Christianity and Culture: A Czech Honorary Doctorate for Gerardus van der Leeuw

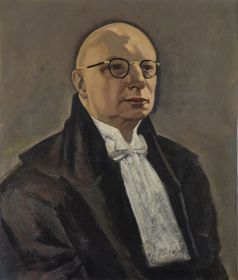

In the 1950s, Dutch theological faculties became the stage for a lively debate between modern and more traditional religious scholars. The discussion centered on the tension between biblical exegesis and church tradition on one side, and the study of religion as a sociological or psychological phenomenon—open to comparison with non-Western religions—on the other. Gerardus van der Leeuw was a key figure in the latter approach. In 1918, at just 28 years old, he became a professor in the history of religions, Egyptology, and the phenomenology of religion at the University of Groningen.

Though he passed away in 1950, many of his students and colleagues continued to regard him as a foundational influence on the development of religious studies in the Netherlands.

Recently, two biographies were published about prominent students of Van der Leeuw—Jannes Reiling and Fokke Sierksma—which explore the profound impact their mentor had on their spiritual lives. Biographer Jelle Horjus notes that Van der Leeuw had an “electrifying effect” on his assistant Jannes Reiling, who later became the leader of the Union of Baptist Churches in the Netherlands. In the eyes of Reiling and Sierksma, Van der Leeuw represented an “ethical” direction in theology: a progressive outlook that embraced the religious experiences of diverse faiths, ecumenism, and a keen interest in politics, society, art, and culture. Van der Leeuw taught that everything was infused with divine power and presence.

Van der Leeuw’s lectures attracted students from beyond the theological faculty. Charismatic and engaging, he often stepped outside the confines of academia. During his lectures, he could captivate his audience with compelling stories and humor, but above all, he wanted students to experience their faith. It wasn’t uncommon for him to break into a Negro spiritual or sing a Bach aria in the middle of a lecture.

Our archives contain several boxes of Van der Leeuw’s notes, prepared for the many lectures he delivered at home and abroad. He consistently explored the relationship between individual religious experience—phenomenology, so to say—and the cultural community from which the believer emerged. In preparation for a lecture in Brussels on January 15, 1932, he wrote:

“Culture is a grand and often misused, but indispensable word. ‘Civilization’ doesn’t suffice. Even uncivilized people have culture. One can have civilization or not, just as people can be or not. (...) Culture is our life, our glory, our power. He has been given all power. No one can serve two masters. There is no struggle between religion and culture, but an immense struggle between I and God, between our power and His power. A struggle that can only end in one way: bowing, kneeling.”

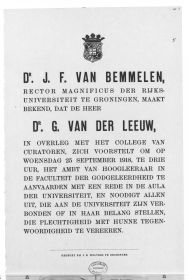

To analyze religion as a cultural phenomenon, Van der Leeuw believed researchers needed to relate the individual’s experience of the divine to their own understanding—a method he called “verstehende psychologie” (understanding psychology). His letters to his children during the postwar years illustrate how this approach worked in practice. In November 1946, he traveled to Masaryk University in Brno, then part of Czechoslovakia, where he was awarded an honorary doctorate in philosophy by Rector Josef Ludvík Fischer. Fischer, who had fled to the Netherlands during World War II, was, according to Van der Leeuw, a “remarkable man, a dynamic personality.”

In his letters, Van der Leeuw described lively discussions with students and colleagues, conducted in English, French, and German. He sought to understand how people in Czech society, so soon after the war, experienced life, religion, and art. After receiving the honorary degree, he wrote to his children: “Well, well! Yesterday was quite a day! In the morning, visits to the rector and the dean of the philosophy faculty. (...) Then the ceremony. A packed hall, lots of spotlights. Magnificent fanfare, choral singing. The entrance of the rector’s beadle with the rector, the faculty’s beadle with the dean.” All the pomp soon became overwhelming for Van der Leeuw. Fortunately, after the ceremony, there was time for “beer in a café. Life here revolves around the cafés.”

The day after the ceremony, Van der Leeuw traveled with Fischer to Prague, where, at the invitation of Justice Minister Prokop Drtina, he attended a performance of Antonín Dvořák’s opera Jakobin. Van der Leeuw was so impressed by Drtina’s hospitality that, upon returning to the Netherlands, he published two travel letters on “Politics and Culture in Czechoslovakia” in the weekly magazine De Groene. He described having an “animated conversation about politics” with the minister, “followed by an even more animated conversation about opera. A country where even the Minister of Justice is a passionate opera lover must be truly civilized.”

In his travel letters, Van der Leeuw noted that the Czechs were “only lukewarm in their religiosity”: “Generally, one can say that the spirit of Hus, Comenius, and Masaryk has left deep marks, and a practical humanism prevails in their spiritual attitude.” Yet, the warmth with which the theologian engaged his Czech interlocutors must have been infectious. It is doubtful whether he realized that the opportunity to understand Czech culture from within would soon be severely restricted. After the communist takeover in February 1948, Czechoslovakia was largely cut off from the outside world. Just a year earlier, Van der Leeuw had concluded that the country’s “nationally grounded, democratically oriented, and highly purposeful cultural policy” could serve as an example for the Netherlands: “We cannot imitate the Czechs, but we could certainly learn a thing or two from them.” In hindsight, this conclusion seems both poignant and ominous.