Bibliotheca Italiana at the UB

While many students may enjoy the occasional taste of Italian culture, little do they know that The Netherlands is one of the 84 countries hosting branches - comitati - of the Società Dante Alighieri, with a committee right here in the city of Groningen.

The Società Dante Alighieri

On May 11, 1899, a group of intellectuals led by Giosuè Carducci founded La Società Dante Alighieri, with the aim to ‘protect and spread the Italian language and culture across the world, strenghtening the ties of compatriots abroad with the mother country and nurturing love and admiration for the Italian civilisation among foreigners’. Given the historical period in which La Dante was founded, the main mission of the society was twofold. Firstly, it wanted to check on the migrants' health and boarding conditions. Secondly, its aim was to provide migrating Italians with a small library that teachers could use to educate illiterate compatriots during the journey at sea. With this idea in mind, movable libraries were instituted. By 1920-21, the society comprised of 200 committees within Italy and its former colonies, and 93 outside the country.

Between 1903 and 1932 Paolo Boselli was president of La Dante. During these years profound changes were put into motion. After Benito Mussolini visited the headquarters in 1924, a royal decree assigned Palazzo Firenze in Rome as the site for La Dante in 1926. In 1932, Giovanni Celesia di Vegliasco was nominated president of the society by the fascist government. The government took full hold of the Società during the infamous year 1938. Jewish associates and collaborators were expelled via private correspondence sent out to the presidents of the various committees throughout the country. Mussolini used the society as an instrument for his Italianist propaganda, instating statutes in 1931 that obliged the society to interpret Italianità (=Italianity) as a synonym of fascism. In 1938, he also tried to destroy the foreign branches of La Dante under the control of the Italian embassies. While he did not succeed, the fascist period harmed the reputation of the institution as an independent organisation, as its founders had always advocated political and religious freedom up until then.

Following the liberation in 1944, young members of La Dante came up with a manifesto, marking the rebirth of the society after the war. In 1945, a new democratic statute declared that:

La Società Dante Alighieri, founded in 1889, aims to protect and disseminate the Italian language and culture in the world, independently from any political view, race, nationality, confession or ideology. This independent association belongs to those who are united by the love for the Italian language, which is connected to humanism and the universal language of music, and who are morally inspired by the high model of the Dantesque character.

This statute was approved by the decree of the president of the Republic in 1949. The 1950s were also the period in which foreigners started to show interest in La Dante and the Italian language in general. Nowadays, the scope of the Società Dante Alighieri remains the same. In 1994, the diplomat Bruno Bottai, son of Giuseppe Bottai - the founder and director of the fascist magazine Critica Fascista - became president of the society. He remained in charge until 2014.

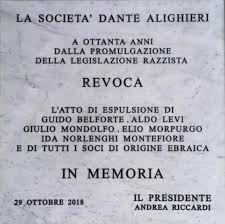

Revoking the Jewish expulsion

This revocation, performed by Andrea Riccardi as president of La Dante, arrived 80 years after the promulgation of the Italian Racial Laws of 1938. Many thought this action came too late. Nothing had been done before to annul or apologise for the expulsion. A headstone, set in Piazza Firenze, Rome, commemorates the revocation of the expulsion of the circa 500 Jewish members of La Dante. The unveiling ceremony coincided with a conference and a campaign against antisemitism organised by La Dante named La cultura italiana, la Società Dante Alighieri e l'antisemitismo italiano. Amongst the people present at the uncovering of the headstone were Andrea Riccardi, the president at the time, the Chief Rabbi, Riccardo di Segni, and the president of the Jewish Community in Rome, Ruth Dureghello. The relatives of the expelled 500 members also attended the conference and received a diploma assigning them perpetual membership to the Società Dante Alighieri.

Società Dante Alighieri in The Netherlands

Despite the fact that the Netherlands was never a important destination for Italian immigrants, local branches of the Società emerged thanks to the personal efforts of Romano Guarnieri (1893-1955). He went on to study Romance languages at the University of Groningen. He was appointed in 1926 as a special lecturer of Italian at the University of Amsterdam, and in 1934 as a special professor of Italian at the University of Utrecht.

