Mapping Empire: Decoding Blaeu’s Vision of India

Introduction

There’s something undeniably captivating about old maps. Worn edges, elaborate compass roses, sea monsters adrift in unknown waters. These images don’t just chart the world, they narrate it. Cartography, especially in the early modern period, was as much about imagination and ideology as it was about politics and geography.

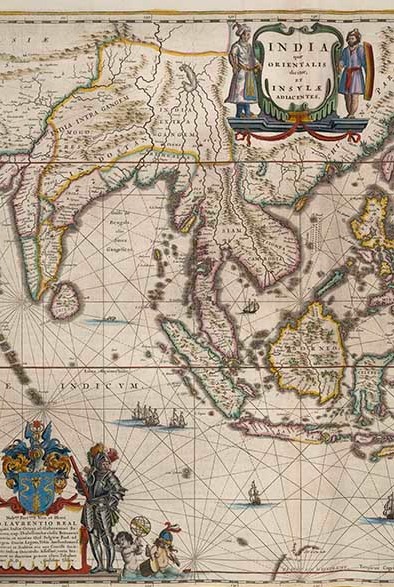

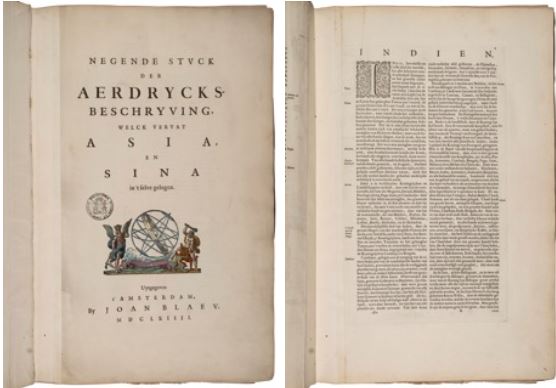

Originally drafted by Willem Blaeu for the Atlas Novus and later expanded upon by his son Joan Blaeu in the monumental Atlas Maior, the map depicting India is a particularly intriguing example of early modern cartography. First published in Latin in 1662 and translated into Dutch by 1664, the ninth volume of the Atlas Maior features India prominently in the top left corner of the map titled “East India and the Adjacent Islands”. This exhibition delves into the rich visual language of the map— its illustrations, decorative elements, and geographic markers that offer a revealing glimpse into the Eurocentric worldviews of the seventeenth century. Alongside these visual elements, this exhibition explores and translates the accompanying texts on India, which further illuminate how European cartographers like Blaeu interpreted and represented distant lands through a colonial and often imaginative lens.

Among the most influential mapmakers of this age was the Blaeu family, a Dutch dynasty of cartographers whose work defined the visual language of the Dutch Golden Age and Empire. Under the stewardship of Joan Blaeu, the family’s atlas production reached canonical heights. As chief cartographer to the Dutch East India Company (VOC), Joan Blaeu held a unique position at the intersection of commerce, science, and empire. His maps were not only tools for navigation but also powerful representations of Dutch ambition and curiosity in a rapidly expanding world.

This exhibition, “Mapping Empire: Decoding Blaeu’s Vision of India”, examines one such creation— a map of India that blends intricate artistry with layered narratives. More than a geographical record, Blaeu’s depiction offers a rare window into how Europe imagined and interpreted the Indian subcontinent in the early days of colonial contact. Combining visual spectacle with descriptive travelogues, the map embodies both the fascination with and the misunderstandings of India that characterised European knowledge production at the time. By decoding its symbols, inscriptions, and contexts, we trace how cartography functioned not only as a science but as a cultural document; one that reveals as much about its makers as it does about the lands it seeks to represent.

Why This Map Matters

The Blaeu map of India stands out as one of the few surviving visual records of the Indian subcontinent’s political and cultural landscape at the dawn of European and Mughal colonisation. At a time when the Mughal Empire held control over much of northern India and the Portuguese had already established coastal strongholds on the southern coasts, this map offers a rare snapshot of the subcontinent before British imperial dominance was cemented. It captures a moment in which Indian empires were still powerful entities, depicted through the eyes of early modern Europe, however, its accuracy remains uncertain due to a lack of comparable sources that have remained intact from the time.

The scarcity of comparable visual records from the same period is what sets this Blaeu map apart. Its uniqueness stems from the rarity of authentic cartographic depictions of pre-colonial Indian empires ruled by Indian dynasties, making it an invaluable and singular resource for understanding the geopolitical landscape of the era.

