‘Narrated to Children’: Groningen's Relief from a 19th-Century Nationalistic Perspective

‘It happens all too often that the Groningen youth engage in all manner of revelry on the 28th of August, but without the joy of knowing, or the ability to recount, what the actual meaning of this celebration is.’

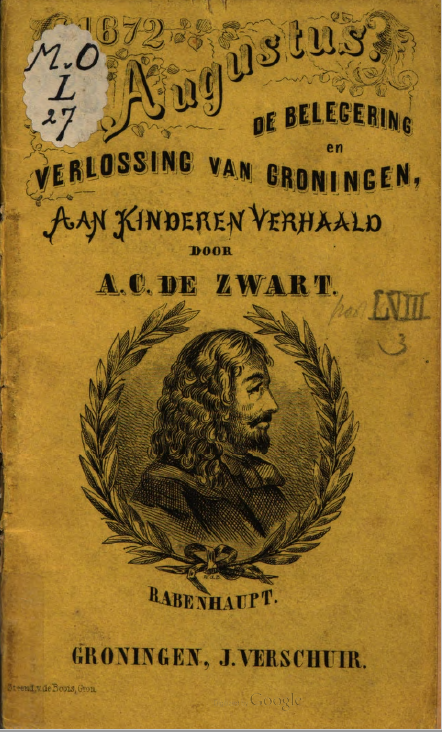

In these lines, the Groningen headmaster Aart Cornelis de Zwart (1836-1885) described quite precisely his reason for ‘dit feestgeschenkje te maken voor den 28sten Augustus’ (‘creating this celebration gift for the 28th of August’). In his opinion, the young people celebrated this day without even knowing what that they were celebrating; in other words, they lacked historical knowledge about the Rampjaar (‘Disaster Year’). And this knowledge is precisely what he wished to impart to them in his short collection, entitled 1672, 28 Augustus: de belegering en verlossing van Groningen, aan kinderen verhaald (‘1672, 28 August: the Siege and Redemption of Groningen, Narrated to Children’). In 28 pages, De Zwart chronologically recounted the events leading up to the Siege of Groningen and how the city bravely defended itself, causing Bernhard von Galen (‘Bombing Bernard’) to back down after barely one month. In doing so, De Zwart stressed the importance of history. But why did he place so much emphasis on knowledge of the past, and what does this tell us about the time when his book was published?

The ‘Disaster Year’ as a Source of Inspiration

Although the text concerns the ‘Disaster Year’, it says more about the time when it was written. The collection was published in the second half of the nineteenth century, known as the century of nationalism. This concept is quite controversial today, but in those days of nation and identity formation, nationalism and patriotism were very common.

In 1882, the French philosopher Ernest Renan defined a nation as the result of a common history and a common struggle. Solidarity was not created by country borders, but by a shared past involving collective sacrifices. The 19th-century perspective on the national past is therefore easy to explain. And what better way to evoke such feelings than by glorifying the past? Disasters, wars, and victories were used as a source of inspiration to evoke patriotism, and in this way, to strengthen national identity. This happened both in literature and poetry as well as in historiography.

‘Warm, Patriotic Feelings’ are Learnt at School

Nation formation and historiography went hand in hand, and the way history was taught changed under the influence of nationalism and other factors. Until the mid-nineteenth century, history had not been a compulsory school subject. It was only with the introduction of the Van de Brugghen Act in 1857 that every school pupil was offered history lessons. The reason for making this subject compulsory was the ‘opwekking van warme vaderlandsliefde als bestanddeel der nationale opvoeding’ (‘importance of arousing warm, patriotic feelings as part of national education’).

In this way, learning more about national history served a double objective: stimulating patriotism and ensuring that history would not be forgotten but instead retold by future generations. De Zwart also incorporated this idea in his text. He ends with these moralizing words: ‘Jeugdige lezers. Vergeet het niet en zegt het voort, goede burgers hebben hun vaderland lief boven alle landen der aarde’ (‘Young readers. Never forget this, and spread the word: good citizens love their fatherland above all countries on earth’). In that sense, Zwart’s text about the ‘Disaster Year’ is very much a product of its time.

‘How is it possible that our country still exists!’

How is this expressed in the text? And how did De Zwart make an event that occurred 200 years earlier interesting to children, especially if his goal was to arouse patriotic feelings? De Zwart used a number of tools, resulting in a text that mixes fact and fiction—something that was not unusual in historical writings of the time. For example, he peppers his factual chronology with references to an inclusive ‘us’. He talks about ‘ons vaderland’ (‘our fatherland’), ‘onzer schoone stad’ (‘our beautiful city’), ‘onze wallen’ (‘our ramparts’), ‘de dappere onzen’ (‘our braves’) facing the ‘moorddadige vijand’ (‘murderous enemy’) bent on ‘ons te vernietigen’ (‘destroying us’). The implicit message is: pay attention, this is also about you.

Another tool used by De Zwart is the numerous examples of sacrifices made by Groningen citizens in their struggle against Bishop Von Galen. He speaks of the houses around the Herepoort and the Oosterpoort being demolished so that the enemy would not be able to use them. The inhabitants sacrificed their home for the greater good, because ‘in den oorlog en bij eene belegering vraagt men niet naar het belang van één of twee personen; men denkt maar: wat zal voor het behoud van onzer stad het beste wezen?’ (‘in times of war and siege, you do not ask about the interests of one or two individuals; instead, you ask: how can we best preserve our city?’). An admirable act, according to De Zwart.

Women’s arms being shot off, heads and arms being crushed, a cannonball hitting a peasant before blowing a potter’s child right out of its mother’s arms. Details abound. De Zwart even named the streets in which the victims fell. In this way, he brought history close to the present day: this is our common past, it is that which connects us. He also remained close to the experience of his young audience: ‘Men verhaalt ook nog van een jongen, die, uit school komende, eene bom zag neervallen, en eer die gesprongen was, spoedig de brandende lont met modder stopte, zoodat er geene verwoesting aangerigt werd. Dat was een dappere jongen, niet waar?’ (‘They also tell the story of a boy coming home from school, who saw a bomb fall, and before it had a chance to detonate, quickly extinguished the burning wick with mud, thus preventing more destruction. That was one courageous boy, don’t you think?’).

This headmaster used history as camouflage for his contemporary patriotic message.

Sources

- De Zwart, Aart Cornelis. 1672, 28 Augustus: de belegering en verlossing van Groningen, aan kinderen verhaald. Groningen: J. Verschuir, 1875.

- Buijnsters, P. J. and L. Buijnsters-Smets. Lust en leering. Geschiedenis van het Nederlandse kinderboek in de negentiende eeuw. Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, 2001.

- Jensen, L.. De verheerlijking van het verleden. Helden, literatuur en natievorming in de negentiende eeuw. Nijmegen: Uitgeverij Vantilt, 2008.

- Van Raamsdonk, Wouter. ‘Bommenberend voor schooljongens verklaard’. Groniek, 172, (2006): 355-367.

- Renan, Ernest. ‘What is a nation? (Qu’est-ce qu’une nation?, 1882).’ In What is a Nation? And other Political Writings. Edited by M.F.N. Giglioli, 247-263. New York: Columbia Univer-sity Press, 2018.

- Toebes, J. G. ‘Van een leervak naar een denk -en doevak. Een bijdrage tot de geschiedenis van het Nederlands geschiedenisonderwijs.’ Kleio: tijdschrift van de vereniging van geschiedenis leraren in Nederland 17, 3 (1976): 202-245.