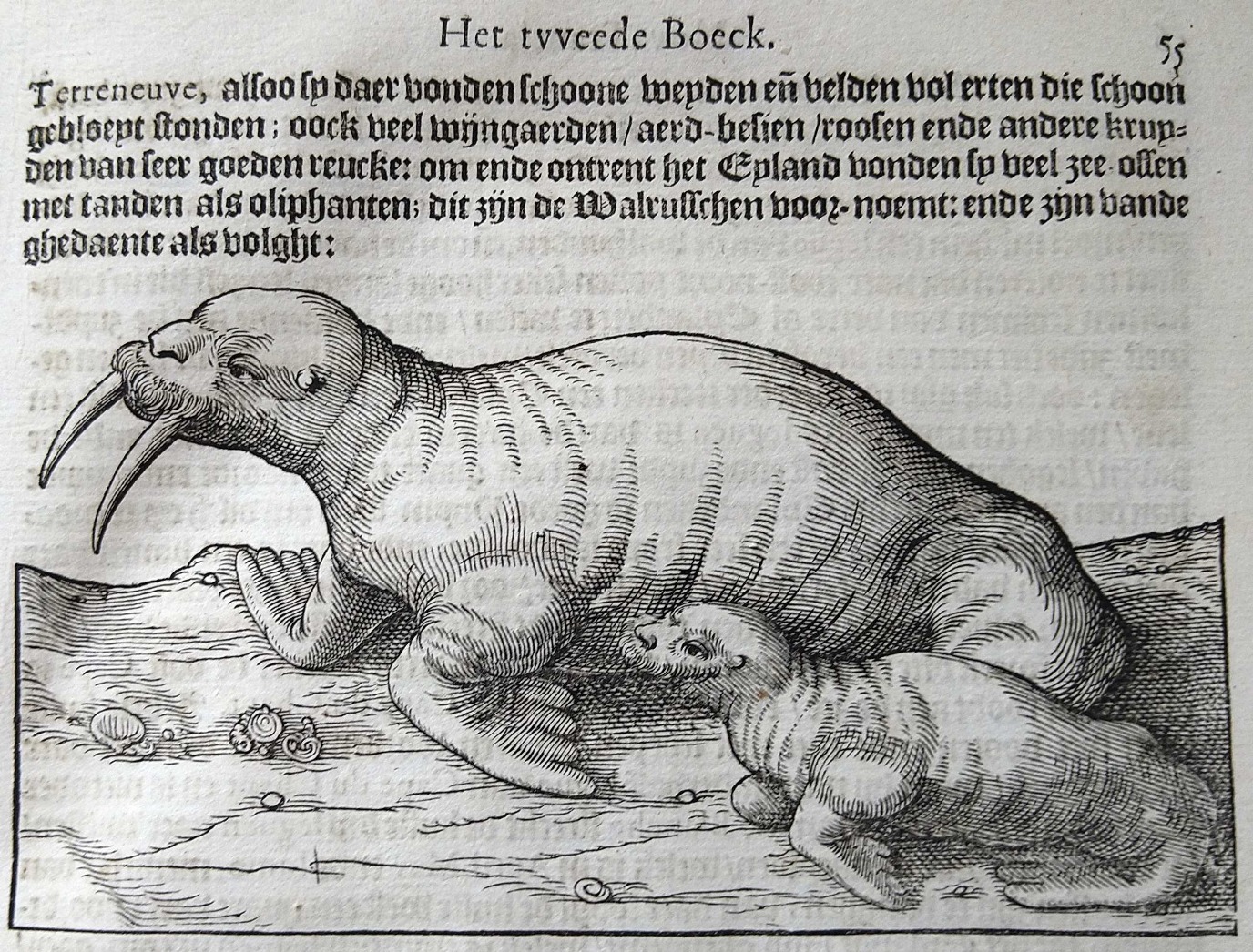

Canada, door Pascal Oskam

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: EXTREMA AMERICÆ VERSVS BOREAM / Nieu Vranckryck, met de bygelegen Landen

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9130:2

Nieu Vranckryck of Nieuw Frankrijk was in de tijd van Blaeu een regio die vandaag de dag bekend staat als het oosten van Canada met bijgelegen eilanden. Het gebied strekte zich uit vanaf de kust van Noord-Amerika tot Newfoundland en Labrador.

Deze regio, als eerste “ontdekt”, bewoond en gekoloniseerd door Franse kolonisten, stond in de late zestiende eeuw en begin zeventiende eeuw vooral bekend om haar visrijke rivieren en zeeën. Zo schrijft Blaeu: ‘Het heele eylandt is doorsneden met verscheyde rivieren, en loopende wateren, die seer goede visschen voortbrengen, onder andere salmen, alen, en, boven alle, uytnemende goede voorens.’ Verder was de lucratieve walvisvangst een belangrijke factor voor de Franse aanwezigheid. Hierbij kreeg men hulp van de oorspronkelijke bevolking die in de beschrijvingen van Blaeu ‘wilden’ worden genoemd.

Hoewel het overgrote deel van de beschrijvingen over de natuurlijke historie van Nieuw Frankrijk gaat, heeft Blaeu ook aandacht voor de inwoners: de ‘wilden’. Maar waarom werd de bevolking op deze wijze bestempeld? Het antwoord ligt in de manier waarop de stammen afweken van de “beschaafde” Europese mens: ‘Sy bestieren sich ten meesten deel sonder wetten, sonder burgelijcke instellingen, op wijse der beesten.’ Ook het feit dat deze stammen niet geloofden in God vergrootte de afstand tussen de christelijke Europeanen en de oorspronkelijke bevolking. Volgens Blaeu zagen deze stammen er bovendien uit als barbaren die, zowel in uiterlijke kenmerken (half naakt) als in gewoonten, voor de kolonisten verre van beschaafd waren.

De kennis over het gebied Nieuw Frankrijk verkreeg Blaeu van twee andere kaarten die dit gebied besloegen: Nouvelle France (Samuel de Champlain) en Nova Francia (Johannes de Laet). Blaeu heeft deze kaarten gebruikt voor onder andere namen voor nederzettingen, rivieren en zeeën, als ook voor informatie omtrent de kustlijnen. Voor informatie over de oorspronkelijke bevolking en de natuurlijke historie leunde Blaeu vooral op twee Franse ontdekkingsreizigers genaamd Samuel de Champlain (ca. 1567-1635) en Jacques Cartier (1491-1557). Deze twee ontdekkingsreizigers worden in zijn beschrijvingen meermaals aangehaald. Dit is niet vreemd aangezien Blaeu beschikte over hun reisverslagen, die hij kort toelicht aan het eind van zijn beschrijving over dit interessante gebied bewoond door ‘wilden’.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Jonathan, L.H. (2022). “Translating Empire, Translating Cartier and Léry into English: Text and Context in Comparative Narratives of Expansion and the New World”, Ilha Do Desterro, 75 (2), pp. 45-64.

Caraïben, door Ruben Klijnsma

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: CANIBALES INSVLÆ / D’Eylanden Der Canibales

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9640:2

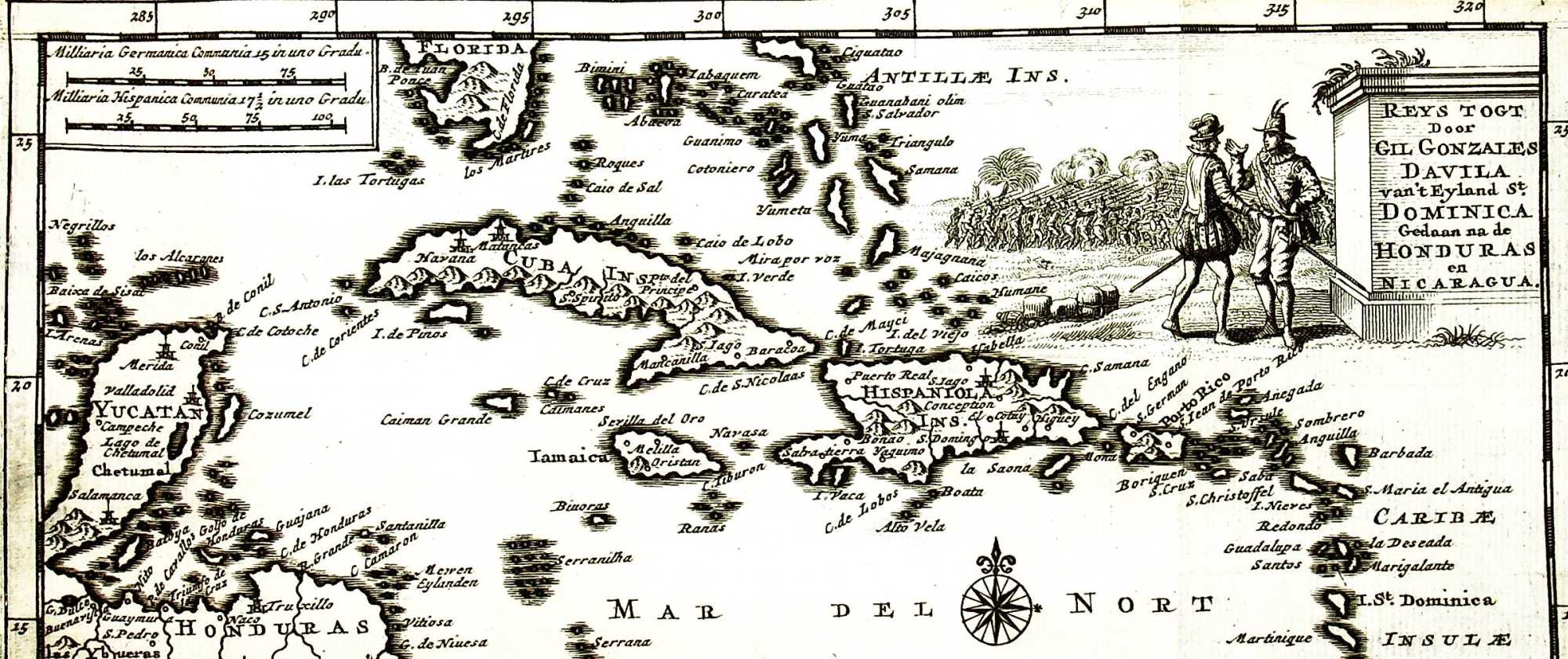

De reizen van Columbus (1451-1506) en opvolgende Europese exploratiereizen richting het westen openden vanaf 1492 voor Europa letterlijk een Nieuwe Wereld. De eerste van deze reizen eindigde bij de eilanden die we nu kennen als Puerto Rico, Haïti, de Dominicaanse Republiek, Jamaica, Cuba en de Caraïben.