Guarnieri is considered a highly controversial person. From its early origins during the 1920s, he openly supported fascism and praised Mussolini’s ideals in Italian as well as Dutch newspapers and magazines. In 1927, Mussolini even appointed Guarnieri as acting consul of Italy in the Netherlands. His support for the fascist regime took a very dark turn in his life when Mussolini adopted the anti-semitic laws of Nazi Germany, followed by the German occupation of the Netherlands in 1940. This marked Guarnieri’s first break with fascism as his wife, Carla Simons, was Jewish, and Guarnieri never supported any form of antisemitism. In 1943, Carla was arrested along with many other Jews. Using his connections, Guarnieri tried to have his wife released, for which he, rather ironically, used his reputation as an ardent supporter of the fascist regime. This could not save Carla from the fate that many Dutch Jews suffered, as she was deported a few months later to Auschwitz, where she died. Following the end of WWII, Guarnieri was acquitted by the academic committee that had to judge whether he had been a collaborator during the war. He was reinstated as professor, despite the fact that many people still distrusted him due to his past allegiance to the Fascist Party, which he had denounced. After his retirement in 1952, Guarnieri returned to Italy, where he died following a tragic accident with a cyclist in 1955. Yet, despite his controversial history and tragic life, Guarnieri was of great importance to the study of Italian language and culture in the Netherlands, and La Dante would not have existed without his efforts.

Local chapters of La Dante were founded across the country between 1934 and 1939. Members from La Dante in the Netherlands are almost exclusively Dutch. During Mussolini's dictatorship, and as a result of the changed role of the society, some committees ceased their activities as a form of protest and only resumed after the Second World War.

La Dante Groningen

Committees of La Dante are found in many major cities across the Netherlands. The chapter in Groningen was founded on December 1, 1924. The Groningen Committee of La Dante is celebrating, as of 2024, its 100th year since its installation.

In 1924, Giovanni di Casamichela, the professor of Italian language and literature at the University of Groningen, initiated correspondence with the headquarters of La Dante because he was interested in founding a comitato in the city. Alongside administrative matters, he requested books for the establishment of a social library and financial assistance to promote the initiative and increase the number of members. The Committee was established at the end of the year, on December 1st and was named the Committee of Northern Holland, as it extended to the neighbouring provinces of Friesland and Drenthe. The first board of the Committee was only provisional and had prof. di Casamichela as its president. The provisional headquarters was at Maesstraat 16. The official elections for the board were held on February 3, 1925, appointing prof. A.G. Roos as president and prof. di Casamichela as secretary.