What makes this map particularly compelling is its historical lens. As a European interpretation of a complex, diverse, and often misunderstood geopolitical landscape, it tells us as much about European ambitions and imaginations as it does about India itself. The map’s rendering of boundaries, cities, and routes is shaped by limited information, hearsay, and colonial narratives, offering insight into how early modern Europeans viewed the East—not as it was, but as it was useful or desirable to depict. In this way, the map is both a document of India and a mirror of Europe’s own priorities and ambitions of expanding the Empire.

Beyond its immediate visual appeal, the map is part of a much larger cartographic legacy. Created during the Dutch Golden Age, it was embedded in Joan Blaeu’s grand vision to visually assert global knowledge and dominance through mapmaking. As chief cartographer for the Dutch East India Company, Blaeu’s work was as political as it was geographic. Maps like this one were not only tools of navigation, but also instruments of empire, power, and social prestige. By charting lands far beyond Europe, Blaeu helped construct a worldview where Europe stood at the center, surrounded by territories to be known, claimed, and controlled.

In short, this map matters because it encapsulates a key historical moment when cartography, empire, and imagination converged.

Reading the Map: Banners

The map, “East India and the Adjacent Islands” measures 390 x 500 mm, and was created in 1635 for Willem Blaeu’s Atlas Novus. It was later included in Joan Blaeu’s Atlas Maior.

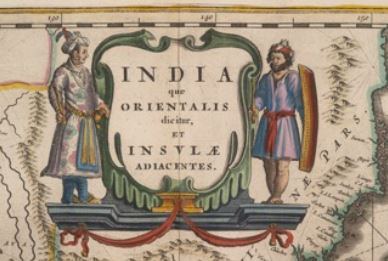

The top banner of the map features two striking male figures dressed in local textiles, highlighting European fascination with the opulence and resources of the East. According to the accompanying text on India, their garments are most likely crafted from silk, cotton and indigo. The figure on the left is presumed to be a royal, possibly a mughal emperor, as suggested by his luxurious headgear adorned with pearls and feathers. He is decorated with jewelry, gold jootis (traditional footwear), and a sword. His floral silk attire is rendered with such skill that the illustrator manages to capture the subtle sheen of the fabric. In contrast, the figure on the right, likely a soldier, barefoot and bare-legged, is wielding a sword and shield. His beard and attire create a stark visual distinction between ruler and guard, luxury and labour, suggesting both social hierarchy and Eastern power structures.

In the bottom left corner of the map, a Latin dedication honors Laurens Reale, a prominent Dutch statesman and former Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies.

The inscription reads: “To the most noble, valiant and heroic man Mr. Laurence Real, Knight, once supreme governor of East India, recently vicarius vice-regent of the British fleet ruling the waves, and on behalf of the States of the United Netherlands, ambassador to the King of Denmark, senator and “schepen” of the city of Amsterdam, as well as assessor board member in the Chamber of the East India Company, famous in various genres of literature and learning, Willem Blaeu donated this map.” This dedication acknowledges Reael’s political and maritime stature, and also reflects the close ties between cartography, statecraft, and ambitions of the Dutch Republic during its Golden Age. The dedication to Reael, a close friend of Willem Blaeu, is believed to have played a key role in helping Blaeu acquire copper plates from VOC directors.

On the left of the dedication, the Greek goddess Athena is illustrated wearing white, green, gold, with feathers adorning her helmet, holding a shield emblazoned with the head of Medusa. As the goddess of wisdom and war, her presence is suggestive of the Empire’s aspirations for knowledge and control. On the right, stands a European figure in silver armour, holding a red scroll. His commanding stance and prominent placement suggest he represents Reael. At his feet, two cupid-like children are shown handling cartographic instruments as an allegorical nod to exploration and the dissemination of geographical knowledge.