De voornoemde eilanden werden door Joan Blaeu op merkwaardige wijze beschreven. Op het eerste oog lijken de beschrijvingen van de eilanden vrij objectief. Allerlei aardrijkskundige, geografische, maar ook economische aspecten worden behandeld. Toch zijn er ook enkele aspecten die voor de hedendaagse lezer bepaalde vragen oproepen.

Het grootste vraagteken kan gezet worden bij het thema kannibalisme, dat, zoals enigszins te verwachten, voornamelijk naar voren komt in de beschrijving van D’Eylanden der Cannibales, vandaag de dag bekend als de Caraïbische eilanden. Blaeu schrijft in deze passage in zijn Grooten Atlas onder andere over ‘mensch-eters’ en ‘wilden’ als hij het heeft over de oorspronkelijke inwoners van het gebied dat wij nu kennen als de Caraïben.

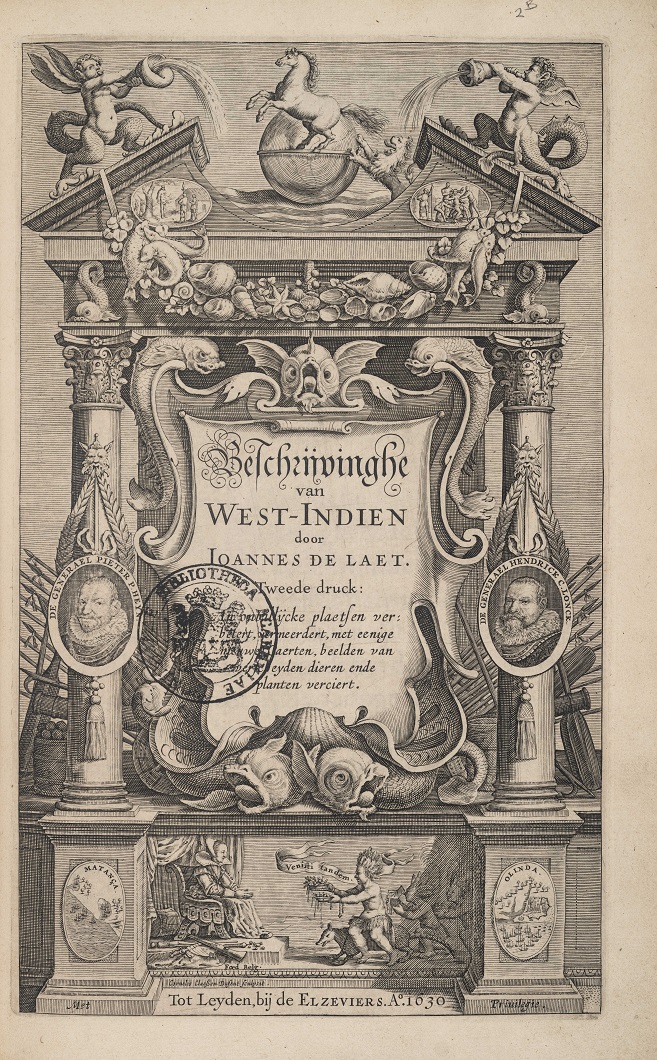

Hoezo werden de oorspronkelijke bewoners van dit gebied op deze manier afgeschilderd in de atlas van Blaeu? Dit komt doordat hij zijn tekst baseerde op de omschrijving van West-Indië door Johannes de Laet. Op meerdere plekken kopieert Blaeu De Laet zelfs letterlijk. In de werken van De Laet komt ook kannibalisme voor, maar hij was niet de enige auteur. In vele reisverhalen en andere verslagen kwamen de kannibalen van de Caraïben voor; ons woord kannibaal is zelfs afkomstig uit dit gebied.

De huidige consensus over dit beladen thema is dat de karakterisering van de bevolking als kannibalen onjuist is. De verhalen van kannibalisme in de Caraïben zijn voornamelijk van horen zeggen en de enige “ooggetuigenverklaringen” die wel authentiek zijn berusten hoogstwaarschijnlijk op culturele misverstanden, incomplete verhalen en/of regelrechte verzinsels.

De karakterisering van de oorspronkelijke bevolking van deze eilanden als kannibalen heeft echter veel impact gehad. Doordat de bevolking werd geduid als ‘wilden’ of ‘kannibalen’ werd de primitiviteit van de bewoners en de zogenaamde superioriteit van de Europeanen benadrukt. Dit leidde onder andere tot de legitimering van de Europese suprematie over en daarmee de decimering van de lokale bevolking in deze regio.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Arens, W. (1979). The Man-Eating Myth: Anthropology & Anthropophagy . New York: Oxford University Press.

Noord-Amerika, door Beaudine Tjerks

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: NOVA BELGICA ET ANGLIA NOVA / Nievw-Nederlandt, En Nievw-Engelandt

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9310:2

De regio Noord-Amerika bestaat voor Joan Blaeu uit de gebieden Nieuw-Nederland, Nieuw-Engeland, Virginia en Bermuda. Blaeu heeft in het achtste deel van de Grooten Atlas onderscheid gemaakt tussen verschillende volkeren uit deze regio. Zo waren er volgens hem “goede” en “kwade” volkeren.

Blaeu heeft zich onder andere kunnen laten beïnvloeden door de Nederlandse en Engelse kolonisten die in dit gebied actief waren. In brieven en reisjournalen hebben kolonisten veelal hun ervaringen en beschrijvingen van de oorspronkelijke volkeren genoteerd. Een voorbeeld is de predikant Jonas Michaëlius (1577-na 1638) die naar het eiland Manhattan in Nieuw-Nederland werd uitgezonden in 1628. Michaëlius beschreef de Manhattans als wild en woest, als verduivelde mensen die niemand anders dan de duivel dienden. Ook Blaeu beschrijft het volk als een vijandelijke natie en vermeldt daarbij dat het volk zich altijd agressief heeft opgesteld tegenover de Hollanders. De ervaringen van Michaëlius kunnen dus duidelijk worden teruggelezen in de Grooten Atlas, wel is Blaeu voorzichtiger in zijn schrijfwijze. Er wordt niet over duivelaanbidders gesproken, maar mensen die vijandelijk waren tegen de Hollanders.

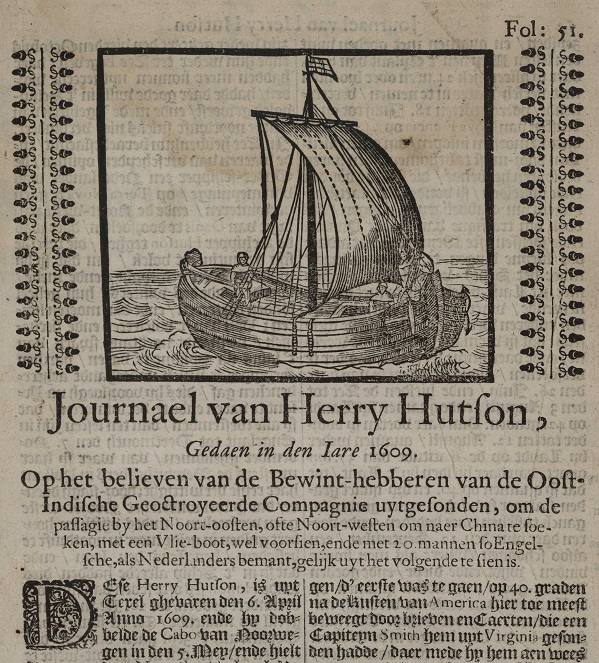

Geograaf en bewindhebber van de West-Indische Compagnie Johannes de Laet had toegang tot vele bronnen waarin het perspectief van de kolonisten werd overgenomen. De Laet baseert zich hierbij zowel op het reisjournaal van de Engelsman Henry Hudson als op het boek The Generall historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (1624). Opvallend is dat Blaeu de beschrijvingen van De Laet vaak kopieert, terwijl Blaeu ook toegang had tot andere bronnen. Blaeu had bijvoorbeeld het boek Good news from New England (1624) kunnen raadplegen, waarin Edward Winslow de gevolgen van de plaag in Nieuw-Engeland beschrijft.

Bermuda werd, in tegenstelling tot de andere gebieden, een typische eilandkolonie zonder oorspronkelijke bewoners. Toch is ook Bermuda van belang wanneer er gekeken wordt naar de ervaringen van kolonisten in de publicatie van Blaeu. Er is sprake van toe-eigening door naamgeving van dieren, op basis van vorm en omstandigheid. Ook de aanplanting van groenten en planten werd belangrijk geacht door de kolonisten. Hoewel Blaeu niet veel aandacht besteed aan toe-eigening door naamgeving, wordt de aanplanting van gewassen wel besproken.

Blaeu was dus selectief in de informatie die hij opnam in de Grooten Atlas. Hoewel Blaeu veel informatie gekopieerd heeft uit het boek van De Laet, hebben andere kolonisten, zij het in getrapte vorm, ook gezorgd voor informatie.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Waterman, K.J., J. Jacobs en Ch.T. Gehring. (2009). Indianenverhalen: de vroegste beschrijvingen van Indianen langs de Hudsonrivier (1609-1680) . Zutphen: Walburg Pers.

Florida, door Phaedra Krol

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: NOVA HISPANIA ET NOVA GALICIA / Niev Spanjen

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9510:2

Spaans Florida komt overeen met de huidige staat Florida in de Verenigde Staten. In de maximale omvang omvatte Nieuw Spanje geheel Centraal-Amerika, maar de Grooten Atlas beperkt zich tot het gebied dat tegenwoordig het zuiden van de Verenigde Staten en Mexico is.

In Amerika troffen de Europeanen allerlei gewassen aan die nieuw voor hen waren en moeilijk gelinkt konden worden met hun bekende gewassen. Blaeu geeft daarom uitgebreide beschrijvingen van planten die in het gebied voorkwamen. Daarbij is vooral aandacht voor het nut van deze planten, door vooral de medicinale werking te benoemen.

Interessanter dan de flora en fauna waren de mensen die in Florida en Nieuw Spanje woonden. Blaeu erkent en beschrijft de verschillen tussen diverse oorspronkelijke volkeren. Zo schrijft hij dat de landen in Florida grote oorlogen tegen elkaar voeren en heeft hij het over verschillende talen die in Nieuw Spanje worden gesproken. Hoewel hij hiermee stelt dat het gebied zou bestaan uit onderscheidende landen en volken, worden alle bevolkingsgroepen door hem bestempeld als ‘indianen’. Met deze generalisatie reduceert Blaeu de verschillende oorspronkelijke volkeren tot één groep.