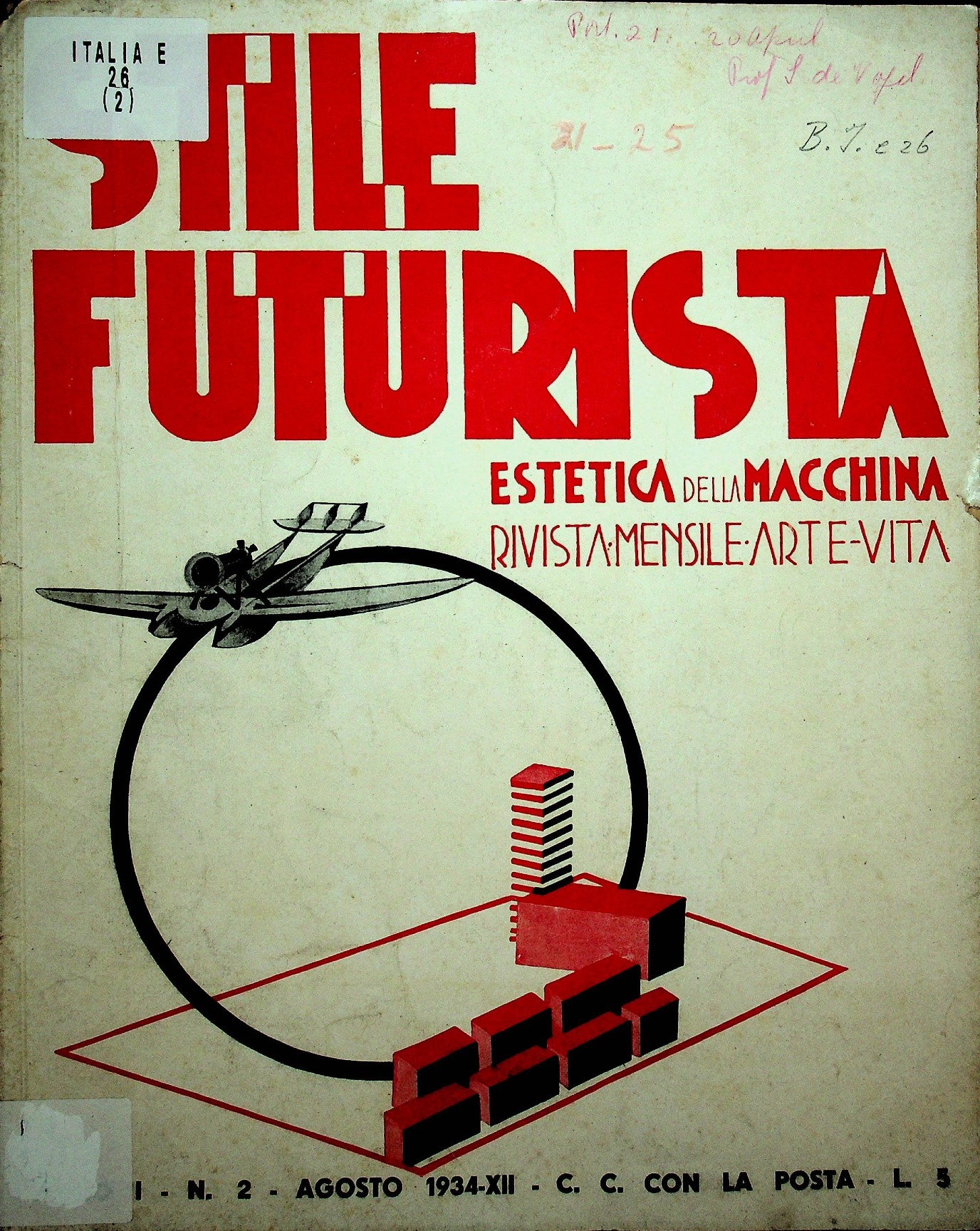

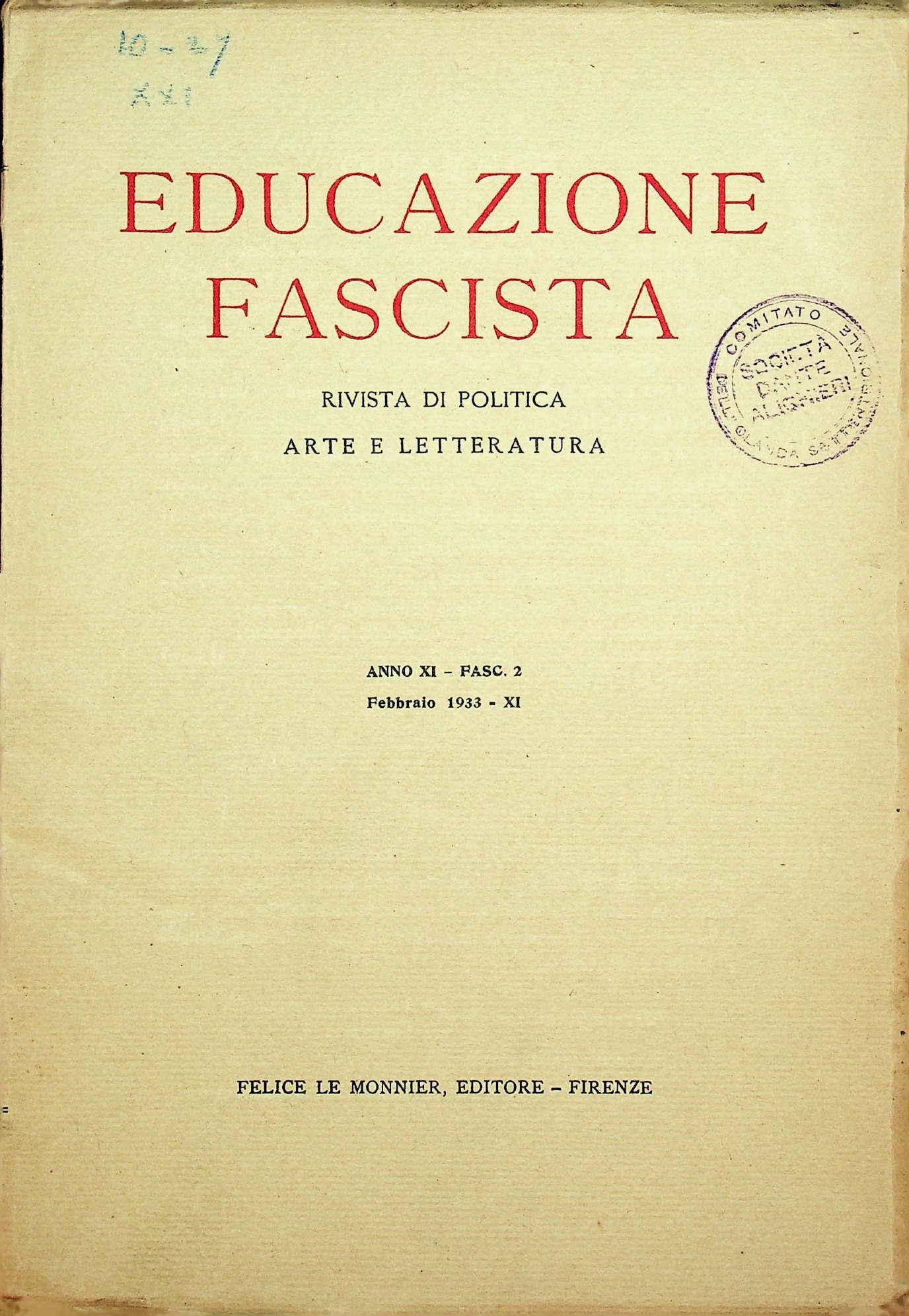

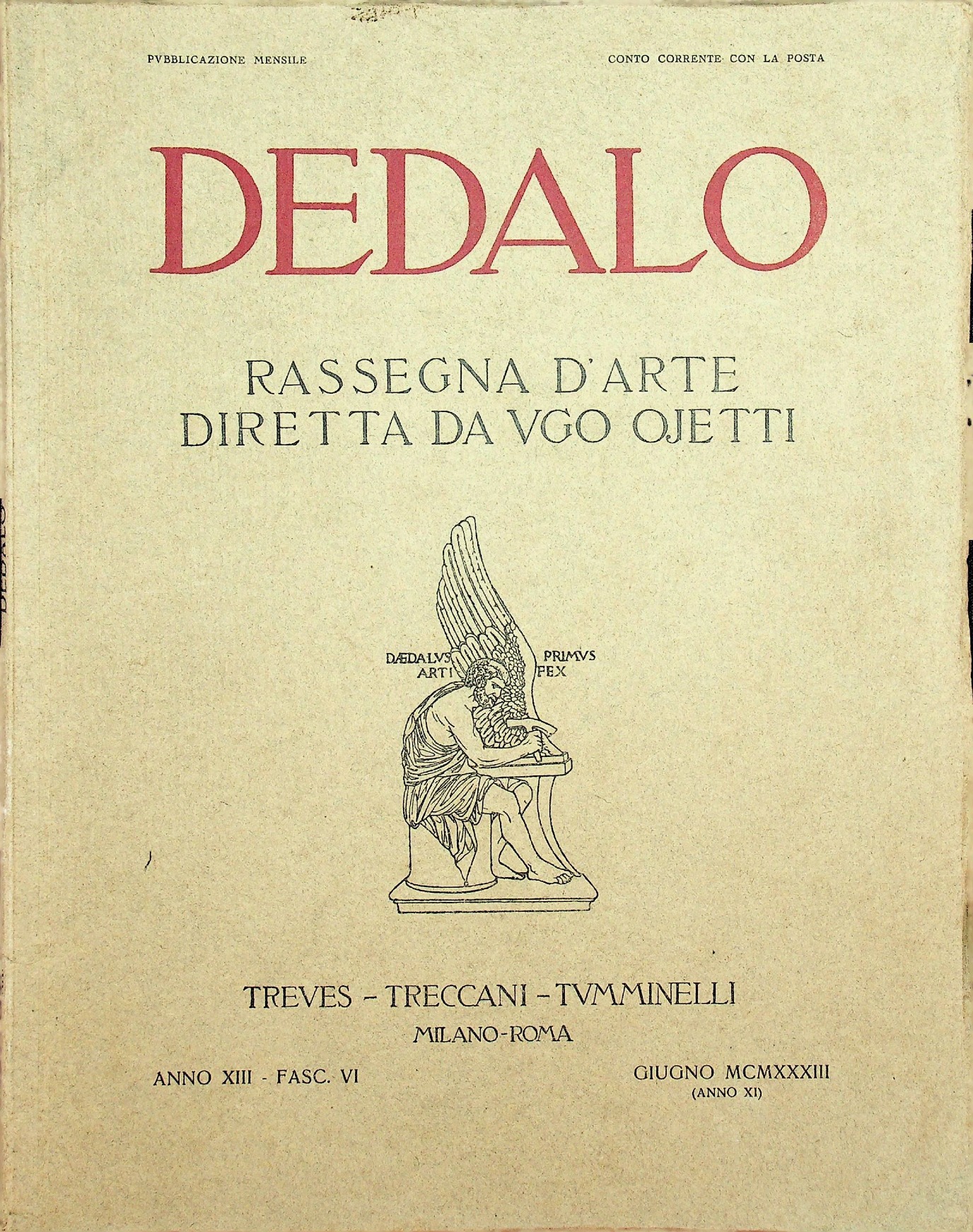

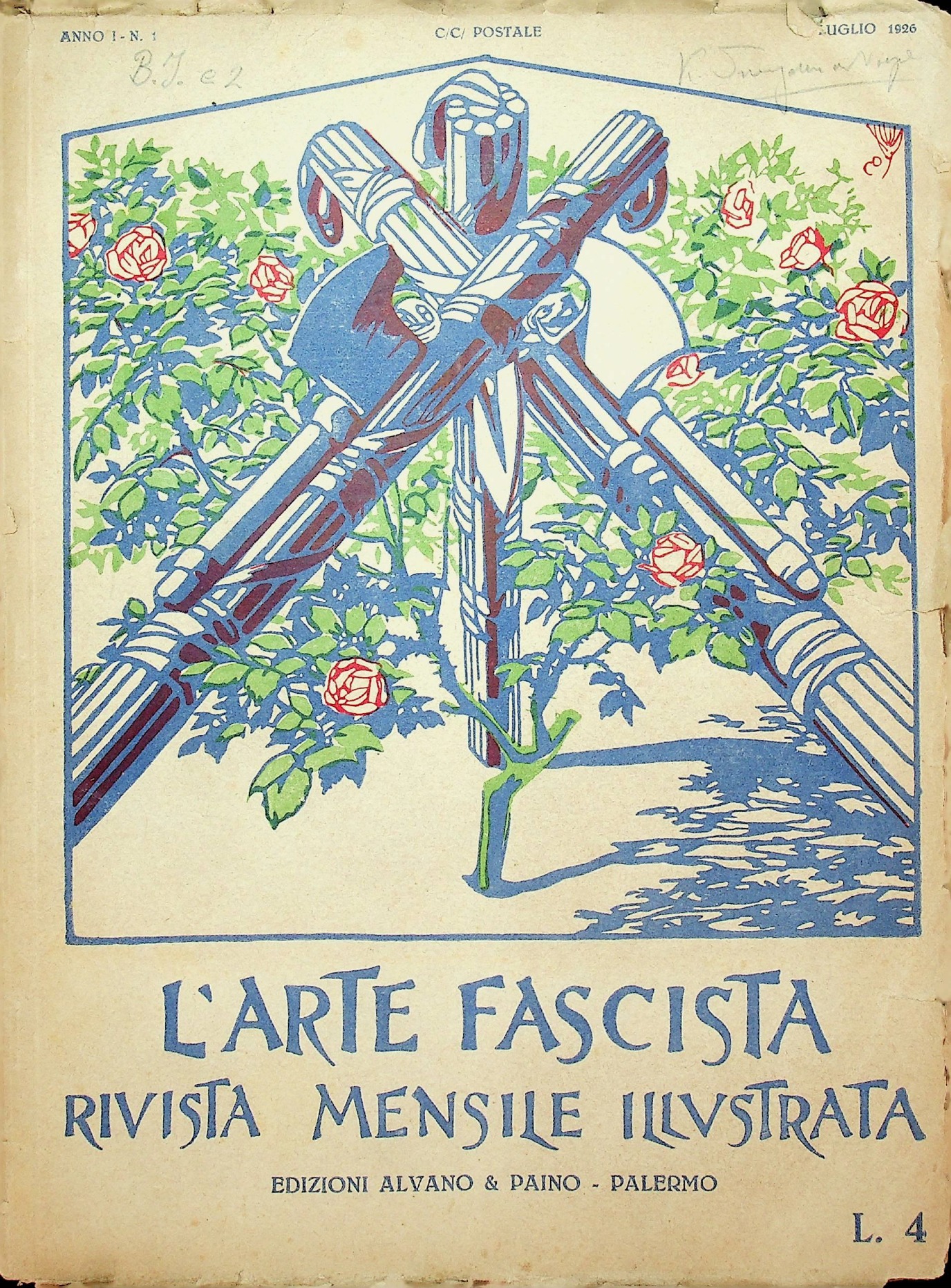

Since its foundation, the Groningen Committee has been interested in receiving books for its library. From correspondence, it is known that prof. Giovanni di Casamichela donated some personal ones. Starting in 1931, the Roman Headquarters of La Dante gave the Groningen Committee a subscription to various cultural and political magazines. In January 1933, the Central Office sent a copy of La Vita di Arnaldo written by Benito Mussolini, In 1934, the headquarters made available to the Committee the magazine Critica Fascista by Giuseppe Bottai, amongst