Visual and Symbolic Design

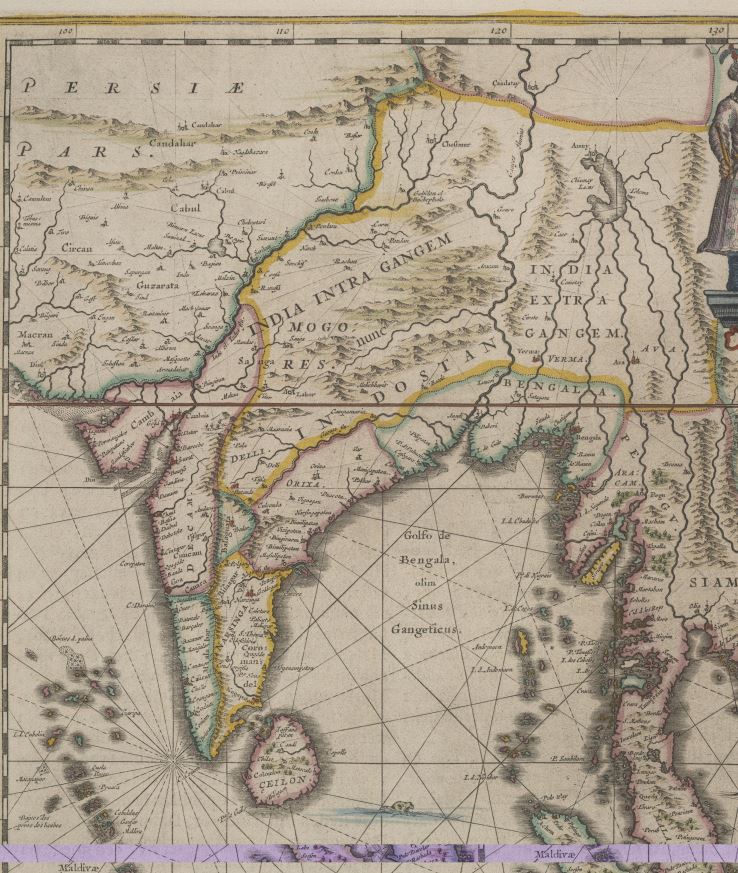

Joan Blaeu’s 17th-century map of India stands out for its vivid use of colour and symbolic geography. Bright shades such as pinks, blues, yellows, help demarcate political boundaries, with yellow marking “Indostan,” the Mughal Empire, annotated as “Mogo Res Nunc” (Mughal rule currently). The empire is further divided into “India intra/extra Gangem” – inside and outside the Ganges; a classical distinction drawn from older European cartographic traditions.

Small red fortresses scattered across the map indicate areas under local Indian rule, accompanied by the names of dynasties such as Ava, Narsinga, and Verma. These markers show a fragmented political landscape, distinguishing regions like Cambaia and Decam (modern Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra), Indostan (covering much of northern India, including parts of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh), Bengal, Odisha (spelled Orixa), Balaguata (the central highlands), Narsinga and the Coromandel Coast (Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh), and the Malabar Coast (Karnataka and Kerala).

A large red dot marks the Indian state of Goa, presumably to emphasise what was considered the “chief city” of India. This symbol may serve a dual purpose. Firstly, as a city marker, and possibly as a visual motif for estuarine river openings, a convention seen in other contemporary European cartography. However, this interpretation is speculative, and the exact intent behind such symbols remains open to question.

What distinguishes this map is its intricate attention to Indian rulers and regional empires, something often overlooked in European maps of the time. Rivers, mountain ranges, and coastal lines are also carefully drawn, though not always geographically accurate. These features serve more as symbolic boundaries, showing an imaginative blend of real geography with speculative illustrations.

Blaeu and his contemporaries sourced such information from European merchants, missionaries, and travelers who had firsthand access to the subcontinent. Their maps often acted as visual companions to the travelogues of the time, displaying clear intertextuality. Blaeu’s map, for example, borrows language and visual motifs directly from The Voyages of Jan Huygen van Linschoten, a widely circulated travel narrative.

In sum, Blaeu’s map is as much a political and cultural document as a geographic one. It layers colonial interpretations with local realities, and showcases how early modern European knowledge of India was shaped through a mix of observation, imagination, and textual borrowing.

Blaeu’s Atlas and Textual Epistemologies

The image of India presented to European readers in Blaeu’s atlas was one of grandeur, abundance, and exotic richness, constructed through both text and map, and often filtered through earlier travelogues such as those by Jan Huygen van Linschoten. India is described as “the noblest and best part of the world,” bordered by the Indus River and Arabian Sea in the west, the Taurus mountains in the north, the great eastern sea, and the Indian Ocean to the south. The land is divided by the Ganges into two regions, India beyond the Ganges to the east, and Indostan to the west, each rich in population, cities, and natural abundance.

The accompanying text emphasises India’s fertility and wealth, claiming it offers an unmatched variety of spices, fragrant gums, jewels, pearls, silks and other textiles, as goods it supposedly distributes generously to the rest of the world. This portrayal also includes detailed references to its political and economic geography, such as the mention of 47 kingdoms and Goa as the principal hub of trade, under the supervision of the Portuguese Viceroy and Archbishop. Much of this information was derived secondhand, often from travelers’ accounts rather than direct experience.

Passages from Linschoten’s writings appear almost verbatim in the atlas, revealing Blaeu’s reliance on earlier European sources in constructing his vision of India. These textual echoes highlight how knowledge was copied and repurposed across genres and authors. However, there remains a notable dissonance between these romanticised descriptions and the lived realities of Indian people. The atlas at times reflects Eurocentric misreadings and appropriations, criticising local customs, clothing, and religious practices, often reinforcing a colonial, fetishised and orientalised gaze that shaped how India was perceived rather than accurately represented.