Blaeu benadrukt in zijn beschrijvingen van het uiterlijk en de cultuur van de volkeren vooral de aspecten waarin zij verschillen van Europeanen. Hun donkere huidskleur verkrijgen de inwoners van Florida volgens Blaeu door een combinatie van het ritueel beschilderen van hun huid met een speciale olie en door de hete zon. Vrouwen die taken uitvoeren die in de ogen van Blaeu als mannentaken kunnen worden bestempeld, noemt hij ‘hermaphrodieten’.

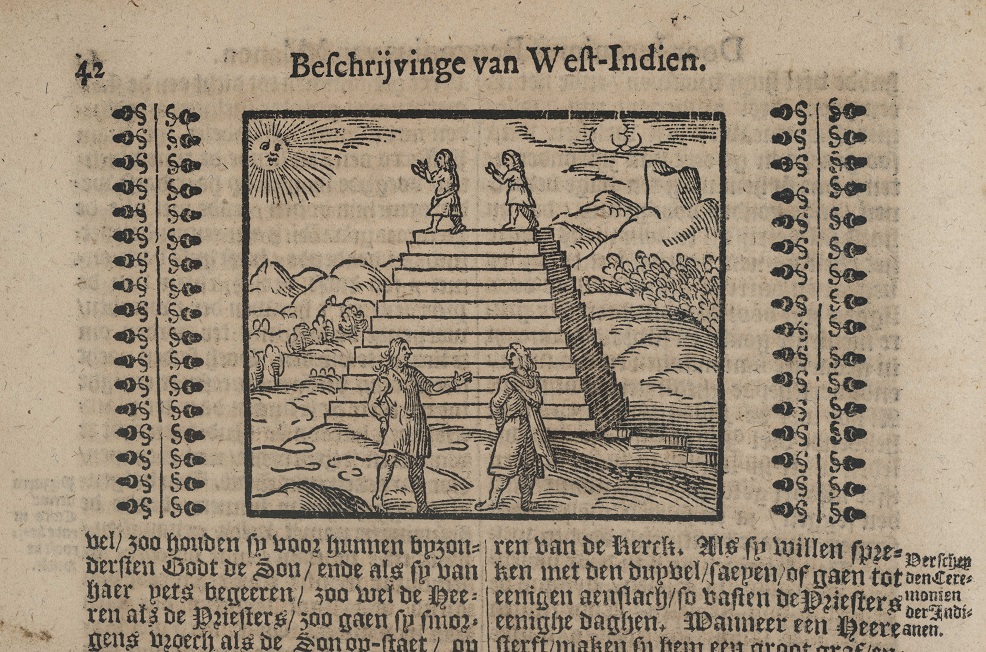

Deze afspiegeling is ook terug te lezen in Blaeu’s beschrijving van religie. Over de religie van de inwoners van Florida schrijft Blaeu: ‘Sy en hebben geen kennis van Godt ofte eenige religie, uytgenomen wat sy sien, als de Sonne en Mane.’ [zij hebben geen kennis van God of enige religie, behalve wat zij zien als de zon en de maan] Hun priesters noemt hij tovenaars en waarzeggers. Zijn afkeer van de “afgoden” die in Nieuw Spanje aanbeden worden, maakt Blaeu met name duidelijk door te beschrijven dat ‘wel ses duysend kinderen van beyde sexen jaerlijcks gedoodt, en den af-goden opgeoffert wierden’ [wel zesduizend kinderen van beide geslachten jaarlijks gedood en aan de afgoden opgeofferd worden].

Ondanks de diversiteit tussen de vele verschillende bevolkingsgroepen in Centraal-Amerika, die deels erkend wordt in de Grooten Atlas, worden de oorspronkelijke volkeren als één groep omschreven, die er duidelijk anders uit ziet dan een Europeaan en een hele andere cultuur heeft dan de Europese.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Botta, S. (2013). Manufacturing Otherness: Missions and Indigenous Cultures in Latin America . Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Honduras, door Casper Colenbrander

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: YVCATAN ET GVATIMALA / Yvcatan en d’Audientie van Gvatimala

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9550:2

De zeventiende-eeuwse Grooten Atlas van Joan Blaeu was één van de meest begeerde boekensets om mee te pronken. Kopers ervan behoorden tot de absolute top van de Europese elite: van rijke Amsterdamse kooplieden tot de Russische tsaar. De Grooten Atlas was geen naslagwerk, zoals de huidige Grote Bosatlas, maar een luxe object.

Toch is de Grooten Atlas wel degelijk een grote bron van kennis. De reeks beslaat honderden kaarten en duizenden bladzijden tekst waarin zo goed als de hele wereld wordt beschreven. Hij geeft inzicht in hoe in de zeventiende eeuw Europeanen naar de rest van de wereld keken. Hierbij is alleen een groot probleem: Blaeu vermeldt nauwelijks zijn bronnen.

Het niet vermelden van bronnen is in de hedendaagse wetenschap een doodzonde, maar in de tijd van Blaeu was dit niet ongewoon. Toch zijn Blaeu’s bronnen herleidbaar. Neem bijvoorbeeld Blaeu’s beschrijving van de Spaanse kolonie Honduras. Hij heeft hiervoor, vrijwel één op één, teksten overgenomen uit de werken van de WIC-bestuurder Johannes de Laet en uit de boeken van Jan Huygen van Linschoten. Dat noemen we vandaag de dag plagiaat.

Wie de beschrijvingen van Blaeu nader onderzoekt, komt er ook achter dat Blaeu nogal een gekleurd beeld schetste. Zo schreef Blaeu over de oorspronkelijke bevolking van Honduras dat deze flink is afgenomen vanwege ‘de inlandse oorlogen en wederzijds doodslaan’. Dat is in lijn met hoe De Laet er ook overschreef. Van Linschoten stelde echter dat de massale sterfte in Honduras het gevolg was van slavernij en uitbuiting. Oftewel, een directe consequentie van het kolonialisme.

Waarom schreef Blaeu meer in lijn met De Laet en niet met Van Linschoten? Dat was zeer waarschijnlijk om zijn lezers niet voor het hoofd te stoten. Blaeu maakte immers zijn atlas voor de Europese elite. Die elite plukte de vruchten van het kolonialisme. Blaeu wilde de kopers van zijn atlas niet voor het hoofd stoten. Zo behoorde tot die beoogde kopers de Spaanse adel, waaronder de koning. Waarschijnlijk zouden die kritiek op hun kolonie in Honduras niet op prijs hebben gesteld.

Blaeu was dus niet alleen onduidelijk over zijn bronnen, hij gaf ook een gekleurd beeld van de wereld. Voor degenen die meer willen weten over de harde kanten van het Europees kolonialisme is er het voor een breed publiek geschreven boek Guns, Germs, and Steel van Jared Diamond (ook in Nederlandse vertaling). Diamond verklaart hoe Europa in de vorige eeuwen dominant werd. Het kolonialisme speelde hierbij een grote rol. Diamond behandelt hierin ook de massale sterfte in Amerika. Dat was een directe consequentie van Europees kolonialisme. Net als Blaeu bestrijkt Diamond zo goed als de gehele wereld in zijn boek, maar in tegenstelling tot Blaeu geeft Diamond wel duidelijk traceerbare referenties.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Diamond, J,M. (1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel: the Fates of Human Societies. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

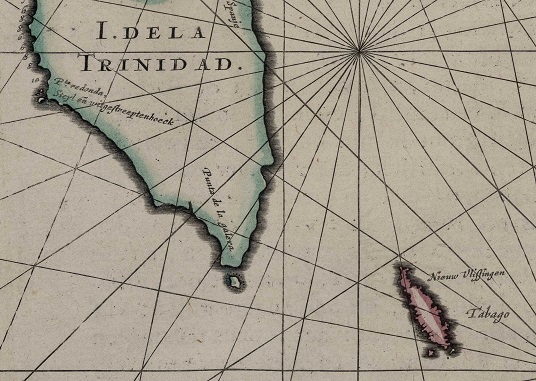

Venezuela, door Lieke Oude Wesselink

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: TERRA FIRMA ET NOVVM REGNVM GRANATENSE ET POPAYAN / Terra Firma, Nova Granada, En Popayan

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9810:2.2

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: VENEZVELA / Niev Andalvzien, En Venezvela

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9830:2.2

Vanaf 1621 werd de Nederlandse handel in het Trans-Atlantisch gebied uitgevoerd door de WIC. In tegenstelling tot de VOC had de WIC niet een absolute grip op de handel in dit gebied. In de gebieden Terra Firma en Venezuela, waar deze kaarten van Blaeu in de Grooten Atlas over gaan, hadden de Nederlanders dan ook geen macht en slechts een beperkte rol in de handel. Deze kaarten gaan over het huidige Colombia en de landengte Panama en Venezuela en Guyana. Deze landen lagen onder koloniaal gezag van het Spaanse Rijk. De Spanjaarden leunden op de zilvervloot die zij hadden opgezet in het Atlantische gebied, en de tweede zilvervloot was de Terra Firma. Deze vloot kwam langs deze gebieden om zilver, goud en andere natuurlijke bronnen te halen en te vervoeren naar Spanje. Nederland was wel een beperkte tijd aanwezig in Venezuela om zout en rood hout te importeren, voordat de Spanjaarden hier een einde aan maakten.

Door de beperkte aanwezigheid van de Nederlanders in deze gebieden was er in de tijd van Blaeu ook niet veel aandacht voor. Daarnaast was er al een gedetailleerde beschrijving uitgegeven door Johannes De Laet, genaamd Beschrijvinghe van West-Indien. Blaeu besloot voor deze gebieden grotendeels te leunen op de beschrijvingen van De Laet. Ook de kaart die hoort bij de teksten van Blaeu over deze gebieden is overgenomen van De Laet.

Voor de teksten over Venezuela en dan specifiek de gebieden waar de “Hollanders” zout hebben gehaald heeft Blaeu wel actuelere tekst toegevoegd. Hieruit blijkt dat bij aanwezigheid van de Nederlanders Blaeu er wel belang bij had om nieuwere, actuelere teksten te selecteren. In de beschrijvingen bij de kaart van Terra Firma gaat het voornamelijk over informatie die relevant was voor de zilvervloot. Zo gaat het over de belangrijke steden voor de zilvervloot zoals de eindbestemming Nombre Dios in Panama, of de stad Cartagena die als een belangrijke plek diende voor de vloot, omdat er een beschutte en goed beveiligde baai lag waar schepen proviand konden inslaan.

