The evolution of animal personalities

In recent years evidence has been accumulating that personalities are not only found in humans but also in a wide range of other animal species. Individuals differ consistently in their behavioural tendencies and the behaviour in one context is often correlated with the behaviour in multiple other contexts. From an adaptive point of view, the existence of such personalities is puzzling in several respects. First, why do different personality types stably coexist? Second, why is behaviour not more flexible but correlated across contexts and through time? And third, why are the same type of traits correlated in very different taxa?

We developed a series of conceptual evolutionary models to address these questions. With these models we aimed to address behavioural aspects of personalities that appear to have some universality (i.e., occur in a range of animal species). At present, there seem to be at least two candidates that suite this condition: the boldness-aggression syndrome and individual differences in responsiveness.

Many ../../indexers would probably agree that the boldness-aggression syndrome is one of most reported findings in the animal personality literature. In a nutshell, individuals within the same population differ consistently in their aggressiveness towards intruders and these differences are positively correlated with differences in boldness in response to predators and activity levels in unfamiliar environments.

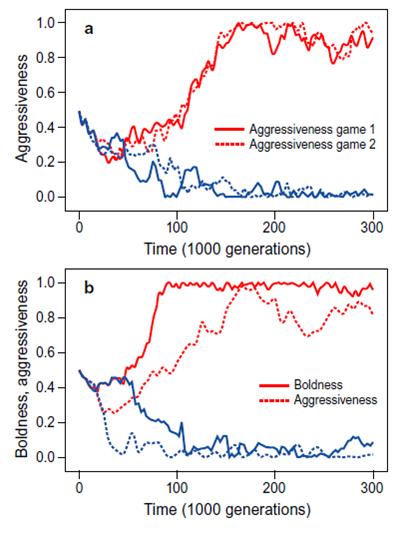

We developed an evolutionary model (Fig 8) that showed how these observations can be explained in terms of a basic principle from life-history theory, the principle of asset protection. According to this principle, individuals with high future expectations should be more risk-averse than individuals with low expectations, since they have more to lose. In a first step we showed that the common trade-off between current and future reproduction often results in polymorphic populations where some individuals put more emphasis on future fitness returns than others. We then showed that the asset protection principle can explain differences in suites of correlated behavioural traits that are consistent over time: individuals with high expectations evolve consistently risk prone behaviour in a variety of behavioural contexts (high levels of aggressiveness and boldness) whereas low expectation individuals evolve consistently risk averse behaviour.

Empirical studies in a range of animal species suggest that individuals within populations often differ along a responsiveness (reactivity, flexibility, awareness) axis: at the unresponsive end of this spectrum we find individuals with an intrinsic behavioural control that quickly develop routines and show relatively rigid behaviour; at the responsive end we find individuals with a more extrinsic control of behaviour that remain reactive to environmental stimuli and show flexible behaviour. While it is easy to see that the optimal degree of responsiveness depends on features of the environment such as the degree of environmental variation, the presence of cues and sampling costs, it is not obvious why individuals that face the exact same environment should differ in their responsiveness.

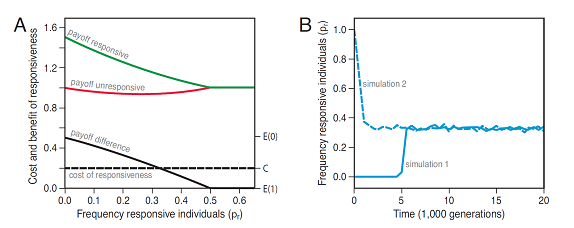

We developed an evolutionary model (Fig 9) that showed that both spatial and temporal variation in the environment can give rise to adaptive individual differences in responsiveness. We focussed on the common scenario where the payoffs at the level of the behavioural choices are negatively frequency dependent (e.g., choice between a risky and a safe patch, choice between an aggressive hawk and a non-aggressive dove strategy): the more individuals that choose one of the behavioural options, the lower the payoff that is associated with this option.

In a first step we showed that this basic scenario gives rise to benefits of responsiveness that are negatively frequency dependent. The intuition for this result goes as follows: responsive individuals exploit environmental opportunities (e.g., switch to the more profitable patch). The benefits that are associated with these opportunities, however, will decrease with the frequency of individuals in the population that exploit these opportunities and thus with the frequency of responsive individuals in the population. Benefits of responsiveness that are negative frequency-dependent, in turn, favour the coexistence of responsive and unresponsive individuals. In short, responsive individuals are favoured because they can exploit opportunities in their environment. Unresponsive individuals can exploit the fact that responsive individuals tend to homogenize the environment and thus the payoffs associated with behavioural alternatives.

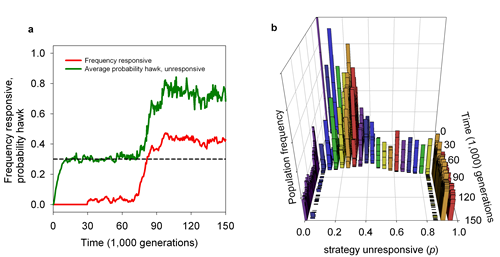

While behavioural consistency over time is one of the hallmarks of personalities, its adaptive value is not yet well understood. Current explanations focus on constraints in the architecture of behaviour (e.g., pleiotropic genes) and positive feedback mechanisms such as learning and training. We developed a model (Fig 10) to investigate a third explanation, namely that consistency is favoured since it makes individuals predictable.

Predictability, however, can only be advantageous if at least some individuals in the population respond in an adaptive way to individual differences. Consequently, the evolution of consistency and responsiveness are mutually dependent. We developed an evolutionary model that investigates this coevolutionary feedback. We first showed that responsive strategies are favoured whenever some individual differences are present in the population (e.g., due to mutation and drift). We then showed that the presence of responsive individuals can trigger a coevolutionary process between responsiveness and consistency that gives rise to populations in which responsive individuals coexist with unresponsive individuals that show high levels of adaptive consistency in their behaviour. Next to providing an adaptive explanation for behavioural consistency our results thus also link two key features associated with animal personalities, individual differences in responsiveness and behavioural consistency.