Christianity and the History of Ideas Archive

Below you will find a description of our previous PhD research that took place.

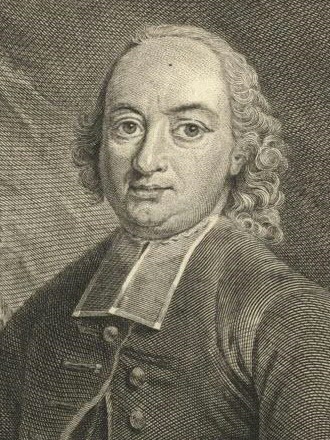

Johann Friedrich Stapfer (1708-1775): Reformed Orthodoxy and Theological Rationalism

Born and bred into a famous family of pastors, Johann Friedrich Stapfer, a Swiss pastor from Brugg, spent all his life asking three simple questions: “how do we distinguish between truth and error?” ; “what are the foundations of true religion?” ; and, “How should we live?” By the end of his life, he had dealt with these questions in a staggering 25 volumes written in Latin and German and translated into Dutch. He was a representative of

Reformed theology in the phase of Later Orthodoxy (1700-1775) abandoned the old classical synthesis between eclectic Aristotelianism and Reformed theology, supplanting it with a new synthesis with either the Cartesianism of Saumer, or the Leibniz-Wolffian philosophy. Meanwhile, during the Enlightenment many streams of philosophy of religion produced thinkers and schools of thought that one really ought to characterize as “rationalist theology.”

In the eighteenth century, many considered Stapfer one of the foremost European theologians, and as such, he had influence on Jonathan Edwards, Immanuel Kant, Bernhardus de Moor, Archibald Alexander, and a whole generation of Dutch Reformed ministers and theologians. Stapfer’s 1742 dissertation on Naturalism later formed the largest part of his first published book in five volumes, Institutiones theologiae polemicae universae (Zurich, 1743-47). In Stapfer's view Naturalism was the most powerful weapon of unbelief. Noticing the central place Stapfer afforded to Naturalism, we will investigate it as a case study of rationalism.

This study proceeds on the bias that theology finds its expression within a philosophical mould, which functions as presuppositions. The question under consideration here is whether the Leibniz-Wolff synthesis experiment was a good idea for Reformed thought, both theologically and apologetically. With these considerations in mind, we study Stapfer to answer the big questions in a small way by simply asking, “What is the relationship between Reformed orthodoxy and theological rationalism?”

Corné Blaauw

Currently I am working on my doctoral thesis which focuses on the role of (power-sharing) democracy in peace operations and is concerned with the place of (religious) collective identities within democracy in post-conflict societies. Case studies that are of importance for this project are for example Northern Ireland and, especially, Bosnia-Herzegovina.

My research interests lie in social and political philosophy as well as in International Relations, and particularly concern peace and peacebuilding, democracy, and social ontology.

Good refugee, bad refugee: The political and cultural implications of the current 'refugee crisis' and the construction of the 'Other' in the Netherlands and in Australia

The recent arrival of thousands of refugees in Europe and the high number of people dying during the journey has created public and political polarization within host populations, and between (member) states. This new and massive migration and the high number of deaths demand immediate action for the European Union and its member states to act, not only in terms of providing humanitarian aid and saving people at sea, and basic human needs such as housing, but also providing for a long term solution as well. Political and cultural institutions had and still have to find ways of dealing with these large groups of people in terms of legal and safe avenues to access protection in the European Union. Yet, even in the face of this pressing need, some EU leaders seem determined to insist on exclusionary and hostile positions and continue to employ harsh rhetoric. Interestingly, a similar isolationist, exclusionary position has informed Australia’s public and political response to ‘boat arrivals’ on Australian shores since the first boats arrived in 1976 in the aftermath of the Vietnam War.

The focus of this project is not to ‘compare and contrast’ Europe and Australia as such, but to identify and critically examine the common language of fear, exclusion and hostility that is increasingly reflected in public and political discourses accompanying the migration crises in both Europe and Australia. Up until this point, despite the recognition of these exclusionary discourses, relatively little attention has been paid in either European or Australian context, or a parallel context combining both, to the ways in which, if any, these discourses have been accompanied and informed by dichotomies on religion, Islam and refugees.

The project aims to identify and examine how the binary oppositions of ‘good religion/bad religion’, ‘good Muslim/bad Muslim’, and ‘good refugee/bad refugee’ are connected in public discourse, policy and practice surrounding the refugee crisis in Europe and Australia. It will examine whether, and how, the public and political discourses on the refugee crisis, refugees (or forced migrants) are shaped by these binary oppositions, across different territorial contexts.

The working hypothesis of this project is that the binary oppositions of ‘good religion/bad religion’, ‘good Muslim/bad Muslim’, and ‘good refugee/bad refugee’ are key features of the discourses in both contexts and contribute to the construction of refugees and forced migrants as a security threat, necessitating a military security response, rather than a humanitarian response. There is a growing need for theoretical and practical reflection on the one hand, and a strong need for creating informed policy recommendations to prevent inhuman practices on the ground, inequality, violence, cultural polarizations and isolation, and dehumanization of refugees.