Over de volkeren wordt voornamelijk geschreven dat ze kwaadaardig zijn of kannibalen, maar ook komen er stukjes tekst in de kaarten van Blaeu voor over bijvoorbeeld collaboratie tussen de oorspronkelijke volkeren en de Spanjaarden. De Spanjaarden hadden aanvankelijk de intentie om het gebied en de bevolking te koloniseren, maar zij gingen later over op het creëren van Europese enclaves.

Het blijft interessant waarom Blaeu er specifiek voor heeft gekozen om bepaalde informatie wel te over te nemen in zijn passages in de Grooten Atlas en andere voor handen zijnde informatie niet.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Emmer, P.C., & Gommans, J.J.L. (2020). "The Atlantic World", in: The Dutch Overseas Empire, 1600–1800, pp. 125–244

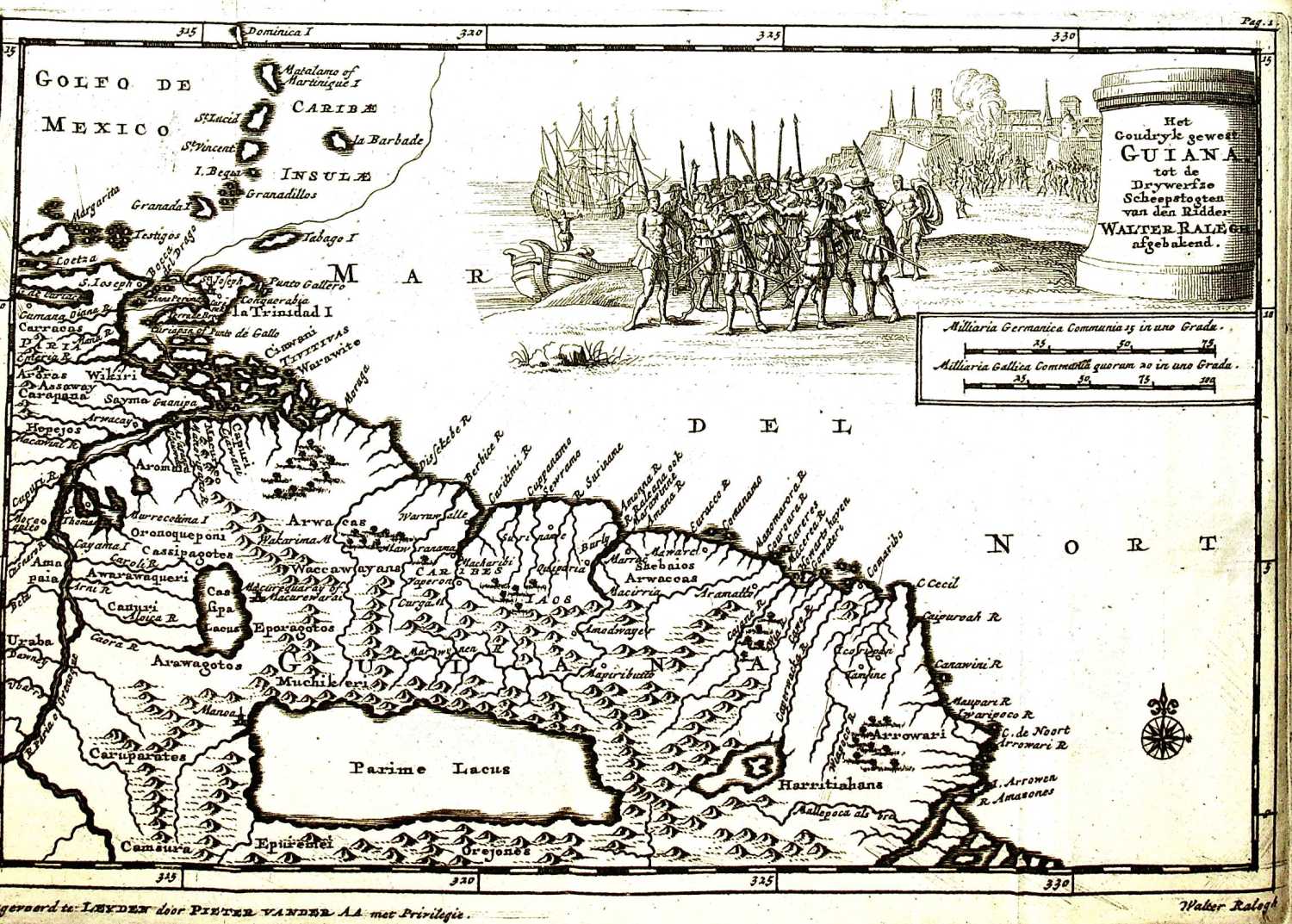

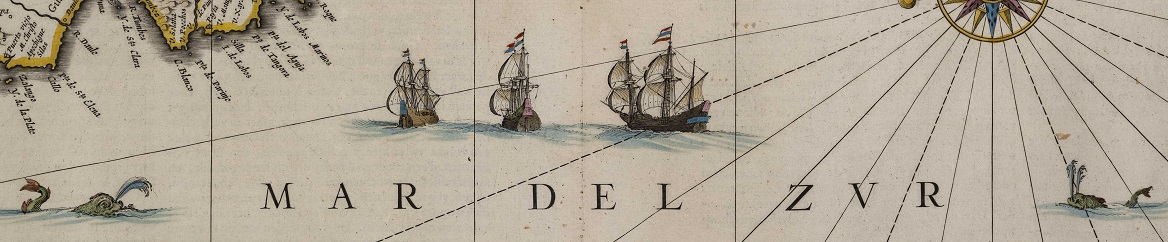

Guyana's, door Sam Beereboom

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: GVIANA SIVE AMAZONVM REGIO / Gvaiana, Oft De Wilde Kvst

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9840:2.2

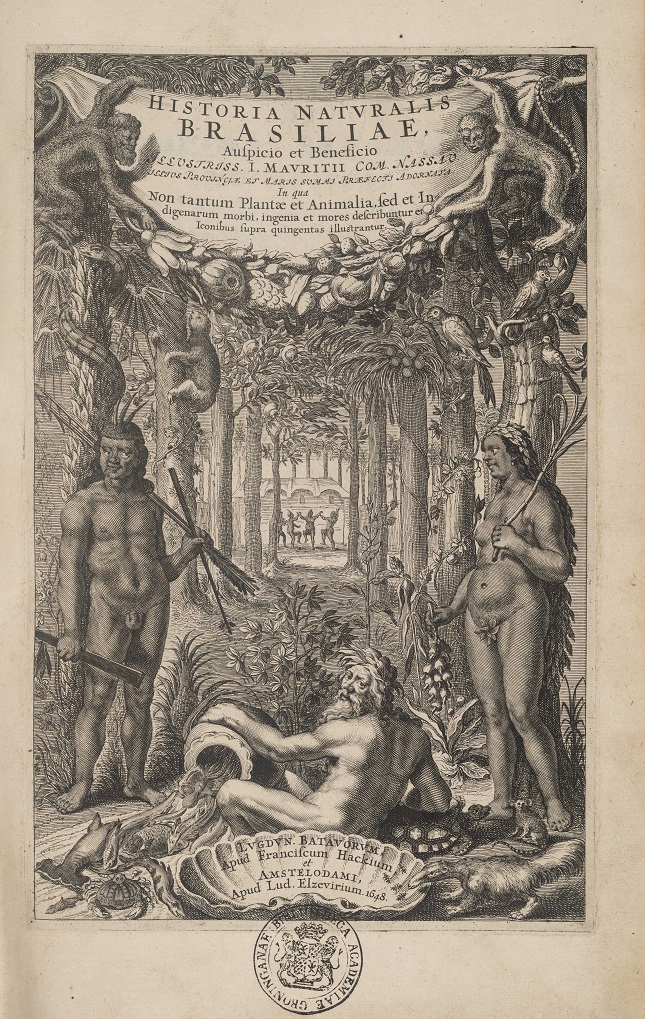

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: BRASILIA / Brasil

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9850:2B

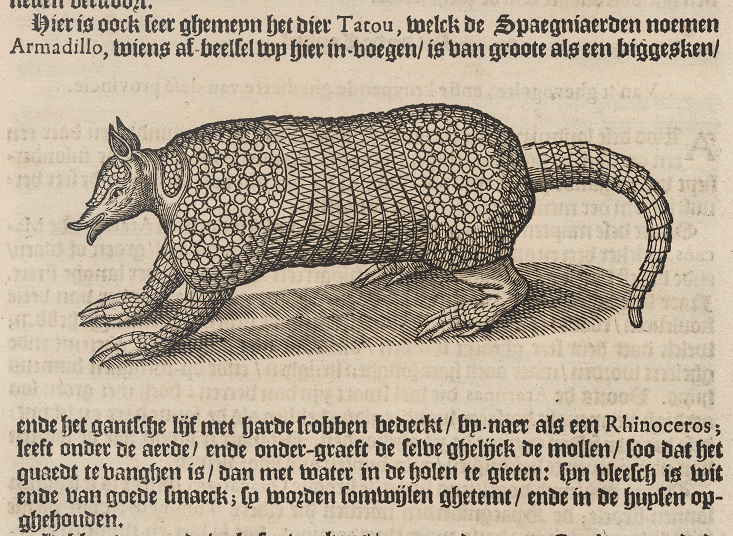

De regio Guiana (de Wilde Kust) beslaat het gebied tussen de rivieren Orinoco en Amazone. De regio Brasil beslaat (gedeeltelijk) het huidige Brazilië.