others. In September 1934, another 30 volumes were sent to the Committee, and in March 1935, Dr Augusto Garcia, a lecturer in Italian language and literature at the University of Groningen, donated 40 books. In 1937, subscriptions to monthly periodicals were renewed.

In October 1940, due to the war circumstances and economic reasons, the number of committee members decreased from 24 to 8, therefore the three remaining members of the Board of Directors decided to suspend the Committee's activities and leave the library in deposit at the University of Groningen Library, ensuring its public use. In March 1941, the suspension of all activities was officially ratified. It might also be that the Istituto Italiano di Cultura, which also has a site in Amsterdam, asked multiple committees, including the one in Groningen, to close as a response to the fascist turn La Dante had taken.

In 1946, President Roos resumed contacts with the headquarters for the reconstitution of the Committee, which took place in January 1947. The Roman headquarters granted new magazine subscriptions and sent 4 packages of books. Magazine subscriptions renewed again in 1949 and 1950.

There is no information on whether the collection was moved from the University Library to a different location by the time the Groningen Committee was reinstated. This might be because of inconsistencies in archival upkeeping of the Committee. Chapters of La Dante outside of Italy often do not have a permanent site, and, amongst other reasons, the members are hosted usually by the president, while archival documentation resides privately with the secretary. However, a special catalogue was published in 1930 with an annex from 1950 -available only in the Italian language-, while the University Library dates in its journals -journalen- the first lease from La Dante in 1961.

In 1991, the collection specialist Jelle Kingma published Kunst, cultuur en politiek in Italië 1920-1940, a collection of studies -available only in Dutch- on the influence of Italian Art and culture in the northern provinces of the Netherlands, which coincided with an exhibition held at the Library on the subject.

