University and Society in the 1930s

The growing number of students in Groningen is a hot topic. Out of every six people living in town, one is a student. During the KEI-week especially, inhabitants of the city experience a lot of nuisance from students. But is this a new phenomenon? Back in the 1930s, people were having lively discussions about the growing number of students and the university’s role in society. This becomes apparent when looking through the archive of Harm Tewes Deelman, which is kept at the Special Collections department of the Groningen University Library. This archive consists of a binder full of documents belonging to the commissie ter bestudering van het vraagstuk der overbevolking van universiteiten en hogescholen, a committee meant to advice the government on the problem of student overcrowding. Nearly a hundred years on, the issue is still relevant.

The committee, led by Mr. J. Limburg, researched the feasibility of the growing number of highly educated people in the Netherlands between 1933 and 1936. In 1900, there were roughly 2800 students in the Netherlands, by 1930 there were more than twelve thousand, whilst the economy was in recession. This growth can be attributed to new admission rules.[1] The quick increase in the student population caused the government to worry about academic overcrowding: ‘Nothing is as demoralizing as intellectual unemployment and it is known that this demoralization casts a dark shadow across the mindset of the entire population’.[2]

At the time, universities were facing a big change in their educational model. In 1931, Prof. H.R. Kruyt wrote a rave review of American universities in his brochure Hooge School en Maatschappij. In 1927, he traveled to the United States and visited several universities. His takeaway from the experience was that American universities ‘prepared their students to become leaders in all elements of society,’ while Dutch universities ‘failed to meet the needs of an evolving society.’[3] Dutch people also looked to the universities to give the right example during a time of moral degeneration. All in all, the universities had to adapt in order to survive.