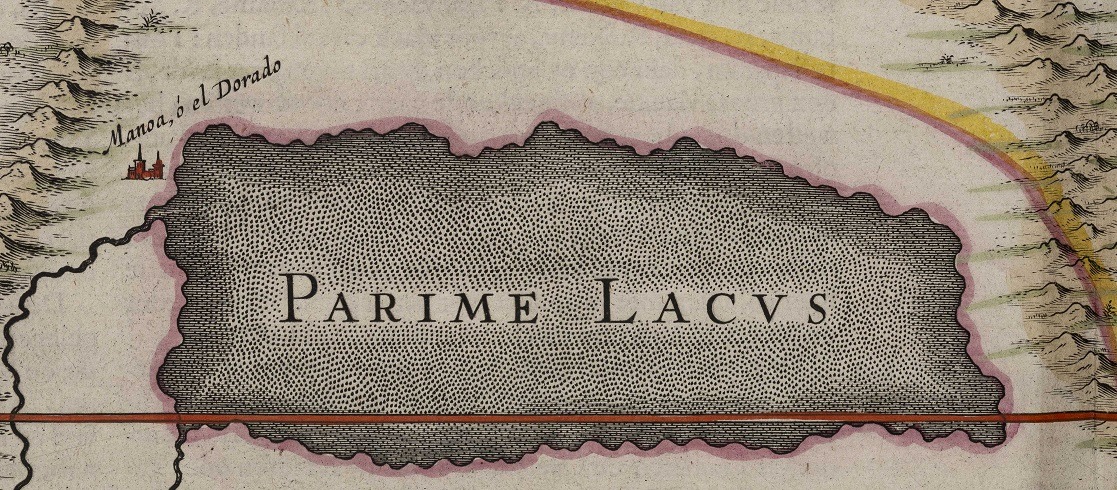

In de teksten uit de Grooten Atlas over deze gebieden is er sprake van een schijnbare tegenstelling. Enerzijds was er een sterke bewondering voor de “schatten” van de exotische gebieden in Amerika. Zo refereert Blaeu in de tekst naar de mythe van El Dorado: de Vergulde Man. De Spanjaarden geloofden dat een “indiaanse” hoofdman, bedekt met goud, werd ingewijd in een meer dat men in deze regio situeerde. Verschillende expedities werden begin zestiende eeuw opgezet om hem te vinden, waarbij de mythe uitgroeide van een man tot een stad, een land, en ten slotte een koninkrijk van goud. Tastbaardere, aardsere “schatten” zoals maïs, tarwe, peper en vruchten waren zeer gewild. Blaeu schrijft dat er in de regio nuttige geneesmiddelen voorhanden waren: “'t Sap van het blad genaemt Icari, is goedt tegen de pijn in ’t hooft.”

Aan de andere kant wordt (de leefstijl van) de oorspronkelijke bevolking van de gebieden — vanuit een westers perspectief — afgekeurd. Blaeu benoemt dat de mensen veelal naakt lopen, geen religie aanhangen en mensenvlees eten. Ook beeldde hij op zijn wereldkaart uit 1648 kannibalen af in Zuid-Amerika. De beschrijving van de verschillende Zuid-Amerikaanse volkeren door Blaeu komt nauw overeen met de beschrijvingen die Johannes de Laet in 1625 reeds publiceerde. Hoogstwaarschijnlijk is dit de bron voor Blaeu geweest. De Laet beschrijft de volkeren als gewelddadig en zonder enige vorm van beschaving. Doordat dergelijke beschrijvingen in meerdere contemporaine bronnen voorkomen, mag worden aangenomen dat dit de heersende visie representeert.

De historicus Stephen Snelders schreef in 2012 over de bovengenoemde bewondering voor geneesmiddelen en de Europese visie op Indianen. Hierbij haalt hij Willem Piso (1611-1678), een grondlegger van de tropengeneeskunde, aan. Piso stelde dat de Europeanen ‘natuurlijk’ bepaalden welke geneesmiddelen en geneeswijzen nuttig waren, aangezien het ging om zaken die hun oorsprong vonden in een ‘barbaarse omgeving’. De kern van de tegenstelling, en de verklaring voor het naast elkaar bestaan van interesse en afgunst, komt daarvandaan. De Europese kolonisten redeneerden namelijk vanuit hun eigen perspectief. Al wat er gevonden werd in de “Nieuwe Wereld”, werd — zowel bewust als onbewust — getoetst aan de Europese norm. Dat wat daarbinnen paste, zoals de benodigde geneesmiddelen om te kunnen overleven in Amerika, werd bewonderd en begeerd. Dat wat daarbuiten viel, zoals de vermeende onbeschaafde levensstijl van de indianen, werd afgekeurd.

De Grooten Atlas van Blaeu is een spiegel van de zeventiende-eeuwse maatschappij waarin Europese suprematie algemeen gedachtegoed werd. De kennis van oorspronkelijke volkeren werd terzijde geschoven, of onbenoemd toegeëigend in wetenschappelijke verhandelingen, zoals die van Piso. De “ander” werd niet ten volle erkend. Deze handelwijze droeg bij aan Westers suprematiedenken, dat deels tot op de dag van vandaag voortduurt.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Snelders, S. (2012). Vrijbuiters van de heelkunde: op zoek naar medische kennis in de tropen, 1600-1800 . Amsterdam: Atlas.

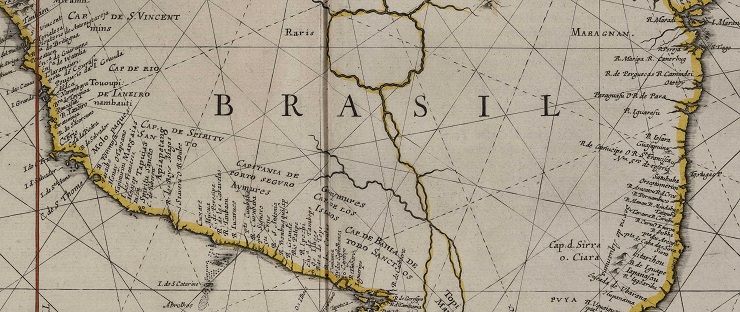

Brazilië, door Niek Zeinstra

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: BRASILIA / Brasil

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9850:2B

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: SINVS OMNIVM SANCTORVM / Gouvernement van De Bahia De Todos Los Santos

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9855:2.2

Joan Blaeu beschrijft met zijn teksten het huidige Brazilië en het gouvernement van Bahia. Vanuit de contemporaine bronnen valt te zien welke indrukken op de Westerse wereld een blijvende invloed hebben gehad en hoe deze de perceptie van Brazilië hebben gevormd.

Naast Blaeu schreven ook André de Thevet en Johannes de Laet over de representatie en beeldvorming van de inheemse bevolking van Brazilië in de zeventiende eeuw. Specifiek focussen de bronnen op drie stammen, waarbij de verdeling er min of meer op neerkomt dat Blaeu zich met name richt op de Petivares, Thevet op de Tupinambá-stam en De Laet op de Maraquites.

Volgens Blaeu was de stam Petivares, in tegenstelling tot andere stammen, minder “barbaars”. Ze hadden — aldus Blaeu — lichaamsdecoraties, zoals gaten in de lippen, maar waren minder religieus. Ze voerden oorlog tegen de Portugezen, aten mensenvlees en vestigden zich rond Parayba. Blaeu schreef niet alleen over de Petivares, ook over de Tupinambá en de Maraquites. Blaeu schreef over alle drie de stammen, maar heeft hoogstwaarschijnlijk zijn informatie over de Tupinambá en de Maraquites te danken aan de geografen Thevet en De Laet.

Zo geeft de Franse geograaf en reiziger André de Thevet (1516-1590) ons inzicht in de Tupinambá-stam door te focussen op verschillende aspecten van hun levenswijze. Hij bestudeerde in situ lichaamsdecoraties, jachtgewoonten, sociale structuren en eetgewoonten van de Tupinambá. Thevet beschrijft gedetailleerd hoe de Tupinambá hun lichaam versieren met sieraden, verf en mogelijk tatoeages, waarbij deze versieringen niet alleen dienen als expressie maar ook als identiteitsuiting en rituele praktijk. In zijn reisverslag belicht Thevet ook de jachtgewoonten van de Tupinambá, waarbij hij ingaat op wapens, technieken en mogelijke rituele aspecten rondom het jagen. De sociale structuur van de Tupinambá, inclusief stamorganisatie, leiderschapssystemen en besluitvorming, wordt door Thevet belicht, wat inzicht geeft in de sociale dynamiek van de stam. Hij geeft gedetailleerde beschrijvingen van hun dieet, voedselbereidingstechnieken en mogelijke rituelen voor voedselconsumptie. Het noemen van het eten van mensenvlees is een controversieel element dat zowel Thevet als andere auteurs in de vroegmoderne periode vaak benoemen.

Johannes de Laet, die anders dan André de Thevet nooit in Amerika is geweest, beschrijft in zijn werken de fysieke kenmerken, kleding en lichaamsversieringen van de Maraquites. De Laet geeft ook inzicht in de cultuur en tradities van de Maraquites, met aandacht voor rituelen bij belangrijke levensgebeurtenissen, religieuze praktijken en overtuigingen die kenmerkend waren voor hun cultuur.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Eakin, M.C. (1997). Brazil: the Once and Future Country . Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Pernambuco en Paraiba, door Noah Wubs

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: PRÆFECTVRÆ PARANAMBVCÆ PARS BOREALIS / ‘t Gouvernement van Fernambuco

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9850/3:2D

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: PRÆFECTVRÆ DE PARAIBA ET RIO GRANDE / ‘t Gouvernement van Paraiba

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9850/4:2D

De gouvernementen Pernambuco en Paraiba liggen in de oostelijke punt van het Zuid-Amerikaanse continent in het huidige Brazilië. In de regiobeschrijvingen van Blaeu wordt het gebied uitvoerig beschreven. Zo worden er steden, dorpen, rivieren en grondstoffen genoemd. Een belangrijk product uit het gebied was suiker. Dit komt ook tot uiting in de tekst en prenten bij de kaarten. Verschillende suikerrietplantages en raffinaderijen worden genoemd, in een van de prenten in de atlas wordt zo’n raffinaderij getoond. Suiker werd vrijwel exclusief voor de Europese markt verbouwd en was commercieel zeer lucratief. In de late zestiende en eerste helft van de zeventiende eeuw was beheersing van (delen van) Pernambuco en Paraiba dan ook aanleiding tot Europese conflicten.

Zo worden door Blaeu verschillende machtswisselingen genoemd in de tekst. De Fransen waren de eersten die actief waren in dit gebied, maar werden door de Portugezen met behulp van de oorspronkelijke bevolking in 1584 uit dit gebied verdreven. In de jaren dertig van de zeventiende eeuw begonnen de Nederlanders met hun verovering van de suikerproducerende gebieden. De Nederlandse expansie kwam in een stroomversnelling door de verovering van het Portugese steunpunt Olinda in 1632. Maar de aanwezigheid bleek van relatief korte duur. Door hevige tegenstand van Portugese kolonisten en oorspronkelijke bewoners moesten de Nederlanders in 1654 definitief hun aanwezigheid in Brazilië opgeven. De herovering door de Portugezen, ook al verscheen de Grooten Atlas ruim een decennium later, blijft in de tekst geheel onvermeld. Ook op de bijbehorende kaart is de Nederlandse aanwezigheid nog volop zichtbaar.