Currently, the Groningen Comitato is composed of circa forty Dutch members, who all share a great love for Italy. They meet regularly for small conferences on the Italian language and culture, while Valerio Cugia, the only Groningen member of Italian origin, hosts a literary salon at his house.

All things considered, La Dante Groningen together with the Bibliotheca Italiana is a unique testimony of Italian culture and 20th century fascism in the north of the Netherlands.

While it tells us something about the history of the Società Dante Alighieri in Groningen. Nevertheless, the Bibliotheca Italiana remains an interesting collection for anyone interested in fascist art, politics and culture, and literature in the Italian twentieth century.

The Bibliotheca Italiana in Groningen

Since 1961, the UB has hosted a collection of Italian books loaned by the Groningen Committee of the Società Dante Alighieri in its basement. It contains approximately 900 books and a substantial collection of magazines and anthologies, particularly from the Italian fascist period. Through this unique collection of fascist magazines, bibliographic and critical journals, political writings, and periodicals, we can clearly witness how fascist ideology shaped the cultural climate in Italy in the 1920s and 30s.

Benito Mussolini

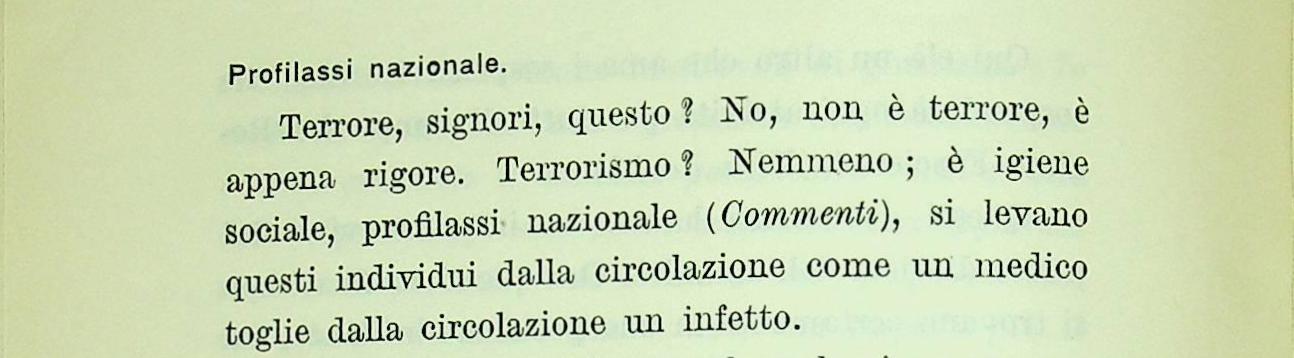

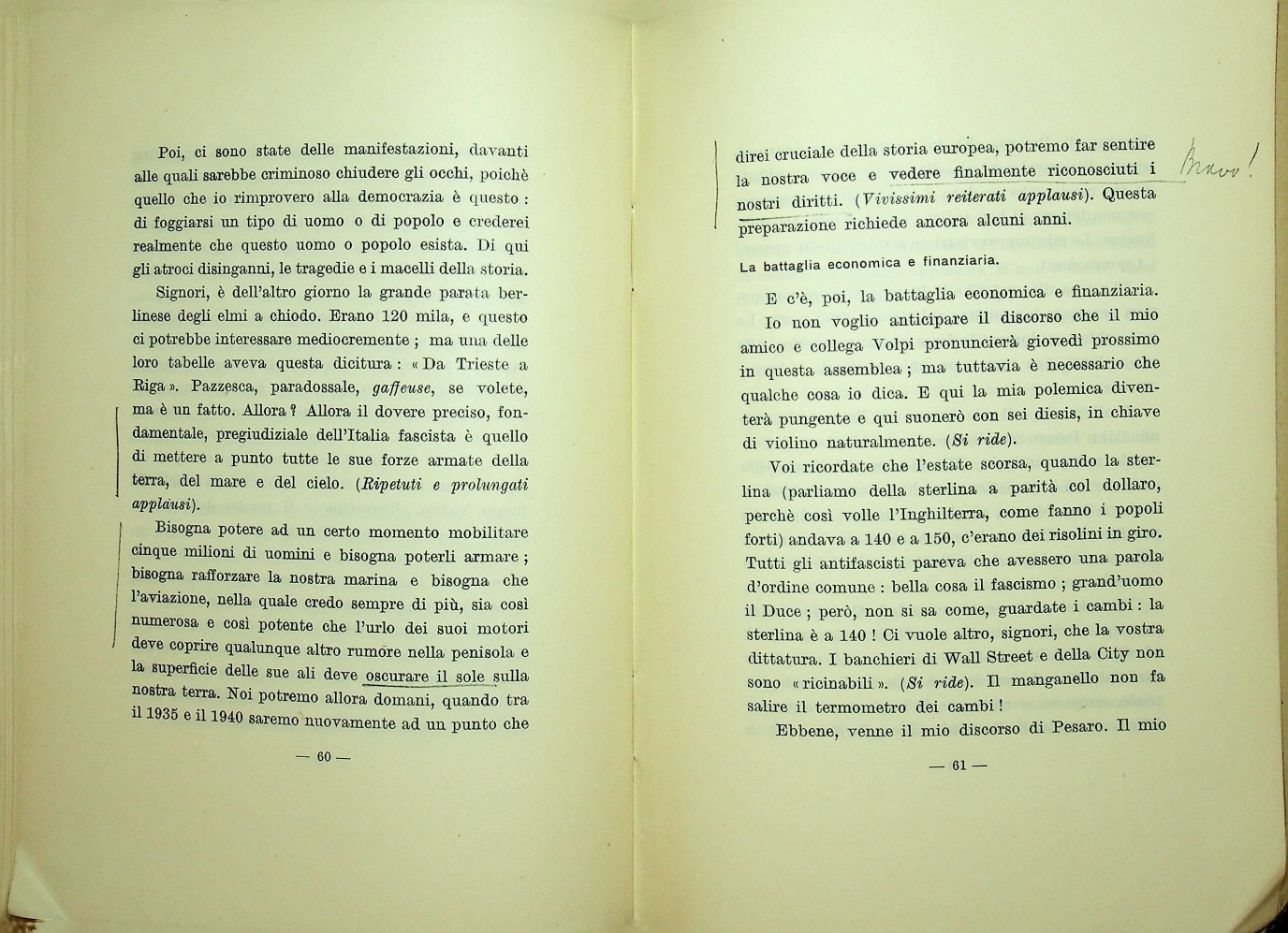

In the Library’s strong room in the Special Collections Department, Benito Mussolini’s La Nazione di Fronte a Se Stessa is preserved, a published version of the speech of the Ascension (It: dell’Ascensione), called this way because Mussolini held this cardinal speech for the Regime as the new Head of government on Ascension day (May 26, 1927).

In this speech, Mussolini covered topics from birth rate and maternity to the ‘defense of the race’, the fight against anti-fascism, and the ‘grandiosity of Italy’. With this speech, he aimed to incite Italians to join the fray for Italy to become an empire.

Mussolini’s ambitions are amply laid out in this speech. He aimed to not only create a new type of Italian man -l’italiano guerriero (the Italian warrior)- but also raise the Italian nation to an empire. To achieve this, he needed a demographic increase, controlling family nuclei, and imposing standards on motherhood. In Mussolini’s view, families had to be numerous and women were meant to be compliant bearers of children and caregivers. Men who would not comply with conjugal sexual activities, or even opposed marriage, were considered deserters.

To defend the ‘race’ of the fascist Italian warrior, Mussolini needed to get rid of those he believed inapt for his regime and the political opposition, which he saw as a cancer to extirpate - needless, and dangerous:

An interesting aspect of this publication is that it is the only one I have encountered in my research to have annotations in the margins. While the identity of the original owner is unknown, these annotations enable us to speculate on his political stand as a supporter of Mussolini’s fascism:

Fascist Periodicals

The Bibliotheca Italiana of the University Library offers a collection of periodicals and magazines from the fascist period. The following are those founded -and closed down- during the Regime.