Aukje Muller

Never-End (Hi)story: Gregorio Lopez and his models

“No hay secreto, todo es claro, medio dia es para mi.”

(“There is no secret, all is clear, for me it is noon.”) - Gregorio Lopez [c.1542 – 1596].

In Losa, Francisco. Vida que el siervo de Dios Gregório Lopez hizo en algunos lugares de la Nueva España… Madrid : António del Ribero Rodriguez, Mercador de Libros, 1648

“He had a globe and a map made with his owne handes very truly and exactly, […]”

In Losa, Francisco. The life ofGregorieLopesthat great servant of God,natiueof Madrid, writtenin Spanish by Father Losa curate of theCathedrallof Mexico … Translated by Thomas White. Paris : [Widow of J. Blagaert], [1638]

![Gregorio Lopez [c.1542-1596]](/rcs/organization/images/l-nunes.jpg)

A man with an earth globe, a map and a bible. The legend of Gregorio Lopez was told in many ways from the 16th century to the present day. For diverse goals, within a medley of meanings and agendas: he was a “servant of God” (Losa), a “pre-quietista” (Molinos, Dudon, Martins), a “milenarist” and alumbrado (Milhou), an ascetic hermit (Huerga), a “failed” colonial saint (Rubial Garcia, Bilinkoff); in resume an original Spanish Catholic sample of the New World (Mexico)’s Church. By writing the historical biography of this 16th century man, I’ll try to understand how he became a model and whose model(s) he imitated and embraced.

After dissecting the body of knowledge built around him, and approaching it from different disciplines (philosophical, theological, anthropological, sociological, psychological), I’ll try to get to his own examples. History is like “police work” (Pimentel) and at the same time “it is the best novel ever” (Lourenço). My purpose then is to make a historical interpretation of Gregorio Lopez and his models: the ones he took and the ones he became. Through discourse analysis, symbolic anthropology, social network analysis, book history, I will try to interpret Gregorio’s world(s), knowledge(s), and life(s). Like for any other homo historicus, the time and place he was born and raised, but also the persons he imitated, studied, heard, saw and knew, made him the man he ended up to be.

Where does the “Once upon a time” starts in this story? A 16th century layman in the New Spain, carrying an Earth Globe, a Map and a Bible? An author that writes a Explicacíon del misterioso libro del Apocalypsis and a Tesoro de Medicinas? An Iberian man exploring the possibilities of new geographical, spiritual and cultural worlds?

A critical evaluation of the role of religion in theories of International Relations

In 2005 President Mahmoud Ahmadinedad of Iran closed a speech at the United Nations with a call for the ‘mighty Lord’ to ‘hasten the emergence’ of Imam Mahdi, a direct descendent of the Prophet Muhammed. Mahid, a redeemer of Islam, will return from hiding to rid the world of injustice. [1]

According to the Former Palestinian minister of Foreign Affairs Nabil Shaath in an interview with the BBC, Bush said during a Israeli-Palestinian summit that God told him: ‘George go and fight these terrorists in Afghanistan’, ‘George, go and end the tyranny in Iraq’ and ‘Go get the Palestinians their state and get the Israelis their security, and get peace in the Middle East.’ A spokesman for President Bush has said these claims were absurd: ‘He has never made such a comments.’ [2]

Does religion play a role in international politics? Yes, but the question is: did it always play a role and what kind of a role did it play? Did this role change over the years? Is religion really increasing or is it just manifesting itself differently at this moment? These questions are important for people that want to theorize on international relations.

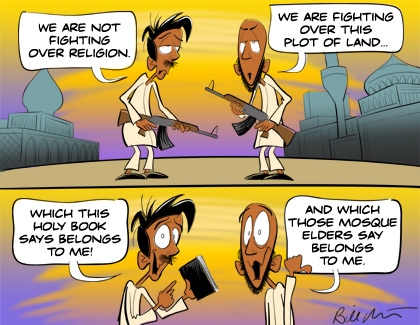

The role of religion in conflicts is nicely illustrated by this comic strip. It shows that religion is seldom the sole cause of a conflict. Religion is often used to raise the masses and unite people for a certain goals. In that case religion catalyzes the conflict. To clarify the role of religion in international relations I study the question: can religion help us to understand or explain international relations? In order to answer this question I start to analyze whether current theories of international relations deal with religion and how the possible absence of religion can be explained. I use this knowledge to evaluate current attempts to give religion a place in theorizing. The purpose of this research is to find out whether the theories that are dominant in the field of International Relations are still valid. If these theories are not valid anymore, I would like to indicate how a theory of international relations and religion should look like. In this way, I hope to serve the world of the second millennium with academic insights.

Contact Simon Polinder

[1] New York Times, 19th of June 2008, consulted at 8-09-2008

[2] Guardian, 7th of October 2005, consulted at 9-09-2008

| Last modified: | 27 March 2024 3.38 p.m. |