Aan de oorspronkelijke bewoners die leefden in het gebied worden slechts enkele passages gewijd. De Amerindianen worden door Blaeu steevast “wilden” genoemd. Helemaal niet genoemd worden de joodse kolonisten. Uit historisch onderzoek weten we dat zij een grote ondersteunende rol hebben gespeeld bij de Nederlandse expansie in de Braziliaanse gouvernementen, maar ze blijven door Blaeu onvermeld. Dezelfde marginalisering ondergaan slaafgemaakte Afrikanen, die werkten op de suikerrietplantages en in de molens. Aandacht is er voor de Europese aanwezigheid, zij het Frans, Portugees of Nederlands, in het gebied en (met name) welke lucratieve producten er vandaan kwamen.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Lint, J. de (2020). Pernambuco, the Dutch in Brazil 1624-1654 . Zwaag: Pumbo.

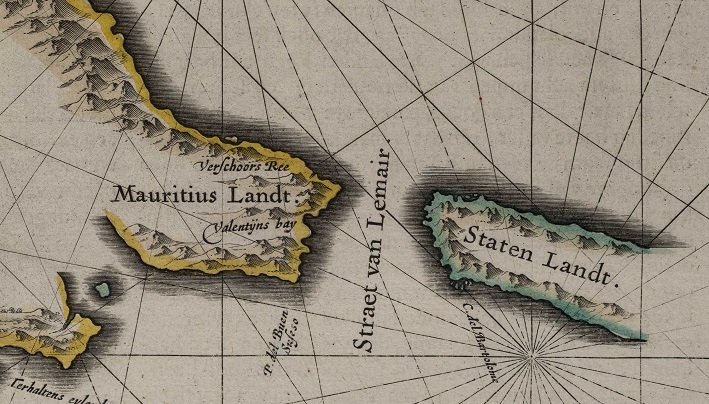

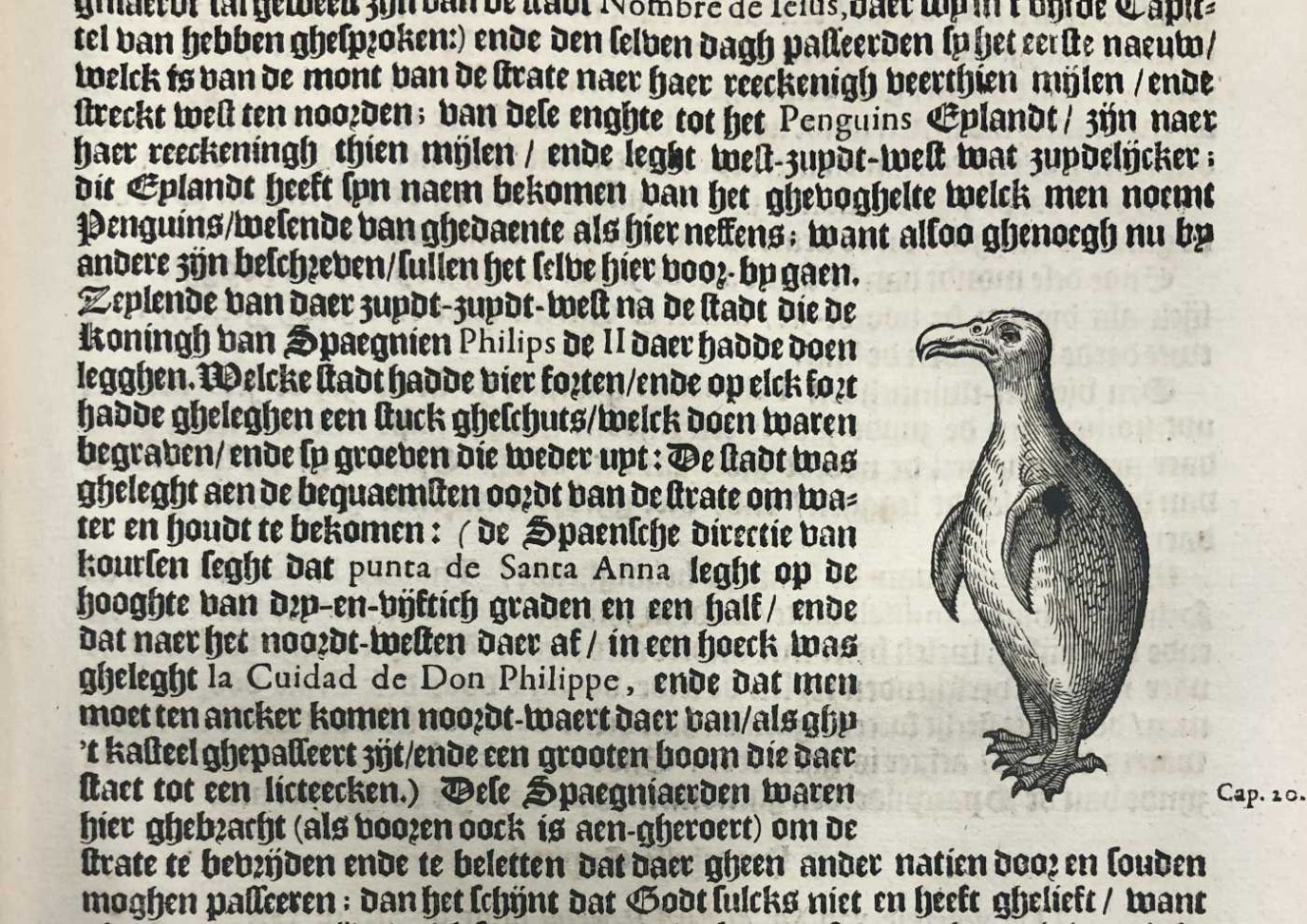

Zuid-Amerika, door Wout Tannemaat

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: TABVLA MAGELLANICA / Strate Le Maire

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9950:2B

Het onderste gedeelte van Zuid-Amerika, dat wij nu Argentinië, Chili, Paraguay en Uruguay noemen, was ten tijde van Blaeu’s Grooten Atlas ruim honderdvijftig jaar gekoloniseerd door de Spanjaarden. Conquistadores zoals Francisco Pizarro (1478-1541) en zijn opvolger Pedro Valdivia (1497-1553) veroverden op bloedige wijze grote gebiedsdelen voor goud, glorie en God, ongeveer in deze volgorde.

Het gebied is uitgestrekt en divers, maar krijgt in de Grooten Atlas slechts twaalf pagina’s toebedeeld. Zes van de pagina’s bevatten een summiere natuurhistorische beschrijving, informatie over grondstoffen, hoe de Spanjaarden er steden stichtten en andere ontdekkingsreizen. De oorspronkelijke bevolking komt alleen voor in de context van extractie, om te laten zien hoe groot het gezag was van de Spanjaarden of door te noemen welke naam een bepaalde plaats heeft in haar eigen taal. Welke mensen dat dan zijn, of wat hun culturele achtergrond is, blijft onvermeld. In de regiobeschrijving worden alle oorspronkelijke bewoners van dit gedeelte van Zuid-Amerika gecategoriseerd als “indianen”.

Als er geen goud of zilver te halen viel, zag Blaeu het als een irrelevant gebied. Hij beschrijft namelijk wel wat de beste routes naar Potosí waren in zijn passage over de provincie Rio de la Plata. Het was voor tijdgenoten van Blaeu algemeen bekend dat in Potosí mijnen lagen waar een groot gedeelte van het Spaanse zilver vandaan kwam dat naar Europa werd verscheept. De verovering van de Spaanse zilvervloot door Piet Hein in 1628 heeft deze historie onderdeel gemaakt van ons collectief geheugen.

De overige zes pagina’s zijn kaarten van de gebieden waarbij vooral de kaart van Vuurland opvalt omdat deze amper is ingevuld, maar wel allerlei Spaanse en Nederlandse namen draagt waarbij ook “indianen” zijn afgebeeld aan de rand. Het is typerend voor de marginalisering van deze gebieden en de oorspronkelijke volkeren die er leefden.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Burkholder, M.A., & Johnson, L.L. (2010). Colonial Latin America (7th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Peru, door Jorik Davids

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: CHILI / Chili

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9920:2A.2

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: PERV / Perv

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 9820:2.2

De Grooten Atlas, een fascinerend werk gemaakt door cartograaf en uitgever Joan Blaeu, toont meer dan alleen prachtige versierde kaarten. De aanvullende informatie naast deze kaarten onthult ook hoe tijdgenoten van Blaeu keken naar de grote mysterieuze wereld.

Deze tekst richt zich in het bijzonder op de wijze waarop Blaeu de regio’s van Chili en Peru omschreef. De regio’s Chili en Peru in de Grooten Atlas omvatten het huidige Noord-Chili, Peru, Ecuador en gedeelten van Bolivia en Colombia. Hieronder vallen de oorspronkelijke leefgebieden van de Inca’s en vele andere volkeren, zoals de Araukaners (Mapuche) en de Aymara.

Blaeu gebruikt herhaaldelijk de categorie “indianen” om te verwijzen naar de oorspronkelijke bevolking van Chili en Peru. Dit is een term die is blijven hangen als gevolg van de misvatting van Columbus dat hij India had bereikt. Het lijkt erop dat alleen de Inca’s, alhoewel zij ook werden gezien als “indianen”, genoeg respect of verwondering hadden opgewekt om genoemd te worden bij een specifieke volksnaam. De andere oorspronkelijke bewoners kregen simpelweg het label “indiaan” opgeplakt. Positieve opmerkingen over deze oorspronkelijke bewoners zijn zeldzaam in de teksten van Blaeu, maar zijn wel te vinden in de beschrijvingen van de Inca's. Opmerkingen over de andere “indianen” richten zich grotendeels naar het contemporaine perspectief dat vooral (op een negatieve wijze) de verschillen benadrukte.

Ondanks het feit dat de Spanjaarden in hun exploitatiesysteem gebruikmaakten van de oorspronkelijke bewoners als goedkope arbeidskrachten, ontbreekt in Blaeu's teksten een vermelding naar een belangrijke groep die eveneens aanwezig was, maar niet genoemd wordt. Namelijk de tot slaaf gemaakte mensen uit Afrika, die via de Atlantische Oceaan naar Zuid-Amerika waren gebracht. Na de afschaffing van de slavernij op de oorspronkelijke “indianen” in 1542 was deze groep in grote aantallen aangevoerd om dwangarbeid te leveren.

Alhoewel de Nederlanders geen kolonie hadden in deze regio, komen zij toch een paar keer voor in de teksten van Blaeu. In de eerste helft van de zeventiende eeuw waren zij namelijk, vanuit hun basis in Mauritsstad (Recife), actief in het plunderen van de Spaanse koloniën. Opmerkelijk is dat de grootschalige poging van de West-Indische Compagnie (WIC) om via de Chili-expeditie van 1643 een eigen kolonie te stichten in dit gebied onvermeld blijft. Vermoedelijk was dit een bewuste keuze van Blaeu, om zo de lezer niet verder te belasten met het collectief Nederlands trauma dat deze mislukte expeditie teweeg had gebracht.