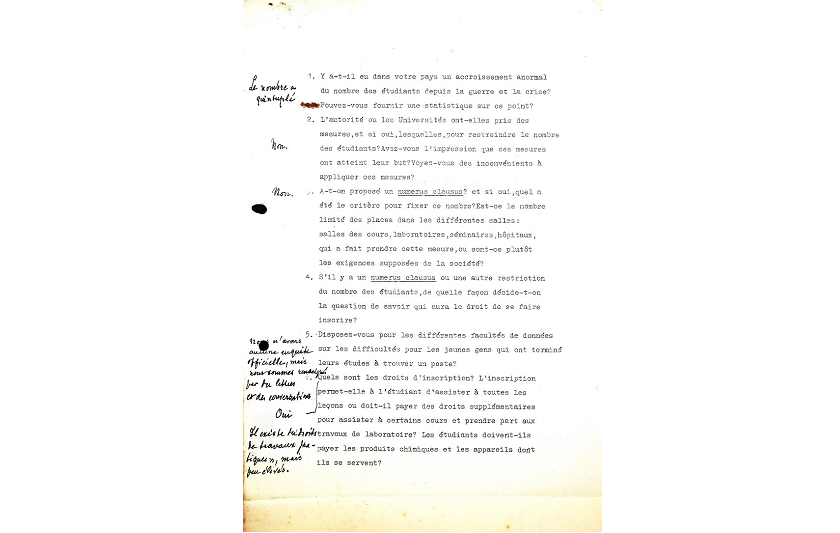

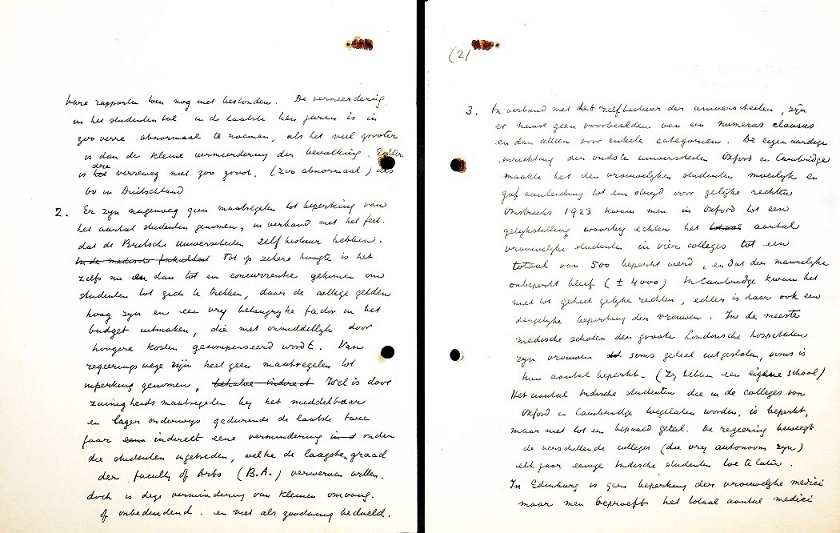

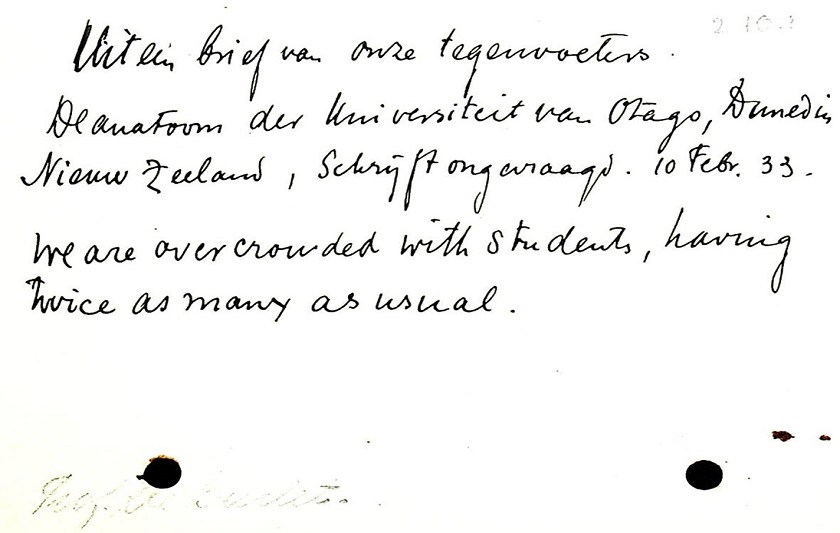

One of the committee members was Dr. H.J. Reinink, an economist from Groningen who was also a board member of the University of Groningen at the time. His main responsibility as a committee member was to organize a survey for academics across the Western world. This survey would be used to assess whether universities abroad were facing the same issues as Dutch universities and to assess whether any measures had been taken against student overcrowding. Reinink enlisted his University of Groningen colleagues to help him distribute the survey by sending it to acquaintances in their field. Earlier, the survey had been sent to Dutch embassies, but this proved to be an ineffective distribution strategy.

The archive of Harm Tewes Deelman is a wonderful example of data gathering in an analog society. In the back of the binder, I found a stack of notes with messages such as ‘With this message you’ll find the survey for distribution’ and ‘With this message you’ll find a response I’ve received.’ Gathering information on this scale involved a lot of administration. Unfortunately, there is no known data about the number of surveys distributed, or whether the archive is a complete overview of the responses. It is clear that some respondents had more to say than others. Someone at the University of Lille wrote one-word answers in the margins of the survey, while a ten-page reply from Edinburgh enthusiastically chronicles the situation across the United Kingdom. Although Reinink and his colleagues worked hard on the project, it was mostly in vain. The surveys did not make it into the committee’s final report, nor did any data about the situation abroad extracted from these surveys.

The committee’s final report did contain eleven recommendations, many of which have been realized over the years. An example of this would be the introduction of an internship as part of the study program. The proposed entrance exam ‘to test the candidate’s suitably for higher education’[4] is now called study matching. Other measures include limiting the number of resits to two for each subject, as well as a binding study advice. The committee concludes that a legal limitation on the maximum number of students should only be applied in a worst-case scenario. The responsibility to manage student overcrowding should be with the universities themselves, not with the government.

You could say the committee was rather progressive. The problems noted by the committee are relevant to this day and many of their proposed solutions have been implemented, although those solutions created problems in their turn. Many of them have been (or will be) abolished because of their unintended negative consequences. Despite their progressive takes, I think the committee members would be very surprised if they visited the university today. The academy is bursting at the seams. You could call it student overpopulation, but nowadays it tends to get framed as a teacher and personnel shortage, as well as a lack of resources for properly educating all of these students.

The accessibility of the university has increased enormously over the years. The motivations people have for studying have changed. No longer do we study only to maintain or improve our social standing; people also study to satisfy their curiosity and hunger for knowledge, to develop themselves, and, above all, to have fun. The committee, which looked at the needs of society rather than those of the individual, would never have accepted this: ‘The committee cannot see any positives in unlimited access to higher education, neither for the individual, nor for society.’[5] The questions that are being asked may not have changed, but the times certainly have.

Notes

-

Van Berkel, K. ‘Amerikanisering van de Nederlandse Universiteit?’, Tijdschrift voor de Geschiedenis der Geneeskunde, Natuurwetenschappen, Wiskunde en Techniek 12, 1989, p. 222.

-

Limburg, J. De Toekomst Der Academisch Gegradueerden: Rapport Van De Commissie Ter Bestudeering Van De Toenemende Bevolking Van Universiteiten En Hoogescholen En De Werkgelegenheid Voor Academisch Gevormden. Groningen: Wolters, 1936, p. 4.

-

Kruyt, H.R. Hooge School en Maatschappij. Amsterdam: H.J. Paris, 1931, p. 8, 11.

-

Limburg, J. De Toekomst Der Academisch Gegradueerden, p. 601.

-

Limburg, J. De Toekomst Der Academisch Gegradueerden, p. 576.