The Chief City of 17th Century India: Goa

The state of Goa holds symbolic importance in the European reading of India. Interpreted both visually and textually, Goa is not only depicted in the body of the Indian map but also prominently illustrated on the decorative border of the map of Asia, in the same volume. Its urban layout and bustling ports are carefully rendered, showcasing a city marked by Portuguese colonial influence.

The red-tiled buildings, fortifications, and shipping activity reflect Goa as the religious capital and trading hub. Its strategic location on the western coast, bordered by fertile landscapes and open sea, underline its significance as the administrative seat of Portuguese India. It is where the Viceroy of India resided and the Archbishop held authority, making it a centre of European control in the East.

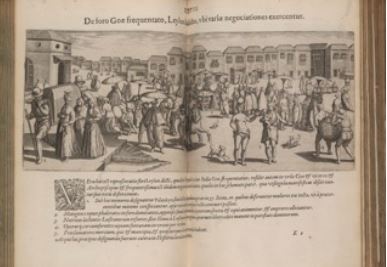

Goa’s prominence in the Atlas Maior symbolises the height of colonial ambition, framed as a gateway to the resources of the East. As a microcosm of European imperial aspirations, Goa also embodied cultural hybridity. Linschoten’s detailed account in his Itinerario, captures this hybridity through rich ethnographic descriptions of Goa’s social and cultural life.

Linschoten observed the land and its people with a mixture of curiosity and judgment. His writings describe the bustling local markets selling everything from fine textiles and spices to slaves and services. The city gates were manned by guards, and within them, diverse communities coexisted including Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Jews, and the growing population of mestiços, children of Portuguese and Indian unions. Linschoten categorised people by race, class, and occupation, noting their titles, rules of the Viceroy, anecdotes about dynasties and local rulers. His accounts included details about family life, local customs, and gendered rituals, such as women bathing in water perfumed with herbs and roses, wearing elaborate clothing, and adhering to class-based codes of conduct.

Religious diversity in Goa was a theme that both fascinated and unsettled Linschoten. He wrote about the peaceful coexistence of multiple faiths, but often contrasted Indian customs with those of the Dutch, framing certain traditions as exotic or less civil. Eating habits and clothing became markers of Otherness. These cultural observations were not neutral, but filtered through a lens that both admired and aimed to dominate what it saw.

The natural landscape also contributed to Goa’s allure. Agriculture, domesticated animals, fruit trees, and detailed depictions of money exchange and ports reinforced its image as a land of wealth and productivity. In both image and text, Goa emerges as the “chief city” of India and as an emblem of conquest, commerce, and cross-cultural contact. Yet the lens through which it was portrayed reveals as much about European worldviews as it does about the realities of Indian society.

Decolonising the Archive

Blaeu’s map of India and the accompanying texts are more than a geographic document. It is a cultural artifact shaped by the ambitions and ideologies of colonial Europe. While it visually charts land, cities, mountain ranges, rivers and ports, it also encodes a worldview that sought to frame India through the means of European authority. Maps like Blaeu’s were not neutral tools of exploration; they were instruments of both discovery and domination, aiming to establish knowledge as a form of power.

This representation was deeply influenced by earlier European narratives, particularly those found in travel accounts like Jan Huygen van Linschoten’s Itinerario. These texts informed the atlas’s content and tone, shaping how Indian people, landscapes, and cultures were understood or misunderstood by European audiences. Through selective descriptions, cultural comparisons, and emphasis on commercial potential, these narratives helped justify and sustain colonial attitudes. They reinforced the idea of India as a place to be observed, categorised, and eventually controlled as a centre of European power away from the West.

Understanding these sources is crucial for decolonising historical archives. Reinterpreting such materials allows us to question whose perspectives were viewed, what realities were omitted, and how knowledge was disseminated. Engaging critically with texts and maps is not just an academic exercise; it is a step toward reclaiming historical agency and recognising the complexity of the cultures that were represented through foreign eyes.

In this light, Blaeu’s map becomes a reflection of early European encounters with India— encounters marked by fascination and sometimes misinterpretation. It reveals as much about Europe’s imagination and intentions as it does about India itself. Revisiting these materials offers a valuable window into the processes of cultural framing and historical narrative-building. It challenges us to think about how identities were shaped by cartographic and textual authority, and how they continue to influence our understanding of history today.

By reading Blaeu’s atlas not just as a document of geography but as a tool of empire, we gain deeper insight into the entangled histories of Europe and India and the power of representation in shaping both past and present.

| Last modified: | 20 May 2025 11.25 a.m. |