Blaeu noemt voornamelijk de verdiensten van de Spanjaarden in de regio’s. Hij schetst een haast romantisch beeld van de rijkdommen die de landen te bieden hadden, maar benoemt vrijwel niet dat de wijze waarop Spanje haar dominantie had verkregen met veel bloedvergieten gepaard was gegaan. Er klinkt haast een natuurlijke vanzelfsprekendheid van de Spaanse (of breder: de Europese) suprematie in de beschrijvingen van Blaeu.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Henk den Heijer (2015). Goud en Indianen - Het journaal van Hendrick Brouwers expeditie naar Chili in 1643 . Zutphen: Walburg Pers.

Molukken, door Rozemarie Fokkema

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: MOLVCCÆ INSVLÆ CELEBERRIMÆ / Molvccen

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 8560:2.2

De Molukken beslaan in de Grooten Atlas de eilanden Ternata (Ternate), Tidora (Tidore), Motir (Moti), Machian (Makian) en Bachian (Batjan), gelegen in de huidige Noord-Molukken. Uit de titel van het bijbehorende kaartbeeld, Moluccae insulae celeberrimae (Nederlands: de wereldberoemde Molukse eilanden), blijkt al dat deze relatief kleine eilanden reeds bekend waren in de tijd van Blaeu. Reden voor die “roem” waren de specerijen die hier groeiden, waarvan sommige, zoals de kruidnagel, alleen in dit gedeelte van de wereld voorkwamen. Europese en Aziatische handelaren begeerden een deel in de zeer lucratieve specerijenhandel.

Blaeu schenkt in de regiobeschrijving veel aandacht aan de ‘byzondere’ kruidnagelboom. Kenmerken als waar en wanneer deze groeit, maar ook hoe de kruidnagel geplukt en gedroogd moet worden, krijgen uitvoerige aandacht. Deze aandacht wijst op de beoogde handelsrelevantie van de kruidnagel. De vruchtbaarheid wordt bijvoorbeeld gemeten in commerciële termen. Zo zijn de kruidnagelbomen zo vruchtbaar ‘dat men van eenen twee baren plukt, dat is, 1250 Hollandtsche ponden.’

Daarnaast staat een groot deel van de beschrijving in het teken van concurrerende buitenlandse machten die invloed probeerden te krijgen op de eilanden. Zo geeft Blaeu aan dat Arabische kooplieden al eerder handelden in dit gebied en dat de Molukse bevolking de islam en het Arabische schrift deels van hen hadden overgenomen. Verder leidden de aanwezigheid van Nederlandse, Spaanse en Portugese handelaren op de Molukse eilanden tot conflicten in de late zestiende en zeventiende eeuw. Zij zochten namelijk alle drie naar een monopolie op de specerijenhandel in dit gebied.

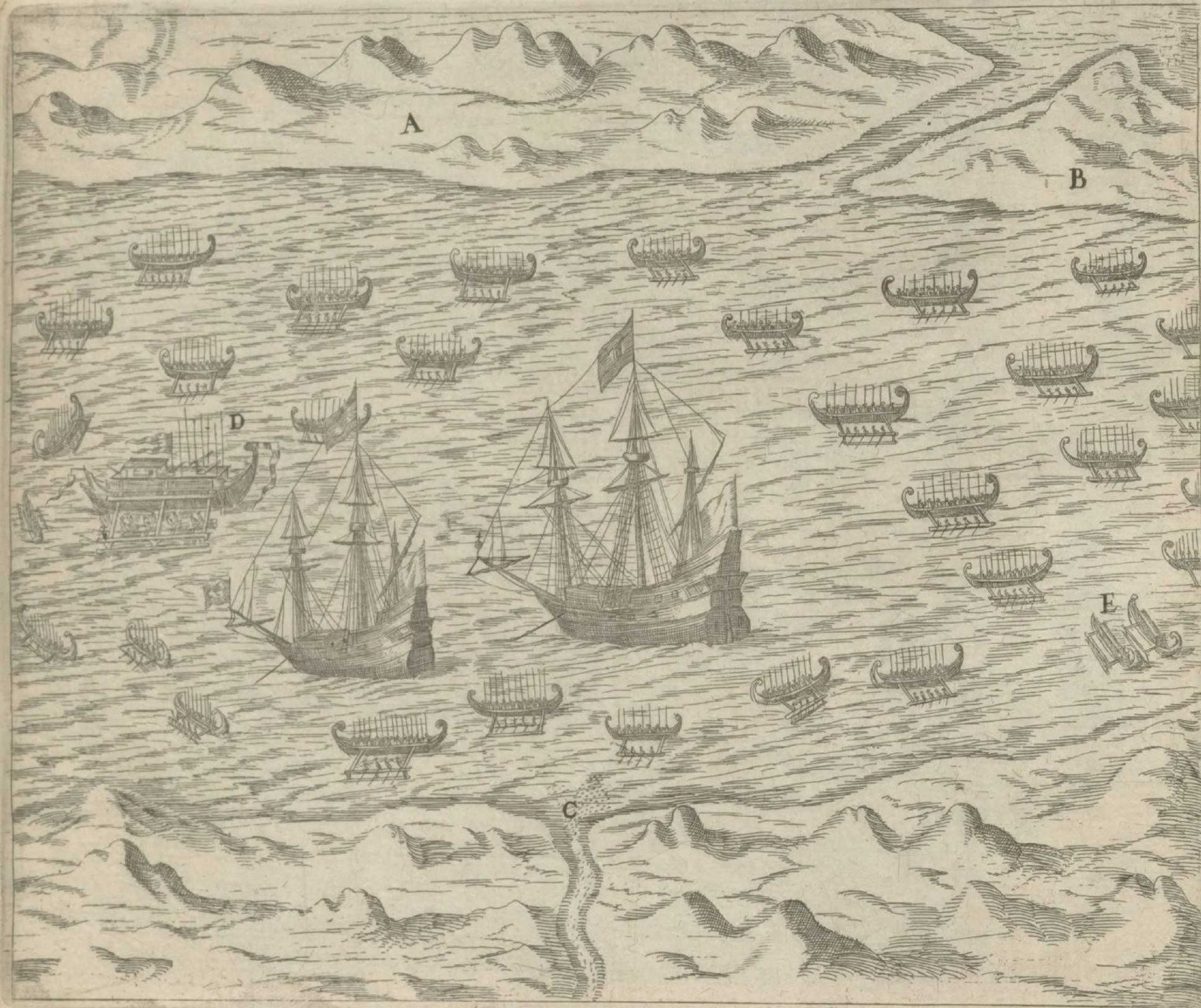

Zo schrijft Blaeu over het bondgenootschap tussen het eiland Tidora en de Portugezen, en tussen het eiland Ternata en de Nederlanders. Deze buurlanden, volgens de beschrijving ‘soo na by malkanderen, dat men met een grof-geschuts kogel van d’een kust de andere kan bereyken’, waren in constante oorlog met elkaar. Conflicten werden grotendeels uitgevochten op zee, waarin de Molukse bevolking gebruik maakte van zogenaamde corcoras (Kora Kora). Deze traditionele kano’s komen ook voor in het bijbehorende kaartbeeld.

Ten tijde van de publicatie van de atlas (1664) had de Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) de Portugezen en Spanjaarden verdreven en een monopolie op de specerijenhandel weten te krijgen. Informatie over VOC-territoria, zoals de Molukken, was omstreden, omdat hiermee potentiële kennis werd vergeven aan de concurrenten. Belangrijk hierbij te vermelden is het feit dat Joan Blaeu de officiële kaartenmaker van de VOC was, en eigenlijk verplicht tot geheimhouding. Dat maakt de toevoeging van een kaart en beschrijving van de Molukken in de Grooten Atlas zeer opmerkelijk en biedt mogelijkheden tot verder onderzoek.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Storms, M. “Geheimhouding bij de VOC? De dubbele petten van Blaeu en van Keulen”, Caert Thresoor, 38 (1), pp. 14-25.

Turkije, door Gijs de Vries

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: NATOLIA QVÆ OLIM ASIA MINOR / Natolia, Eertijdts kleyn Asien

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 8110:2

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: TERRA SANCTA / Palæstina, ofte ‘t Landt Van Beloften

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 8150:2.2

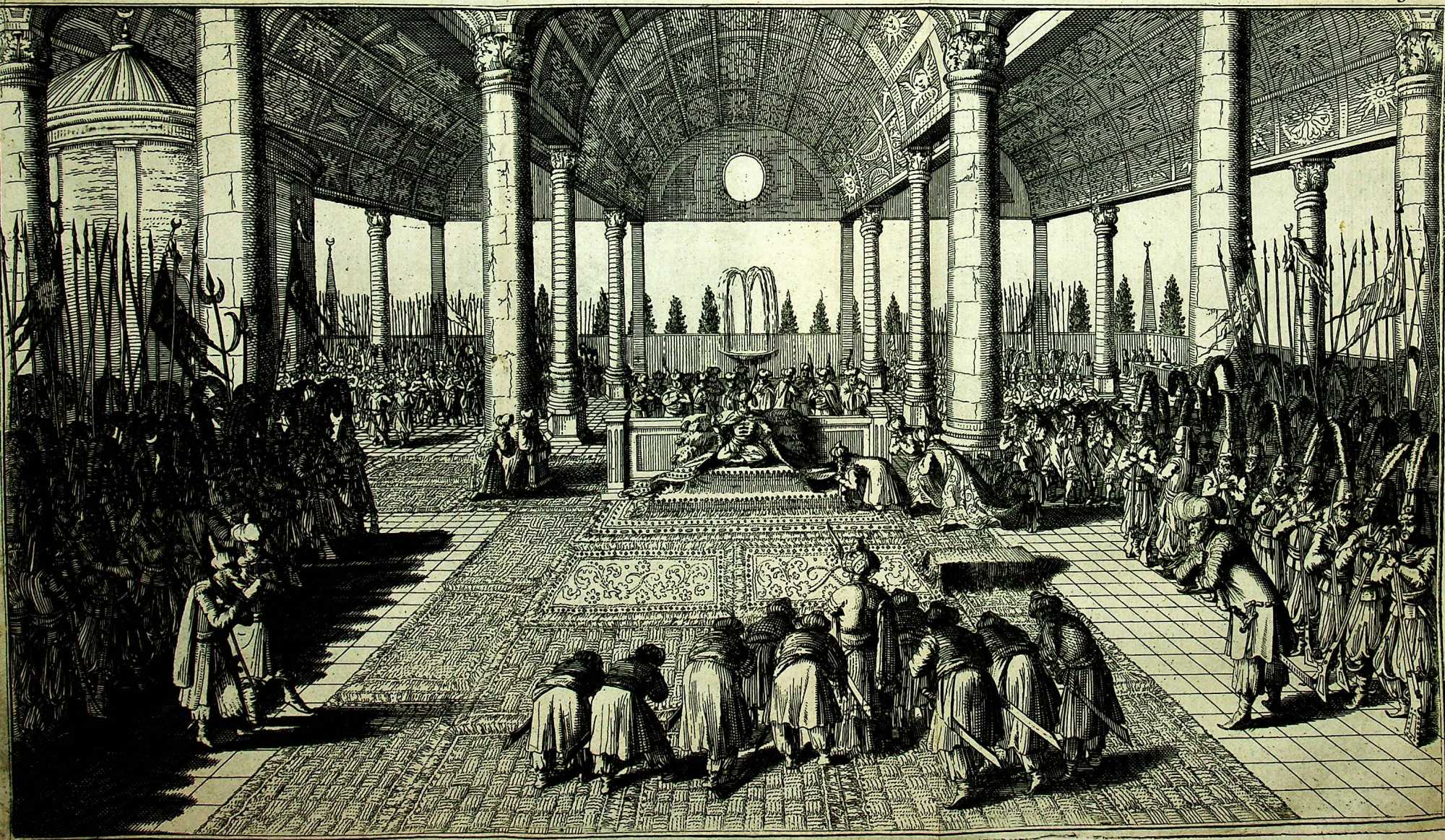

Het keizerrijk Turkije, ook wel bekend als het Ottomaanse Rijk, was een gebied dat meerdere regio’s besloeg en zich uitstrekte over de drie continenten Afrika, Azië en Europa. Twee van deze delen die door Blaeu in de Grooten Atlas specifiek worden benoemd zijn de regio’s Natolia en Palestina of het “Land van Belofte.” Natolia bestrijkt ongeveer het huidige Aziatische deel van Turkije en Palestina beslaat delen van Zuid-Libanon, Israël en de Palestijnse gebieden. Deze gebieden stonden in de tijd van Blaeu onder gezag van de eerdergenoemde Ottomanen of zoals ze destijds heetten: de “Turken”, wat echter ook een containerbegrip is dat in de vroegmoderne tijd standaard werd gebruikt voor moslims.

De religieuze focus in de regiobeschrijvingen van Turkije en Palestina voert duidelijk de boventoon. Zo heeft Blaeu het over ‘spottelijcke sotternyen’ als het gaat om het islamitische stichtingsverhaal. Ook rituelen en gebruiken die door hem als vreemd worden gezien, waaronder polygamie (het huwen van meerdere vrouwen door een man), beschrijft hij veroordelend. In het christelijke Europa was monogamie namelijk de norm.

Waar de religieuze aandacht in de beschrijving van het Ottomaanse Rijk vooral negatief en veroordelend is, vinden we in de religieuze passages over Palestina een sterke spirituele verwantschap met het gebied. Het zogeheten Heilige Land, of Beloofde Land, vormde immers de bakermat van het christendom. Blaeu beschrijft uitvoerig de plekken die verwijzen naar bijbelse verhalen, zoals de verwijzing naar de plaatsen Sodoma en Gammora, alsook de plek waar men stelt dat het Laatste Avondmaal (‘Paesch-lam’) werd genuttigd.

De focus op religie in de beschrijvingen van de Grooten Atlas van Blaeu en de achterliggende redenen voor deze focus zijn interessante aspecten die verder onderzoek rechtvaardigen.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Brummett, P. (2015). Mapping the Ottomans: Sovereignty, Territory, and Identity in the Early Modern Mediterranean . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Arabisch Schiereiland, door Timo Middelbos

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: ARABIA / Arabien

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 8180:2

‘Het is byna vierkant, en is meer dan een Half-eylant; want de zee bespoelt het aen drie sijden.’ Aldus de geografische omschrijving van het Arabisch schiereiland in de Grooten Atlas. In de zeventiende eeuw onderscheidde men drie gedeelten: Arabie Petrea, ’t Geluckige Arabie en ’t Woeste Arabie.

Het Gelukkige Arabië stond bekend om zijn rijkdom, handel en vruchtbaarheid. De Arabieren die aan de kust wonen, worden door Blaeu beschreven als van een ‘schoonder gestalte, en veel aangenamer dan d’ andere Arabiers.’ Daarnaast beweert Blaeu dat de kustbewoners een goed verstand hebben, voortreffelijk spreken en zich bezighouden met poëzie en de geneeskunde. Hieruit blijkt een zekere mate van respect en bewondering voor de culturele en intellectuele ontwikkelingen van het Gelukkige Arabië. Van respect of bewondering is echter geen sprake meer als we de passages over de andere gebieden doornemen. Zo blijkt Blaeu de bevolking van Arabië consistent denigrerend te beschrijven. Hij vermeldt dat de Arabieren in het algemeen ‘leelijck, mager, droogh en bruyn, als door de hitte gebrant’ zijn. Verder: ‘sy hebben een vrouwelijcke stem, en swarte oogen, met een fel en wreet gelaet.’

Het is natuurlijk interessant om te onderzoeken waar deze negatieve associaties vandaan komen. Daar zijn verschillende redenen voor te noemen. Enerzijds is er sprake van een nomadische cultuur die sterk afwijkt van de Europeanen die sedentair leven. Ook de kleding (‘schamel’) en de Arabische handelswijze (‘roofachtig’) werden veroordelend beschreven. Maar het is vooral in de religie dat het Arabische volk negatief wordt geassocieerd in de atlas van Blaeu. Die associatie gaat terug tot de Middeleeuwen, waarin de islam ontstaat en al snel in botsing komt met het christendom. Aanvankelijk in het Nabije Oosten, maar in de achtste en negende eeuw ook op het Iberisch schiereiland en zelfs tot in Frankrijk. In de tijd van Blaeu was het vooral de dreiging van de Ottomanen, in Centraal-Europa en op de Middellandse Zee, die bijdroeg aan een negatief beeld van het islamitisch geloof en iedereen die het beleed.

Zo kan deze schijnbaar ambivalente houding van Blaeu — het tegelijkertijd voorkomen van bewondering en afkeer — in zijn beschrijving van de Arabieren worden verklaard.

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Varthema, L. de, Jones, J. W., Badger, G.P. (1970). The travels of Ludovico di Varthema in Egypt, Syria, Arabia Deserta and Arabia Felix, in Persia, India and Ethiopia, a.d. 1503 to 1508 (Reproduction of the Works issued by the Hakluyt Society, 32). New York: Franklin.

Centraal-Azië, door Jeroen Bos

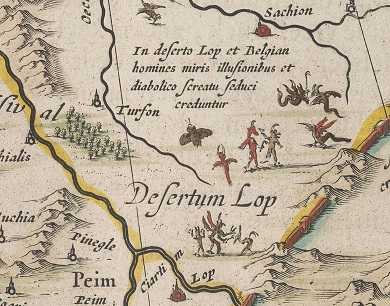

• Titel van de kaart / tekst: TARTARIA SIVE MAGNI CHAMI IMPERIVM / Tartarien Ofte Het Rijck van de Groote Cham

• Koeman, Atlantes Neerlandici, Vol. II, nr. 8050:2

Tartarije, of het Rijk van de Grote Cham, besloeg in de tijd van Blaeu grote delen van Centraal-Azië en strekte van Turkije tot aan Siberië en China. Duidelijk omkaderd was de regio geenszins. De verwijzing naar de grote khans van weleer, zoals Dzjengis (1162-1227) en Koeblai (1215-1294), doet al vermoeden dat er op oude bronnen wordt teruggevallen. Het zijn met name de Romein Plinius de Oudere (23-79) en de Venetiaanse reiziger en handelaar Marco Polo (1254-1324) op wie Blaeu leunde. Zo valt er op de kaart bij het fictieve eiland Tazata in de noordelijke ijszee te lezen dat dit eiland door Plinius wordt genoemd. Met uitzondering van het piepkleine ‘Staten Eylant’ linksboven in de kaart — door de Nederlanders vernoemd tijdens de laat-zestiende-eeuwse expedities om de Noord — verwijzen alle steden, streken, meren en rivieren op de kaart naar (verbasterde) namen die Polo noemt in zijn boek Il Milione (in het Nederlands vertaald als De wonderen van de Oriënt).

Plaatsnamen die Blaeu rechtstreeks overneemt uit Polo’s boek vormen bijvoorbeeld het ‘voortreffelijcke Paleys des Grooten Chams Cublai’, gelegen in Ganda, wat het huidige Shangdu (China) is. In de stad Quelinfu (het huidige Jian’ou, tevens in China) vond men volgens de Venetiaan zwarte kippen die ‘hayr als swarte katten’ hadden.

Hoe wonderlijk deze kippen ook mogen zijn, niets zorgt voor meer verwondering dan de ‘Bonaretz’ (ook: barometz), een fabelwezen dat half plant half dier was. Uit een plant groeide een schaapachtig wezen dat verbonden bleef met de plant. Het voedde zich met gras rondom de plant en als dat op was, stierf het dierlijke gedeelte van de bonaretz. Europese geleerden bleven tot in de negentiende eeuw naar dit fabelwezen zoeken en het opnemen in natuurhistorische publicaties. Toen werd het definitief als fabel bestempeld.

Fabelachtige wezens vinden we ook terug in het kaartbeeld. Zo zijn er bij de regio ‘Desertum Lop’ (een woestijn in de regio Xinjiang) allerlei demonische figuurtjes afgebeeld. Volgens Polo moesten reizende handelaren hier oppassen niet van een groep geïsoleerd te raken. Deze dwalende zielen zouden dan ten prooi vallen aan geesten en demonen, die zich in de woestijn ophielden.

Vraag blijft waarom Blaeu zich op Plinius en Polo baseerde. Was er geen actuelere informatie over de regio voorhanden? Die was er zeker, in gepubliceerde en ongepubliceerde vorm. Het was de Amsterdamse regent en schrijver Nicolaes Witsen (1641-1717) die alle beschikbare informatie over de regio actualiseerde in een veel nauwkeuriger kaart (1690) en het boek Noord en Oost Tartaryen (1705).

Suggestie om verder te lezen: Peters, M. (2010). ‘Mercator sapiens’ (de wijze koopman): het wereldwijde onderzoek van Nicolaes Witsen (1641-1717), burgemeester en VOC-bewindhebber van Amsterdam . Amsterdam: Bert Bakker